In an interview with Seung-yoon Lee of Byline, Noam Chomsky expresses his belief that the foundering of the traditional news and the democratization of the media hasn’t really changed for the better the public dialogue. Perhaps. Income inequality, for instance, has only gotten worse since the media came into the hands of the masses, though that also has to do with myriad other issues. But we won’t be leading the conversation as long as people are satisfied with bread and Kardashians.

As for Chomsky saying he learns about what’s happening in Ukraine or Syria by reading the New York Times, Associated Press and British press rather than by looking at social media and search engines, I would only suggest his news-reading habits are vastly different than the majority. It doesn’t mean he’s wrong, but he’s likely an outlier.

Two exchanges follow, one about the state of modern media and the other about Charlie Hebdo.

____________________________

Seung-yoon Lee:

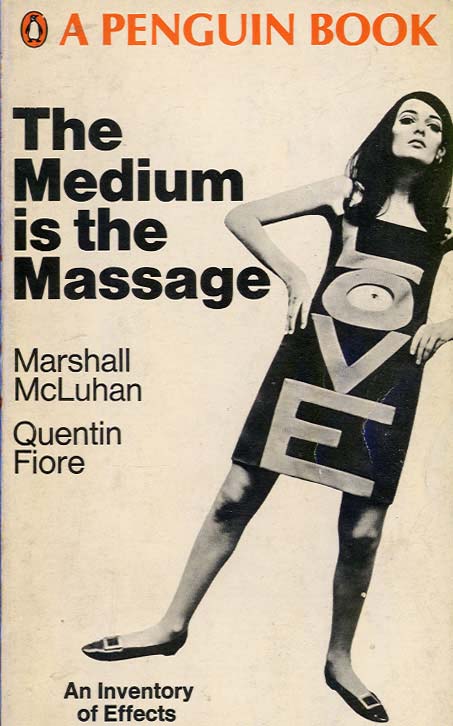

Twenty-seven years ago, you wrote in Manufacturing Consent that the primary role of the mass media in Western democratic societies is to mobilise public support for the elite interests that lead the government and the private sector. However, a lot has happened since then. Most notably, one could argue that the Internet has radically decentralised power and eroded the power of traditional media, and has also given rise to citizen journalism. News from Ferguson, for instance, emerged on Twitter before it was picked up by media organisations. Has the internet made your ‘Propaganda Model’ irrelevant?

Noam Chomsky:

Actually, we have an updated version of the book which appeared about 10 years ago with a preface in which we discuss this question. And I think I can speak for my co-author, you can read the introduction, but we felt that if there have been changes, then this is one of them. There are other [changes], such as the decline in the number of independent print media, which is quite striking.

As far as we can see, the basic analysis is essentially unchanged. It’s true that the internet does provide opportunities that were not easily available before, so instead of having to go to the library to do research, you can just open up your computer. You can certainly release information more easily and also distribute different information from many sources, and that offers opportunities and deficiencies. But fundamentally, the system hasn’t changed very much.

Seuny-yoon Lee:

Emily Bell, Director at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia Journalism School, said the following in her recent speech at Oxford: “News spaces are no longer owned by newsmakers. The press is no longer in charge of the free press and has lost control of the main conduits through which stories reach audiences. The public sphere is now operated by a small number of private companies, based in Silicon Valley.” Nearly all content now is published on social platforms, and it’s not Rupert Murdoch but Google’s Larry Page and Sergei Brin and Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg who have much more say in how news is created and disseminated. Are they “manufacturing consent” like their counterparts in so-called ‘legacy’ media?

Noam Chomsky:

Well, first of all, I don’t agree with the general statement. Say, right now, if I want to find out what’s going on in Ukraine or Syria or Washington, I read the New York Times, other national newspapers, I look at the Associated Press wires, I read the British press, and so on. I don’t look at Twitter because it doesn’t tell me anything. It tells me people’s opinions about lots of things, but very briefly and necessarily superficially, and it doesn’t have the core news. And I think it’s the opposite of what you quoted – the sources of news have become narrower.•

____________________________

Seung-yoon Lee:

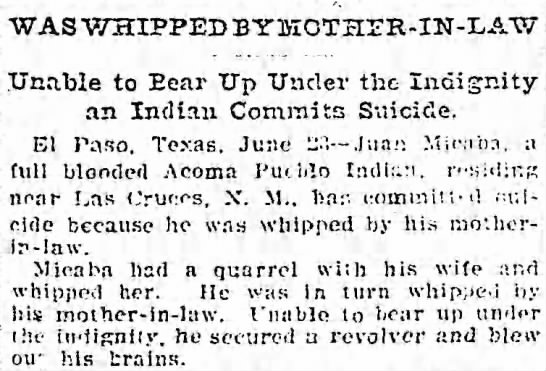

Also, regarding the specific incident of Charlie Hebdo, do you think the cartoonists lacked responsibility?

Noam Chomsky:

Yes, I think they were kind of acting in this case like spoiled adolescents, but that doesn’t justify killing them. I mean, I could say the same about a great deal that appears in the press. I think it’s quite irresponsible often. For example, when the press in the United States and England supported the worst crime of this century, the invasion of Iraq, that was way more irresponsible than what Charlie Hebdo did. It led to the destruction of Iraq and the spread of the sectarian conflict that’s tearing the region to shreds. It was a really major crime. Aggression is the supreme international crime under international law. Insofar as the press supported that, that was deeply irresponsible, but I don’t think the press should be shut down.•