Grantland has many fine writers and reporters, but the twin revelations for me have been Molly Lambert and Alex Pappademas, whom I enjoy reading as much as anyone working at any American publication. The funny thing is, I’m not much into pop culture, which is ostensibly their beat. But as with the best of journalists, the subject they cover most directly is merely an entry into many other ones, long walks that end up in big worlds.

Excerpts follow from a recent piece by each. In “Start-up Costs,” a look at Silicon Valley and Halt and Catch Fire, Pappademas circles back to Douglas Coupland’s 1995 novel, Microserfs, a meditation on the reimagined office space written just before Silicon Valley became fully a brand as well as a land. In Lambert’s “Life Finds a Way,” the release of Jurassic World occasions an exploration of the enduring beauty of decommissioned theme parks–dinosaurs in and of themselves–at the tail end of an entropic state. Both pieces are concerned with an imposition on the natural order of things by capitalism.

_______________________________

From Pappademas:

Microserfs hit stores in 1995, which turned out to be a pretty big year for Net-this and Net-that. Yahoo, Amazon, and Craigslist were founded; Javascript, the MP3 compression standard, cost-per-click and cost-per-impression advertising, the first “wiki” site, and the Internet Explorer browser were introduced. Netscape went public; Bill Gates wrote the infamous “Internet Tidal Wave” memo to Microsoft executives, proclaiming in the course of 5,000-plus words that the Internet was “the most important single development to come along since the IBM PC was introduced in 1981.” Meanwhile, at any time between May and September, you could walk into a multiplex not yet driven out of business by Netflix and watch a futuristic thriller like Hackers or Johnny Mnemonic or Virtuosity or The Net, movies that capitalized on the culture’s tech obsession as if it were a dance craze, spinning (mostly absurd) visions of the (invariably sinister) ways technology would soon pervade our lives. Microserfs isn’t as hysterical as those movies, and its vision of the coming world is much brighter, but in its own way it’s just as wrongheaded and nailed-to-its-context.

“What is the search for the next great compelling application,” Daniel asks at one point, “but a search for the human identity?” Microserfs argues that the entrepreneurial fantasy of ditching a big corporation to work at a cool start-up with your friends can actually be part of that search — that there’s a way to reinvent work in your own image and according to your own values, that you can find the same transcendence within the sphere of commerce that the slackers in Coupland’s own Generation X4 eschewed McJobs in order to chase. The notion that cutting the corporate cord to work for a start-up often just means busting out of a cubicle in order to shackle oneself to a laptop in a slightly funkier room goes unexamined; the possibility that work within a capitalist system, no matter how creative and freeform and unlike what your parents did, might be fundamentally incompatible with self-actualization and spiritual fulfillment is not on the table.•

_______________________________

Lambert’s opening:

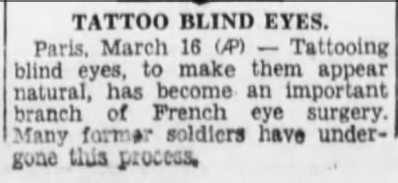

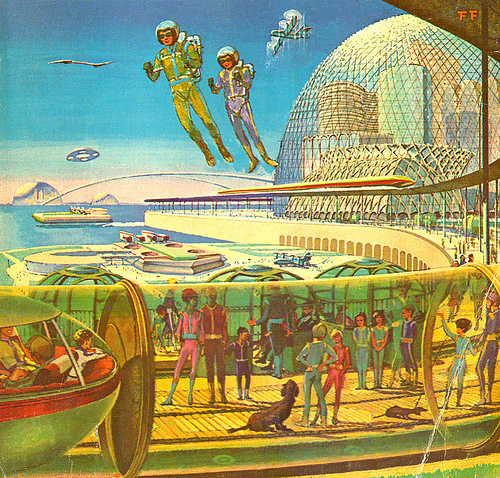

I drove out to the abandoned amusement park originally called Jazzland during a trip to New Orleans earlier this year. Jazzland opened in 2000, was rebranded as Six Flags New Orleans in 2003, and was damaged beyond repair a decade ago by the flooding caused by Hurricane Katrina. But in the years since it’s been closed, it has undergone a rebirth as a filming location. It serves as the setting for the new Jurassic World. As I approached the former Jazzland by car, a large roller coaster arced into view. The park, just off Interstate 10, was built on muddy swampland. I have read accounts on urban exploring websites by people who’ve sneaked into the park that say it’s overrun with alligators and snakes.

After the natural disaster the area wasted no time in returning to its primeval state: a genuine Jurassic World. It was in the Jurassic era when crocodylia became aquatic animals, beginning to resemble the alligators currently populating Jazzland. I saw birds of prey circling over the theme park as I reached the front gates, only to be told in no uncertain terms that the site is closed to outsiders. I pleaded with the security guard that I am a journalist just looking for a location manager to talk to, but was forbidden from driving past the very first entrance into the parking lot. I could see the ticket stands and Ferris wheel, but accepted my fate and drove away, knowing I’d have to wait for Jurassic World to see Jazzland. As I drove off the premises, I could still glimpse the tops of the coasters and Ferris wheel, obscured by trees.

I am fascinated by theme parks that return to nature, since the idea of a theme park is such an imposition on nature to begin with — an obsessively ordered attempt to overrule reality by providing an alternate, superior dimension.•