_________________________

Question:

Hi Bob, Was it ever weird growing up in your home considering who your father was? I mean did a Penthouse Pet ever come to any of your birthday parties?

Also – I don’t know if you have any pull at Penthouse – but the Penthouse Comix publication was great and included many famous and great creators. Do you think there’d be any chance these stories could be reprinted?

Bob Guccione Jr.:

It wasn’t weird! And yes, Penthouse Pets did come to my birthday parties, but only when I was in my twenties!

The models in Penthouse were always off limits to my brothers and I (and, I assume, although I never thought about it before, my sisters…). That was smart of my father. By the time we’d worked out how to get around that, we were adults and had a better perspective of who these women were, and high respect for them, and our own lives. I was married at 24 to a woman who was a writer and worked in a store in London, England.

I have no pull at Penthouse (I don’t even know if it is still being published). But I agree with you about the comics! Some of them were brilliant, and some of the artists extraordinary.

_________________________

Question:

This may be random, but do you have a most memorable Beastie Boys story?

Bob Guccione Jr.

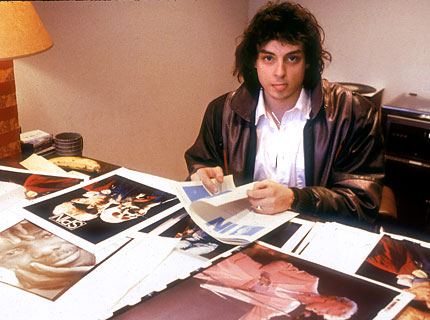

I do! When they were starting out they used to come up to our office and skateboard around the halls. I don’t think we had particularly good halls, I think we were just the only magazine that wouldn’t throw them out. Until we did! I eventually had to told them they couldn’t come around QUITE as much, on the grounds that my staff would all stop working, hang out with them and think they had the best job in the world because, apparently, when Beastie Boys turned up, they didn’t have to work.

I liked them a lot, they were really good people. Very sincere, very gentle and smart. And when I ran into them periodically after they had become huge stars, they always made time to talk.

_________________________

Question:

What was it like meeting Nirvana for the first time?

Bob Guccione Jr.

You know, as an aside, I ALMOST asked the Dalai Lama when I interviewed him what he thought of Nirvana, but I chickened out!

I first met Kurt and Courtney at Nirvana’s manager Danny Goldberg’s house in LA. He was quite, gentle, attentive, incredibly smart and you could feel very special. We hit it off right away and at the end of dinner, as we were all leaving, I told him how much I loved his music, and he said he always enjoyed reading my Topspin columns and had been reading them since he was 16. That was the first time it occurred to me that ARTISTS read me — I don’t know why it never occurred to me before, but it hadn’t.

I later met the whole band in Seattle and we hung out for a great evening that resulted in my sending Krist Novoselic to Croatia during the war in Yugoslavia, to cover the war for us. When Kurt found out, as Krist was leaving for the airport, he went apeshit and called me up from Brazil, where the band had just finished a tour, and screamed YOU’RE SENDING MY BASS PLAYER TO A FUCKING WAR ZONE! I said yes, we were, but I was sure he’d be alright… He was, and he did one of the best pieces we ever published (and which we’ll republish this year as part of the 30th anniversary).

_________________________

Question:

What’s your favorite/the most memorable story SPIN has ever done?

Bob Guccione Jr.

Wow, how long do you have? There are so many I love, so many I’m very proud of and a ton that are memorable.

I think I’m proudest of our coverage of AIDS actually, it changed the world’s perception of how much was actually, really known about the awful disease/collection of diseases. Our reporting cut through the (then) rampant hysteria and forced a lot of crap science and reporting into the light where it could be more soberly evaluated. We ended the death-bringing reliance on AZT for instance. Our reporting, over ten years, was often controversial and very often not generally agreed with, but as I always point out, we never once, in 10 years and 120 columns, had to print a correction. Our facts were airtight. Our opinions and conclusions were often debated and some still are, but we made people think differently, and most of the time NOT politically correctly. I have NO time for political correctness. It’s a cultural fraud. And AIDS science and media coverage was rife with it, which wasn’t doing anyone any good. Sober, real factual reporting did help people and I’ve met many over the years who have said reading SPIN saved their lives. One can barely hope to achieve more in one’s life than that.

I’m also proud of our Live Aid exposes that showed that the funding was going to buy weapons and fund deadly resettlement marches that killed 100,000 people. We reported that Geldof was repeatedly warned by the relief agencies in the field not to deal with the Ethiopian dictator Mengistu, but drunk with his own glory ignored everyone and gave all the money to this murderous thug. Our articles at first had us shunned by the music industry and the world’s media but I challenged hundreds of news organizations to report it for themselves, and when they did, they came to the same conclusion, and basically the resulting press halted the funding of this genocide. I’m very proud of that.

One of my other favorite stories was Tama Janowitz’s fictional accounting of giving Bruce Springsteen’s wife a lobotomy and replacing her, and Bruce doesn’t notice…. Look it up!•