WE ARE at the threshold today of our first bold venture into space. Scientists and engineers working toward man’s exploration of the great new frontier know now that they are going to send aloft a robot laboratory as the first step—a baby space station which for 60 days will circle the earth at an altitude of 200 miles and a speed of 17,200 miles an hour, serving as scout for the human pioneers to follow.

We rocket engineers have learned a lot about space by shooting off the high-flying rockets now in existence—so much that right now we know how to build the rocket ships and the big space station we need to put man into space and keep him there comfortably. We know how to train space crews and how to protect them from the hazards which exist above our atmosphere. All that has been reported in previous issues ofCollier’s.

But the rockets which have gathered our data have stayed in space for only a few minutes at a time. The baby satellite will give us 60 days; we’ll learn more in those two months than in 10 years of firing the present instrument rockets.

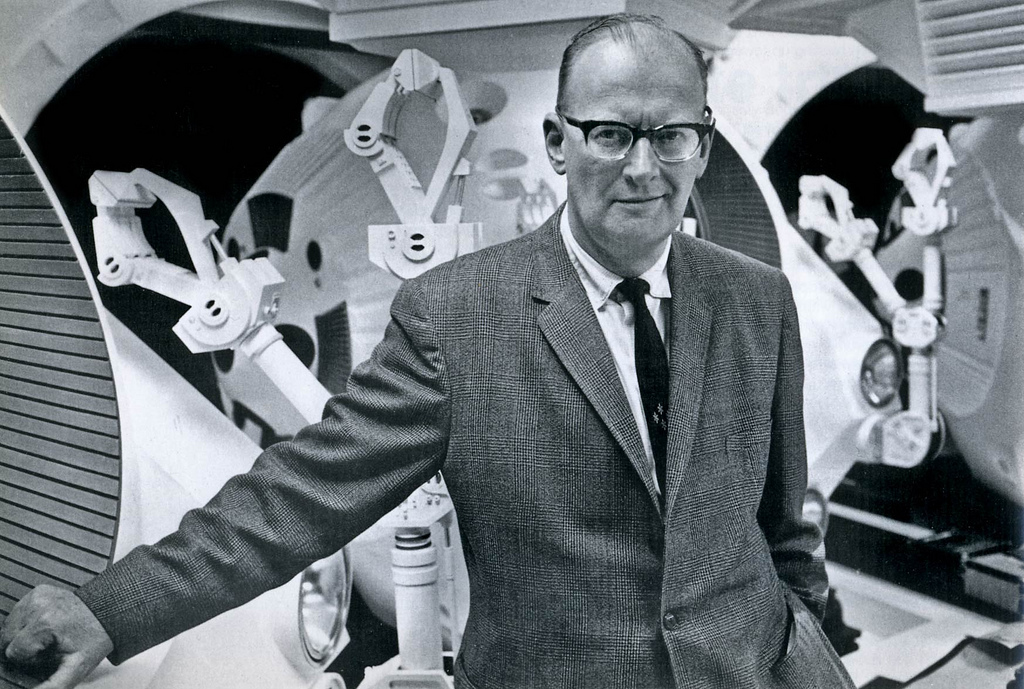

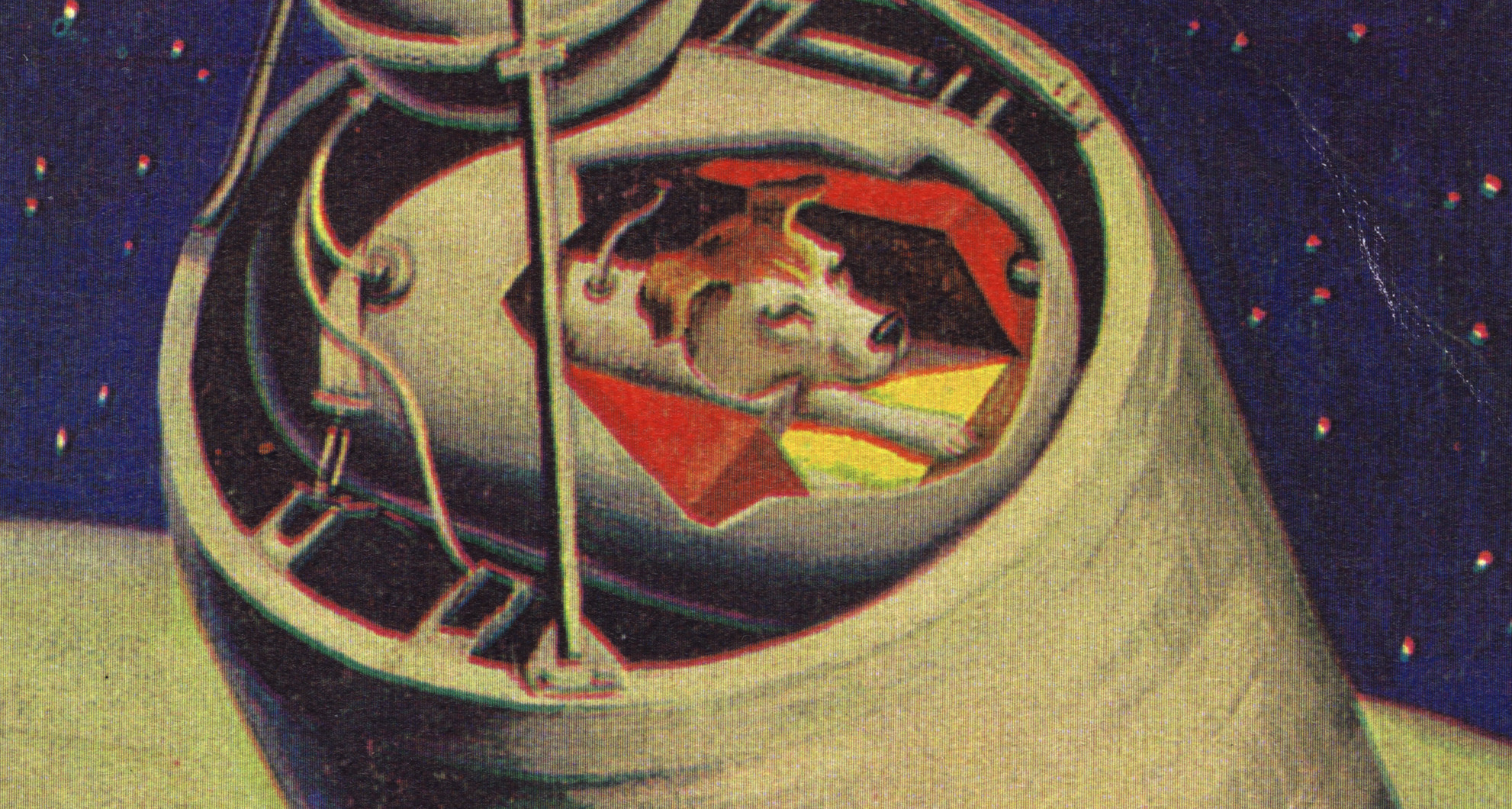

We can begin work on the new space vehicle immediately. The baby satellite will look like a 30-foot ice-cream cone, topped by a cross of curved mirrors which draw power from the sun. Its tapered casing will contain a complicated maze of measuring instruments, pressure gauges, thermometers, microphones and Geiger counters, all hooked up to a network of radio, radar and television transmitters which will keep watchers on earth informed about what’s going on inside it.

Speeding 30 times faster than today’s best jets, the little satellite will make one circuit around the earth every 91 minutes—nearly 16 round trips a day. At dawn and dusk it will be visible to the naked eye as a bright, unwinking star, reflecting the sun’s rays and traveling from horizon to horizon in about seven minutes. Ninety-one minutes later, it completes the circuit—but if you look for it in the same place, it won’t be there: it travels in a fixed orbit, while the earth, rotating on its own axis, moves under it. An hour and a half from the time you first sighted the speeding robot, it will pass over the earth hundreds of miles to the west. The cone will never be visible in the dark of night, because it will be in the shadow of the earth.

If you live in Philadelphia, one morning you may see the satellite overhead just before sunup, moving on a southeasterly course. Ninety-one minutes later, as dawn breaks over Wichita, Kansas, people there will see it, and after another hour and a half it will be visible over Los Angeles—again, just before the break of dawn.

That evening, Philadelphians—and the people of Wichita and Los Angeles—will see the speeding satellite again, this time traveling in a northeasterly direction. The following morning, it will be in sight again over the same cities, at about the same time, a little farther to the west.

After about ten days, it will no longer appear over those three cities, but will be visible over other areas. Thus, from any one site, it will be seen on successive occasions for about 20 days before disappearing below the western horizon. In another month or so, it will show up again in the east. And while you’re gazing at the little satellite, it will be peering steadily back, through a television camera in its pointed nose. The camera will give official viewers in stations scattered around the globe the first real panoramic picture of our world—a breath-taking view of the land masses, oceans and cities as seen from 200 miles up. More than likely, commercial TV stations will pick up the broadcasts and relay them to your home.

Three more cameras, located inside the cone, will transmit equally exciting pictures: the first sustained view of life in space.

Three rhesus monkeys—rhesus, because that species is small and highly intelligent—will live aboard the satellite in air-conditioned comfort, feeding from automatic food dispensers. Every move they make will be watched, through television, by the observers on earth.

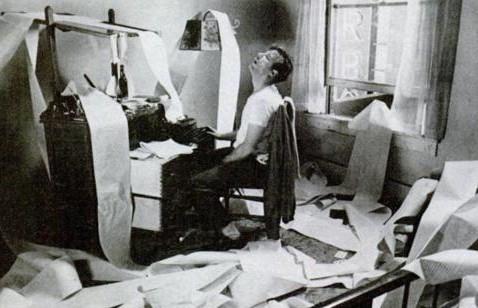

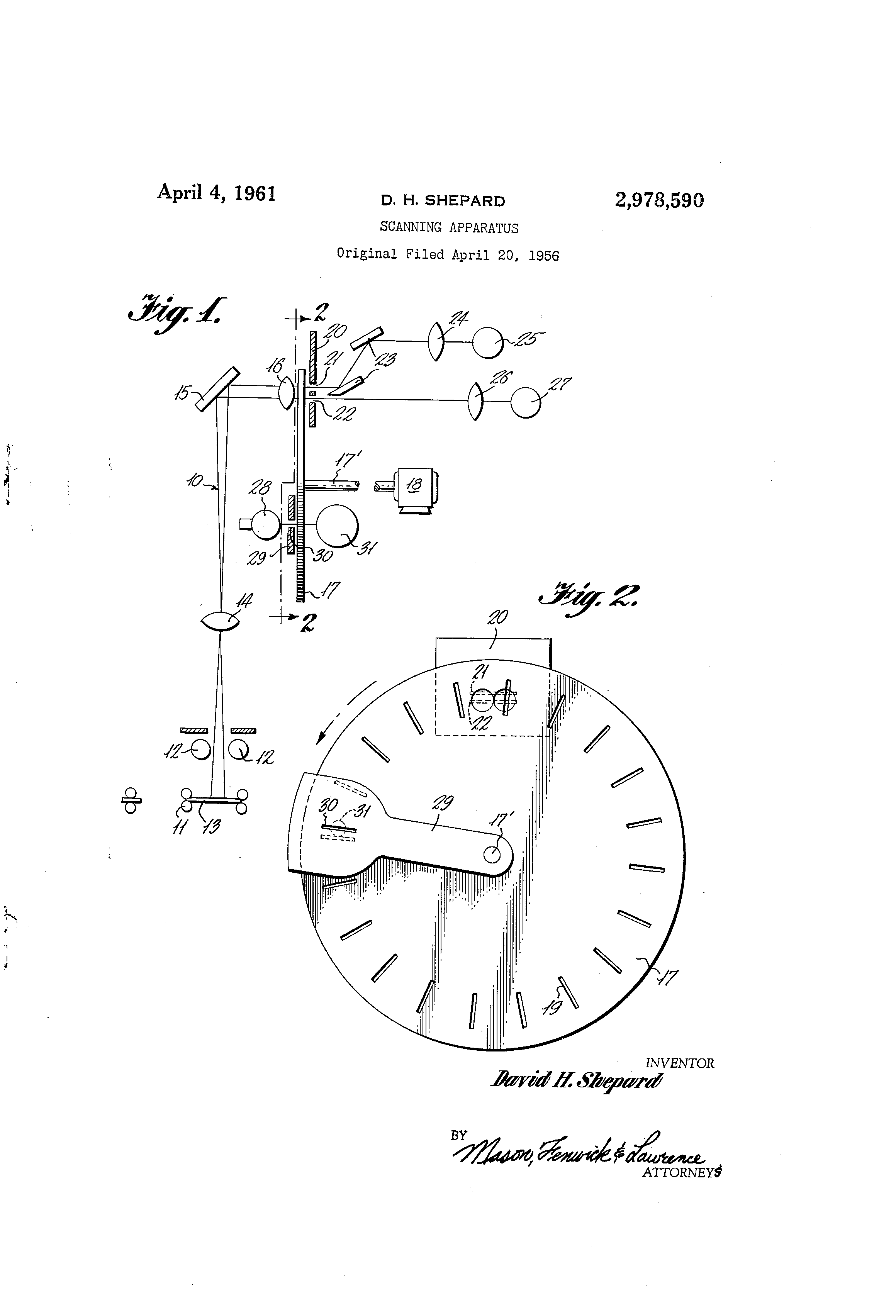

As fast as the robot’s recording instruments gather information, it will be flashed to the ground by the same method used now in rocket-flight experiments. The method is called telemetering, and it works this way: as many as 50 reporting devices are hooked to a single transmitter which sends out a jumble of tonal waves. A receiver on earth picks up the tangled signals, and a decoding machine unscrambles the tones and prints the information automatically on long strips of paper, as a series of spidery wavelike lines. Each line represents the findings of a particular instrument—cabin temperature, air pressure and so on. Together, they’ll provide a complete story of the happenings inside and outside the baby space station.

What kind of scientific data do we hope to get? Confirmation of all space research to date and, most important, new information on weightlessness, cosmic radiation and meteoric dust.

At a high enough speed and a certain altitude, an object will travel in an orbit around the earth. It— and everything in it—will be weightless. Space scientists and engineers know that man can adjust to weightlessness, because pilots have simulated the condition briefly by flying a jet plane in a rollercoaster arc. But will sustained weightlessness raise problems we haven’t foreseen? We must find out—and the monkeys on the satellite will tell us.

The monkeys will live in two chambers of the animal compartment. In the smaller section, one of the creatures will lie strapped to a seat throughout the two-month test. His hands and head will be free, so he can feed himself, but his body will be bound and covered with a jacket to keep him from freeing himself or from tampering with the measuring instruments taped painlessly to his body. The delicate recording devices will provide vital information—body temperature, breathing cycle, pulse rate, heartbeat, blood pressure and so forth.

The other two monkeys, separated from their pinioned companion so they won’t turn him loose, will move about freely in the larger section. During the flight from earth, these two monkeys will be strapped to shock-absorbing rubber couches, under a mild anesthetic to spare them the discomfort of the acceleration pressure. By the time the anesthetic wears off, the robot will have settled in its circular path about the earth, and a simple timing device will release the two monkeys. Suddenly they’ll float weightless, inside the cabin.

What will they do? Succumb to fright? Perhaps cower in a corner for two months and slowly starve to death? I don’t think so. Chances are they’ll adjust quickly to their new condition. We’ll make it easier for them to get around by providing leather handholds along the walls, like subway straps, and by stringing a rope across the chamber.

There’s another problem for the three animals: to survive the 60 days they must eat and drink.

They’ll prepare to cope with that problem on the ground. For months before they take off, the two unbound monkeys will live in a replica of the compartment they’ll occupy in space, learning to operate food and liquid dispensers. In space, each of the two free animals will have his own feeding station. At specific intervals a klaxon horn will sound; the monkeys will respond by rushing to the feeding stations as they’ve been trained to do. Their movement will break an electric-eye beam, and clear plastic doors will snap shut behind them, sealing them off from their living quarters. Then, while they’re eating, an air blower will flush out the living compartment—both for sanitary reasons and to keep weightless refuse from blocking the television lenses. The plastic doors will spring open again when the housecleaning is finished.

The monkeys will drink by sucking plastic bottles. Liquid left free, without gravity to keep it in place, would hang in globules. To get solid food, each of the monkeys—again responding to their training—will press a lever on a dispenser much like a candy or cigarette machine. The lever will open a door, enabling the animals to reach in for their food. They’ll get about half a pound of food a day—a biscuit made of wheat, soybean meal and bone meal, enriched with vitamins. The immobilized monkey will have the same food; his dispensers will be within easy reach.

For the two free monkeys, it will be a somewhat complicated life. The way they react to their ground training under the new conditions posed by lack of gravity will provide invaluable information on how weightlessness will affect them.

While the monkeys are providing physiologists with information on weightlessness, physicists will be learning more about cosmic rays, invisible high-speed atomic particles which act like deep penetrating X rays and were once feared as the major hazard of space flight. Theoretically, in large enough doses cosmic rays could conceivably cause deep burns, damage the eyes, produce malignant growths and even upset the normal hereditary processes. They don’t do much damage to us on earth because the atmosphere dissipates their full strength, but before much was known about the rays people worried about the dangers they might pose to man in space. From recent experiments scientists now know that the risk was mostly exaggerated—that even beyond the atmosphere a human can tolerate the rays for long periods without ill effects. Still, the best figures available have been obtained by high-altitude instrument rocket flights which were too brief to be conclusive. These spot checks must be augmented by a prolonged study, and the baby space station will make that possible.

The concentration of cosmic rays over the earth varies, being greatest over the north and south magnetic poles. The baby space station will follow a circular path that will carry it close to both poles within every hour and a half, so it can determine if cosmic-ray concentration varies that high up.

Geiger counters inside and outside the robot will measure the number of cosmic particle hits. The telemetering apparatus will signal the information to the ground—and for the first time physicists will have an accurate indication of the cosmic-ray concentration in space, above all parts of the globe.

Besides cosmic rays, the baby satellite will be hit by high-speed space bullets—tiny meteors, most of them smaller than a grain of sand, whizzing through space faster than 1,000 miles a minute.

When men enter space, they’ll be protected against these pellets. Their rockets, the big space station, even their space suits, will have an outer skin called a meteor bumper, which will shatter the lightning-fast missiles on impact. But how many grainiike meteors must the bumpers absorb every 24 hours? That’s what we space researchers want to know. So dime-sized microphones will be scattered over the robot’s outer skin to record the number and location of the impacts as they occur.

In the process of unmasking the secrets of space, the baby satellite also will unravel a few riddles of our own earth.

For example, there are numerous islands whose precise position in the oceans has never been accurately established because there is no nearby land to use as a reference point. Some of them—one is Bouvet Island, lying south of the Cape of Good Hope—have been the subject of international disputes which could be quickly settled by fixing the islands’ positions. By tracking the baby space station as it passes over these islands, we’ll accurately pinpoint their locations for the first time.

The satellite will be even more important to meteorologists. The men who study the weather would like to know how much of the earth is covered with cloud in any given period. The robot’s television camera will give them a clue—a start toward sketching in a comprehensive picture of the world’s weather. Moreover, by studying the pattern of cloud movement, particularly over oceans, they may learn how to predict weather fronts with precision months in advance. Most of the weather research must await construction of a man-carrying space station, but the baby satellite will show what’s needed.

To collect this information, of course, we must first establish the little robot in its 200-mile orbit. All the knowledge needed for its construction and operation is already available to experts in the fields of rocketry, television and telemetering.

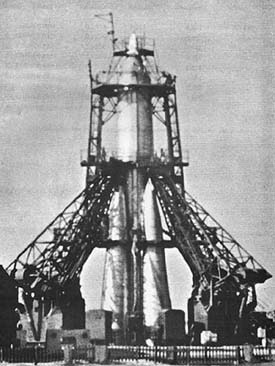

Before take-off, the satellite vehicle will resemble one of today’s high-altitude rockets, except that it will be about three times as big—150 feet tall, and 30 feet wide at the base. After take-off it will become progressively smaller, because it actually will consist of three rockets—or stages—one atop another, two of which will be cast away after delivering their full thrust. The vehicle will take off vertically and then tilt into a shallow path nearly parallel to the earth. Its course will be over water at first, so the first two stages won’t fall on anyone after they’re dropped, a few minutes after take-off.

When the third stage of the vehicle reaches an altitude of 60 miles and a speed of 17,700 miles an hour, the final bank of motors will shut off automatically. The conical nose section will coast unpowered to the 200-mile orbit, which it will reach at a speed of 17,100 miles an hour, 44 minutes later. The entire flight will take 48 1/2 minutes.

After the satellite reaches its orbit, the automatic pilot will switch on the motors once again to boost the velocity to 17,200 miles an hour—the speed required to balance the earth’s gravity at that altitude. Now the rocket becomes a satellite; it needs no more power but will travel steadily around the earth like a small moon for 60 days, until the slight air drag present at the 200-mile altitude slows it enough to drop.

Once the satellite enters its orbit, gyroscopically controlled flywheels cartwheel the nose until it points toward the earth. At the same time, five little antennas spring out from the cone’s sides and a small explosive charge blasts off the nose cap which has guarded the TV lens during the ascent.

Finally, the satellite’s power plant—a system of mirrors which catch the sun’s rays and turn solar heat into electrical energy—rises into place at the broad end of the cone. A battery-operated electric timer starts a hydraulic pump, which pushes out a telescopic rod. At the end of the rod are the three curved mirrors. When the rod is fully extended, the mirrors unfold, side by side, and from the ends of the central mirror two extensions slip out. Mercury-filled pipes run along the five polished plates; the heated mercury will operate generators providing 12 kilowatts of power. Batteries will take over the power functions while the satellite is passing through the shadow of the earth.

With the power plant in operation, the baby space station buckles down to its 60-day assignment as man’s first listening post in space.

At strategic points over the earth’s surface, 20 or more receiving stations, most of them set up in big trailers, will track the robot by radar as it passes overhead, and record the television and telemetering broadcasts on tape and film. Because the satellite’s radio waves travel in a straight line, the trailers can pick up broadcasts for just a few minutes at a time—only while the robot remains in sight as it zooms from horizon to horizon.

As the satellite passes out of range, the recorded data will be sent to a central station in the United States—some of it transmitted by radio, the rest shipped by plane. There, the information will be evaluated and integrated from day to day.

The monitoring posts will be set up inside the Arctic and Antarctic Circles and at points near the equator. In the polar areas, stations could be at Alaska, southern Greenland and Iceland; and in the south, Shetland Islands, Campbell Island and South Georgia Island. In the Pacific, possible sites are Baker Island, Christmas Island, Hawaii and the Galapagos Islands.

The remaining monitors may be located in Puerto Rico, Bermuda, St. Helena, Liberia, South-West Africa, Ethiopia, Maldive Islands, the Malay Peninsula, the Philippines, northern Australia and New Zealand. These points, all in friendly territory, would form a chain around the earth, catching the satellite’s broadcasts at least once a day.

The monitor stations will be fairly costly, but they’ll come in handy again later, when man is ready to launch the first crew-operated rocket ships for development of a big-manned space station, 1,075 miles from the earth.

The cost of the baby satellite project will be absorbed into the four-billion-dollar 10-year program to establish the bigger satellite. We scientists can have the baby rocket within five to seven years if we begin work now. Five years later, we could have the manned space station.

One of the monitoring posts will view the last moments of the baby space station. As the weeks pass, the satellite, dragging against the thin air, will drop lower and lower in its orbit. When it descends into fairly dense air, its skin will be heated by friction, causing the temperature to rise within the animal compartments. At last, a thermostat will set off an electric relay which triggers a capsule containing a quick-acting lethal gas. The monkeys will die instantly and painlessly. Soon afterward, the telemetering equipment will go silent, as the rush of air rips away the solar mirrors which provide power, and the baby space station will begin to glow cherry red. Then suddenly the satellite will disappear in a long white streak of brilliant light—marking the spectacular finish of man’s first step in the conquest of space.•

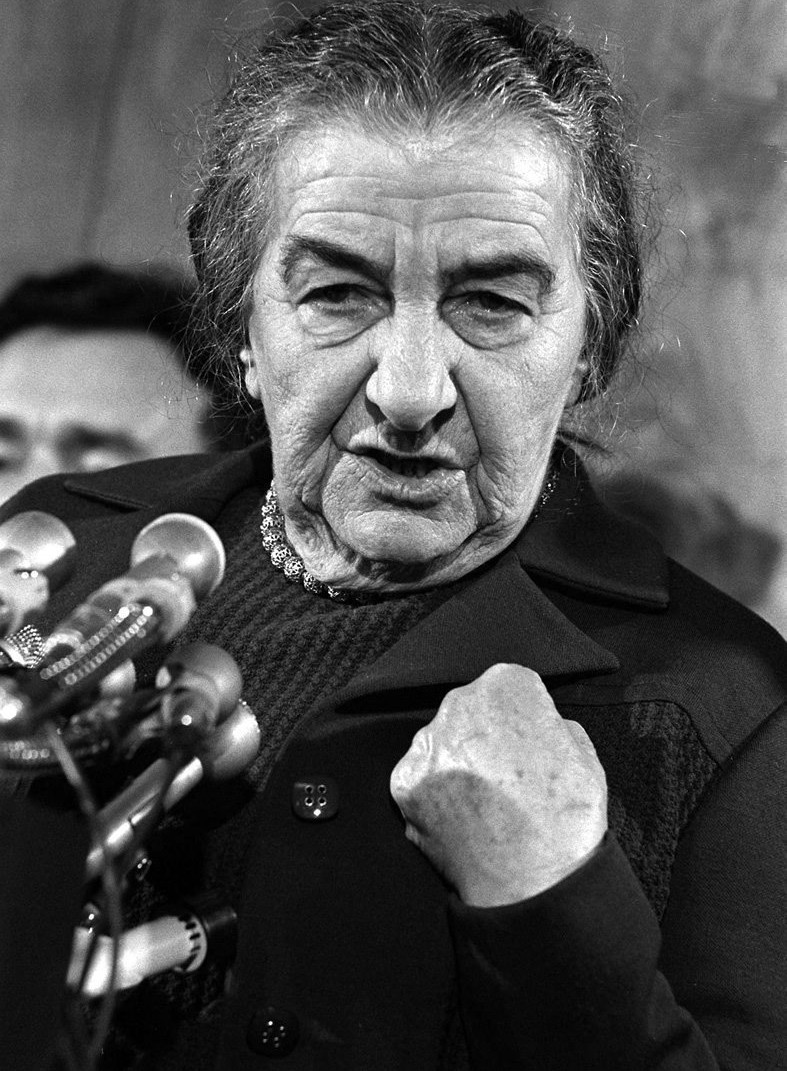

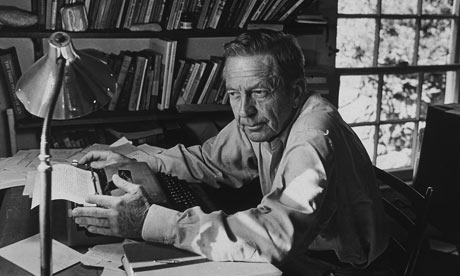

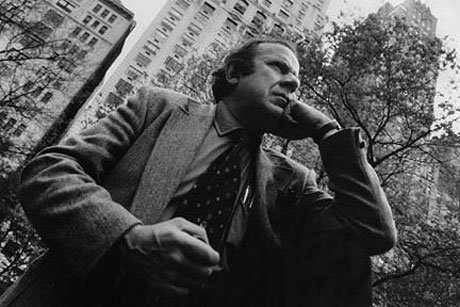

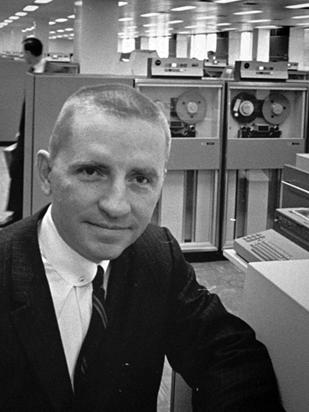

In 1969, computer-processing magnate Ross Perot had a McLuhan-ish dream: an electronic town hall in which interactive television and computer punch cards would allow the masses, rather than elected officials, to decide key American policies. In 1992, he held fast to this goal–one that was perhaps more democratic than any society could survive–when he bankrolled his own populist third-party Presidential campaign. The opening of

In 1969, computer-processing magnate Ross Perot had a McLuhan-ish dream: an electronic town hall in which interactive television and computer punch cards would allow the masses, rather than elected officials, to decide key American policies. In 1992, he held fast to this goal–one that was perhaps more democratic than any society could survive–when he bankrolled his own populist third-party Presidential campaign. The opening of In Lauren Weiner’s

In Lauren Weiner’s