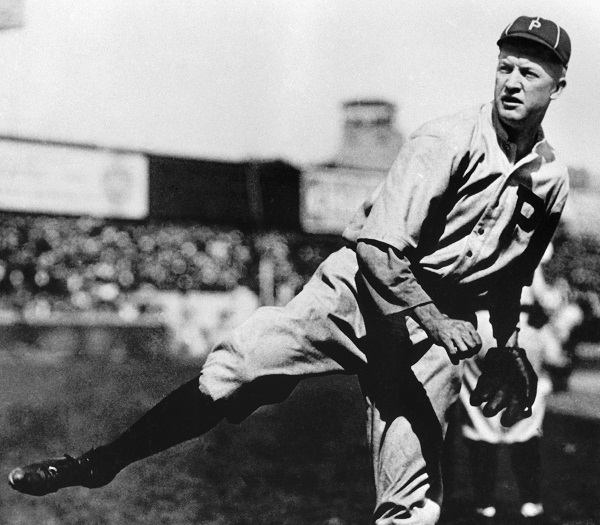

Cameramen swarmed about the great pitcher as he stood there against the green background, both hands holding a baseball above his head as if starting a windup.

“Hold it! Hold it!” they chirped as they focused their cameras.

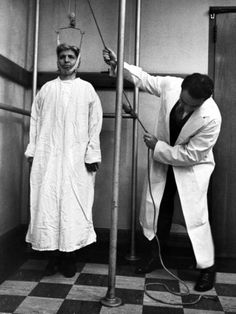

But the pitching immortal couldn’t “hold it.” His arms came down and he almost dropped the ball. He tired that quickly. The great Grover Cleveland Alexander wasn’t weary from pitching a baseball game. He was starting a series of three weeks’ appearances at Hubert’s Dime Museum, on 42nd St., yesterday.

It’s a Different League

This series is in a world far different from the fresh air, sunshine and roaring crowds that the mighty right-hander knew in the old days. And the man is far different too. The posters outside the museum notify passers-by that the “Great Grover Cleveland Alexander” is on exhibition within. But that’s not true. They’re exhibiting only what’s left of the man that was.

The tall man with the dusty brown hair, bulgy waistline, splotched complexion and somewhat bleary eyes is older and more tired now than you would expect of his 51 years. He is weary and bitter. He believes that the game of baseball didn’t do right by him. He feels that the pastime somehow should have warded off the necessity that is sending the great Alexander of Cooperstown’s Baseball Hall of Fame into Hubert’s hall of freaks and flea circuses and dancing girls.

A year ago this month the Baseball Writers of America elected Alexander to the Cooperstown shrine where his name joined those of 13 other immortals. But on this January day the tall man in the wrinkled brown suit stands on a tawdry little stage downstairs in the smoky light and tells how he won the seventh game of the 1926 World Series. How he fanned Tony Lazzeri with the bases loaded and two out.

He gives this little talk twelve times a day, starting at noon and ending at midnight, to earn bread and shelter in this bleak twilight of his life. Between lectures he sits in a little wooden cubicle, below the stage–away from staring eyes. Into this little cubicle come reporters and former players to chat with ‘Ol’ Pete’ and to wonder.

It’s the same platform, cubicle and rigmarole that knew Jack Johnson, the Negro who was former heavyweight champion of the world. That was a year or so ago, when ‘Li’l Arthur’ was hard pressed.

First Time Here Since 1930

“When the museum telegraphed me the offer of a job, I thought somebody was kidding me,” Alexander said. “I hadn’t been in New York since 1930 and I thought a museum was a place where they keep skeletons and things. But, anyway, I took a chance, wired back and got the job.”

A reporter asked why it was that a man with his reputation never was offered a job in major league baseball after his pitching days were over.

“Booze! I used to take a drink now and then when I played. Almost every player drank a bit then, and I guess they still do. But I made the mistake of taking my drinks openly. The word got around that I was a drunkard, which I never was. I believe that’s the reason I never even got a coaching job.”

When Alexander asked managers or owners for work, they told him he hadn’t kept pace with the game and they couldn’t use him because he didn’t know the ‘inside stuff.’

Old Pete laughs bitterly at this when he recalls his 19 years of education in the big time.

“I was in the National League almost 20 years,” he explains, “from 1911 through part of 1930–with the Phillies, Cubs, Cardinals and finally the Phillies again. I know the game inside and out.”

After his retirement in ’30 he managed the House of David team for three seasons. Last year he was out with a semi-pro club in Nebraska, but the going was tough because the farmers had been through a drought.

Despite his bitterness, Alexander seemed to get a thrill out of reliving the old days as he talked to the dime-a-toss listeners.

“I guess my biggest thrill was in the 1926 World Series,” he said. “I was with the Cardinals. We had won three games and the Yanks had won three. Jess Haines started the last game for us and along about the seventh inning he hurt his hand and they told me to go in. There were three on base and Lazzeri was up. I had pitched and won the sixth game the day before, but my arm felt fine. I only threw three times but I struck Tony out. He fouled my second pitch into the left-field stands. Then I threw him a hook and he missed it by about six inches. That proved to be the game and the series.

“Yes, I could strike ’em out in those days. But I kinda struck out myself after I stopped pitchin’.”•