From “After Catastrophe,” a Scott Carlson article in the Chronicle of Higher Education about the field of Resiliency, which holds that we shouldn’t try to eliminate risk at all costs but instead use resources to manage it better:

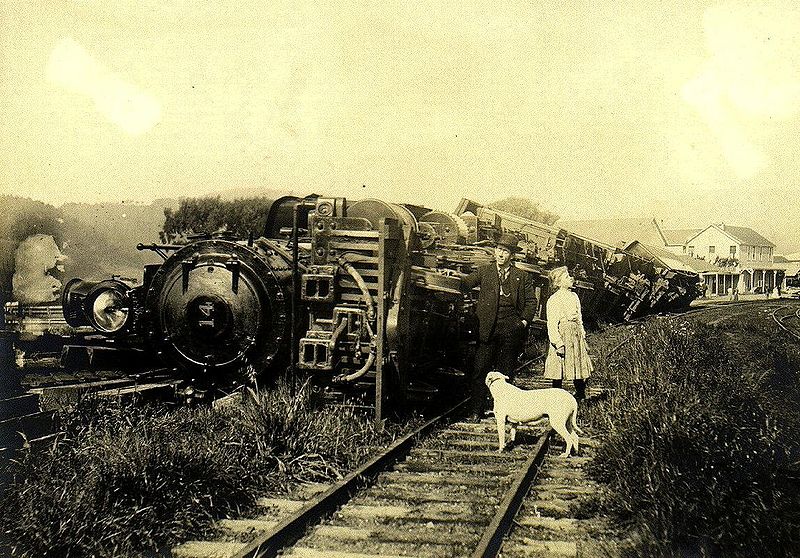

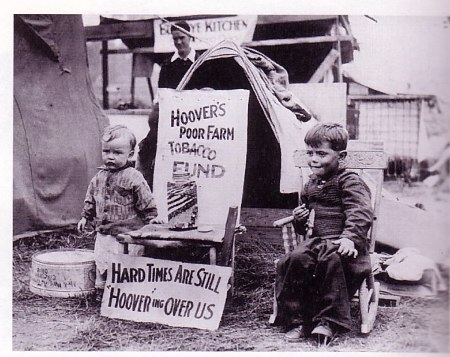

“Consider what has hit us hardest in recent years, how some of these disruptions came from or led to other woes: September 11, 2001; the 2003 Northeast blackout; the oil shock of 2008; the mortgage crisis and the Great Recession; Deepwater Horizon; the intense droughts; Hurricanes Katrina, Irene, and Sandy.

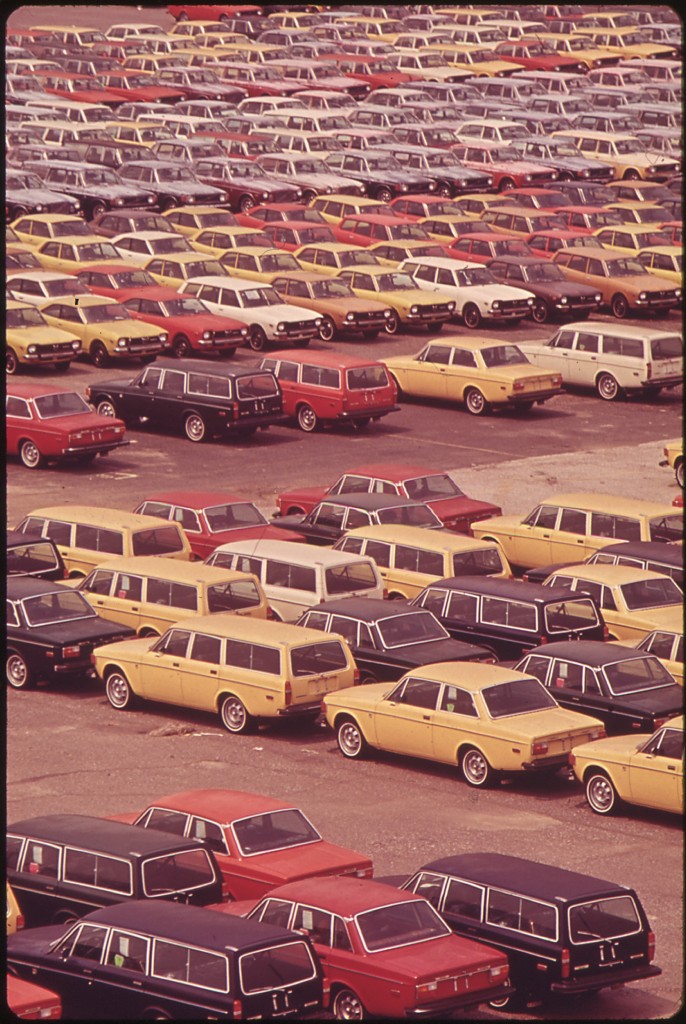

There are surely more disruptions to come. Stephen E. Flynn, a security expert and former military officer who is co-director of the George J. Kostas Research Institute for Homeland Security at Northeastern University, ticks off the most likely threats: a breakdown in the power grid; interruption of global supply chains, including those that provide our food; an accident at one of the many chemical factories in urban areas; or damage to the dams, locks, and waterways that shuttle agricultural products and other goods out to sea. The No. 1 threat, he says, is a terrorist attack that prompts lawmakers and a frightened public to shred the Bill of Rights or overreact in another way.

The tendency in government has been to focus intensely on these threats—or other problems, considering the wars on cancer, poverty, drugs, crime, and so on—and to try to eliminate them.

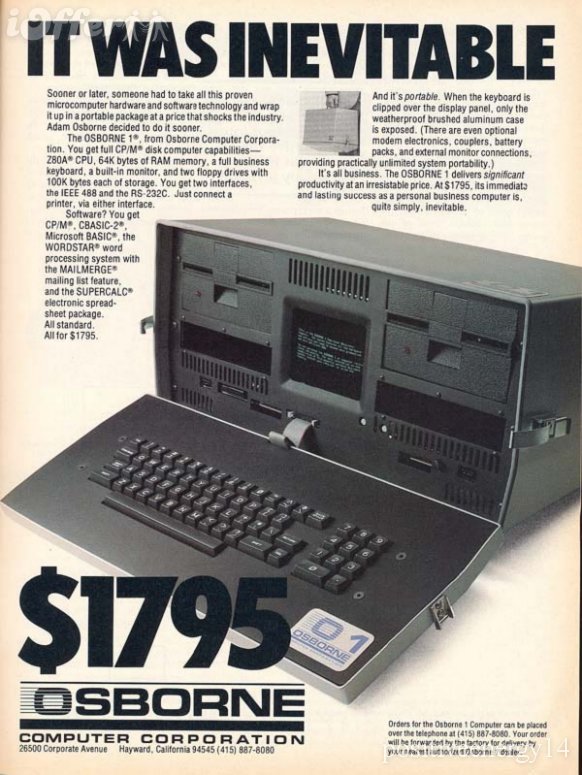

‘If you look at the post-World War II area,’ Flynn says, ‘there is almost an overarching focus on reducing risk and bringing risk down to zero,’ the idea that this could be done ‘if you brought enough science and enough resources and you applied enough muscle.’ Since 9/11, that policy has meant spending vast sums to go after terrorists out there, but perhaps we aren’t safer.

‘Why do we have all this money to go after man-made terrorist attacks, and then we let our bridges fall down?’ Flynn wonders.

He advocates a different approach. We should make American society more robust so that it can absorb shocks and carry on.”