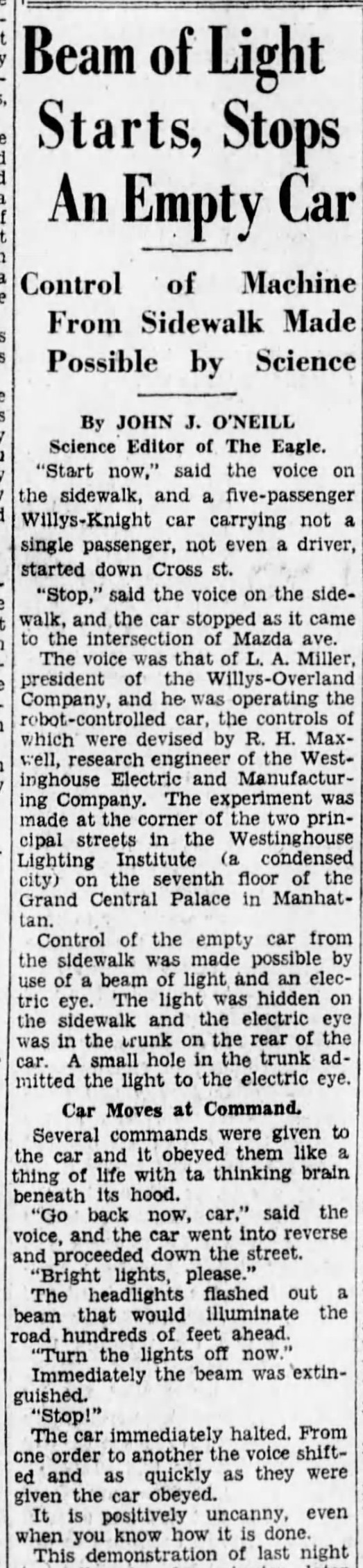

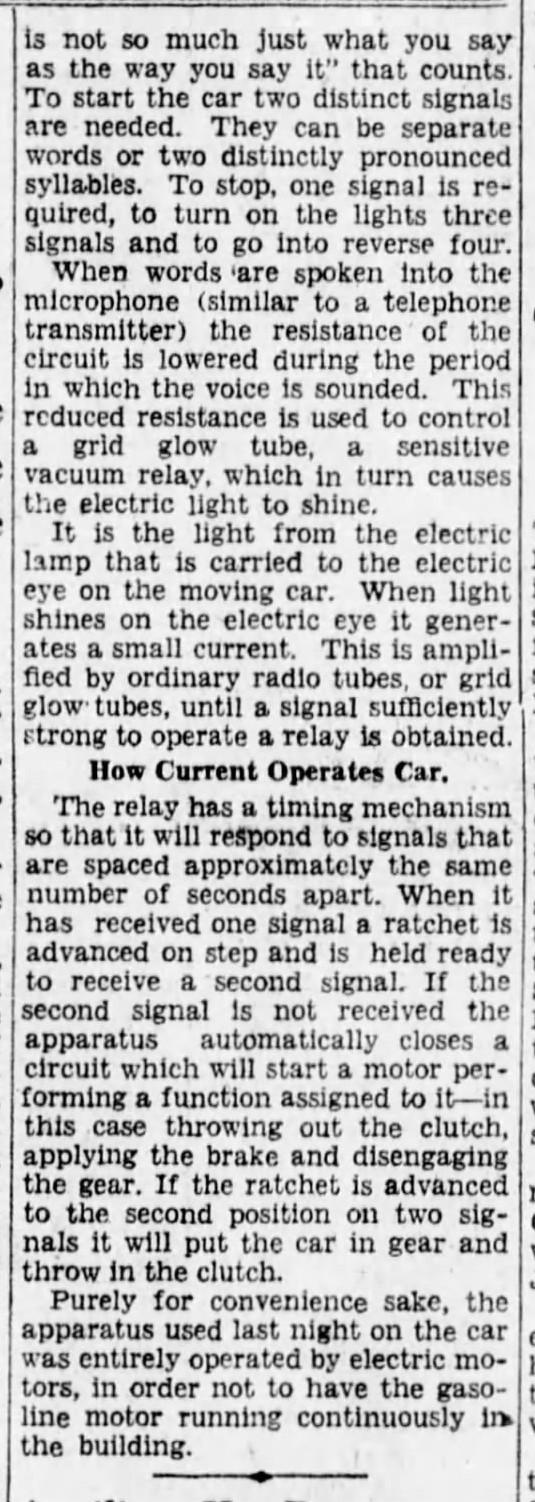

With computers so small they all but disappear, the infrastructure silently becoming more and more automated, what else will vanish from our lives and ourselves? I’m someone who loves the new normal of decentralized, free-flowing media, who thinks the gains are far greater than the losses, but it’s a question worth asking. Via Longreads, an excerpt from The Glass Cage, a new book by that Information Age designated mourner Nicholas Carr:

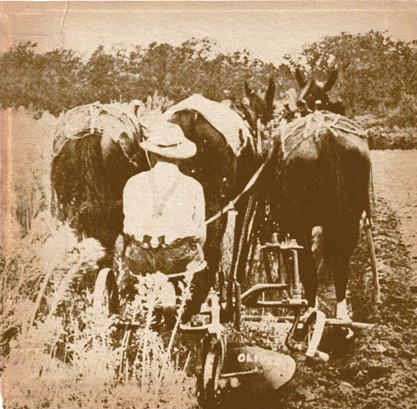

“There’s a big difference between a set of tools and an infrastructure. The Industrial Revolution gained its full force only after its operational assumptions were built into expansive systems and networks. The construction of the railroads in the middle of the nineteenth century enlarged the markets companies could serve, providing the impetus for mechanized mass production. The creation of the electric grid a few decades later opened the way for factory assembly lines and made all sorts of home appliances feasible and affordable. These new networks of transport and power, together with the telegraph, telephone, and broadcasting systems that arose alongside them, gave society a different character. They altered the way people thought about work, entertainment, travel, education, even the organization of communities and families. They transformed the pace and texture of life in ways that went well beyond what steam-powered factory machines had done.

The historian Thomas Hughes, in reviewing the arrival of the electric grid in his book Networks of Power, described how first the engineering culture, then the business culture, and finally the general culture shaped themselves to the new system. ‘Men and institutions developed characteristics that suited them to the characteristics of the technology,’ he wrote. ‘And the systematic interaction of men, ideas, and institutions, both technical and nontechnical, led to the development of a supersystem—a sociotechnical one—with mass movement and direction.’ It was at this point that what Hughes termed ‘technological momentum’ took hold, both for the power industry and for the modes of production and living it supported. ‘The universal system gathered a conservative momentum. Its growth generally was steady, and change became a diversification of function.’ Progress had found its groove.

We’ve reached a similar juncture in the history of automation. Society is adapting to the universal computing infrastructure—more quickly than it adapted to the electric grid—and a new status quo is taking shape. …

The science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke once asked, ‘Can the synthesis of man and machine ever be stable, or will the purely organic component become such a hindrance that it has to be discarded?’ In the business world at least, no stability in the division of work between human and computer seems in the offing. The prevailing methods of computerized communication and coordination pretty much ensure that the role of people will go on shrinking. We’ve designed a system that discards us. If unemployment worsens in the years ahead, it may be more a result of our new, subterranean infrastructure of automation than of any particular installation of robots in factories or software applications in offices. The robots and applications are the visible flora of automation’s deep, extensive, and invasive root system.”