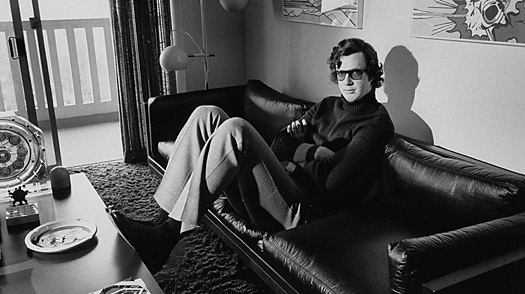

In 1990, during the mercifully short-lived Deborah Norville era of the Today Show, Michael Crichton stops by to discuss his just-published novel, Jurassic Park.

You are currently browsing the archive for the Videos category.

Tags: Deborah Norville, Michael Crichton

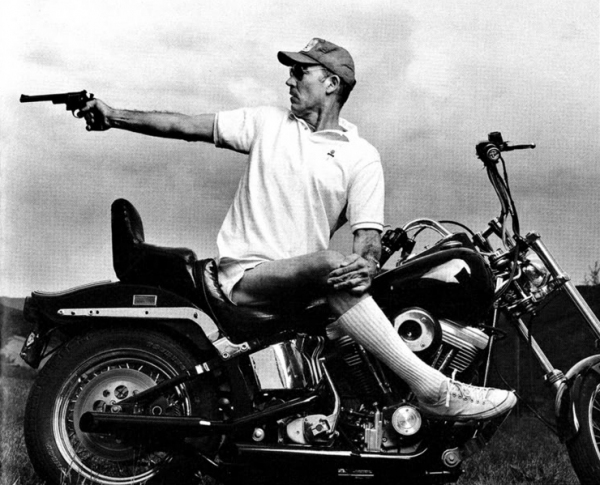

Wilt Chamberlain was a remarkable athlete (basketball, volleyball, track and field), but it’s probably a good thing he never realized his dream to fight Muhammad Ali. Howard Cosell presides over the ridiculousness, as he often did.

From East Side Boxing:

Springtime, 1971. Inside an office within the Houston Astrodome, a most unusual negotiation is about to take place. Seated at one end of the table is Muhammad Ali, former Heavyweight Champion of the World and self-proclaimed greatest fighter of all time. Next to him: Bob Arum, the former Justice Department attorney turned boxing promoter who had worked with Ali since his 1966 fight with George Chuvalo.

A few minutes later, they are joined by one of the most imposing figures in all of sport, the towering titan of professional basketball Wilt Chamberlain. Ali and Chamberlain knew each other well and had appeared together on numerous occasions in the past, from television talk shows to press conferences addressing civil rights issues. The purpose of this meeting, however, was far different from their previous encounters.

Today no media cameras are present, no reporters scramble for sound bites. The two most famous athletes in the world isolated themselves within the cavernous empty stadium to quietly discuss an event without precedent in the annals of sport. For on this day, Muhammad Ali and Wilt Chamberlain will agree to face each other in a 15-round boxing match, to be held in the Astrodome on July 26, 1971.

For Chamberlain, fighting Ali represented the pinnacle in his quest to conquer not only his own sport, but the entire sporting world.•

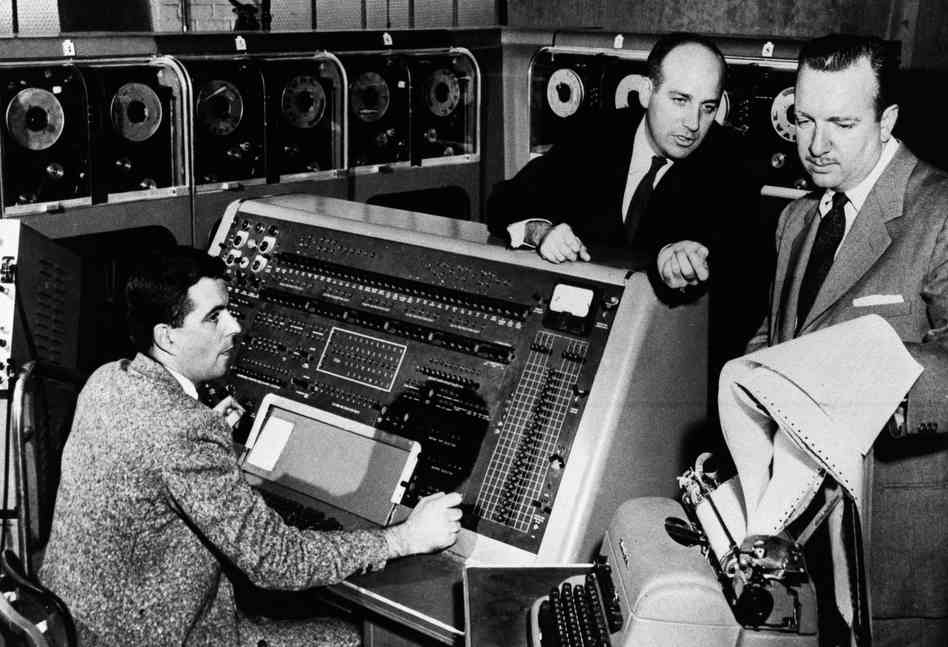

The Univac 1 computer got off to a good start in 1952 when it predicted that Eisenhower would win easily over Stevenson even though the press thought the reverse outcome was a near-certainty. It faltered a bit in the 1954 midterm Senate races and was mocked. (“Tilt!” was hollered in the newsroom by one wiseass when it became clear that the prognostications were errant.) But by the 1956 Presidential election, the computer once more nailed the Eisenhower triumph over Stevenson. No TV broadcast of any major election ever went without a computer again.

In this 1952 clip, Walter Cronkite cedes the floor the machine which at this early point in the night thought Eisenhower was a 100-1 favorite to win. Nervous CBS brass were so concerned that the “electronic brain” was wrong that they initially pretended it had mechanical difficulties and was being unresponsive.

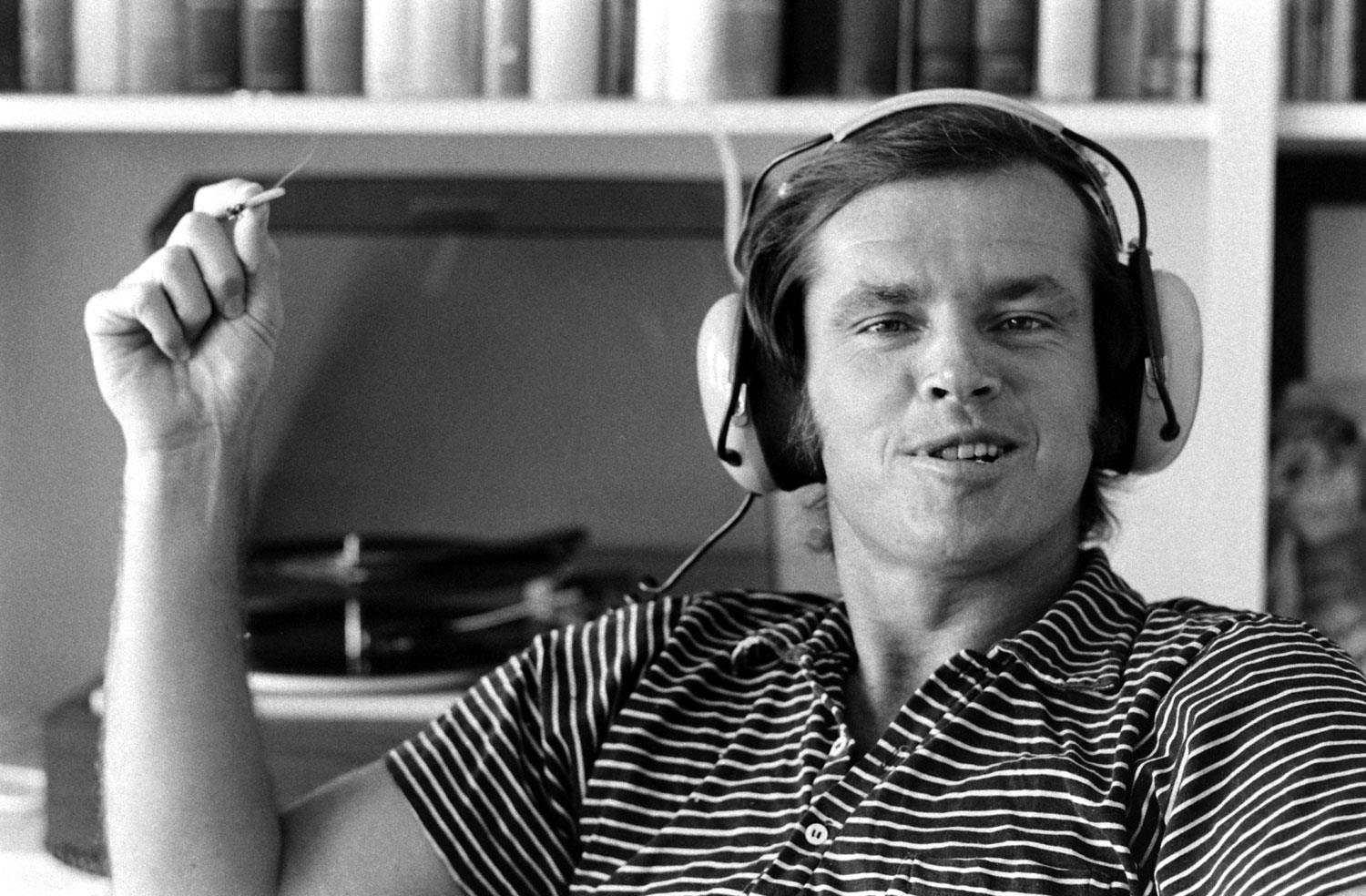

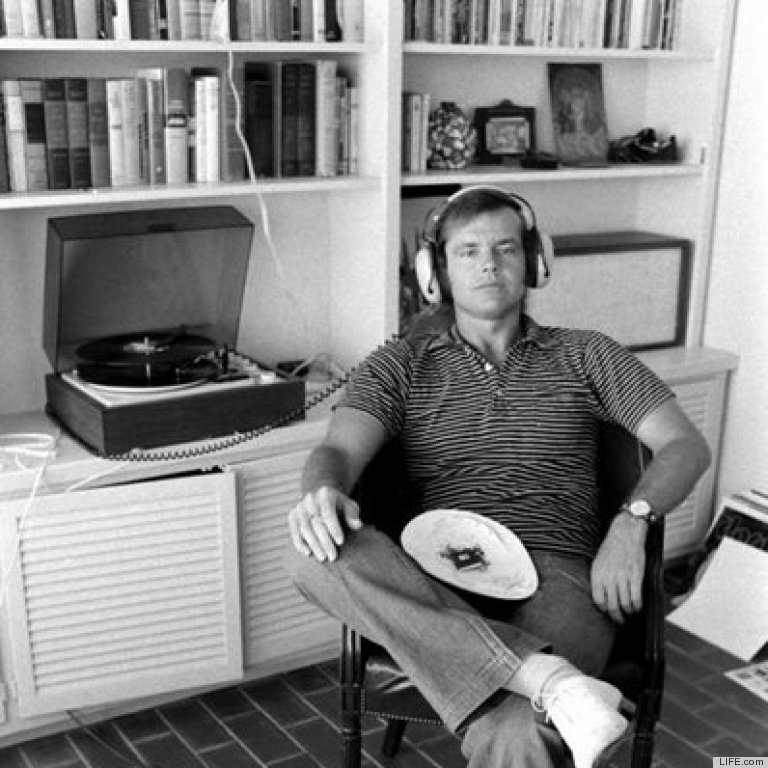

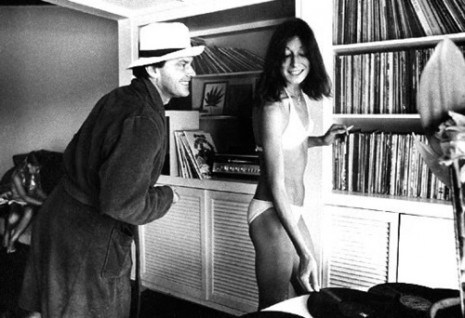

I don’t collect books or records or anything. I love well-designed, beautiful things that make me happy, but I don’t have a deep need to own them. (Jack Nicholson and Anjelica Huston, photographed in 1971 by Julian Wasser, disagreed with me on this matter.) From a Guardian piece about the value of vinyl by Marc Maron, who seems wonderful from a distance:

“The appeal of vinyl is a mysterious thing. Even when you talk to people who make records, who know how the sound gets from the groove to the stylus into the amp and out through the speakers, it’s still kind of magical, in some weird way. The idea of analog, even with its crackle and pops, the idea of this sound being pulled off this rotating disc through these other elements, I think there’s integrity to that, as opposed to this mystifying sequence of zeroes and ones that make that digital sound. I have no idea how the hell that works. It seems detached, inhuman.

At some point in the last two years, I got a renewed interest in playing records. I’d had turntables before, and I had a box of records that I’d been carting around since high school. I always knew in the back of my head that records had more integrity than digital music. I went to interview Jack White at his place in Nashville, and he’s a real analog guy. He had these Mackintosh tube amps, and I got hung up on the idea of getting a tube amp, but the ones Jack had were $15,000. There was no way I could spend that kind of money on stereo equipment and enjoy it; I’d always be thinking, does this sound like $15,000? I don’t think so.

I’ve got around 2,000 records now, and I play music constantly.”

_____________________________

“Are you fed up with constantly searching for the records you want?”

Tags: Anjelica Huston, Jack Nicholson, Julian Wasser, Marc Maron

That joker Alan Abel plays pranks that work because beneath the ridiculous set-ups and crude one-liners there’s an understanding of our desires and fears. In this ridiculous interview from basic cable decades ago, he satirized our wish for fame, youth and immortality, marrying the emerging celebrity culture to new scientific possibilities. He pretended that he’d created a sperm bank in which only stars like John Wayne and Johnny Carson were allowed to make deposits. And he was going to cryogenically freeze a young woman and tour her body across America. Everyone would be a star and live forever.

Fertilizing a human egg in a test tube was considered verboten and scary by many when the first child to be conceived in this fashion, Louise Brown, was born in 1978. Ethicists and religious figures questioned the process. All the fuss seems silly in retrospect, and the procedure is now just another way to have a baby. Louise indeed has had a normal life, as a nurse and postal worker and mom (the in vivo kind), despite a continuous crush of press interview requests. Here she is a lively child of 14 months on a Canadian talk show with her mom and dad.

Tags: Louise Brown

Here’s the full 22-minute version of Paul Ryan’s excellent 1969 documentary, “Ski Racing,” which uses bold editing and FM radio rock to help profile that era’s world-class downhill racers. One of the pros included is Vladimir “Spider” Sabich who would die horribly in 1976 in an infamous crime.

From the 1974 Sports Illustrated article, “The Spider Who Finally Came In From The Cold“:

In selling the tour, the sales pitch is not pegged strictly to exciting races and the crack skiers but also to its colorful personalities. There is Sabich, who flies, races motorcycles and figures that a night in which he hasn’t danced on at least one tabletop is a night wasted. Jim Lillstrom, Beattie’s P.R. man, also enjoys checking off some of the other characters.Norway’s Terje Overland is known as the Aquavit Kid for the boisterous post-victory celebrations he has thrown. He’s also been known to pitch over a fully laden restaurant table when the spirits have so moved him. Then there is the poet, Duncan Cullman, of Twin Mountain, N.H., author of The Selected Heavies of Duncan Duck, published at his own expense, who used to travel the tour with a gargantuan, bearded manservant. And Sepp Staffler, a popular Austrian, who plays guitar and sitar and performs nightly at different lounges in Great Gorge, N.J. when he isn’t competing. The ski tour also has its very own George Blanda. That would be blond, wispy Anderl Molterer, the 40-year-old Austrian, long a world class racer and still competitive.

Pro skiing’s immediate success, however, seems to depend on an authentic rivalry building up between Sabich and [Billy] Kidd, who are close friends but whose living styles are as diverse as snow and sand. Sabich is freewheeling on his skis as well as on tabletops. Kidd is thoughtful, earnest, a perfectionist. Spider has his flying, his motorcycles and drives a Porsche 911-E. Billy paints and now drives a Volvo station wagon. Spider enjoys the man-to-man challenge of the pro circuit. Billy harbors some inner doubts regarding his ability to adapt to it.•

In regards to the Boeing’s misbegotten SST jet which I just mentioned, this 1967 company promotional film was wrong about supersonic travel but right more broadly about the near-term future of commercial aviation.

“The supersonic jet will change everything you know about flying,” 1968:

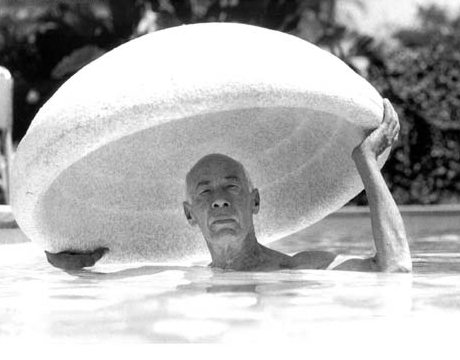

A piece of Henry Miller’s final interview, shortly before his death in 1980.

People aren’t so drawn to Miller because they agree with everything he wrote or did, but because he refused to accept the things handed him that made him unhappy in a time when it was very difficult to say “no.” That’s best expressed in the opening of The Tropic of Capricorn:

“Once you have given up the ghost, everything follows with dead certainty, even in the midst of chaos. From the beginning it was never anything but chaos: it was a fluid which enveloped me, which I breathed in through the gills. In the substrata, where the moon shone steady and opaque, it was smooth and fecundating; above it was a jangle and a discord. In everything I quickly saw the opposite, the contradiction, and between the real and the unreal the irony, the paradox. I was my own worst enemy. There was nothing I wished to do which I could just as well not do. Even as a child, when I lacked for nothing, I wanted to die: I wanted to surrender because I saw no sense in struggling. I felt that nothing would be proved, substantiated, added or subtracted by continuing an existence which I had not asked for. Everybody around me was a failure, or if not a failure, ridiculous. Especially the successful ones. The successful ones bored me to tears. I was sympathetic to a fault, but it was not sympathy that made me so. It was purely negative quality, a weakness which blossomed at the mere sight of human misery. I never helped anyone expecting that it would do me any good; I helped because I was helpless to do otherwise. To want to change the condition of affairs seemed futile to me; nothing would be altered, I was convinced, except by a change of heart, and who could change the hearts of men? Now and then a friend was converted: it was something to make me puke. I had no more need of God than He had of me, and if there were one, I often said to myself, I would meet Him calmly and spit in His face.

What was most annoying was that at first blush people usually took me to be good, to be kind, generous, loyal, faithful. Perhaps I did possess these virtues, but if so it was because I was indifferent: I could afford to be good, kind, generous, loyal, and so forth, since I was free of envy. Envy was the one thing I was never a victim of. I have never envied anybody or anything. On the contrary, I have only felt pity for everybody and everything.

From the very beginning I must have trained myself not to want anything too badly. From the very beginning I was independent, in a false way. I had need of nobody because I wanted to be free, free to do and to give only as my whims dictated. The moment anything was expected or demanded of me I balked. That was the form my independence took. I was corrupt, in other words, corrupt from the start. It’s as though my mother fed me a poison, and though I was weaned young the poison never left my system. Even when she weaned me it seemed that I was completely indifferent; most children rebel, or make a pretence of rebelling, but I didn’t give a damn. I was a philosopher when still in swaddling clothes. I was against life, on principle. What principle? The principle of futility. Everybody around me was struggling. I myself never made an effort. If I appeared to be making an effort it was only to please someone else; at bottom I didn’t give a rap. And if you can tell me why this should have been so I will deny it, because I was born with a cussed streak in me and nothing can eliminate it. I heard later, when I had grown up, that they had a hell of a time bringing me out of the womb. I can understand that perfectly. Why budge? Why come out of a nice warm place, a cosy retreat in which everything is offered you gratis? The earliest remembrance I have is of the cold, the snow and ice in the gutter, the frost on the window panes, the chill of the sweaty green walls in the kitchen. Why do people live in outlandish climates in the temperate zones, as they are miscalled? Because people are naturally idiots, naturally sluggards, naturally cowards. Until I was about ten years old I never realized that there were “warm” countries, places where you didn’t have to sweat for a living, nor shiver and pretend that it was tonic and exhilarating. Wherever there is cold there are people who work themselves to the bone and when they produce young they preach to the young the gospel of work – which is nothing, at bottom, but the doctrine of inertia. My people were entirely Nordic, which is to say idiots. Every wrong idea which has ever been expounded was theirs. Among them was the doctrine of cleanliness, to say nothing of righteousness. They were painfully clean. But inwardly they stank. Never once had they opened the door which leads to the soul; never once did they dream of taking a blind leap into the dark. After dinner the dishes were promptly washed and put in the closet; after the paper was read it was neatly folded and laid away on a shelf; after the clothes were washed they were ironed and folded and then tucked away in the drawers. Everything was for tomorrow, but tomorrow never came. The present was only a bridge and on this bridge they are still groaning, as the world groans, and not one idiot ever thinks of blowing up the bridge.”

Tags: Henry Miller

People in show business are often labeled “genius” if they’re able to complete a sudoku slightly faster than Heidi Klum. But Ricky Jay is the real deal, a deeply brilliant person who can accomplish amazing things with his brain despite the deterioration of some basic neurological functions. A clip of the magician, actor and scholar appearing with Merv Griffin in 1983 and then an excerpt from Mark Singer’s great 1993 New Yorker profile, “Secrets of Magus.”

“Jay has an anomalous memory, extraordinarily retentive but riddled with hard-to-account-for gaps. ‘I’m becoming quite worried about my memory,’ he said not long ago. ‘New information doesn’t stay. I wonder if it’s the NutraSweet.’ As a child, he read avidly and could summon the title and the author of every book that had passed through his hands. Now he gets lost driving in his own neighborhood, where he has lived for several years—he has no idea how many. He once had a summer job tending bar and doing magic at a place called the Royal Palm, in Ithaca, New York. On a bet, he accepted a mnemonic challenge from a group of friendly patrons. A numbered list of a hundred arbitrary objects was drawn up: No. 3 was ‘paintbrush,’ No. 18 was ‘plush ottoman,’ No. 25 was ‘roaring lion,’ and so on. ‘Ricky! Sixty-five!’ someone would demand, and he had ten seconds to respond correctly or lose a buck. He always won, and, to this day, still would. He is capable of leaving the house wearing his suit jacket but forgetting his pants. He can recite verbatim the rapid-fire spiel he delivered a quarter of a century ago, when he was briefly employed as a carnival barker: ‘See the magician; the fire ‘manipulator’; the girl with the yellow e-e-elastic tissue. See Adam and Eve, boy and girl, brother and sister, all in one, one of the world’s three living ‘morphrodites.’ And the e-e-electrode lady . . .’ He can quote verse after verse of nineteenth-century Cockney rhyming slang. He says he cannot remember what age he was when his family moved from Brooklyn to the New Jersey suburbs. He cannot recall the year he entered college or the year he left. ‘If you ask me for specific dates, we’re in trouble,’ he says.”

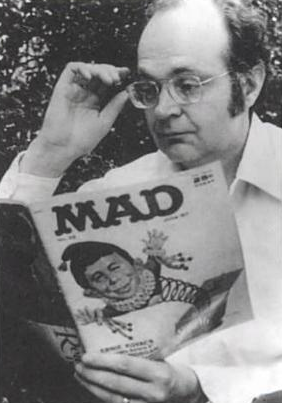

Numbers being crunched is nothing new to sports, as this 1959 video of the Case Institute of Technology basketball team reminds. The assistant coach was an undergraduate computer whiz named Don Knuth who fed data into an IBM 650 to help improve his school’s chances (when he wasn’t busy freelancing for Mad). An excerpt from an interview at computer history.org in which Knuth recalls the first time he saw a computer:

“Later on in my freshman year there arrived a machine that, at first, I could see only through the glass window. They called it a computer. I think it was actually called the IBM 650 ‘Univac.’ That was a funny name, because Univac was a competing brand. One night a guy showed me how it worked, and gave me a chance to look at the manual. It was love at first sight. I could sit all night with that machine and play with it.”

The first post I ever put up on this blog about driverless cars was in 2010. In it, Atari founder Nolan Bushnell was very enthusiastic about “auto-cars,” and I thought it was dubious that American drivers would be willing to give up the wheel in the immediate future.

Anyhow, Bushnell’s legendary gaming company, essentially a ghost brand that’s still alive in the now-adult minds of the children it entertained decades ago, is about to go through its umpteenth attempt at revival. From Nick Wingfield at the New York Times:

“In a phone interview, Mr. [Frédéric] Chesnais said the company was now focusing on mobile and Facebook games, rather than on the far riskier console market, where development budgets are much higher. Atari has announced plans for a social casino game that will exploit vintage Atari games like Asteroids, Centipede and Breakout within slot, poker and blackjack games.

The company intends to enter markets it says are currently underserved by games. In one game under development, Pridefest, players will be able to create their own L.G.B.T. pride parade, designing floats and parade routes. It’s a variation on an existing Atari franchise, RollerCoaster Tycoon, that lets players design amusement parks.

Mr. Chesnais is exploring other, more inchoate concepts. He calls one Atari TV, a plan to produce exclusive video content. The first example is a daily video blog Atari is co-producing called TheRealPelé, which is following the activities of the Brazilian soccer legend in the days leading up to the World Cup in that country.”

______________________________

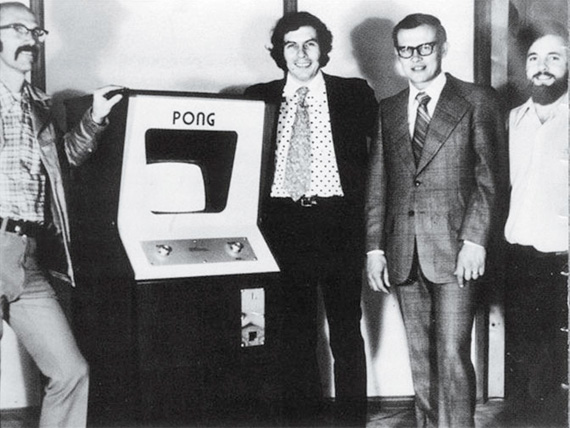

So strange and wonderful: In 1972, Rod Serling introduces I’ve Got a Secret host Steve Allen to the home version of the video game Pong. Begins at the 15:40 mark.

Tags: Frédéric Chesnais, Nick Wingfield

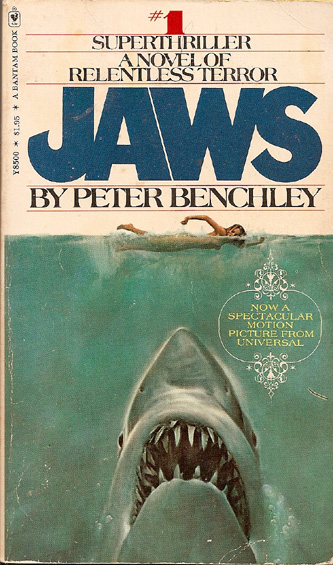

Here’s a rarity: Peter Benchley, author of Jaws, in a part of the preview featurette promoting the novel’s 1975 big-screen Spielberg adaptation, which changed so much about Hollywood filmmaking, pretty much creating the summer blockbuster season. The novelist interviews the director as well as producers Richard Zanuck and David Brown.

Tags: David Brown, Peter Benchley, Richard Zanuck, Steven Spielberg

When the computer is in everything, everything can be hacked. No doubt Google and others are building serious safety features into their driverless-car software because the new vandalism, not to mention terrorism, could be turning an autonomous car the wrong way down a one-way street. From Alex Hern at the Guardian:

“Wil Rockall, a director at KPMG, warns that ‘the industry will need to be very alert to the risk of cyber manipulation and attack.’

‘Self-drive cars will probably work through internet connectivity and, just as large volumes of electronic traffic can be routed to overwhelm websites, the opportunity for self-drive traffic being routed to create ‘spam jams’ or disruption is a very real prospect.’

Rockall suggests that manufacturers could build safety features in to lessen the risk of this happening. ‘The industry takes safety and security incredibly seriously. Doubtless, overrides could be built in so that drivers could shut down many of the car’s capabilities if hacked. That way, humans will still be able to ensure their cars don’t route them on the road to nowhere.’

But Google’s prototype self-driving car, revealed on Tuesday, is largely controlled using an app, and has just two physical buttons: stop, and go. The company has taken a very different approach to firms like Audi and Volvo, who market the driverless features as an addition to, rather than replacement for, a traditional driver.”

_______________________

“Cars without steering wheels,” 1950s:

Tags: Alex Hern, Wil Rockall

This prime 1972 episode of the Mike Douglas Show features John & Yoko as co-hosts. At the 34:20 mark, there’s an appearance by consumer advocate Ralph Nader, who has been right about so many things (airbags, corporate greed, conservation, etc.) and so wrong about one–the 2000 American Presidential election.

This prime 1972 episode of the Mike Douglas Show features John & Yoko as co-hosts. At the 34:20 mark, there’s an appearance by consumer advocate Ralph Nader, who has been right about so many things (airbags, corporate greed, conservation, etc.) and so wrong about one–the 2000 American Presidential election.

There was no difference between the two major-party candidates, Nader said, staying in the race until the end, which turned out to be very bitter for the country. The difference between Dubya and Al Gore was 4,500 U.S. troops dying or not, a 100,000 Iraqis dead or alive, a focus on environmentalism or business as usual as the clock kept running out. For some–perhaps for all–it was the difference between life and death. Adults who can’t see shades of gray always stun me, but it was the same impulses that drove Nader’s righteous career which led him to be the spoiler in 2000.

Tags: John Lennon, Louis Nye, Mike Douglas, Ralph Nader, The Chambers Brothers, Yoko Ono

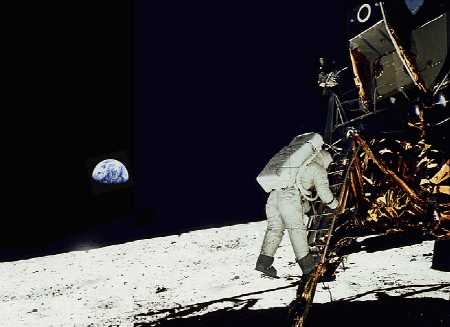

Norman Mailer pursued immortality through subjects as grand as his ego, and it was the Apollo 11 mission that was Moby Dick to his Ahab. He knew the beginning of space voyage was the end, in a sense, of humans, or, at least, of humans believing they were in the driver’s seat. Penguin Classics is republishing his great 1970 writing, Of a Fire on the Moon, 45 years after we touched down up there. Together with Oriana Fallaci’s If The Sun Dies, you have an amazing account of that disorienting moment when technology, that barbarian, truly stormed the gates, as well as a great look at New Journalism’s early peak. Below are some of the posts that I’ve previously put up that refer to Mailer’s book.

_________________________

“It Was Not A Despair He Felt, Or Fear–It Was Anesthesia”

When he wrote about the coming computer revolution of the 1970s at the outset of the decade in Of a Fire on the Moon, Norman Mailer couldn’t have known that the dropouts and the rebels would be leading the charge. An excerpt of his somewhat nightmarish view of our technological future, some parts of which came true and some still in the offing:

“Now they asked him what he thought of the Seventies. He did not know. He thought of the Seventies and a blank like the windowless walls of the computer city came over his vision. When he conducted interviews with himself on the subject it was not a despair he felt, or fear–it was anesthesia. He had no intimations of what was to come, and that was conceivably worse than any sentiment of dread, for a sense of the future, no matter how melancholy, was preferable to none–it spoke of some sense of the continuation in the projects of one’s life. He was adrift. If he tried to conceive of a likely perspective in the decade before him, he saw not one structure to society but two: if the social world did not break down into revolutions and counterrevolutions, into police and military rules of order with sabotage, guerrilla war and enclaves of resistance, if none of this occurred, then there certainly would be a society of reason, but its reason would be the logic of the computer. In that society, legally accepted drugs would become necessary for accelerated cerebration, there would be inchings toward nuclear installation, a monotony of architectures, a pollution of nature which would arouse technologies of decontamination odious as deodorants, and transplanted hearts monitored like spaceships–the patients might be obliged to live in a compound reminiscent of a Mission Control Center where technicians could monitor on consoles the beatings of a thousand transplanted hearts. But in the society of computer-logic, the atmosphere would obviously be plastic, air-conditioned, sealed in bubble-domes below the smog, a prelude to living on space stations. People would die in such societies like fish expiring on a vinyl floor. So of course there would be another society, an irrational society of dropouts, the saintly, the mad, the militant and the young. There the art of the absurd would reign in defiance against the computer.”

_________________________

Some more predictions from Norman Mailer’s 1970 Space Age reportage, Of a Fire on the Moon, which have come to fruition even without the aid of moon crystals:

“Thus the perspective of space factories returning the new imperialists of space a profit was now near to the reach of technology. Forget about diamonds! The value of crystals grown in space was incalculable: gravity would not be pulling on the crystal structure as it grew, so the molecule would line up in lattices free of shift or sheer. Such a perfect latticework would serve to carry messages for a perfect computer. Computers the size of a package of cigarettes would then be able to do the work of present computers the size of a trunk. So the mind could race ahead to see computers programming go-to-school routes in the nose of every kiddie car–the paranoid mind could see crystal transmitters sewn into the rump of ever juvenile delinquent–doubtless, everybody would be easier to monitor. Big Brother could get superseded by Moon Brother–the major monitor of them all might yet be sunk in a shaft on the back face of the lunar sphere.”

_________________________

In his 1970 Apollo 11 account, Of a Fire on the Moon, Norman Mailer realized that his rocket wasn’t the biggest after all, that the mission was a passing of the torch, that technology, an expression of the human mind, had diminished its creators. “Space travel proposed a future world of brains attached to wires,” Mailer wrote, his ego having suffered a TKO. And just as the Space Race ended the greater race began, the one between carbon and silicon, and it’s really just a matter of time before the pace grows too brisk for humans.

Supercomputers will ultimately be a threat to us, but we’re certainly doomed without them, so we have to navigate the future the best we can, even if it’s one not of our control. Gary Marcus addresses this and other issues in his latest New Yorker blog piece, “Why We Should Think About the Threat of Artificial Intelligence.” An excerpt:

“It’s likely that machines will be smarter than us before the end of the century—not just at chess or trivia questions but at just about everything, from mathematics and engineering to science and medicine. There might be a few jobs left for entertainers, writers, and other creative types, but computers will eventually be able to program themselves, absorb vast quantities of new information, and reason in ways that we carbon-based units can only dimly imagine. And they will be able to do it every second of every day, without sleep or coffee breaks.

For some people, that future is a wonderful thing. [Ray] Kurzweil has written about a rapturous singularity in which we merge with machines and upload our souls for immortality; Peter Diamandis has argued that advances in A.I. will be one key to ushering in a new era of ‘abundance,’ with enough food, water, and consumer gadgets for all. Skeptics like Eric Brynjolfsson and I have worried about the consequences of A.I. and robotics for employment. But even if you put aside the sort of worries about what super-advanced A.I. might do to the labor market, there’s another concern, too: that powerful A.I. might threaten us more directly, by battling us for resources.

Most people see that sort of fear as silly science-fiction drivel—the stuff of The Terminator and The Matrix. To the extent that we plan for our medium-term future, we worry about asteroids, the decline of fossil fuels, and global warming, not robots. But a dark new book by James Barrat, Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era, lays out a strong case for why we should be at least a little worried.

Barrat’s core argument, which he borrows from the A.I. researcher Steve Omohundro, is that the drive for self-preservation and resource acquisition may be inherent in all goal-driven systems of a certain degree of intelligence. In Omohundro’s words, ‘if it is smart enough, a robot that is designed to play chess might also want to build a spaceship,’ in order to obtain more resources for whatever goals it might have.”

_________________________

While Apollo 11 traveled to the moon and back in 1969, the astronauts were treated each day to a six-minute newscast from Mission Control about the happenings on Earth. Here’s one that was transcribed in Norman Mailer’s Of a Fire on the Moon, which made space travel seem quaint by comparison:

“Washington UPI: Vice President Spiro T. Agnew has called for putting a man on Mars by the year 2000, but Democratic leaders replied that priority must go to needs on earth…Immigration officials in Nuevo Laredo announced Wednesday that hippies will be refused tourist cards to enter Mexico unless they take a bath and get haircuts…’The greatest adventure in the history of humanity has started,’ declared the French newspaper Le Figaro, which devoted four pages to reports from Cape Kennedy and diagrams of the mission…Hempstead, New York: Joe Namath officially reported to the New York Jets training camp at Hofstra University Wednesday following a closed-door meeting with his teammates over his differences with Pro Football Commissioner Pete Rozelle…London UPI: The House of Lords was assured Wednesday that a major American submarine would not ‘damage or assault’ the Loch Ness monster.”

_________________________

“There Was An Uneasy Silence, An Embarrassed Pall At The Unmentioned Word Of Nazi”

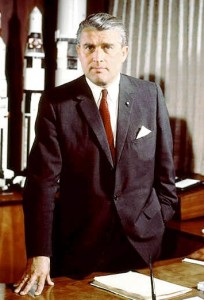

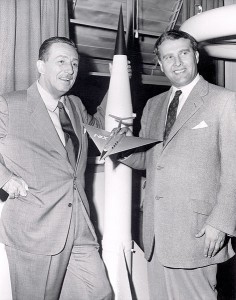

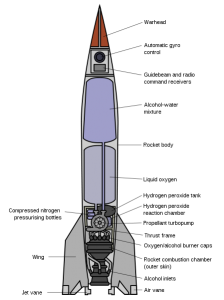

Norman Mailer’s book Of a Fire on the Moon, about American space exploration during the 1960s, was originally published as three long and personal articles for Life magazine in 1969: “A Fire on the Moon,” “The Psychology of Astronauts,” and “A Dream of the Future’s Face.” Mailer used space travel to examine America’s conflicted and tattered existence–and his own as well. In one segment, he reports on a banquet in which Wernher von Braun, the former Nazi rocket engineer who became a guiding light at NASA, meets with American businessmen on the eve of the Apollo 11 launch. An excerpt:

“Therefore, the audience was not to be at ease during his introduction, for the new speaker, who described himself as a ‘backup publisher,’ went into a little too much historical detail. ‘During the Thirties he was employed by the Ordinance Department of the German government developing liquid fuel rockets. During World War II he made very significant developments in rocketry for his government.’

A tension spread in this audience of corporation presidents and high executives, of astronauts, a few at any rate, and their families. There was an uneasy silence, an embarrassed pall at the unmentioned word of Nazi–it was the shoe which did not drop to the floor. So no more than a pitter-patter of clapping was aroused when the speaker went quickly on to say: ‘In 1955 he became an American citizen himself.’ It was only when Von Braun stood up at the end that the mood felt secure enough to shift. A particularly hearty and enthusiastic hand of applause swelled into a standing ovation. Nearly everybody stood up. Aquarius, who finally cast his vote by remaining seated, felt pressure not unrelated to refusing to stand up for The Star-Spangled Banner. It was as if the crowd with true American enthusiasm had finally declared, ‘Ah don’ care if he is some kind of ex-Nazi, he’s a good loyal patriotic American.’

Von Braun was. If patriotism is the ability to improve a nation’s morale, then Von Braun was a patriot. It was plain that some of these corporate executives loved him. In fact, they revered him. He was the high priest of their precise art–manufacture. If many too many an American product was accelerating into shoddy these years since the war, if planned obsolescence had all too often become a euphemism for sloppy workmanship, cynical cost-cutting, swollen advertising budgets, inefficiency and general indifference, then in one place at least, and for certain, America could be proud of a product. It was high as a castle and tooled more finely than the most exquisite watch.

Von Braun was. If patriotism is the ability to improve a nation’s morale, then Von Braun was a patriot. It was plain that some of these corporate executives loved him. In fact, they revered him. He was the high priest of their precise art–manufacture. If many too many an American product was accelerating into shoddy these years since the war, if planned obsolescence had all too often become a euphemism for sloppy workmanship, cynical cost-cutting, swollen advertising budgets, inefficiency and general indifference, then in one place at least, and for certain, America could be proud of a product. It was high as a castle and tooled more finely than the most exquisite watch.

Now the real and true tasty beef of capitalism got up to speak, the grease and guts of it, the veritable brawn, and spoke with fulsome language in his small and well-considered voice. He was with friends on this occasion, and so a savory and gravy of redolence came into his tone, his voice was not unmusical, it had overtones which hinted of angelic super-possibilities one could not otherwise lay on the line. He was when all was said like the head waiter of the largest hofbrau in heaven. ‘Honored guests, ladies and gentlemen,’ Von Braun began, ‘it is with a great deal of respect tonight that I meet you, the leaders, and the captains in the mainstream of American industry and life. Without your success in building and maintaining the economic foundations of this nation, the resources for mounting tomorrow’s expedition to the moon would never have been committed…. Tomorrow’s historic launch belongs to you and to the men and women who sit behind the desks and administer your companies’ activities, to the men who sweep the floor in your office buildings and to every American who walks the street of this productive land. It is an American triumph. Many times I have thanked God for allowing me to be a part of the history that will be made here today and tomorrow and in the next few days. Tonight I want to offer my gratitude to you and all Americans who have created the most fantastically progressive nation yet conceived and developed,’ He went on to talk of space as ‘the key to our future on earth,’ and echoes of his vision drifted through the stale tropical air of a banquet room after coffee–perhaps he was hinting at the discords and nihilism traveling in bands and brigands across the earth. ‘The key to our future on earth. I think we should see clearly from this statement that the Apollo 11 moon trip even from its inception was not intended as a one-time trip that would rest alone on the merits of a single journey. If our intention had been merely to bring back a handful of soil and rocks from the lunar gravel pit and then forget the whole thing’–he spoke almost with contempt of the meager resources of the moon–‘we would certainly be history’s biggest fools. But that is not our intention now–it never will be. What we are seeking in tomorrow’s trip is indeed that key to our future on earth. We are expanding the mind of man. We are extending this God-given brain and these God-given hands to their outermost limits and in so doing all mankind will benefit. All mankind will reap the harvest…. What we will have attained when Neil Armstrong steps down upon the moon is a completely new step in the evolution of man.'”

_________________________

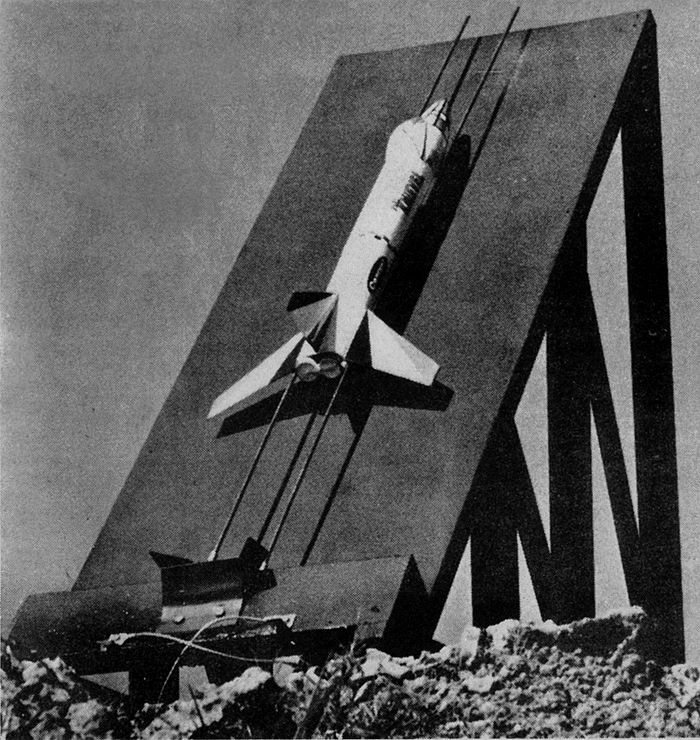

Wernher von Braun inducted into the Space Camp Hall of Fame:

Tom Lehrer eviscerates Wernher von Braun in under 90 seconds:

Tags: Norman Mailer

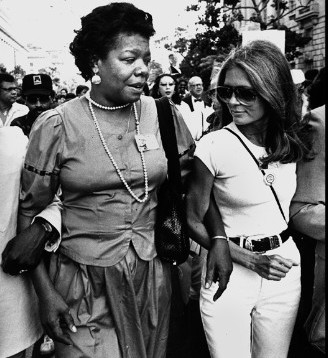

Maya Angelou, who sadly has just passed away, appearing with Merv Griffin in 1982, voicing her concerns about the beginning of what she believed was a politicized class war on less-fortunate Americans, of Reaganomics trying to undo the gains of the New Deal and the Great Society.

Tags: Maya Angelou, Merv Griffin, Ronald Reagan

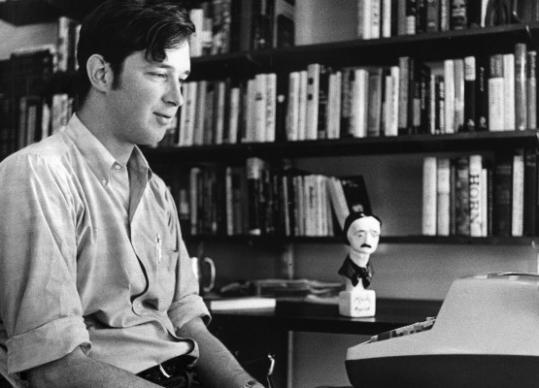

Michael Crichton pushed his book Electronic Life: How To Think About Computers while visiting Merv Griffin in 1983. The personal computing revolution was upon us, but the Macintosh had yet to reach the market, so it still seemed so far away, especially to the tech-challenged host.

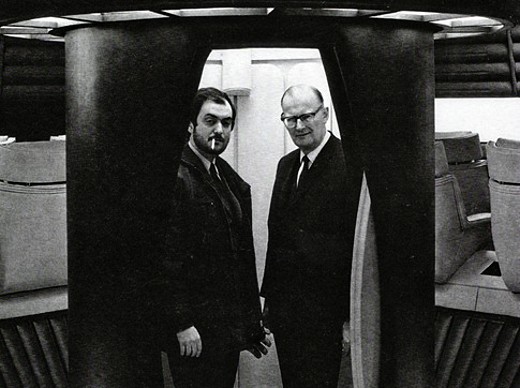

A great 1963 episode of The Sky at Night featuring Arthur C. Clarke, who guessed the timeline of the U.S. moon landing almost exactly but was wrong to think the Russians would get there first. We’re still waiting for those domed bases on the moon and Mars shown on this program.

Tags: Arrhur C. Clarke, Patrick Moore

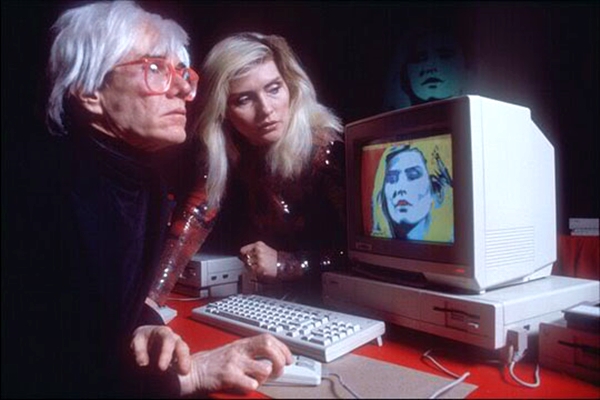

Valerie Solanas was apparently never told that you don’t shoot the messenger. I was completely unaware until watching this video that she shot Andy Warhol the day before Sirhan Sirhan assassinated RFK. In the clip, Warhol and Candy Darling, who, it is written, came from out on the Island, preen for friends and media on a docked boat chartered by Jane Fonda. The line about Warhol’s Superstars “almost living” is striking. Isn’t that what we all dedicate a good portion of our lives to now, with our icons and our selfies and our reality stars? It’s great that everything is freer, but isn’t it surprising what we’ve done with the freedom, the endless channels? It’s life, yes, and it’s almost life.

Tags: Andy Warhol, Brigid Berlin, Brigid Polk, Candy Darling, Jane Fonda

Two pieces of 1970s propaganda for Libertarianism, an -ism I find perplexing.

A clip from the 1978 short, “Libra,” which imagined a 21st-century Libertarian space utopia, population 10,000, including its market-loving African-American leader. Um, wow.

This special version of 1975 film adaptation, The Incredible Bread Machine, is introduced by then-Secretary of the Treasury, William E. Simon, and features commentary by Milton Friedman and some of the book and film’s creators.

A really strange artifact, this 30-minute documentary directed by Theo Kamecke attempted to make Libertarianism sexy. The film’s writers (who appear onscreen as themselves) are six young, long-haired, hip proponents of the philosophy whose very presence sends the message that youth culture and free markets are not mutually exclusive. An incredible oversimplification of complex political and economic issues, the film contains the type of jaw-dropping anti-government propaganda that would give Ayn Rand a huge boner. But it’s still an odd and interesting remnant.

Tags: Milton Friedman, William E. Simon

In 1977, Iggy Pop, not at his absolute healthiest, getting mad on a talk show about some jibber jabber.

Tags: Iggy Pop

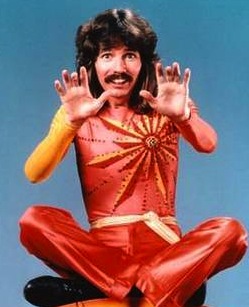

When a kid, I had a seemingly a priori dislike for two things: religion and magic. Not unrelated, right? Yet, I was still forced to go to church and coerced into a Broadway matinee of The Magic Show starring Doug Henning. Well, it usually starred Henning. The day I attended, the lead was his understudy, some dipstick who donned a Henning-esque wig and facial hair. Even dumber. Anyhow, I thought of it recently because Marc Maron had Ivan Reitman on WTF, and the now-famed Hollywood director discussed his involvement in launching the original version (called Spellbound) in Canada. Howard Shore and Paul Shaffer apparently got their start in show business working for Henning’s north-of-the-border stage shenanigans.

But magic wasn’t enough for Henning. He also founded a political organization, The Natural Law Party, which helped him lose elections very badly in both the UK and Canada. Sometimes democracy works.

Tags: Doug Henning, Howard Shore, Ivan Reitman, Marc Maron, Paul Shaffer