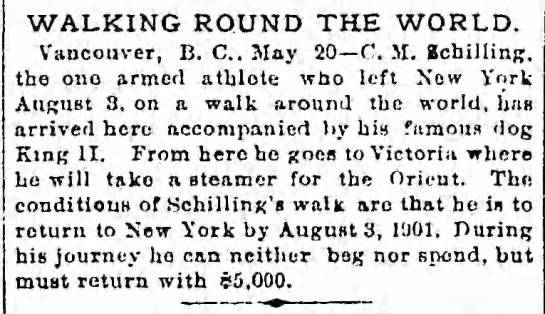

From the March 31, 1903 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

From the March 31, 1903 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

You are currently browsing the archive for the Urban Studies category.

Tags: Tycho Brahe

As drones are set to proliferate, being utilized to photograph and monitor and deliver, it’s worth remembering that kites were formerly dispatched to do some of the same duties, if in a much lower-tech way.

The first use of kites for scientific purposes dates back to 1749 and the meteorological experiments of Alexander Wilson, which occurred three years before Benjamin Franklin’s electrifying discoveries. The use of kites in science received a major boost in the second half of the 19th century, when New York journalist William Abner Eddy designed a superior diamond-shaped kite, which enjoyed improved stability and reached great heights, enabling him to take the first aerial photography in the Western hemisphere. Five years after that feat, in a 1900 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article, Eddy speaks of his plans for his airborne innovations, though the piece was abruptly cut off near the end by typesetters.

Tags: William Abner Eddy

Automobiles remade the world, in more ways than we could have initially imagined. Nobody could have predicted the environmental fallout of the internal-combustion engine, for instance, but other effects could have been predicted by anyone not wholly myopic.

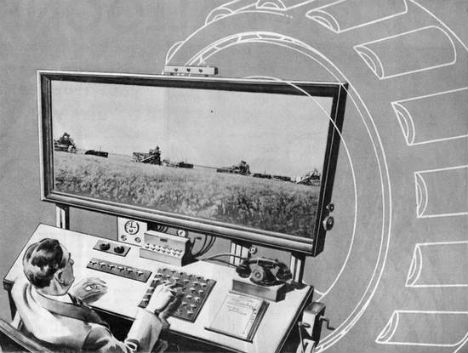

Now we’re parked at another precipice, with autonomous cars nearly ready to remake society in a similarly profound way. Along with the great advantages that will attend self-driving vehicles, there’ll come numerous challenges. One of them is a financial jolt to the middle class that will make the slow waning of the last four decades seem relatively rosy.

In a smart Backchannel article, Robin Chase explains that since driverless is ultimately going to happen–and sooner or later, it will–we need to be proactive in steering the economic and social ramifications even as we give up the actual wheel. Part of her prescription for a relatively smooth transition is a radical reworking of capitalism, since a largely automated society that’s also a free-market one cannot be managed by shopworn policy.

An excerpt:

A Capitalism Do-Over. Productivity gains once were the harbinger of improved standards of living, and improved quality of life, but automation brings jobless productivity gains. Self driving cars will be the ultimate example of this: AVs will probably be productively employed and generating revenue about 65 percent of the time, compared to our personal car’s 5 percent. No one can deny that enormous productivity gains are being enjoyed. But with so few associated workers, enjoyed by whom?

As an entrepreneur, I appreciate the hours and years of effort that has gone into building these AVs: the new IP, the many years and huge costs without any revenue to show for it. But I also understand that this is a massive market (trillions of dollars worldwide seems plausible), and the marginal cost of running the software for each of those trips will be close to zero. We need to make sure we distribute this new wealth, by closing corporate tax loopholes and taxing wealth and platforms more effectively.

As we lose more jobs, the necessity for change opens up the possibility of a fairer system, one that minimizes income inequality. A Bureau of Labor Statistics study projected an 83 percent probability of job loss by automation for workers earning less than $20 an hour, and a 34 percent probability for jobs between $20–40 an hour. In the new automated world, does it really make sense to be taxing labor at all? It makes much more sense to be taxing the new technical platforms that are generating the profits, and taxing the wealth of the small number of talented and lucky people who founded and financed these new jobless wonders.

In a world where machines do most of the work, it is time for a universal basic income. This will distribute the gains from productivity, and give more people the opportunity to focus on purposeful, passion-driven work, allowing for the next generation of ideas and technologies to emerge faster.

How we deal with the job loss caused by AVs will be a signature model for how we respond to automation throughout the economy. Even more, it may be the flood that sweeps clean a system that no longer serves the people.•

Tags: Robin Chase

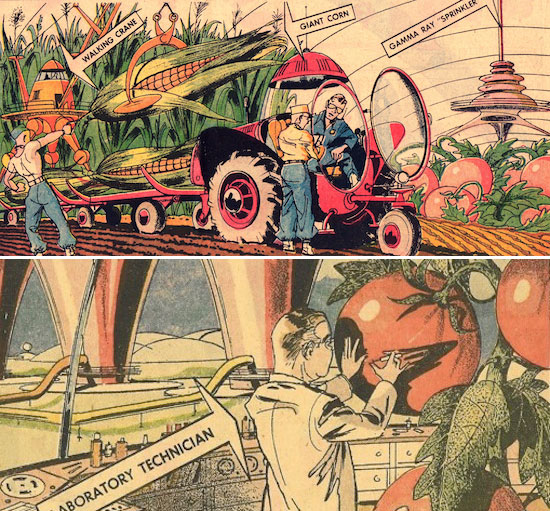

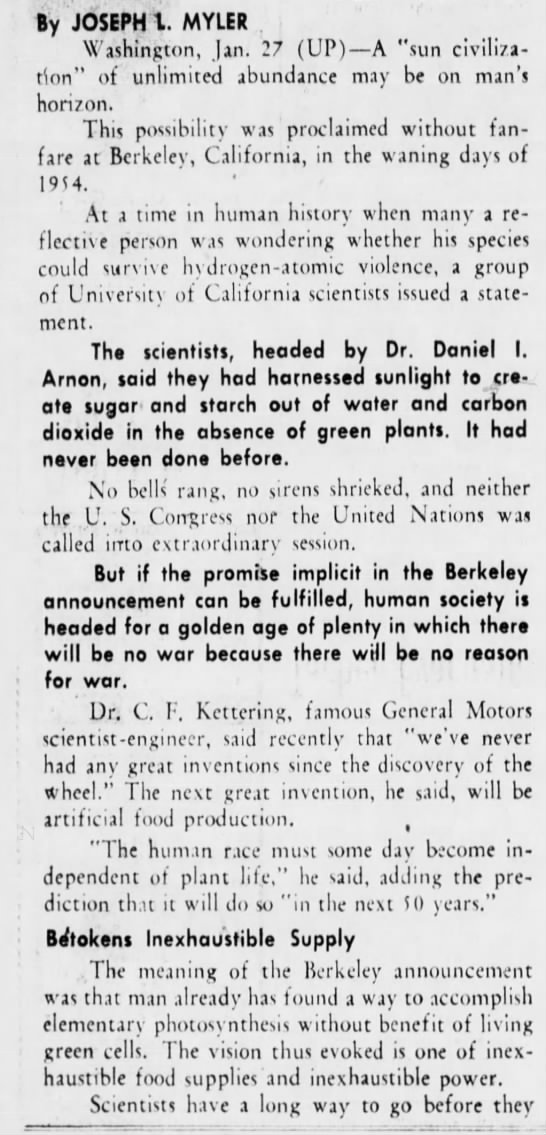

Producing an infinite bounty of healthy food and clean energy through “artificial photosynthesis” was the stated near-term goal of a group of University of California scientists featured in an article in the January 27, 1955 Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Even the dietary needs of space travelers was given consideration.

The rest of us can’t currently afford to live like Vivek Wadhwa, with a Tesla in his garage and solar panels on his roof–not yet, anyway. Today’s tech luxuries often become tomorrow’s new normal, however, the original R&D supported by governments first and then deep-pocketed early adopters. The problem is, while these great inventions will bring with them epic good–maybe even species-saving good–there will be destabilizing effects attending them. Th question is this: How much can we shape the future? How much can we tame these unintended consequences of 3D printers and automation and robotics?

I think we can select to some extent, but in the welter of competing companies and countries, consensus and consent can be lost. If China goes all in on genetic engineering, can other countries afford to opt out? Can there possibly be any OFF switch when the Internet of Things becomes the thing, when we don’t only place a computer in our pocket but have ourselves been placed inside the machine? Some decisions we’ll make and others will be made in a faceless scrum.

From Wadhwa’s latest thoughtful column for the Washington Post:

In short, the distant future is no longer distant. The pace of technological change is rapidly accelerating, and those changes are coming to you very soon, whether you like it or not.

Such rapid, ubiquitous change has, of course, a dark side. Many jobs as we know them will disappear. Our privacy will be further compromised. Future generations may never drive a car or ride in one driven by a human being. We have to worry about biological terrorism and killer drones. Someone you know — maybe you — will have his or her DNA sequence and fingerprints stolen. Man and machine will begin to merge into a single entity. You will have as much food as you can possibly eat, for better and for worse.

The ugly state of politics in the United States and Britain illustrates the impact of income inequality and the widening technological divide. More and more people are being left behind by innovation and they are protesting in every way they can. Technologies such as social media are being used to fan the flames and to exploit ignorance and bias. The situation will get only worse — unless we find ways to share the prosperity we are creating.

We have a choice: to build an amazing future, such as we saw on the TV series Star Trek, or to head into the dystopia of Mad Max.•

Tags: Vivek Wadhwa

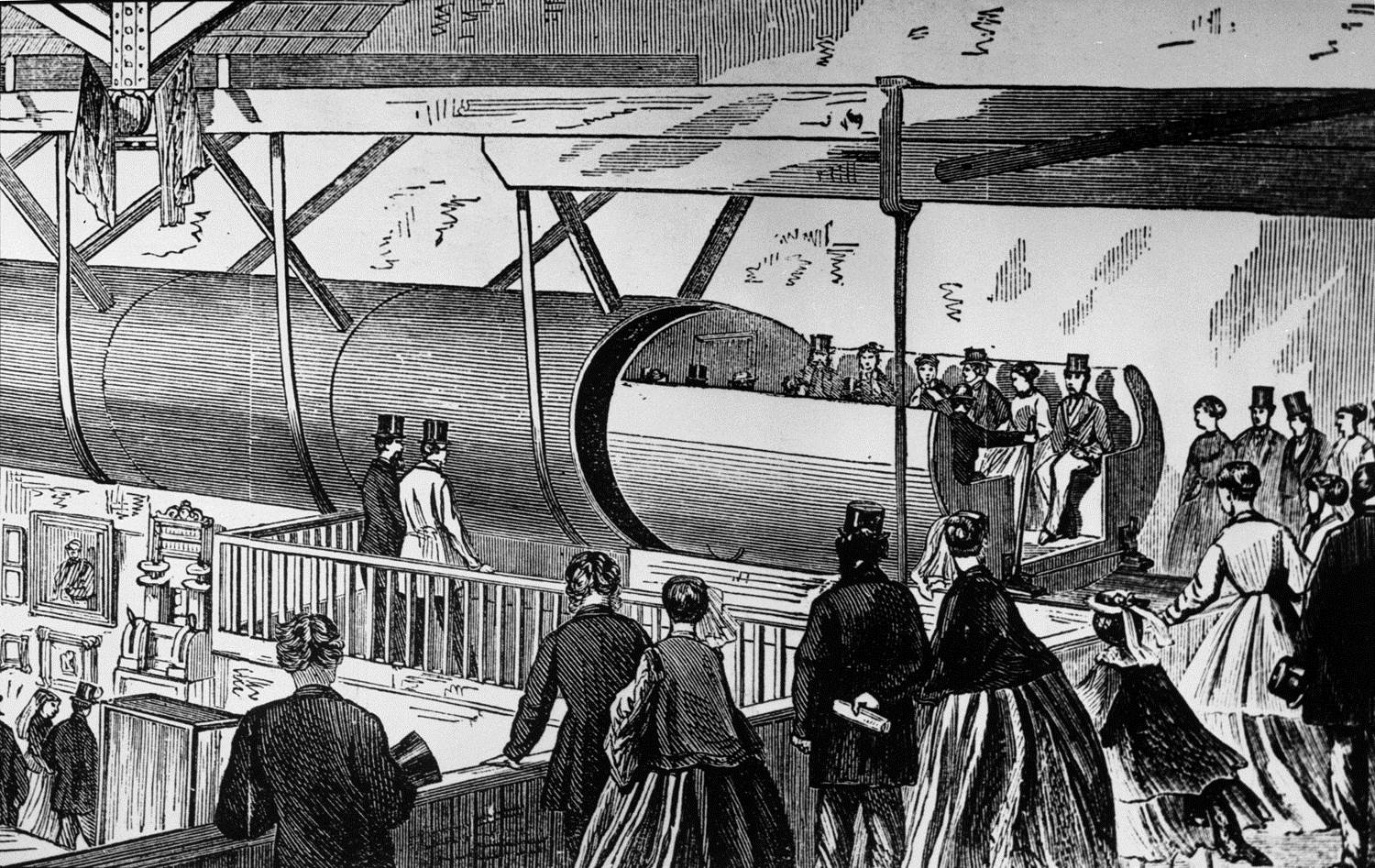

The Internet is a series of tubes that connected the world virtually, while the Hyperloop would like to do so physically. At its grandest, the new mode of transportation proposed by Martian hopeful Elon Musk would complete the Global Village, heaven help us.

Like an incredibly fast elevator that goes forward rather than up, the transport system would deliver people and goods to their destinations in a much safer and cleaner and cheaper fashion, seemingly equally helpful for medium- or long-distance trips. For all the logistical and technological hurdles to be cleared, the future is wide open, though no one can yet say how much the Hypelroop will be a part of it.

The team at Hyperloop One, currently leading the pack in this burgeoning sector, just did an Ask Me Anything at Reddit. A few exchanges follow.

Question:

Where are the efficiency gains over traditional rail or HSR, considering that the Hyperloop needs to maintain pressure, and has more safety concerns? What problem is the Hyperloop trying to solve?

Josh Giegel (Co-founder and President of Engineering):

Efficiency gains come from the fact that this is an on demand system that doesn’t require you to wait and travels at high speeds – think elevator experience. Hyperloop is solving the on demand, high speed, packetized, weather-proof, autonomous system, ultra-safe transport system problem. Low magnetic and aerodynamic drag mean substantially reduced power usage.

Question:

What problems do you foresee, when it comes to convincing the public about the safety of the Hyperloop?

Andrea Vaccaro (Director of Safety Engineering):

We are designing Hyperloop to be the safest mode of transportation on Earth. We will run extensive tests on all the safety features, involving third party safety assessors. As for the public, it will be like the first passenger airplanes: excitement for a new futuristic mode of transportation, together with the extensive safety test that we will run before passenger operation will make people eager to jump on Hyperloop!

Question:

I believe it was philosopher Michel Foucault who suggested that with the introduction of the car, by necessity man had invented the car accident. Likewise, the plane crash wouldn’t have been a thing if there had never been a plane.

If Hyperloop succeeds in creating a new form of transportation, isn’t it inevitable that a new kind of tragedy, heretofore unimaginable to most people, will eventually come to pass?

Andrea Vaccaro:

OK, let’s get a little bit more technical here. First of all by having a fully autonomous mode of transportation, where we are able to fully control the environment, we design-out a lot of common hazards: no human error (by far the most common cause for an accident), at-grade crossing, weather related hazards, etc. Then, we are looking at various statistics (failures per trip, per mile traveled, per departures, etc.) and we are specifying our system to be better than what is currently available from any of these point of view. We are performing top-down hazard analysis and bottom-up failure mode simulations to make sure that we hit our safety targets. Soon we will be start testing our safety functions full-scale in Nevada, with real hardware.

Question:

How do you think your solution will compete with driverless cars since they’re probably gonna hit the market at the same time?

Casey Handmer (Levitation Engineer):

Driverless cars and Hyperloop are complementary mass transportation systems. Cars work on existing transportation infrastructure, while Hyperloop helps integrate larger cities and networks of cities, with new infrastructure development.

Question:

Riding on the Hyperloop – even if its just a test track – is on my bucket list.

What do you think where and when will it be possible to do that without any kind of “special connection” to someone of the team, just by buying a ticket?

Casey Handmer:

We don’t anticipate putting humans on the test track any time soon. Unfortunately, just knowing someone doesn’t mean that we’re any more willing to break our safety protocols ;). But if you come and work here you can probably move stuff in the tube, which is more interesting and has better selfie opportunities. And yes, there are whole varieties of supersonic vacuum tube Pokemon that were previously unknown to science.

Question:

Can you describe how Hyperloop will have an effect on the daily lives of people in 10, 20 and 30 years?

Diana Zhou (Business Analyst):

We’re hoping to transform the way people live, the way they work and play. The idea is that people could hop into a Hyperloop in LA and get to SF for work half an hour later, less than the amount of time it would take to travel from Santa Monica to downtown LA during rush hour right now. This has tremendous implications from a real estate and housing perspective, from a work-life perspective, reduced congestion, not to mention improvement on pollution, emissions, and quality of environment!•

Tags: Andrea Vaccaro, Casey Handmer, Diana Zhou, Josh Giegel

Tags: C.M. Schilling

“He that fights and runs away, may turn and fight another day; But he that is in battle slain, will never rise to fight again,” recorded the Roman historian Tacitus, though the original coiner of the phrase is unknown. It’s another way of saying: Honor is great, but it can get you killed.

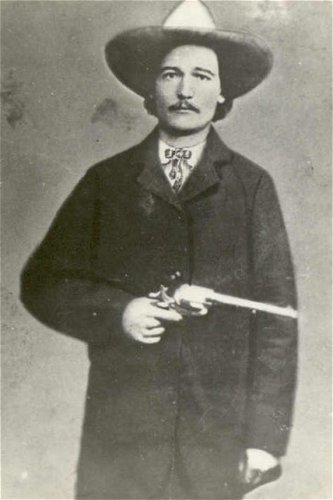

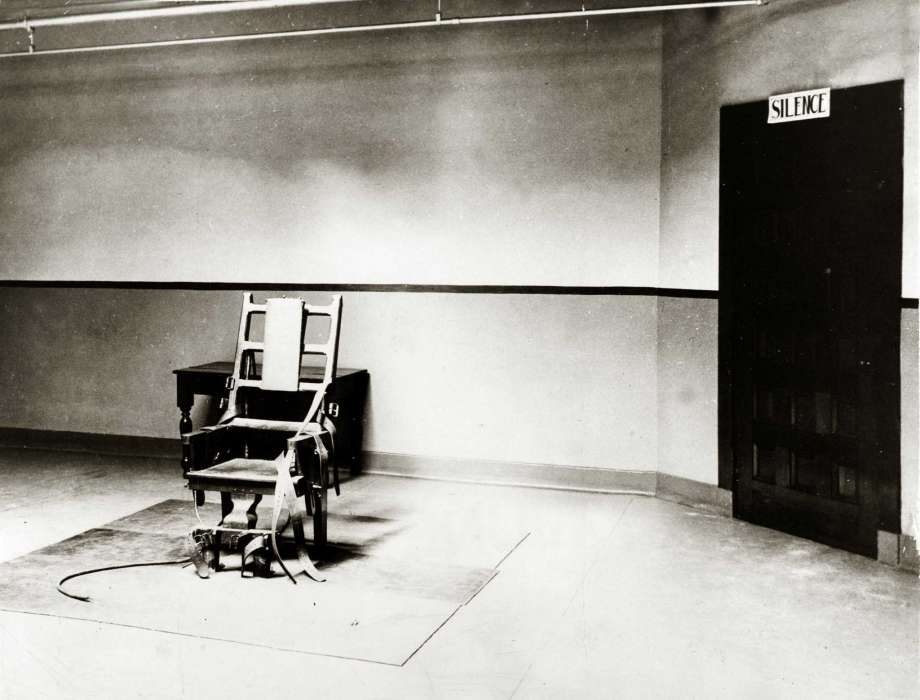

The 1929 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article below records the death of the Creek Nation’s Captain Pleasant Luther “Duke” Berryhill, who somehow balanced the disparate professions of Methodist minister and tribal executioner. He would preach to all who would listen and flog and shoot those who he was ordered to. Berryhill clearly believed in a retributive god.

One interesting note contained in the piece is that those Creeks condemned to die weren’t imprisoned nor were they escorted by authorities to the place of their execution on the fateful day. They were honorable men (and, occasionally, women) and reported dutifully for a bullet to the heart. They probably should have headed for the hills, honor be damned.

George Schuster, driver of the Thomas Flyer that won the New York-to-Paris “Great Race” of 1908, appears on I’ve Got a Secret five decades later. Prior to Schuster’s trek, no “automobilist” had driven across America during the winter. The opening of his 1972 New York Times obituary before the video:

SPRINGVILLE, N. Y., July 4 —George Schuster, who drove a 60‐horsepower Thomas Flyer to victory in the “longest auto race” from New York across America and Siberia to Paris in 1908, died today in a nursing home here. He was 99 years old.

George Schuster, with his grimy, khaki‐clad associates, arrived triumphantly in Paris on a July evening 64 years ago after driving 13,341 miles in 169 days and was promptly flagged down by a gendarme. The offense: driving without lights in the Place de l’Opéra.

But the intrepid round‐the world racers easily surmounted that civilized barrier. The earlier challenges were more ragged —the team had detoured onto the Union Pacific tracks to get across roadless Western Ameri ca, and once even had the San Francisco express bearing down on them; in Asia they had com mandeered 40 Russian soldiers to pull them through the Siberi an muck.

So the impasse in Paris was quickly handled. A French cyclist who had a lantern on his bicycle volunteered to put bike and light into the front seat of the Thomas Flyer and the Americans continued their triumphant parade before enthusiastic crowds.

There were six entries in the race, which started on Lincoln’s Birthday before a huge crowd in Times Square—three French cars and one each from the United States, Italy and Germany.

In a book entitled The Longest Auto Race,which Mr. Schuster wrote with Tom Mahoney in 1966, he recounted highlights of the unprecedented race.

Mr. Schuster, who in the first phases of the race was the mechanic while others in the changing team drove, took over the driving chores after the four ‐ cylinder Flyer had been transported across the Pacific.

In the snowy wastes of the Rocky Mountain region the Union Pacific not only allowed them to use the tracks but also scheduled the Thomas Flyer as if it were a regular train. The only trouble was that the flimsy tires kept blowing out as they bumped along the cross ties, and because of such delays Mr. Schuster and his crew had to set out flares to stop the onrushing San Francisco express.•

If and when driverless cars become the way to travel, whether that day is approaching as fast as Elon Musk thinks or if it’s a further patch down the road, the ramifications will be many. Car ownership won’t be required, nor will it even be necessary for fleets of taxis to be “owned” in any traditional sense. Traffic fatalities will likely plummet, and there should be a salubrious impact on the environment. Of course, the bottom will be pulled out from under the middle class should driving jobs (and all the other enterprises they support) disappear.

Even smaller changes will snake their way through our streets and highways. Case in point: The sun will set on the SUNSET BLVD. street sign and all the rest. Signage won’t be required to direct vehicles and pedestrians provided real-time mapping and augmented reality are adequately developed.

From an Adrienne LaFrance article at the Atlantic:

A map that’s unchanging is actually a map that’s inaccurate. Reality, including the places around us, is always in flux.

Increasingly, digital mobile maps reflect this more liminal state, and—with the help of satellites and GPS and traffic reports and street-level photography—do so with improved precision. (Incidentally, Uber is embarking on its own mapping efforts so it can rely less on Google.) That precision will matter more and more as we head toward a future in which the markings of human-made maps will be read by computers, like the machines that will drive themselves from one place to the next with us sitting inside of them.

And when that happens, the other markers of the old world—like street signs—will eventually disappear. The idea of a city without street signs is a bit startling. Or it was to me, anyway, when my colleague Ian Bogost wrote about it last month. He touched on the same thing that preoccupied the Uber driver I spoke with. Modern maps are free, but they’re enormously valuable.

Google or Apple might restrict access to their mapping services in areas that don’t adopt political positions convenient to their corporate interests. They might even elect to alter the physical environment accordingly. In America, street signs are yoked to signage built for human drivers, mounted atop traffic signals and stop signs. Once those devices aren’t needed, their attached markings might also disappear. Perhaps tech giants could persuade municipalities to remove street signs and markers to realize cleaner, less distracting urban conveyance via the synergy of app-street-and-car transit networks.

It’s jarring to imagine a physical world stripped of these familiar markers, but street signs have already changed dramatically since the early mile markers that dotted the roads of ancient Rome.•

Tags: Adrienne LaFrance

Mentioned a couple days back that Donald Trump’s gross adoration of Vladimir Putin and other autocrats recalls similar warm feelings some American oligarchs felt for Fascists during the 1930s. In an impassioned Guardian essay, Paul Mason, who believes we may soon find ourselves post-capitalism, compares the gathering clouds of that earlier decade to our own WTF moment, with the ugly political rise of the hideous hotelier clearly not an isolated case of extremism.

Mason concludes history isn’t exactly repeating itself, that we’re better off today in our globalized system, save one toxic sticking point, that “an entire generation of humanity has been brutalized.” The writer points to ISIS slayings and minority scapegoating and racist social-media trolling to support his point that we’re worse in this important way eighty years on. Perhaps, but I’m not wholly convinced. Antisemitism in Europe in the first few decades of the 20th century was deeply pernicious and the Jim Crow South was far more heinous than anything that exists in contemporary America, for all our continued instances of racial injustice.

The best argument in favor of our destabilized media, that communication breakdown, is our unmatched access to answer these outrages, to organize against them. There have never been more ways for people of good conscience to refuse to remain silent. Mason is aware of this, acknowledging “we have billions of educated and literate brains on the planet; and we have the concept of universal and inalienable human rights.”

His opening:

Things are happening with machine-gun rapidity: Brexit, the Turkish coup, Islamist massacres in France, the surrounding of Aleppo, the nomination of Donald Trump. From the USA to France to post-Brexit Britain, the high levels of public racism and xenophobia, reflected now in the outpourings of politicians with double-digit poll ratings, have got people asking: is it a rerun of the 1930s?

On the face of it, the similarities are real. Britain’s vote to leave the EU parallels its panicked decision to quit the gold standard in September 1931 – the first major country to quit the global economic system. Labour’s incipient split mirrors the one that left the party out of power for 14 years. And of course the economic background – a depression and a banking crisis – has echoes in the present situation.

But a proper study of the 1930s reveals our situation today to be better and more salvageable in many ways, although in one respect worse.•

Tags: Paul Mason

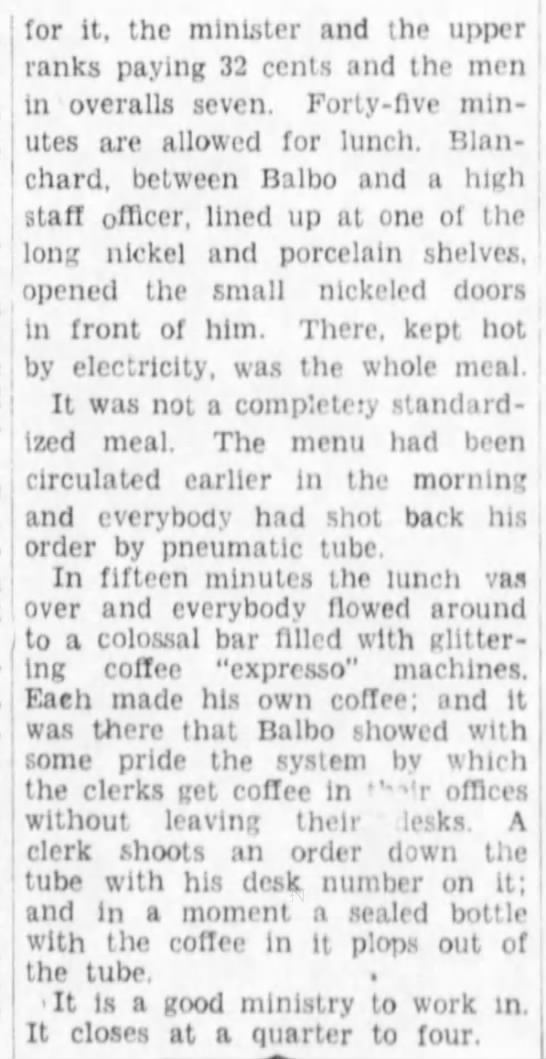

Italo Balbo, Mussolini’s Air Minister, created an experimental office environment that was a technocrat’s dream, humming with gizmos, even if it shared some of the fascist tendencies of his politics. There was an Automat-style lunchroom and a tubing system that delivered coffee to desks, which was wonderful provided you weren’t aging, sickly or disabled. Then you weren’t allowed to work there. There was no opting out of the system, not until Mussolini ultimately met the business end of a meat hook. An article from the February 23, 1933 Brooklyn Daily Eagle reports on Balbo’s “good ministry.”

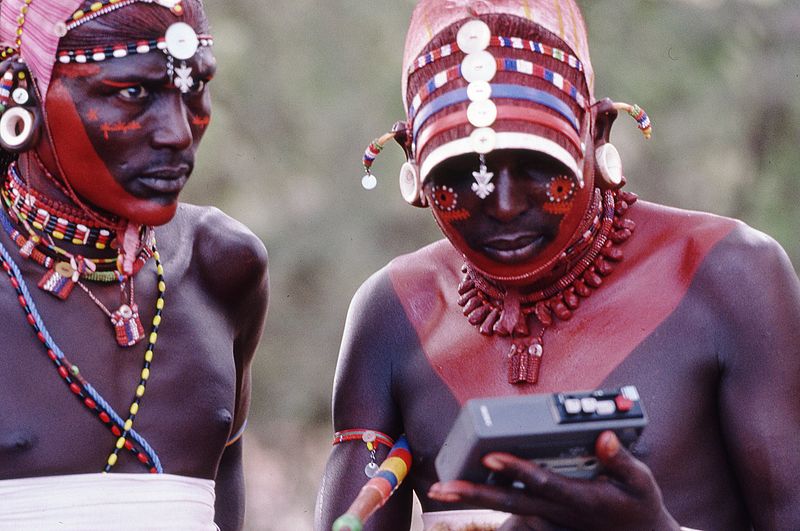

Democracy is only as good as the people, and information is only useful if those crunching the numbers possess sound, critical minds. Smartphones have allowed those in the furthest corners of the globe to have access to an almost unlimited library of ideas and data. How will they use it?

In America and other developed nations, unending streams of info have created a stubbornly chaotic new normal, with conspiracies growing like weeds and democracy coming to seem less like a village than a lynch mob. Will other people, unencumbered by our baggage, manage the modern arrangement in a saner way?

In a Washington Post piece, Caitlin Dewey writes of a recent Reddit Ask Me Anything with members of the Maasai tribe, who are already connected to the rest of us, which might be a blessing. An excerpt:

Earlier this week, Redditors were given a pretty neat opportunity: Two leaders from the Maasai tribe, a seminomadic people living in Western Kenya, signed on to do an “Ask Me Anything.” Redditors asked about the standard stuff: religious practices, diet, what people in the village do for fun. And then, inevitably, one user asked the chiefs to describe their favorite “kind of Internet porn.”

“They don’t believe it and don’t know what it is,” the chiefs’ interlocutor replied — to a giddily gleeful audience. “Don’t think or know about pornography. They are asking is it normal in America.”

The assembled Redditors went wild. It was their crowning achievement. They concluded that they had, in what may have been the Redditiest moment ever Reddited, introduced the concept of Internet porn to a culture that had not encountered it.

But what actually happened is slightly more complicated … and truthfully, more fascinating. Chief Joseph and Assistant Chief Leshan had, in fact, seen Internet porn before, because data-enabled mobile phones have actually become a huge part of even their remote, disconnected community.

As distant as the Maasai may seem from the modern world — the tribe has access to neither running water nor electricity, and many of the questions in the AMA centered on customs like drinking goats’ blood and circumcision without anesthetics — they do increasingly have access to forums like Reddit.

As Adam Schiller, the 24-year-old volunteer who set up the AMA, put it: “Imagine having porn before you have power.”•

Tags: Caitlin Dewey

Promises of a robotics revolution in China have been so overheated that there’s a credibility gap, but Saša Petricic of CBC News reports of real progress in what’s likely a necessary transition for the graying nation. Of course, the world isn’t exactly flat, and what’s needed in a state that’s severely restricted childbirth for decades may not be the best thing for other countries. The thing is, if China truly becomes Ground Zero for robots supplanting human labor, such a changeover will soon occur in places where there’s no shortage of people who need jobs. Victories in the macro can be awfully messy in the micro.

An excerpt:

Supply of cheap labour drying up

The industrial robots might also solve a growing problem: China’s dwindling supply of cheap, low-skilled labour. For three decades, that was the magic ingredient that pushed this economy to become the second biggest in the world. Millions of labourers left the countryside and flooded the industrial cities, lifting themselves out of poverty and their children into the middle class.

But now, there aren’t enough of those children. The population is aging. The so-called demographic dividend is fading.

“It’s becoming harder and harder to recruit workers and to keep them,” said Chen. “This work is intense and tiring, so we have to pay people more and more to lure them and keep them.”

The wage in this plant is around $1,200 a month, more than double the average in this region.Young people, especially, are turning away from the tedious, repetitive factory work their parents sought.

And as overall wages have been skyrocketing in China at a rate of 10 per cent a year, the cost of industrial robots has been plummeting. It cost the Ying Ao factory about $4 million to install the nine robots, about the same amount as a year’s worth of salaries for the 256 workers they replaced.

The cost is expected to drop by a further 20 per cent worldwide in the next decade, according to a study by the Boston Consulting Group.

“This is the future of ‘Made in China,'” said Zhang Tao, the deputy manager for intelligent manufacturing in the hub city of Foshan. “I think it may be too optimistic to say robots will replace humans in three years … but you could say there will be much more co-operation.”•

Tags: Saša Petricic

Paddy Chayefsky, that brilliant satirist, offered a spectacular pre-Beale rant on the Mike Douglas Show in 1969. It starts with polite chatter about the success of his script for Marty but quickly transitions into a much more serious and futuristic discussion. The writer is full of doom and gloom, of course, during the tumult of the Vietnam Era; his best-case scenario for humankind to live more peacefully is a computer-friendly “new society” that yields to globalization and technocracy, one in which citizens are merely producers and consumers, free of nationalism and disparate identity. Well, some of that came true. All the while, he wears a fun, red lei because one of his fellow guests is Hawaii Five-0 star Jack Lord. Gwen Verdon, Lionel Hampton and Cy Coleman share the panel.

Chayefsky joins the show at the 7:45 mark.

Our visual understanding of prehistoric megafauna and other creatures is aided greatly by the work of Charles R. Knight, the painter who gained nationwide attention beginning in the 1920s for his interpretations of dinosaurs and birds long extinct. He certainly couldn’t work from life or memory or photographs, so he became a hunter of facts, an interviewer of scholars, a measurer of skeletons. For an article in the July 31, 1927 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, reporter Frank J. Costello visited the paleoartist in his Upper West Side Manhattan studio and studied his process. The piece’s opening below.

Capturing greatness is rare enough, recapturing it even more unlikely.

Someday Silicon Valley will also founder, the way former Industrial Era powers Cleveland and Pittsburgh and Detroit did. Clusters built around a narrow type of enterprise almost always do, since specialization can be wonderfully beneficial for a while but has a relatively short shelf life. Once the boom goes bust, bringing it back is almost impossible. Cities like New York that are open for business in a broad way have a better shot at continued prosperity, their fickleness and willingness to constantly tear down an asset.

From the Economist piece “Silicon Valley 1.0“:

Cleveland is a reminder that decline can be as self-sustaining as success. There are three reasons why clusters fail. One is that they over-specialise in products that are later improved elsewhere. Sheffield stuck to steelmaking even as others learned to make it better and cheaper. A second is that they complacently fail to upgrade their productivity. Detroit succumbed to Japanese carmakers in the 1970s and 1980s because it thought more about providing its cars with ornate fins (and its workers with gold-plated benefits) than it did about their performance. The third is that they suffer from an external shock from which they fail to recover, as could be the case with the City of London in the wake of Brexit.

Naomi Lamoreaux, an economic historian at Yale University, says Cleveland falls into the third category. It led in a wide variety of industries into the 1920s, including cars, chemicals, paints and varnishes, machine tools and electrical machinery as well as iron and steel. It spent money on R&D. But then came a series of external shocks. The Depression destroyed the local financial institutions that had supported Cleveland’s start-ups. Regulations adopted in its wake gave New York’s banks such a competitive advantage that local capital markets withered. The federal government’s wartime policy of dispersing manufacturing industry eroded the city’s industrial base.

Fanning the flames of hate

Cleveland’s decline became self-reinforcing. Firms downsized, closed or relocated. The inner city fell prey to crime and dysfunction. The white middle-class moved to suburbia. Politicians responded not with pragmatic ideas for reform but by whipping up anger and resentment, which only hastened white- and business-flight. Dennis Kucinich, the mayor in 1977-79, who much later ran for president, refused to privatise the electric utility and, in 1978, took the city into bankruptcy. A once-proud city was mocked as “the mistake on the lake”. To cap it all, Cleveland paid the price for its earlier successes: by 1969 the Cuyahoga River was so polluted that it caught fire, an event that is still celebrated in one of its local brews, Burning River Pale Ale.

The city’s story is also a warning that rebuilding clusters is fiendishly hard.•

The writer Calum Chace, an all-around interesting thinker, is conducting a Reddit AMA based on his new book, The Economic Singularity, which sees a future–and not such a far-flung one–when human labor is a thing of the past. It’s certainly possible since constantly improving technology could make fleets of cars driverless and factories workerless. In fact, there’s no reason why they can’t also be ownerless.

What happens then? How do we reconcile a free-market society with an automated one? In the long run, it could be a great victory for humanity, but getting from here to there will be bumpy. A few exchanges follow.

Question:

So it seems to me that most of the benefit of capitalism for working-class people come from jobs. Companies need a workforce, and are willing to pay for it. So a lot of the profit gets spread around to a lot of people.

If a few companies could break this model on a large scale, by leveraging automation to allow a relatively small core group of employees to operate a national or international corporation, then that would force everyone to do it in order to stay competitive.

I’m assuming that this is some of what you’re talking about in the book (just guessing from the title and an amazon summary).

I could see the first fully (>98%) automated company making waves in a decade or two. People on /r/futorology like to wax utopian, but a company with <100 employees and billions in automated infrastructure isn’t going to allow themselves to be operated for the public good. The product might be cheap, but it’s not free, and that company is no longer employing enough people to matter.

They’ll have a global reach (through subcontracted shipping companies) coupled with automated vehicles that don’t need to sleep or visit family. They can legally exist in whichever country is cheapest tax-wise, and still destroy the competition on the other side of the globe.

So, lots of rambling. But that’s my question, basically.In your opinion, what might the replacement for capitalism look like?

Calum Chace:

Yes, I think you’ve identified exactly the first stage of the argument. Intelligent machines are probably going to render most of us unemployable.

So how shall we all live? The answer, initially at least, will be some form of Universal Basic Income (UBI) which is often discussed here and at a sister Reddit page specifically on the subject. UBI will have to be paid for by taxes, and that raises some tricky questions about how the rich people who pay the taxes are going to respond.

I am fundamentally optimistic. The people who are going to be richest are those who own the AI, since that will generate much of the value throughout the economy. The likes of Larry Page, Sergei Brin, Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates etc etc don’t seem to me to be primarily motivated by money, but by an excitement about the future and a desire to see it arrive sooner.

So I don’t think they will want the rest of us to starve. The mechanism by which UBI is phased in, and how it pans out across international boundaries are going to take a lot of detailed planning. Which we haven’t started yet.

Question:

I also think people are underestimating VR & crowdsourcing’s role.

If VR makes things like microtasking more attractive to do and enables the microtaskers (crowd-workers) to do more, then flexwork/ gig-work might become even more popular. I have an ebook that I’m finishing up now that explores this a little bit (& even ties it to robotics).

Do you have any guesses for VR and the future of work?

Calum Chace:

Yes, I talk about the gig economy (microtasking) in my book. A report by PwC says that 7% of US adults are already engaged in it. I’m not sure whether the experience is so great for most of them at the moment, though. Are they “micro-entrepreneurs” or “instaserfs” – members of a new “precariat”? Either way, it will probably get bigger.

It’s hard to avoid waxing lyrical about the potential impact of VR. Oculus Rift has made nothing like the splash since its launch this year a lot of people (including me) expected it to, but it’s probably just obeying Amara’s Law, that we tend to over-estimate the effect of a technology in the short run and under-estimate the effect in the long run.

In that long run I can well imagine VR bringing about the long-awaited death of geography, but it’s probably going to take a while yet. Meanwhile, I’m not sure it will have that much impact on overall levels of employment, other than adding some because of all the virtual experiences that need to be created.

Question:

I think the outcome can be wonderful: a world of radical abundance.

Calum Chace:

I very much agree with you there, I think that all (7 billion + of us globally) are going to be vastly richer from all of this.

For example, when AI can administer the expertise of top doctors & consultants to everyone on the planet for pennies, this is wealth unlike humanity has ever known before.

I wonder though, on the road to this future, are we in for some quite chaotic breaks from the past.

Exactly, and the sooner we start thinking seriously about where we want to get to and how best to get there, the more likely we are to make the journey successfully.

I think the more people who are aware of what is coming, the better. I’m encouraged by the remarkable sea-change in awareness of AI progress that has already occurred. The publication of Bostrom’s Superintelligence led to high-profile comments by the three wise men (Hawking, Musk and Gates) and the publication of Ford’s Rise of the Robots was another seminal moment.

Like a lot of people here, I’ve been talking about the huge importance of AI to anyone who would listen for years and years. I got a lot of benign virtual pats on the head. Now people are listening.

Self-driving cars will probably be the canary in the coal mine. Once they are common sights, people won’t be able to avoid thinking seriously about what is coming.

But we need a positive narrative about the good things that can happen so that the response isn’t panic, or a rush into the embrace of the next populist demagogue who happens along.•

Tags: Calum Chace

Rob Rhinehart’s Soylent is a tougher sell in developed countries with endless food magazines and cooking shows, though those chugging Red Bulls and wolfing down Devil Dogs shouldn’t look askance at the meal-replacement beverage. The beverage would seem to hold special promise as a sustenance provider in places where scarcity still reigns supreme.

Two excerpts follow from Tom Braithwaite’s smart Financial Times profile of Rhinehart, who somehow manages to live off the grid while living in Los Angeles.

Rhinehart is convinced we will start to abandon three meals a day and instead sip functional foods whenever we need to. “Being wrapped up in breakfast, lunch, dinner came from an agricultural society and the industrial revolution. We don’t work on farms, we don’t work on assembly lines and I don’t think we should eat like we do. I think people will switch to eating when hungry rather than eating on a schedule.”

He stresses this does not mean the end of eating for pleasure. “You get home from work, you’re not in the mood to cook or you’re running out the door in the morning, you don’t have time, but then Friday or Saturday night rolls around and you want to go out with your friends. That’s what I think we’ll move towards.”•

One foot in the future and one foot in the past seems to sum up Rhinehart. His latest project is building a home in Los Angeles, off the grid. This is surprisingly possible in one of the world’s most urban environments. He found disused land in an unfashionable part of town and plonked a shipping container in it, which he now lives in.

This might be eccentric but it’s not a millionaire’s whimsy. The land was cheap because it is not served by electricity or water; the shipping container was $1,500. Rhinehart proudly says he is not wealthy — whatever his paper worth, he draws a fairly modest salary.

“Do you wanna see a picture?” he says, passing me his phone. “The only drawback is the area’s still a little rough, so it got graffitied.”

The container’s power is solar-generated. Of course there is no need for a kitchen. Rhinehart is currently relying on a “Porta Potty” but has hopes for advances in new toilets that vaporise waste. He once tried to save water by taking an antibiotic to minimise trips to the toilet. “I massacred my gut bacteria,” he wrote in his blog.•

Tags: Rob Rhinehart, Tom Braithwaite

Every time I start to criticize Elon Musk, I remember to be thankful he’s not Peter Thiel.

Walter Isaacson famously named Benjamin Franklin when searching for an historical antecedent for Musk, but the Tesla-Space X-Hyperloop-aspiring-Martian billionaire seem to have his heart set on being a multi-planetary Thomas Edison.

In his just-released “Master Plan, Part Deux,” Musk expounds on a vision that would be daunting if it was being attempted by a wonderfully funded Bell Labs or NASA or even a superpower government let alone a struggling private company. The sections on solar roofs and autonomous transport are particularly fascinating.

As Will Oremus writes in a Slate column, one aspect of Musk’s ambitions didn’t make big news despite having world-changing implications. An excerpt:

On Wednesday night, Elon Musk announced a new master plan for his company. It is the philosophical successor to his original master plan, published 10 years ago when few had heard of Tesla and fewer cared. If that first plan seemed implausibly audacious, this one borders on schizophrenic—a compendium of goals so futuristic and disparate that it would be a marvel for any company to achieve one of them, let alone all. They include (deep breath):

- Building at least four all-new models: a “new kind of pickup truck,” a compact SUV, a semi truck, and a bus-like mass transport vehicle that delivers its passengers from door to door. They’ll all be fully electric, of course.

- Developing and implementing a fully autonomous driving system that will require no human involvement. The system will have such redundancy that a failure of any part of the driving system will not compromise its ability to navigate safely.

- Creating a car-sharing platform through which Tesla owners can, at the tap of a button, rent out their self-driving vehicle to a “Tesla shared fleet” when they’re not using it. Others can then summon the car for a ride, generating income for its owner which can help to pay off the price of buying it.

- Merging Tesla and SolarCity, the country’s largest solar power company, and together developing a seamlessly integrated system that can both capture and store solar power on your rooftop, turning your home into its own energy utility. And then “scale that throughout the world.”

Not even cracking the top four objectives in the new plan is Musk’s recently stated intention to essentially reinvent the mass production process, developing a heavily automated factory that can churn out cars five to 10 times more efficiently than before. In other words, Musk writes, Tesla is designing “the machine that makes the machine—turning the factory itself into a product.”•

Tags: Elon Musk, Will Oremus

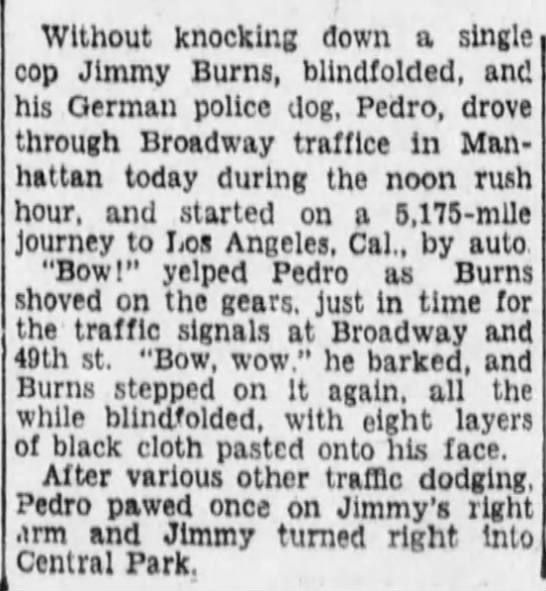

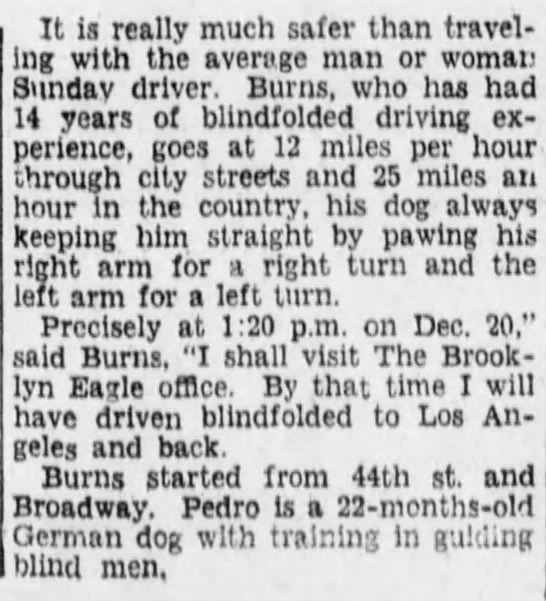

Long before work began in earnest on autonomous cars that wouldn’t require us to keep our eyes on the road, one brave (and incredibly foolish) soul experimented in this area. Even though the headline of this November 5, 1928 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article refers to plural “autoists,” Jimmy Burns is the lone driver named who made cross-country trips blindfolded, guided only by his trusty dog Pedro. No explanation for Burns’ behavior is provided.