From the November 5, 1926 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

Tags: Napoleon Bonaparte

10 search-engine keyphrases bringing traffic to Afflictor:

- garry willis 1974 all the president’s men

- philip zimbardo on donald trump

- trump “tapp my phones”

- trumpism social safety nets

- kremlin machismo

- thomas friedman sending us troops into syria

- yuval harari upgrading human beings

- tim harford technocrats

- father divine accentuate the positive

- we’re disgusting and barbaric

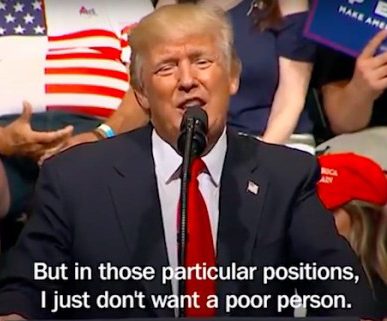

This week, Donald Trump decided to soften his image after publishing a tweet in which he encouraged violence against journalists.

Hey, Bones McCoy, I gotta seem like a nice guy. Let’s do a photo op at a petting zoo or a military cemetery or some crap like that.

• Thoughts on Garry Kasparov’s Deep Thinking from Nicholas Carr and me.

• Frank Rich compares the scandals of Nixon and Trump.

• Bruce Bartlett offers a searing takedown of GOP anti-intellectualism.

• In 1952, Wernher von Braun dreamed of launching gas chambers into space.

• Steven Levy quizzes Sebastian Thrun about the necessity of flying cars.

• Alexis Madrigal wonders about the wisdom of brain-to-brain interfaces.

• Jennifer Doudna addresses her key role in the “CRISPR Revolution.”

• Vice explores pet cloning, a very inexact and terribly expensive art.

• A brief note from 1928 about Rockefeller dimes.

• This week’s Afflictor keyphrase searches: Jack Dorsey, the Wonderland murders.

Muammar Gaddafi got exactly what he deserved, but so few do.

Muammar Gaddafi got exactly what he deserved, but so few do.

Wernher von Braun, Nazi scientist, warranted a hanging for his crimes against humanity, but he had a talent considered crucial during the early stages of the Cold War, so his past was whitewashed, and he was installed as the leader of NASA’s space program, ultimately becoming something of an American hero. So very, very unfair.

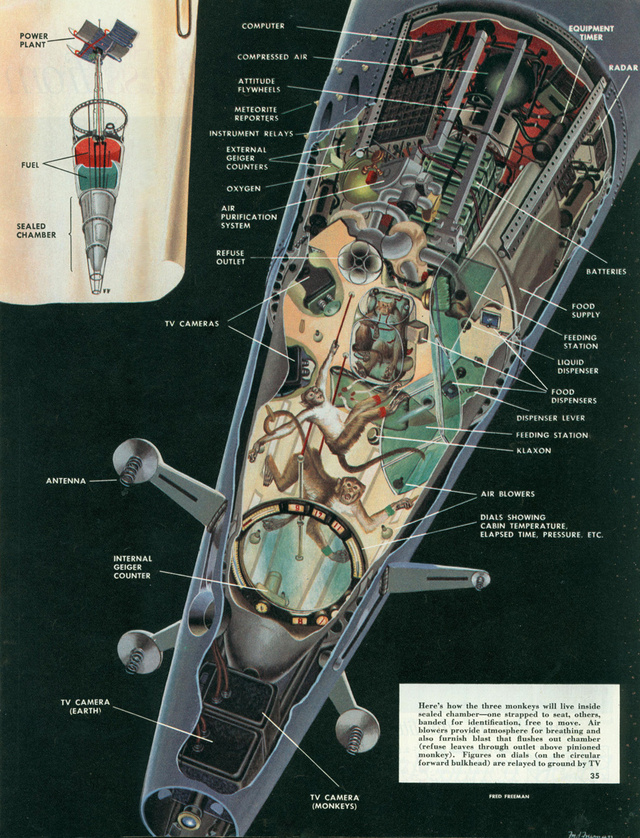

But his horrific past in Germany bled over into his new one in the U.S. in his early ’50s plan to send a “baby satellite” into space for two months with a crew of three rhesus monkeys. The mission completed, the rocket would burn up as it reentered the atmosphere. To save the primates from the pain of an inferno, Braun wanted to create an automatic switch which would gas the monkeys to death–yes, a gas chamber in space. “The monkeys will die instantly and painlessly,” he wrote in a 1952 Collier’s article he co-authored with Cornelius Ryan. It’s the damndest thing.

The article:

WE ARE at the threshold today of our first bold venture into space. Scientists and engineers working toward man’s exploration of the great new frontier know now that they are going to send aloft a robot laboratory as the first step—a baby space station which for 60 days will circle the earth at an altitude of 200 miles and a speed of 17,200 miles an hour, serving as scout for the human pioneers to follow.

We rocket engineers have learned a lot about space by shooting off the high-flying rockets now in existence—so much that right now we know how to build the rocket ships and the big space station we need to put man into space and keep him there comfortably. We know how to train space crews and how to protect them from the hazards which exist above our atmosphere. All that has been reported in previous issues of Collier’s.

But the rockets which have gathered our data have stayed in space for only a few minutes at a time. The baby satellite will give us 60 days; we’ll learn more in those two months than in 10 years of firing the present instrument rockets.

We can begin work on the new space vehicle immediately. The baby satellite will look like a 30-foot ice-cream cone, topped by a cross of curved mirrors which draw power from the sun. Its tapered casing will contain a complicated maze of measuring instruments, pressure gauges, thermometers, microphones and Geiger counters, all hooked up to a network of radio, radar and television transmitters which will keep watchers on earth informed about what’s going on inside it.

Speeding 30 times faster than today’s best jets, the little satellite will make one circuit around the earth every 91 minutes—nearly 16 round trips a day. At dawn and dusk it will be visible to the naked eye as a bright, unwinking star, reflecting the sun’s rays and traveling from horizon to horizon in about seven minutes. Ninety-one minutes later, it completes the circuit—but if you look for it in the same place, it won’t be there: it travels in a fixed orbit, while the earth, rotating on its own axis, moves under it. An hour and a half from the time you first sighted the speeding robot, it will pass over the earth hundreds of miles to the west. The cone will never be visible in the dark of night, because it will be in the shadow of the earth.

If you live in Philadelphia, one morning you may see the satellite overhead just before sunup, moving on a southeasterly course. Ninety-one minutes later, as dawn breaks over Wichita, Kansas, people there will see it, and after another hour and a half it will be visible over Los Angeles—again, just before the break of dawn.

That evening, Philadelphians—and the people of Wichita and Los Angeles—will see the speeding satellite again, this time traveling in a northeasterly direction. The following morning, it will be in sight again over the same cities, at about the same time, a little farther to the west.

After about ten days, it will no longer appear over those three cities, but will be visible over other areas. Thus, from any one site, it will be seen on successive occasions for about 20 days before disappearing below the western horizon. In another month or so, it will show up again in the east. And while you’re gazing at the little satellite, it will be peering steadily back, through a television camera in its pointed nose. The camera will give official viewers in stations scattered around the globe the first real panoramic picture of our world—a breath-taking view of the land masses, oceans and cities as seen from 200 miles up. More than likely, commercial TV stations will pick up the broadcasts and relay them to your home.

Three more cameras, located inside the cone, will transmit equally exciting pictures: the first sustained view of life in space.

Three rhesus monkeys—rhesus, because that species is small and highly intelligent—will live aboard the satellite in air-conditioned comfort, feeding from automatic food dispensers. Every move they make will be watched, through television, by the observers on earth.

As fast as the robot’s recording instruments gather information, it will be flashed to the ground by the same method used now in rocket-flight experiments. The method is called telemetering, and it works this way: as many as 50 reporting devices are hooked to a single transmitter which sends out a jumble of tonal waves. A receiver on earth picks up the tangled signals, and a decoding machine unscrambles the tones and prints the information automatically on long strips of paper, as a series of spidery wavelike lines. Each line represents the findings of a particular instrument—cabin temperature, air pressure and so on. Together, they’ll provide a complete story of the happenings inside and outside the baby space station.

What kind of scientific data do we hope to get? Confirmation of all space research to date and, most important, new information on weightlessness, cosmic radiation and meteoric dust.

At a high enough speed and a certain altitude, an object will travel in an orbit around the earth. It— and everything in it—will be weightless. Space scientists and engineers know that man can adjust to weightlessness, because pilots have simulated the condition briefly by flying a jet plane in a rollercoaster arc. But will sustained weightlessness raise problems we haven’t foreseen? We must find out—and the monkeys on the satellite will tell us.

The monkeys will live in two chambers of the animal compartment. In the smaller section, one of the creatures will lie strapped to a seat throughout the two-month test. His hands and head will be free, so he can feed himself, but his body will be bound and covered with a jacket to keep him from freeing himself or from tampering with the measuring instruments taped painlessly to his body. The delicate recording devices will provide vital information—body temperature, breathing cycle, pulse rate, heartbeat, blood pressure and so forth.

The other two monkeys, separated from their pinioned companion so they won’t turn him loose, will move about freely in the larger section. During the flight from earth, these two monkeys will be strapped to shock-absorbing rubber couches, under a mild anesthetic to spare them the discomfort of the acceleration pressure. By the time the anesthetic wears off, the robot will have settled in its circular path about the earth, and a simple timing device will release the two monkeys. Suddenly they’ll float weightless, inside the cabin.

What will they do? Succumb to fright? Perhaps cower in a corner for two months and slowly starve to death? I don’t think so. Chances are they’ll adjust quickly to their new condition. We’ll make it easier for them to get around by providing leather handholds along the walls, like subway straps, and by stringing a rope across the chamber.

There’s another problem for the three animals: to survive the 60 days they must eat and drink.

They’ll prepare to cope with that problem on the ground. For months before they take off, the two unbound monkeys will live in a replica of the compartment they’ll occupy in space, learning to operate food and liquid dispensers. In space, each of the two free animals will have his own feeding station. At specific intervals a klaxon horn will sound; the monkeys will respond by rushing to the feeding stations as they’ve been trained to do. Their movement will break an electric-eye beam, and clear plastic doors will snap shut behind them, sealing them off from their living quarters. Then, while they’re eating, an air blower will flush out the living compartment—both for sanitary reasons and to keep weightless refuse from blocking the television lenses. The plastic doors will spring open again when the housecleaning is finished.

The monkeys will drink by sucking plastic bottles. Liquid left free, without gravity to keep it in place, would hang in globules. To get solid food, each of the monkeys—again responding to their training—will press a lever on a dispenser much like a candy or cigarette machine. The lever will open a door, enabling the animals to reach in for their food. They’ll get about half a pound of food a day—a biscuit made of wheat, soybean meal and bone meal, enriched with vitamins. The immobilized monkey will have the same food; his dispensers will be within easy reach.

For the two free monkeys, it will be a somewhat complicated life. The way they react to their ground training under the new conditions posed by lack of gravity will provide invaluable information on how weightlessness will affect them.

While the monkeys are providing physiologists with information on weightlessness, physicists will be learning more about cosmic rays, invisible high-speed atomic particles which act like deep penetrating X rays and were once feared as the major hazard of space flight. Theoretically, in large enough doses cosmic rays could conceivably cause deep burns, damage the eyes, produce malignant growths and even upset the normal hereditary processes. They don’t do much damage to us on earth because the atmosphere dissipates their full strength, but before much was known about the rays people worried about the dangers they might pose to man in space. From recent experiments scientists now know that the risk was mostly exaggerated—that even beyond the atmosphere a human can tolerate the rays for long periods without ill effects. Still, the best figures available have been obtained by high-altitude instrument rocket flights which were too brief to be conclusive. These spot checks must be augmented by a prolonged study, and the baby space station will make that possible.

The concentration of cosmic rays over the earth varies, being greatest over the north and south magnetic poles. The baby space station will follow a circular path that will carry it close to both poles within every hour and a half, so it can determine if cosmic-ray concentration varies that high up.

Geiger counters inside and outside the robot will measure the number of cosmic particle hits. The telemetering apparatus will signal the information to the ground—and for the first time physicists will have an accurate indication of the cosmic-ray concentration in space, above all parts of the globe.

Besides cosmic rays, the baby satellite will be hit by high-speed space bullets—tiny meteors, most of them smaller than a grain of sand, whizzing through space faster than 1,000 miles a minute.

When men enter space, they’ll be protected against these pellets. Their rockets, the big space station, even their space suits, will have an outer skin called a meteor bumper, which will shatter the lightning-fast missiles on impact. But how many grainiike meteors must the bumpers absorb every 24 hours? That’s what we space researchers want to know. So dime-sized microphones will be scattered over the robot’s outer skin to record the number and location of the impacts as they occur.

In the process of unmasking the secrets of space, the baby satellite also will unravel a few riddles of our own earth.

For example, there are numerous islands whose precise position in the oceans has never been accurately established because there is no nearby land to use as a reference point. Some of them—one is Bouvet Island, lying south of the Cape of Good Hope—have been the subject of international disputes which could be quickly settled by fixing the islands’ positions. By tracking the baby space station as it passes over these islands, we’ll accurately pinpoint their locations for the first time.

The satellite will be even more important to meteorologists. The men who study the weather would like to know how much of the earth is covered with cloud in any given period. The robot’s television camera will give them a clue—a start toward sketching in a comprehensive picture of the world’s weather. Moreover, by studying the pattern of cloud movement, particularly over oceans, they may learn how to predict weather fronts with precision months in advance. Most of the weather research must await construction of a man-carrying space station, but the baby satellite will show what’s needed.

To collect this information, of course, we must first establish the little robot in its 200-mile orbit. All the knowledge needed for its construction and operation is already available to experts in the fields of rocketry, television and telemetering.

Before take-off, the satellite vehicle will resemble one of today’s high-altitude rockets, except that it will be about three times as big—150 feet tall, and 30 feet wide at the base. After take-off it will become progressively smaller, because it actually will consist of three rockets—or stages—one atop another, two of which will be cast away after delivering their full thrust. The vehicle will take off vertically and then tilt into a shallow path nearly parallel to the earth. Its course will be over water at first, so the first two stages won’t fall on anyone after they’re dropped, a few minutes after take-off.

When the third stage of the vehicle reaches an altitude of 60 miles and a speed of 17,700 miles an hour, the final bank of motors will shut off automatically. The conical nose section will coast unpowered to the 200-mile orbit, which it will reach at a speed of 17,100 miles an hour, 44 minutes later. The entire flight will take 48 1/2 minutes.

After the satellite reaches its orbit, the automatic pilot will switch on the motors once again to boost the velocity to 17,200 miles an hour—the speed required to balance the earth’s gravity at that altitude. Now the rocket becomes a satellite; it needs no more power but will travel steadily around the earth like a small moon for 60 days, until the slight air drag present at the 200-mile altitude slows it enough to drop.

Once the satellite enters its orbit, gyroscopically controlled flywheels cartwheel the nose until it points toward the earth. At the same time, five little antennas spring out from the cone’s sides and a small explosive charge blasts off the nose cap which has guarded the TV lens during the ascent.

Finally, the satellite’s power plant—a system of mirrors which catch the sun’s rays and turn solar heat into electrical energy—rises into place at the broad end of the cone. A battery-operated electric timer starts a hydraulic pump, which pushes out a telescopic rod. At the end of the rod are the three curved mirrors. When the rod is fully extended, the mirrors unfold, side by side, and from the ends of the central mirror two extensions slip out. Mercury-filled pipes run along the five polished plates; the heated mercury will operate generators providing 12 kilowatts of power. Batteries will take over the power functions while the satellite is passing through the shadow of the earth.

With the power plant in operation, the baby space station buckles down to its 60-day assignment as man’s first listening post in space.

At strategic points over the earth’s surface, 20 or more receiving stations, most of them set up in big trailers, will track the robot by radar as it passes overhead, and record the television and telemetering broadcasts on tape and film. Because the satellite’s radio waves travel in a straight line, the trailers can pick up broadcasts for just a few minutes at a time—only while the robot remains in sight as it zooms from horizon to horizon.

As the satellite passes out of range, the recorded data will be sent to a central station in the United States—some of it transmitted by radio, the rest shipped by plane. There, the information will be evaluated and integrated from day to day.

The monitoring posts will be set up inside the Arctic and Antarctic Circles and at points near the equator. In the polar areas, stations could be at Alaska, southern Greenland and Iceland; and in the south, Shetland Islands, Campbell Island and South Georgia Island. In the Pacific, possible sites are Baker Island, Christmas Island, Hawaii and the Galapagos Islands.

The remaining monitors may be located in Puerto Rico, Bermuda, St. Helena, Liberia, South-West Africa, Ethiopia, Maldive Islands, the Malay Peninsula, the Philippines, northern Australia and New Zealand. These points, all in friendly territory, would form a chain around the earth, catching the satellite’s broadcasts at least once a day.

The monitor stations will be fairly costly, but they’ll come in handy again later, when man is ready to launch the first crew-operated rocket ships for development of a big-manned space station, 1,075 miles from the earth.

The cost of the baby satellite project will be absorbed into the four-billion-dollar 10-year program to establish the bigger satellite. We scientists can have the baby rocket within five to seven years if we begin work now. Five years later, we could have the manned space station.

One of the monitoring posts will view the last moments of the baby space station. As the weeks pass, the satellite, dragging against the thin air, will drop lower and lower in its orbit. When it descends into fairly dense air, its skin will be heated by friction, causing the temperature to rise within the animal compartments. At last, a thermostat will set off an electric relay which triggers a capsule containing a quick-acting lethal gas. The monkeys will die instantly and painlessly. Soon afterward, the telemetering equipment will go silent, as the rush of air rips away the solar mirrors which provide power, and the baby space station will begin to glow cherry red. Then suddenly the satellite will disappear in a long white streak of brilliant light—marking the spectacular finish of man’s first step in the conquest of space.•

Can’t name a thinker from the second half of the 20th century who was more right about the seismic changes that were to come than Marshall McLuhan. Not Andy Warhol or Jane Jacobs or George Carlin or Malcolm X or anyone. I wonder if he doubted all he’d said when he was cast from the zeitgeist and accused of being a mountebank as his celebrity faded. Likely he still knew he was largely correct.

A McLuhan quote rebounding around Twitter today: “World War III [will be] a guerrilla information war with no division between military & civilian participation.” That line, from 1970’s Culture Is Our Business, sums up the destabilized, decentralized state of life in 2017 in the wake of a Presidential election fought by bot armies. There was a time not too long ago, during the Arab Spring, when social media was greeted as a liberator, but now we have direct evidence all that connectedness has delivered a permanent state of anarchy. The term chaos agent, long used to describe individuals, is today an apt descriptor for the most popular medium.

What the theorist feared most of all was the Global Village, the reality that we were all becoming one tribe because of satellites and other communication enablers. It may have seemed especially misanthropic during the decade that gave us the Summer of Love, but it was really just a practical concern. And now that we’re a computerized society, all living in the same room, the technologies will endeavor to bring us even closer–inside of each other’s heads in unprecedented ways.

In “DARPA’s Ex-Leader’s Speculative Dream of Mind-Melding Empathy,” Alexis Madrigal of the Atlantic writes of Arati Prabhakar’s Aspen Ideas Festival speech about a radical vision of increasing connectedness. The journalist, very appropriately, believes it may create a nightmare. An excerpt:

Then she delivered the true Utopian dream:

“Imagine if we could connect among ourselves in new and deeper ways and imagine if those connections happened in a way that gave us so much empathy and understanding of each other that we could put our minds together, literally, to take on some of the world’s hardest problems.”

She did not expound on the image, but one imagines she’s thinking about a kind of direct brain-to-brain interface.

DARPA has, after all, invested a lot in direct electronic brain interfaces. In one research program, they’re working on “intuitive” neural interfaces for controlling prosthetic limbs. In another, they’re creating “an implantable neural interface able to provide advanced signal resolution and data-transfer bandwidth between the brain and electronics.” The goal there is to create a translator between “the electrochemical language used by neurons in the brain and the ones and zeroes that constitute the language of information technology.”

And once you’ve got intuitive neural controls and a translator that lets you send brain signals into computers and back again, it does not seem an incredible leap to hook two (or … a million?) humans up together.

“If we could get to that future, we would look back at today’s reality and it would look like black-and-white,” Prabhakar said. “It would look like flatland.”•

Tags: Alexis Madrigal

Loved the long centerpiece of Garry Kasparov’s Deep Thinking, in which perhaps the greatest chess champion of all recreates his epic 1996 and 1997 matches with Deep Blue, the IBM program that ultimately toppled him–and by extension, us. The barrage of machinations employed by the computer company are fascinating and worthy of Cold War spooks, which makes this section read like an espionage thriller married to insightful sportswriting.

The rest of the book is an interesting meditation on the intelligent machines that increasingly surround us, consume us, though Kasparov’s argument that we should stop worrying and learn to love the “bomb” doesn’t completely convince because he gives short shrift to the many potential pitfalls.

A few random thoughts.

· · ·

While Steven Levy’s cover line, “The Brain’s Last Stand,” was a great way to sell his Newsweek article that previewed the second match, it also was a simplification of a complex point. There’s no one instant when intelligent machines absolutely surpass us, no Turing Test or ego-deflating checkmate, Watson win or Singularity moment can do the trick. It’s a gradual process. Apollo 11’s success, IBM’s victory and Deep Learning’s mysterious prowess are all part of an eerie landscape in which there is no Main Street. The landmarks are scattered and continually being built.

Kasparov makes this point himself in depicting the titanic contests as great theater and personally taxing but almost completely beside the point. He knew that even if he triumphed in ’97, the machines would soon far surpass their carbon-based competitors. Kasparov might have staved off IBM long enough to avoid being the one to “earn” the John Henry tag, but soon enough the number one player in the world, whoever that may have been, was going down.

· · ·

Early in the volume, on page 47, Kasparov tries to relate to people whose livelihoods, and sometimes communities, have been devastated by technological innovation (in tandem with globalization), arguing that “few people in the world know better than I do what it’s like to have your life’s work threatened by a machine.” Hmm, it would seem that a brilliant, world-famous, fairly well-off guy in his thirties would be fine even if he was shoved aside by AI, but maybe he was truly terrified like those who hope the plant in Ohio doesn’t kick them to the curb.

Later that very same page, however, Kasparov writes: “Nor did I believe the apocalyptic predictions about what might happen if I lost a match to a machine. I was always optimistic about the future of chess in a digital age.” Whew, crisis averted!

The author sees a progression in which for a period of indeterminate length humans and machines collaborate on many forms of work until our silicon sisters take full control of these processes and we move on to other more important matters. That’s probably correct, but it’s not so likely to unfold as neatly off the page, especially since industries can rise and fall far more quickly during a technological boom.

Think how rapidly CDs went from the most successful format in music-business history to being almost worthless when the sounds disappeared into the 0s and 1s. Consider that Blockbuster and Polaroid and Fotomat went under during just the first wave of the Internet. Even if the aggregate job numbers don’t end up diminished, discomfiting displacement may become a permanent feature of life, as we’re all engaged in a never-ending game of musical chairs. That can’t be healthy for a society. From an economic standpoint, you wouldn’t want to be a nation that misses out on the Digital Age, but things could, and probably will, get messy. Some will be seated comfortably and many will fall to the floor.

· · ·

I’m working from memory, but I think Kasparov dedicates about three pages to the thorny problems of surveillance, privacy, hacking, etc. That’s not nearly adequate. As physical objects from cars to refrigerators to personal assistants are computerized and seamlessly integrated into our lives, these issues will become enormous. Actually, they already are. The author believes these complications to be fixable bugs.

AMAZON, 1998: hello we sell books but online

AMAZON, 2023: please return to your Primehouse for your nightly Primemeal, valued Primecitizen

— KRANG T. NELSON (@KrangTNelson) June 16, 2017

The main problem with his reasoning is it assumes there must be reasonable answers to vexing Digital Era questions. That’s not necessarily so. Perhaps there’s no taming the anarchy of a “smart” world that’s super-connected. Certainly Kasparov’s arch-nemesis Vladimir Putin wouldn’t have been able to influence the Brexit and U.S. Presidential votes without linked computers, those chaos agents. Mayhem may be baked so deeply into the new tools that the havoc is inseparable–and insuperable. It could even be that a highly technological society, a deeply connected and heavily sensored one, ultimately destroys itself. I don’t believe that scenario plausible, but it’s irresponsible to not consider it possible.

Those challenges are just the ones we’re aware of. Nobody knew a century ago that the internal combustion engine would soon create an existential threat. Tomorrow’s tools will be far more powerful and so probably will be their unintended consequences.

· · ·

In one passage, Kasparov asserts that his quote from 1989 in which he predicted AI would become world champion before a woman did wasn’t sexist. Well, perhaps that’s so, but the suspicion seems more understandable if you know the context the author has omitted. If anyone in 1989 suspected Kasparov was deeply sexist that’s because in 1989 Kasparov was deeply sexist.

From a Playboy Interview that year:

Playboy:

How about women chess players?

Garry Kasparov:

Well, in the past, I have said that there is real chess and women’s chess. Some people don’t like to hear this, but chess does not fit women properly. It’s a fight, you know? A big fight. It’s not for women. Sorry. She’s helpless if she has men’s opposition. I think this is very simple logic. It’s the logic of a fighter, a professional fighter. Women are weaker fighters.

There is also the aspect of creativity in chess. You have to create new ideas. That’s quite difficult, too. Chess is the combination of sport, art and science. In all these fields, you can see men’s superiority. Just compare the sexes in literature, in music or in art. The result is, you know, obvious. Probably the answer is in the genes.

Playboy:

Do you realize that you’re expressing a sexist point of view, and that Western women will be enraged by it?

Garry Kasparov:

Yes, but I’m not concerned. I’m sure that women can do many things better than men in many fields. I think it’s wrong to want to be compared all the time, to want to be equal in everything. Men and women are different.•

Two daughters and two decades later, Kasparov was far more enlightened when questioned by the same magazine:

Playboy:

Why are there relatively few women chess players?

Garry Kasparov:

Tradition. How many women composers are there? Architects? Things are changing in this. We have Judit Polgar, who proved a woman can make the top 10, though she didn’t come even close to number one.•

Okay, sexism would have been a more apt word choice than tradition, but I don’t blame Kasparov from wanting to recoil from his earlier misogyny, seeing how he’s apparently grown past it. But disappearing this failing removes an important lesson: Humans, like intelligent machines, can learn and grow in surprising ways.

· · ·

In “A Brutal Intelligence: AI, Chess, and the Human Mind,” Nicholas Carr reviews Kasparov’s title for the Los Angeles Review of Books, making interesting observations about the limits of blunt-force computing and the very nature of chess. Carr notes that our type of thinking will likely be beyond the reach of computers into the long-term future but worries that “brutally efficient calculations” will become more valued than the inexpressible nuances of human thought. An excerpt:

The history of computer chess is the history of artificial intelligence. After their disappointments in trying to reverse-engineer the brain, computer scientists narrowed their sights. Abandoning their pursuit of human-like intelligence, they began to concentrate on accomplishing sophisticated, but limited, analytical tasks by capitalizing on the inhuman speed of the modern computer’s calculations. This less ambitious but more pragmatic approach has paid off in areas ranging from medical diagnosis to self-driving cars. Computers are replicating the results of human thought without replicating thought itself. If in the 1950s and 1960s the emphasis in the phrase “artificial intelligence” fell heavily on the word “intelligence,” today it falls with even greater weight on the word “artificial.”

Particularly fruitful has been the deployment of search algorithms similar to those that powered Deep Blue. If a machine can search billions of options in a matter of milliseconds, ranking each according to how well it fulfills some specified goal, then it can outperform experts in a lot of problem-solving tasks without having to match their experience or insight. More recently, AI programmers have added another brute-force technique to their repertoire: machine learning. In simple terms, machine learning is a statistical method for discovering correlations in past events that can then be used to make predictions about future events. Rather than giving a computer a set of instructions to follow, a programmer feeds the computer many examples of a phenomenon and from those examples the machine deciphers relationships among variables. Whereas most software programs apply rules to data, machine-learning algorithms do the reverse: they distill rules from data, and then apply those rules to make judgments about new situations.

In modern translation software, for example, a computer scans many millions of translated texts to learn associations between phrases in different languages. Using these correspondences, it can then piece together translations of new strings of text. The computer doesn’t require any understanding of grammar or meaning; it just regurgitates words in whatever combination it calculates has the highest odds of being accurate. The result lacks the style and nuance of a skilled translator’s work but has considerable utility nonetheless. Although machine-learning algorithms have been around a long time, they require a vast number of examples to work reliably, which only became possible with the explosion of online data. Kasparov quotes an engineer from Google’s popular translation program: “When you go from 10,000 training examples to 10 billion training examples, it all starts to work. Data trumps everything.”

The pragmatic turn in AI research is producing many such breakthroughs, but this shift also highlights the limitations of artificial intelligence. Through brute-force data processing, computers can churn out answers to well-defined questions and forecast how complex events may play out, but they lack the understanding, imagination, and common sense to do what human minds do naturally: turn information into knowledge, think conceptually and metaphorically, and negotiate the world’s flux and uncertainty without a script. Machines remain machines.

That fact hasn’t blunted the public’s enthusiasm for AI fantasies.•

Tags: Garry Kasparov, Nicholas Carr

Have you ever had a dream that you’re walking with a deceased relative, trying to hold them steady because they’re unstable, and you can’t explain basic things to them because they are themselves but not themselves, awake but asleep, and they’re upset because they can’t understand and you’re upset because they’re upset?

· · ·

Our personalities and interests develop differently if we grow up in NYC or LA or Reykjavik because our surroundings inform us. Speaking one language or another or existing within this hierarchy or that one also leave a mark. Traumas that occur (or don’t occur) cut deeper still. A Scientific American article from last year summed it up this way: “The idea of cloning a deceased loved one—human or pet—has fallen out of favor in part because of the recognition that environment affects behavior. The genetics might be the same but would a clone still be the same lovable individual?”

· · ·

When futurists suggest human brains will soon be “uploaded” to computers, they assume consciousness isn’t at all shaped by the body and won’t be by whatever new containers hold “us.” That seems a huge oversight. The same goes for those who chose to cryogenically preserve their heads in the hope of someday being awakened or restored.

· · ·

In Luke Winkie’s Vice article “In the Future, You Will Have the Same Pet Your Entire Life,” the writer looks at those who just can’t let go of their four-legged friends, sometimes selling their assets to pay the $50,000 to $100,000 required to create a very imperfect “copy.” An excerpt:

Its cloning process is more straightforward than you might think. A Sooam clerk will meet you at the Seoul airport and retrieve a fingernail-length biopsy of your dead pet’s flesh. A donor dog or cat is selected from the company’s kennel. Their eggs are flushed out, gutted of their genetic information, and fused with DNA harvested from the biopsy. If the process works, the retrofitted egg is inserted into a surrogate mother. “Until the point where they actually meet the dog, [the customer] is in a very happy disbelief,” says [Jae Woong] Wang. “But once we deliver the dog, they usually burst into tears.”

The jury is still out on what a clone actually is. It’s a conundrum that’s raged ever since Dolly, the famous duplicated sheep, was brought into the world in 1996. Genetically, they’ll be a mirror image of the source animal, an asexually wrought son or daughter built in the flash of nuclear transfer. But will the clone share the same emotions or personality tics? That’s difficult to say. Research on cloned cows and pigs has shown distinct differences in personality—and even looks—from the animal of origin to its clone.

As such, New York Magazine‘s Science of Us blog called pet cloning “a laughable, extravagant waste of money,” when news broke last year that media tycoon Barry Diller and fashion mogul Diane von Furstenberg had their Jack Russell terrier cloned, even though the wealthy power couple seemed pleased with the two puppies they got as a result. And, in an interview with Scientific American, stem cell biologist Robin Lovell-Badge maintained that cloning a pet was, flatly, “stupid.” “You’re never gonna get Tibble back, or whatever,” he added.

But companies like Sooam deal in love—or more specifically, the faint chance that you might love again.•

Tags: Jae Woong Wang, Luke Winkie

Sebastian Thrun is a brilliant guy who was positioned at the starting line of the recent boom in driverless technology, but he’s no stranger to irrational exuberance. A couple years ago, the Udacity founder earnestly announced that “if I could double the world’s GDP, it would be very gratifying to me.” Yes, that would be nice.

The computer scientist and entrepreneur is now employed as CEO of Larry Page’s Kitty Hawk, engaged in trying to perfect the flying car, a vehicle of retrofuture dreams that seems exceedingly unnecessary. Wouldn’t it be far better for society if he and others like him were engaged in innovation aimed at more practical public transportation solutions for the masses? The thing about childhood dreams is that most of them are childish.

Steven Levy held roughly the same view last month when he sat down to interview Thrun for Backchannel (now housed at Wired). The opening:

Steven Levy:

Why do we need flying cars?

Sebastian Thrun:

It is a childhood dream. Flying is just such a magical thing to do. Making personalized flight available to everybody really opens up a set of new experiences. But in the long term there’s a practicality to the idea of a flying vehicle that takes off vertically like a helicopter, is very quiet, and can serve short range transportation. The ground is getting more and more congested. In the US, road usage increases by about three percent every year. But we don’t build any roads. And countries like China that very recently witnessed an explosion of automotive ownership are suffering tremendously from unbelievable traffic jams. While the ground infrastructure of roads is one-dimensional, the sky is three-dimensional, and it is much, much larger.

Steven Levy:

But it you build flying cars, won’t the air be just as congested?

Sebastian Thrun:

The nice thing about the air is there is more of it. You could have virtual highways in the sky and stack them vertically. So you never have a traffic intersection or similar.

Steven Levy:

But highways have lanes. You can’t have dotted lines in the sky.

Sebastian Thrun:

Yes, you can, it turns out. Thanks to the US government we have the Global Positioning System that gives us precision location information. We can paint virtual highways into the sky. We are actually doing this today. When you look at the way planes fly, they use equipment that effectively constructs highways in the sky.

Steven Levy:

Still, the number of planes is tiny compared to cars, which you want to put in the air. Plus, everybody is buying drones. If you folks get your way, the sky is going to be completely full.

Sebastian Thrun:

Every idea put to the extreme sounds odd.•

Tags: Sebastian Thrun, Steven Levy

As I’ve written before, plenty of people will rush to have “CRISPR babies” and be willing recipients of makeovers that extend far further than skin-deep. Botox and fillers and cosmetic surgery apps are just a dress rehearsal for what’s to come, and it will arrive, whether China or Europe or the U.S. first begins experimenting in earnest with gene modification. There are currently many unintended consequences attending the process, but the “games” will eventually begin.

In regards to the proliferation of plastic surgery, here’s an excerpt from a BBC piece by Dominic Hughes about children being targeted with propaganda:

Prof. Jeanette Edwards, from the University of Manchester, who chaired the council’s inquiry into ethical issues surrounding cosmetic procedures, said some of the evidence around games aimed at younger children had surprised the panel.

“We’ve been shocked by some of the evidence we’ve seen, including make-over apps and cosmetic surgery ‘games’ that target girls as young as nine.

“There is a daily bombardment from advertising and through social media channels like Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat that relentlessly promote unrealistic and often discriminatory messages on how people, especially girls and women, ‘should’ look.”•

The next phase, the bold move toward “designer babies,” is addressed in Ed Yong’s smart Atlantic article about scientist Jennifer Doudna trying to reckon with her prominent role in the “CRISPR Revolution.” The opening:

Jennifer Doudna remembers a moment when she realized how important CRIPSR—the gene-editing technique that she co-discovered—was going to be. It was in 2014, and a Silicon Valley entrepreneur had contacted Sam Sternberg, a biochemist who was then working in Doudna’s lab. Sternberg met with the entrepreneur in a Berkeley cafe, and she told him, with what he later described to Doudna as “a very bright look in her eye that was also a little scary,” that she wanted to start applying CRISPR to humans. She wanted to be the mother of the first baby whose genome had been edited with the technique. And she wanted to establish a business that would offer a menu of such edits to parents.

Nothing of the kind could currently happen in the U.S., where editing the genomes of human embryos is still verboten. But the entrepreneur apparently had connections that would allow her to offer such services in other countries. “That’s a true story,” Doudna told a crowd at the Aspen Ideas Festival, which is co-hosted by the Aspen Institute and The Atlantic. “That blew my mind. It was a heads-up that people were already thinking about this—that at some point, someone might announce that they had the first CRISPR baby.”

The possibility had always been there. Bacteria have been using CRISPR for billions of years to slice apart the genetic material of viruses that invade their cells. In 2012, Doudna and others showed how this system could be used to deliberately engineer the genomes of bacteria, cutting their DNA with exceptional precision. In quick succession, researchers found that they could do the same in mammalian cells, mice, plants, and—in early 2014—monkeys. “I had all of this at the back of my mind,” Doudna told me after her panel. But Sternberg’s story about his meeting “was the moment where I said I needed to get involved in this conversation. I’m not going to feel good about myself if I don’t talk about it publicly.”

That has not been an easy journey. Doudna built her career on molecules and microbes. As few as five years ago, she was, by her own admission, working head-down in an ivory tower, with no plans of milking practical applications from her discoveries, and little engagement with the broader social impact of her work.

But CRISPR forcefully yanked Doudna out of that closeted environment, and dumped her into the midst of intense ethical debates about whether it’s ever okay to change the DNA of human embryos, whether eradicating mosquitoes is a good idea, and whether “fixing” the genes behind inherited diseases is a blow to disabled communities.•

Tags: Dominic Hughes, Ed Yong, Jeanette Edwards, Jennifer Doudna

Trump will eventually be flushed down the vortex along with other waste products swirling around him, I’m fairly certain at this point, but as an amateur student of human psychology I’d be fascinated to know if he’s fully wrapped his declining brain around this scenario. Is it within his mental powers to grasp that some combination of potential financial crimes, traitorous activity and obstruction of justice could end up with him laundering prison clothes rather than money? As I’ve mentioned, I don’t think America is saved when Trump is toppled, but his ouster is necessary if we’re to have a chance to rescue our Republic and reform our government. Or maybe we’ll end up in another Civil War. Either or.

Trump will eventually be flushed down the vortex along with other waste products swirling around him, I’m fairly certain at this point, but as an amateur student of human psychology I’d be fascinated to know if he’s fully wrapped his declining brain around this scenario. Is it within his mental powers to grasp that some combination of potential financial crimes, traitorous activity and obstruction of justice could end up with him laundering prison clothes rather than money? As I’ve mentioned, I don’t think America is saved when Trump is toppled, but his ouster is necessary if we’re to have a chance to rescue our Republic and reform our government. Or maybe we’ll end up in another Civil War. Either or.

Elizabeth Drew, the great correspondent of the Watergate Era, cautions that any Trump impeachment process must be a gradual and bilateral one. Of course, we live in a faster age and a far more divided one, so I don’t know if that’s possible. It’s not that I don’t think McConnell and Ryan and the rest wouldn’t kick a sad old goat from a cliff to save their own hides, but I’m not sure that if Russian collusion is proved that it doesn’t pull way more Republicans over the precipice than we can currently guess. The GOP will fight such an outcome with all it has.

In a New York column about Trump’s possible ouster, Frank Rich cites Drew’s work and compares the slow-forming Watergate inferno to the fire next time. An excerpt:

Here’s Drew describing a typical Watergate day: “The news is coming too fast. Faster and harder than anyone expected. It is almost impossible to absorb.” And here she is a week after Nixon’s vice-president, Spiro Agnew, resigned upon pleading no contest to charges of bribery and tax fraud: “The city seems to be reeling around amidst the events and the breaking stories. In the restaurants, the noise level is higher. At the end of the day, someone says, ‘It’s like being drunk.’ ” It already feels like that right now.

One could argue that the context is different today — that the America of 2017 is not the America of the early 1970s. We think of our current culture as being harder to shock, easier to distract, and more inured to crude public figures who violate traditional societal norms as unabashedly as Trump. This, in theory, would make him harder to dislodge than Nixon, whose sins would more easily scandalize a relatively innocent 20th-century citizenry. But even without the internet’s cacophony, Nixon faced a post-1960s America as factionalized, jaded, and accustomed to shock as our own: It had witnessed the assassination of two Kennedys and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a complete overhaul of its mores as a consequence of a rising counterculture and women’s movement, and a domestic civil war precipitated by the catastrophe of Vietnam. The alarming toxicity of Trump has burst through the noise of our America much as Nixon’s did through his. And while the technology for delivering news makes it come faster and harder in 2017 than Drew or any of us could have anticipated in that day of daily newspapers and nightly news broadcasts, the onslaught of shocking developments felt no less overwhelming then than now.

Human nature hasn’t changed — not for those of us standing outside a teetering White House or for the cast of characters within. Much as Trump risked his presidency by empowering hotheaded ideologues like Michael Flynn and Steve Bannon, so Nixon’s White House had recruited the similarly reckless G. Gordon Liddy and E. Howard Hunt to wage war on the president’s perceived enemies. As John A. Farrell writes in his new, state-of-the-art Richard Nixon: The Life, both of them were “wannabe James Bonds.” Hunt, an alumnus of the CIA’s Bay of Pigs fiasco, was the prolific author of often pseudonymous spy novels, while Liddy was alt-right before it was cool: “a right-wing zealot, with a fixation for Nazi regalia and a kinky kind of Nietzschean philosophy,” who “organized a White House screening of the Nazi propaganda film Triumph of the Will.”

Though there are a number of areas where the Nixon and Trump narratives diverge, in nearly every case Trump’s deviations from the Watergate model make it even less likely that he will survive his presidency.•

Tags: Donald Trump, Elizabeth Drew, Frank Rich

John D. Rockefeller was America’s first billionaire, his fortune at its apex worth well over $300 billion in our terms. The son of a con man and a deeply devout mother, he was, quite appropriately, both very awful and very good, a merciless monopolist and a generous philanthropist. He donated hundreds of millions toward medical research and education, among other charities, and was known to hand out dimes–“Rockefeller dimes,” as they came to be called–to adults and children alike. The administering of those shiny ten-cent pieces–which were worth in 1928 roughly $1.40 by 2017 standards–was done both for propaganda purposes and because it amused the titan.

John D. Rockefeller was America’s first billionaire, his fortune at its apex worth well over $300 billion in our terms. The son of a con man and a deeply devout mother, he was, quite appropriately, both very awful and very good, a merciless monopolist and a generous philanthropist. He donated hundreds of millions toward medical research and education, among other charities, and was known to hand out dimes–“Rockefeller dimes,” as they came to be called–to adults and children alike. The administering of those shiny ten-cent pieces–which were worth in 1928 roughly $1.40 by 2017 standards–was done both for propaganda purposes and because it amused the titan.

From the February 18, 1928 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

Tags: John D. Rockefeller

10 search-engine keyphrases bringing traffic to Afflictor this week:

- will trump moderate?

- jack dorsey on trump and twitter

- thomas nast political cartoonist

- rev. billy sunday baseball preacher

- guglielmo marconi’s funeral

- bonnie and clyde getaway driver

- thomas mann at the white house

- the swami laura horos

- the wonderland murders

- the last straw was the dead doctor in the pool house

This week, the GOP may wreck healthcare, though I’m sure the doctors Americans will soon be able to afford will be fine.

• Something I wrote about the GOP in January seems truer now with American healthcare on life support.

• Identity politics allow the GOP to not worry about bad policy.

• Jack Ma thinks our technological revolution may lead to WWIII.

• Sue Halpern asks pertinent questions about “whistleblower” Julian Assange.

• Germany spied on the US as the US spied on Germany. Not at all surprising.

• Human moderators, not algorithms, scrub the worst of the Internet.

• A raft of technologists and futurists consider conscious machines.

• The Great Leveler author Walter Scheidel thinks further about wealth inequality.

• Andrew O’Hagan addresses the fate of the novel in our wired, unreal age.

• Tim Kurkjian predicts what the MLB will look like in 2037.

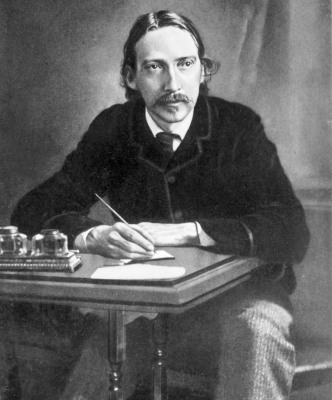

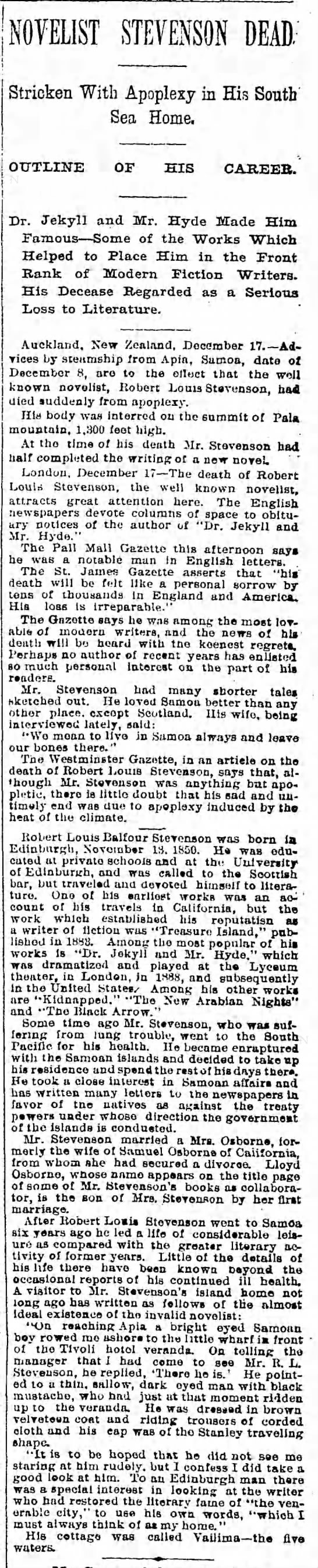

• Old Print Article: Robert Louis Stevenson dies in Samoa. (1894)

• A brief note from 1928 about pet giraffe prices.

• This week’s Afflictor keyphrase searches: Eugene Landy, MADCOMS, etc.

Jack Ma thinks our current technological age may lead to WWIII, but otherwise he’s pretty hopeful.

The Alibaba executive chairman recently told CNBC: “The first technology revolution caused World War I. The second technology revolution caused World War II. This is the third technology revolution.” His time frame for the possible global cataclysm is the next three decades, when many of us may be disrupted and disenchanted by improving Artificial Intelligence.

Chilling, sure, but China’s richest man also foresees 16-hour workweeks, wider markets for local products (Chinese consumption will be the engine that drives the world economy, he’s said) and plenty of new travel opportunities. My friends, you have to break some eggs to make that omelette.

If there will be blood, perhaps it’s appropriate that data is the new oil, as Louise Lucas of the Financial Times asserts in writing about the outsize success of Ma’s corporation. “Information collection,” a fairly benign term for the biggest gusher ever, is at the heart of the growth. An excerpt:

If data are the new oil, Jack Ma, former English teacher turned China’s richest man, is the new John D Rockefeller.

Like Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, Mr Ma’s Alibaba is a lucrative and rapidly growing business. Earlier this month, it forecast annual revenues would increase 45 to 49 per cent, besting analysts’ consensus estimates by 10 percentage points and adding $42.25bn to its value — almost an entire Barclays bank — the following day.

“Alibaba is evolving into a big data conglomerate,” enthused Jessie Guo, analyst at Jefferies, and one of the many who attended the group’s two-day investor conference in Hangzhou this month.

Revenue guidance and discussions at the event “indicate we are at the beginning of data-driven monetisation”, added Chi Tsang, head of internet research at HSBC.

Alibaba’s vertically and horizontally integrated services span shopping, movies, finance and logistics, all collecting information on people’s spending, location and viewing. Once refined, the data are fed back to merchants, who in turn can better target their goods and sell more over Alibaba’s ecommerce platforms.•

Tags: Jack Ma, Louise Lucas

IEEE Spectrum has an interesting article in which a raft of scientists and futurists are questioned about the ETA of conscious machines and their potential impact. Notably, nobody says such a development is impossible nor does anyone suggest pursuit of such has a good chance to extinct us.

Robin Hanson, author The Age of Em, sticks to his previous prognostication that our increasingly technological future may bring us an economy that doubles every month, which might seem inviting to a society in stagnation, but a world that could potentially “turn over” so quickly would be a shock to the system to anyone not gradually eased into it.

Marthine Rothblatt, the Sirius founder turned Transhumanist and developer of “consciousness software,” believes robots will largely be “good,” saying that she’s “confident the computers will be overwhelmingly friendly since they will be selected for in a Darwinian environment that consists of humanity. There is no market for [a] bad robot, no more than there is for a bad car or plane. Of course, there is the inevitability of a DIY bad human-level computer, but that gives me even more reason to welcome human-level cyberintelligence, because just like it takes a [thief to catch a thief], it will take a human-friendly smart computer to catch an antihuman smart computer.”

There’s also no market for terrorism or for genocide, but those things happen. We can’t avoid far stronger tools because of the human capacity to cause chaos, but we have to at least consider the possibility that our own doom is embedded in these advances.

Rodney Brooks is perhaps the most sober of all the participants. In Errol Morris’ 1997 documentary, Fast, Cheap and Out of Control, the roboticist famously says that in tomorrow’s world of intelligent machines, humans might not be necessary. Brooks, who has since backed off that statement (“You can’t expect me to stand by something I said during a long day of filming 20 years ago!”), now mocks what he believes to be reckless conjecture about the future.

An excerpt:

Question:

When will we have computers as capable as the brain?

Rodney Brooks:

Rodney Brooks’s revised question: When will we have computers/robots recognizably as intelligent and as conscious as humans?

Not in our lifetimes, not even in Ray Kurzweil’s lifetime, and despite his fervent wishes, just like the rest of us, he will die within just a few decades. It will be well over 100 years before we see this level in our machines. Maybe many hundred years.

Question:

As intelligent and as conscious as dogs?

Rodney Brooks:

Maybe in 50 to 100 years. But they won’t have noses anywhere near as good as the real thing. They will be olfactorily challenged dogs.

Question:

How will brainlike computers change the world?

Rodney Brooks:

Since we won’t have intelligent computers like humans for well over 100 years, we cannot make any sensible projections about how they will change the world, as we don’t understand what the world will be like at all in 100 years. (For example, imagine reading Turing’s paper on computable numbers in 1936 and trying to project out how computers would change the world in just 70 or 80 years.) So an equivalent well-grounded question would have to be something simpler, like “How will computers/robots continue to change the world?” Answer: Within 20 years most baby boomers are going to have robotic devices in their homes, helping them maintain their independence as they age in place. This will include Ray Kurzweil, who will still not be immortal.

Question:

Do you have any qualms about a future in which computers have human-level (or greater) intelligence?

Rodney Brooks:

No qualms at all, as the world will have evolved so much in the next 100+ years that we cannot possibly imagine what it will be like, so there is no point in qualming. Qualming in the face of zero facts or understanding is a fun parlor game but generally not useful. And yes, this includes Nick Bostrom.•

In the immediate aftermath of the GA-06 defeat of Jon Osoff, who has charisma on loan from Martin O’Malley, Liberal Twitter exhorted Democrats to develop a clearer policy message. When trying to win votes, it’s better to be lucid (except when it’s not), but policy isn’t what elevated Trump to the Oval Office–he had none–or Karen Handel to Congress. In addition to Kremlin machinations and FBI blunders, what enabled the Klu Klux Kardashian to be elected was his peddling of a deeply racist, xenophobic message that found the ready ears of nearly 63 million citizens. If lots of people are voting to Make America White Again, sound fiscal policy won’t make a dent.

It’s not that Dems can’t defeat such ugliness at the voting both–they’ve done it before and even won the popular tally in 2016–but they need the right candidate more than anything else. Someone bold and broadly appealing whose authenticity is unquestioned. Easier said than done, I suppose.

In the Slate piece “A GOP Without Fear,” Jamelle Bouie, who consistently rises above the clatter, argues that Republicans don’t fear the horrendous effects of a draconian reimagining of health care, the first attempt by either party to literally murder its base, since identity politics rule the day. In other words, you can’t fall from grace when grace itself isn’t valued.

An excerpt:

It’s likely that Republicans know the bill is unpopular and are doing everything they can to keep the public from seeing its contents before passing it. As we saw with the Affordable Care Act, the longer the process, the greater the odds for a major backlash. But this presupposes a pressing need to pass the American Health Care Act, which isn’t the case, outside of a “need” to slash Medicaid, thus paving the way for large-scale, permanent tax cuts. The Republican health care bill doesn’t solve any urgent problem in the health care market, nor does it represent any coherent vision for the health care system; it is a hodgepodge of cuts and compromises, designed to pass a GOP Congress more than anything. It is policy without any actual policy. At most, it exists to fulfill a promise to “repeal Obamacare” and cut taxes.

Perhaps that’s enough to explain the zeal to pass the bill. Republicans made a promise, and there are forces within the party—from hyperideological lawmakers and conservative activists to right-wing media and Republican base voters—pushing them toward this conclusion. When coupled with the broad Republican hostility to downward redistribution and the similarly broad commitment to tax cuts, it makes sense that the GOP would continue to pursue this bill despite the likely consequences.

But ultimately it’s not clear the party believes it would face those consequences. The 2018 House map still favors Republicans, and the party is defending far fewer Senate seats than Democrats. Aggressively gerrymandered districts provide another layer of defense, as does voter suppression, and the avalanche of spending from outside groups. Americans might be hurt and outraged by the effects of the AHCA, but those barriers blunt the electoral impact.

The grounds for political combat seem to have changed as well. If recent special elections are any indication—where GOP candidates refused to comment on signature GOP policies—extreme polarization means Republicans can mobilize supporters without being forced to talk about or account for their actual actions. Identity, for many voters, matters more than their pocketbooks. Republicans simply need to signal their disdain—even hatred—for their opponents, political or otherwise. Why worry about the consequences of your policies when you can preclude defeat by changing the ground rules of elections, spending vast sums, and stoking cultural resentment?•

Tags: Donald Trump, Jamelle Bouie

“Spying among friends, that isn’t done,” Angela Merkel has said, but the absolutely least surprising thing in this period of constant shocks is that Germany was apparently spying on America as America was spying on Germany. Of course.

Nearly three years ago, I assumed that at the very least “Germany didn’t want to delve too deeply into NSA spying because Germany has been complicit in it.” It isn’t surprising the surveillance was bilateral at least during the first decade of this century because one truism about the technological tools we’ve created is they will be used. The argument that we’ve managed to (mostly) not employ nuclear weapons so we can control privacy-obliterating devices is silly because these instruments and methods are decentralized and available to all, and governments and corporations and individuals will give in to the temptation to use them regardless of the law.

Also: Spying isn’t one big boom but instead death by a thousand cuts. Each individual act won’t feel calamitous. In Errol Morris parlance, these surveillance tools are fast, cheap and will continually be out of control.

From “German Intelligence Also Snooped on White House,” a Spiegel piece by Maik Baumgärtner, Martin Knobbe and Jörg Schindler:

Documents that Spiegel has been able to review show that the BND, until a few years ago, actually had considerable interest in the United States as a target of espionage. The document states that just under 4,000 search terms, or selectors, were directed against American targets between 1998 and 2006. It is unknown whether they continued to be used after those dates.

The German intelligence agency used the selectors to surveil telephone and fax numbers as well as email accounts belonging to American companies like Lockheed Martin, the space agency NASA, the organization Human Rights Watch, universities in several U.S. states and military facilities like the U.S. Air Force, the Marine Corps and the Defense Intelligence Agency, the secret service agency belonging to the American armed forces. Connection data from far over 100 foreign embassies in Washington, from institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Washington office of the Arab League were also accessed by the BND’s spies.

The entries also prove the existence of a top-secret anti-terror alliance between Western intelligence services, including those of Germany, the United States and France. Spiegel already reported back in 2005 on the elite unit, which is named Camolin. The papers now show several BND selectors were “Camolin-related.”

It’s Unlikely Spying Was Unintentional

Also on the selector list were lines at the U.S. Treasury Department, the State Department and the White House. Were they really all just “coincidental capture” as the former BND head claimed? Was it just an oversight?That’s unlikely.•

In January, I wrote this:

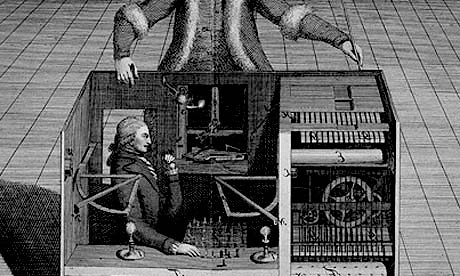

More than two centuries before Deep Blue deep-sixed humanity by administering a whooping to Garry Kasparov, that Baku-born John Henry, the Mechanical Turk purported to be a chess-playing automaton nonpareil. It was, of course, a fake, a contraption that hid within its case a genius-level human champion that controlled its every move. Such chicanery isn’t unusual for technologies nowhere near fruition, but the truth is even ones oh-so-close to the finish line often need the aid of a hidden hand.

In “The Humans Working Behind The Curtain,” a smart Harvard Business Review piece by Mary L. Gray and Siddharth Suri, the authors explain how the “paradox of automation’s last mile” manifests itself even in today’s highly algorithmic world, an arrangement by which people are hired to quietly complete a task AI can’t, and one which is unlikely to be undone by further progress. Unfortunately, most of the stealth work for humans created in this way is piecemeal, lower-paid and prone to the rapid churn of disruption.

An excerpt:

Cut to Bangalore, India, and meet Kala, a middle-aged mother of two sitting in front of her computer in the makeshift home office that she shares with her husband. Our team at Microsoft Research met Kala three months into studying the lives of people picking up temporary “on-demand” contract jobs via the web, the equivalent of piecework online. Her teenage sons do their homework in the adjoining room. She describes calling them into the room, pointing at her screen and asking: “Is this a bad word in English?” This is what the back end of AI looks like in 2016. Kala spends hours every week reviewing and labeling examples of questionable content. Sometimes she’s helping tech companies like Google, Facebook, Twitter, and Microsoft train the algorithms that will curate online content. Other times, she makes tough, quick decisions about what user-generated materials to take down or leave in place when companies receive customer complaints and flags about something they read or see online.

Whether it is Facebook’s trending topics; Amazon’s delivery of Prime orders via Alexa; or the many instant responses of bots we now receive in response to consumer activity or complaint, tasks advertised as AI-driven involve humans, working at computer screens, paid to respond to queries and requests sent to them through application programming interfaces (APIs) of crowdwork systems. The truth is, AI is as “fully-automated” as the Great and Powerful Oz was in that famous scene from the classic film, where Dorothy and friends realize that the great wizard is simply a man manically pulling levers from behind a curtain. This blend of AI and humans, who follow through when the AI falls short, isn’t going away anytime soon. Indeed, the creation of human tasks in the wake of technological advancement has been a part of automation’s history since the invention of the machine lathe.

We call this ever-moving frontier of AI’s development, the paradox of automation’s last mile: as AI makes progress, it also results in the rapid creation and destruction of temporary labor markets for new types of humans-in-the-loop tasks.•

The Harvard Business Review report was terrain previously covered from a different angle by Adrian Chen in Wired in 2014 with “The Laborers Who Keep Dick Pics and Beheadings Out of Your Facebook Feed.” The journalist studied those stealthily doing the psychologically dangerous business of keeping the Internet “safe.” The opening:

THE CAMPUSES OF the tech industry are famous for their lavish cafeterias, cushy shuttles, and on-site laundry services. But on a muggy February afternoon, some of these companies’ most important work is being done 7,000 miles away, on the second floor of a former elementary school at the end of a row of auto mechanics’ stalls in Bacoor, a gritty Filipino town 13 miles southwest of Manila. When I climb the building’s narrow stairwell, I need to press against the wall to slide by workers heading down for a smoke break. Up one flight, a drowsy security guard staffs what passes for a front desk: a wooden table in a dark hallway overflowing with file folders.

Past the guard, in a large room packed with workers manning PCs on long tables, I meet Michael Baybayan, an enthusiastic 21-year-old with a jaunty pouf of reddish-brown hair. If the space does not resemble a typical startup’s office, the image on Baybayan’s screen does not resemble typical startup work: It appears to show a super-close-up photo of a two-pronged dildo wedged in a vagina. I say appears because I can barely begin to make sense of the image, a baseball-card-sized abstraction of flesh and translucent pink plastic, before he disappears it with a casual flick of his mouse.

Baybayan is part of a massive labor force that handles “content moderation”—the removal of offensive material—for US social-networking sites. As social media connects more people more intimately than ever before, companies have been confronted with the Grandma Problem: Now that grandparents routinely use services like Facebook to connect with their kids and grandkids, they are potentially exposed to the Internet’s panoply of jerks, racists, creeps, criminals, and bullies. They won’t continue to log on if they find their family photos sandwiched between a gruesome Russian highway accident and a hardcore porn video. Social media’s growth into a multibillion-dollar industry, and its lasting mainstream appeal, has depended in large part on companies’ ability to police the borders of their user-generated content—to ensure that Grandma never has to see images like the one Baybayan just nuked.

So companies like Facebook and Twitter rely on an army of workers employed to soak up the worst of humanity in order to protect the rest of us. And there are legions of them—a vast, invisible pool of human labor.•

Chen has now teamed with Ciarán Cassidy to revisit the harrowing topic for a 20-minute documentary called “The Moderators.” It’s a fascinating peek into a hidden corner of our increasingly computerized world–one that’s even more relevant in the wake of the Kremlin-bot Presidential election–as well as very good filmmaking.

We watch as trainees at an Indian company that quietly “cleans” unacceptable content from social-media sites are introduced to sickening images they must scrub. That tired phrase “you can’t unsee this” gains new currency as the neophytes are bombarded by shock and gore. The movie numbers at 150,000 the workers in this sector trying to mitigate the chaos in the “largest experiment in anarchy we’ve ever had.” For these kids it’s a first job, a foot in the door even if they’re stepping inside a haunted house. You have to wonder, though, if they will ultimately be impacted in a Milgramesque sense, desensitized and disheartened, whether they initially realize it or not.

We are all like the moderators to a certain degree, despite their best efforts. Pretty much everyone who’s gone online during these early decades of the Digital Age has witnessed an endless parade of upsetting images and footage that was never available during a more centralized era. Are we also children who don’t realize what we’re becoming?

Tags: Adrian Chen, Ciarán Cassidy

The text below I wrote just prior to the Trump Inauguration to preface an article about the GOP trying to gut the House’ outside ethics watchdog. It came to mind today again when thinking about Republican efforts to pass a draconian healthcare bill, with the “softer” Senate version being even worse in some ways.

REVEALED: Senate bill kicks millions off healthcare and contains deeper cuts to Medicaid, just phases them in more slowly. No thanks. https://t.co/xMKcaiwSFL

— Adam Schiff (@RepAdamSchiff) June 22, 2017

At some point, things fall apart. It’s terrifying to even think about.

From January 2:

No one won the 2016 American Presidential election. Not really.

I don’t mean in a figurative sense that we all lose because a fascist kleptocrat will soon be in the Oval Office, though, yes, of course, there’s that. I’m saying that not only did most of the people vote for the losing candidate, but even those who chose Trump aren’t in favor of GOP policies.

Apart from his most blindly enthusiastic supporters, few Americans are deluded about Trump, even those who pulled the pin with his name. They do not like him. He was used as a blunt instrument, a brick to toss through the window, a way to send a message that a corrupt and broken system must immediately be repaired. The Republicans now seem to have forgotten that they’re inside that building and that the approval ratings of this congress are at historic lows. Because they are avaricious opportunists, they likely will not notice that the whole thing is apt to be burned down if the cries are ignored. Trump, as miscast as may have been as a messenger for the disgruntled, working-class masses, was the final warning.

It’s a message that will almost definitely go unheeded. Republicans believe Americans want Obamacare repealed (they don’t), Medicare gutted (no, again), Social Security privatized (nope), unions demolished (wait a minute) and tax cuts for the highest earners (um, what?). Mitch McConnell, a creature from the black lagoon, is convinced citizens don’t really want the swamp drained, blithely unaware there may be a meat hook with his name on it.

Those who most feel like they’re bleeding are about to be bled dry. I’m not suggesting supporters of the orange supremacist deserve a whole lot of pity. I mean, I would play the world’s smallest violin for them, but the GOP just cut the school music program.

I’m really not joking, though. The GOP’s complete misunderstanding of the moment may provoke very bad things, “unspeakable things” in the President-Elect’s reckless lingo. People have tired of bread and Kardashians, and some sort of breaking point feels near. Even a good agnostic like myself can say “God help us all.”•

Gained much insight early in the year from reading Walter Scheidel’s The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century, which analyzes how wealth inequality can be interrupted and reversed, his analysis stretching back far earlier than the Gini coefficient to the time of the development of rudimentary tools like spears.

How do we make the world more equal? To put it simply, through great pain, unless you’re into mass mobilization warfare, plague, bloody revolution or societal collapse. (I think Steve Bannon is deeply in love with at least two or three of these options, though not to make the economy more equal.) Of course, leveling doesn’t necessarily mean the raising of all boats but sometimes the sinking of every last ship. Scheidel asserts that wealth inequality has been the logical outcome of stable societies, with leveling occurring for relatively brief spells by virtue of the sweep of history or the spread of Influenza.

The book isn’t entirely resigned, believing that perhaps past won’t be prologue, holding out hope that human progress can find new means of mitigation. Of course, sitting here at this moment in time, that doesn’t look like the plausible near-term scenario.

Scheidel has just published a smart essay for Aeon wondering anew if we can arrive at a more-equal playing field with trampling all the players. He isn’t sanguine about our chances, thinking genetic engineering may further complicate matters. An excerpt:

History offers very little comfort to those in search of peaceful levelling. To be sure, it is perfectly possible to reduce inequality at the margins: if Latin American countries have done it, the US, UK or Australia certainly ought to be able to accomplish the same, using an array of policy measures, from fiscal interventions, basic incomes and the targeting of concealed offshore wealth, to carefully focused investment in education and campaign finance reform. However, policymaking does not take place in a vacuum, and not everything that worked well for the postwar generation, say, could be easily implemented in today’s more globally integrated, competitive and deregulated environment. Throughout history, truly substantial compressions of inequality invariably had much darker origins, and no similarly powerful alternative mechanisms have since emerged.