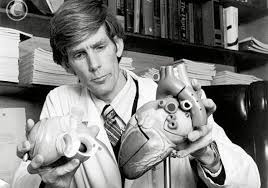

Sometime this year doctors at the University of Utah Hospital in Salt Lake City will implant an artificial heart in a human—and for the first time the chances for success are very high. If the atomic battery-powered heart does work, it will be the capstone of one of modern medicine’s most illustrious careers for Dr. Willem Kolff, 64, who directed the project. In 35 years of remarkable innovation, beginning with a machine that does the work of the human kidney, Kolff has pioneered in the field of artificial organs. And in just seven years as director of Utah’s Division of Artificial Organs, he has almost single handedly created the foremost research team of its kind in the world.

Kolff says the work at the school is aimed only at making life more bearable for the physically handicapped, but if TV’s artificial Six Million Dollar Man were ever to become a reality, doubtless it would be the work of the Utah group. In addition to an artificial heart that kept a calf alive for 94 days, the researchers have created artificial eyes—actually miniaturized television cameras implanted in the eye sockets—which transmit pictures to the brain. The “eyes” were implanted in a totally blind Vietnam veteran, who was able to perceive blurry shapes.

Kolff’s team is now working on an artificial ear and on limbs that will attach not only to the skeleton of the patient but also to his central nervous system. With such prostheses or artificial members, an amputee could recover both motor functions and a sense of touch.

As a young man in Holland, Kolff was repulsed by suffering and death, which he witnessed more frequently than most boys because his father was a physician. “The thought of having a career where I would have to watch people die troubled me,” he recalls, “so much so that I once seriously considered becoming a good zoo keeper.”

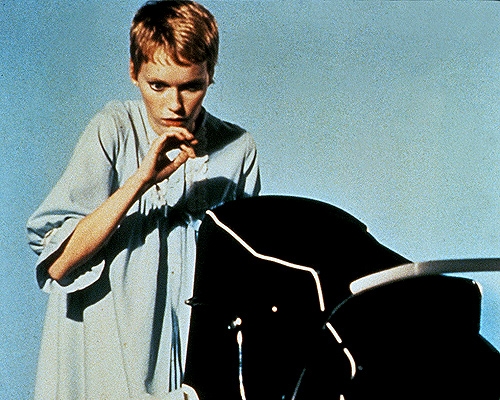

Nevertheless, his father’s intense dedication to the profession impressed young Willem, and in 1930, at the age of 19, he enrolled at the University of Leyden Medical School. During postgraduate work at the hospital of the University of Groningen, the 29-year-old doctor was given charge of four patients—one a young man of 22 who was dying slowly from kidney failure. “I had the awful task,” Kolff recalls, “of telling this sobbing peasant woman that her only son could not be saved. I thought if we could only remove some of the waste products from his blood he might survive and live a normal life.”

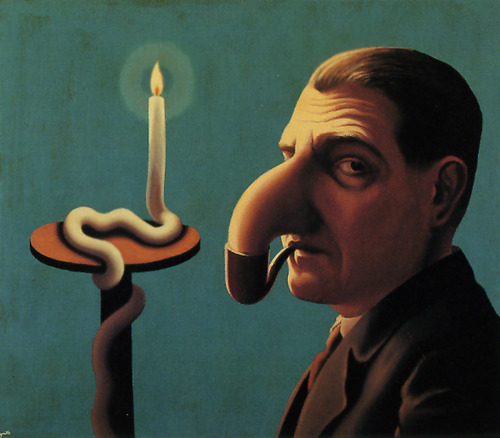

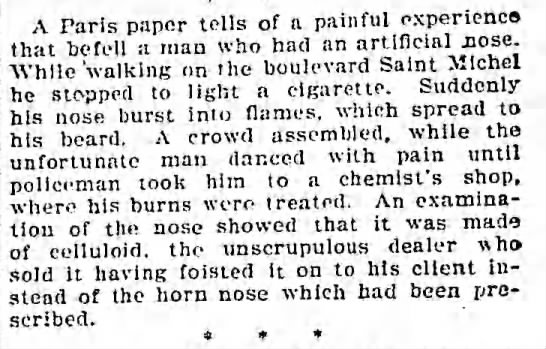

Kolff dug obsessively through medical libraries searching for a clue that might lead him to a method for cleansing blood, and he began laboratory experiments on the problem. He found that waste materials in the bloodstream, which are normally removed by the kidneys, would seep through extremely thin cellophane casings (such as those used to wrap sausage) when the casings were submerged in a saline bath. Blood cells would not, being too large to pass through the porous membrane.

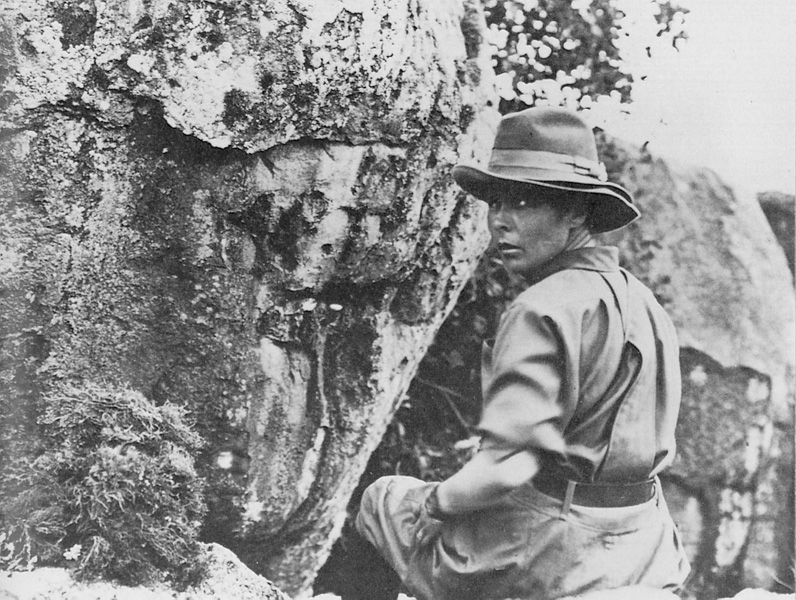

Kolff’s work in Groningen was interrupted by the Nazi invasion in 1940, and he removed to Kampen to continue it. In his laboratory there, he wrapped cellophane tubing around a horizontal drum, which had been partially immersed in saline solution. When the blood of the kidney patient passed through the tubing, as the drum rotated, the impurities percolated through the cellophane membrane while the purified blood could be returned to the patient’s system. Kolff had effectively built an artificial kidney.

His Rube Goldberg-looking dialysis machine alarmed many of Kolff’s conservative peers, and they were reluctant to refer their own failing-kidney patients to the brash young doctor. He was able to work only with patients thought to be terminally ill. Although most of the 16 of these showed marked improvement immediately after being hooked up to Kolff’s artificial kidney, all died. Then, finally, in 1944 the seventeenth patient, Sofia Schafstadt, survived.

While Kolff’s remarkable mechanical kidney did not arouse much interest in postwar Europe, physicians from the United States beat a path to his laboratory door. In 1950 he was invited to join the prestigious Cleveland Clinic, where he eventually became the scientific director of the artificial organs program.

“He was one of those men,” recalls Dr. Yukihiko Nosé, who replaced Kolff when he left for Utah, “who can completely overpower you in the beginning. He is a typical European, paternalistic and demanding. On their first day in the lab Kolff gave all new foreign doctors a three-page memo on how to survive in America. It told us how many times to bathe each week, what deodorant to use and how to dress. Until he believes in you, he expects everything to be done his way. He can be very difficult to work with at first.”

In Cleveland Kolff became something of a medical and social maverick. “They were all Republicans there. I was about the only Democrat,” he recalls laughing. “They were very suspicious of government grants—they thought if government money was withdrawn from a project, the clinic would be obliged to keep funding it.” Kolff was used to getting his own way and could be quite imaginative about it. He blithely circumvented the chain of command at the clinic whenever it served his purposes. “It seemed there was a constant state of siege between Kolff and the board of governors over which patients should be hooked onto the dialysis machine,” another former associate says. “Naturally the clinic wanted to limit the number of indigent patients. Kolff didn’t give a damn whether patients could pay or not—he thought rich and poor should be treated alike.” …

By 1967 Kolff had become increasingly impatient with the bureaucracy and politics at the Cleveland Clinic. In his 17 years there he had pressed the development of the heart-lung machine and the inter-aortic balloon pump, which had helped diminish the risk of heart surgery. But Kolff’s ways had offended some superiors, who had retaliated by clamping a tighter rein on his research projects. When Dr. Keith Reemtsma, now at Columbia, offered to create a division for Kolff at Utah, with improved funding and virtual autonomy, Kolff quickly accepted, even though the post paid only $26,000 a year—considerably less than what he earned in Cleveland. He is permitted to supplement his income as a consultant, but turns over most of the income to the university and charity.

At Utah Kolff remains an unorthodox operator—on occasion making appeals directly to the governor for support of his projects. So far no one seems to mind—least of all Governor Calvin Rampton. He is only too pleased at the publicity Kolff has brought the state, not to mention his growing, pollution-free small industry in artificial organs and spare mechanical parts.

Now Kolff’s department boasts more than 100 employees. A scientific Pied Piper, he collects machinists, veterinarians or chemists if he thinks they can help solve his problems. Distinctions between professional ranks and the skilled but less-educated staff members bore him. He is fond of saying, “I’ll take a good technician over a mediocre doctor any day.” The oftentimes dour Dutchman inspires fierce loyalty in his associates. Says one, “If a guy has a good idea, Kolff will go to the wall for him—he gives credit where credit is due.”

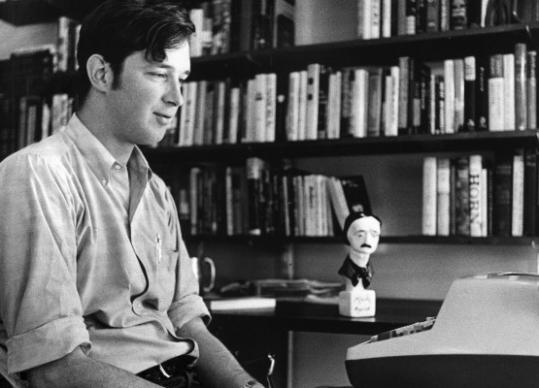

The designer of the artificial heart (which is made of silicone rubber) is a brilliant third-year medical student, Robert Jarvik, who seems destined for a career as remarkable as his chief’s. Recently, Levi Porter, a sophomore engineering student whose own defective kidney requires dialysis treatment, was instrumental in developing parts for a kidney machine small enough to be carried by the patient.

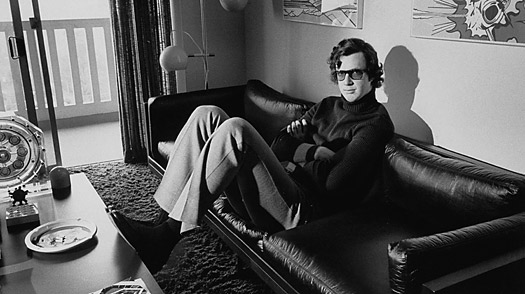

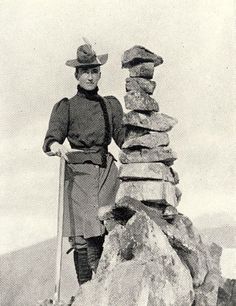

In stark contrast to the flamboyant life-styles of such other heart researchers as Christiaan Barnard and William DeBakey, Kolff leads an austere life outside the laboratory. A conservative dresser, preferring the same brown coat and striped tie, he spends most of his evenings at home with Janke, his wife of 37 years, sipping tea and gazing out at the Salt Lake Valley, which unfolds beneath the bay window in his living room. He has become a generous backer of the Utah Symphony Orchestra and holds season tickets for two of the best seats in the Salt Lake Tabernacle, where the orchestra performs. All of his five children—Jack, daughter Adriana, Albert, Kees, Therus—are grown now: three of his sons are doctors and one is an architect who designs medical facilities. The oldest, Jack, recently joined his father’s research team.•