AI can kill all of you humans, and Sir Clive Sinclair will not give a fig. But until that fine day when we’re eminated by machines even more unfeeling than ourselves, let us meditate for a moment on a product the entrepreneur thrust upon the world in 1985, the Sinclair C5. It was a battery-powered EV tricycle, and it was a gigantic flop, the Edsel of pedal transport, a DeLorean dreamed up without the aid of cocaine courage. Was the vehicle wrong or just the time? From Jack Stewart’s BBC piece “Was the Sinclair C5 30 Years Too Early?“:

The C5 had an almost instant image problem. The press and public saw the C5 less as a new mode of transport, and more as a toy – and an expensive one at that. Yours for only £399 (£1,120), and if you wanted to go uphill, you would have to pedal. But the C5 went from drawing board to prototype without any market research, according to Andrew Marks, who wrote an investigation into the vehicle’s failure for the European Journal of Marketing four years after the C5 was released. Sir Clive believed he could create a market where none had existed before, using changes in legislation that allowed electric pedal vehicles and improving battery technology. But, as Marks argues, the C5 programme seemed to be dictated by the company’s conviction, rather than by public demand.

The C5 was also immediately criticised for its safety, or lack thereof. ‘I don’t like the ideas of driving it in traffic, frankly,’ says [BBC reporter Dick] Oliver in [his] report. The driving position was extremely low, making it effectively invisible to other vehicles. It could also be operated by anyone over 14 years old in the UK, without a license or helmet. Famed racing driver Stirling Moss expressed his concerns too.

‘If people get into it and in any way think that they’re in a car because they’re sitting down, then they’re in trouble.’

Media reviews were also harsh about the range – the battery did not live up to expectations – and there was too much exposure to the elements. In retrospect a January launch in London may not have been the most enticing demonstration to carry out. The poor reception meant orders were minimal, and production ceased around eight months later.•

________________________________

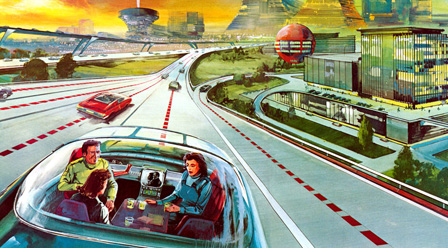

“Imagine a vehicle that can drive you five miles for a penny”: