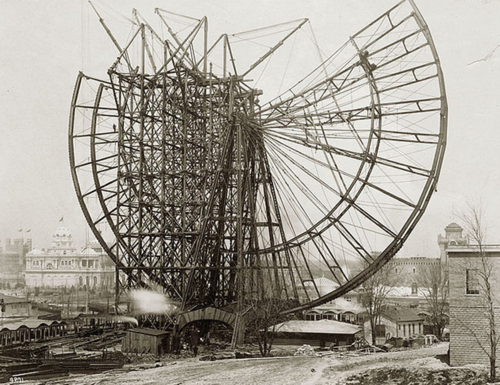

World fairs regularly introduced us to greatness–the telephone, the Ferris wheel, the elevator. But they grew impractical as people became more connected, as the shock of the new came directly to you and I wherever we were. In an Aeon essay, Venkatesh Rao makes a convincing case that Silicon Valley is the new world’s fair, one that never closes. An excerpt about the technological significance of the fairs:

“The history of technology is the story of transitions that worked, like the Industrial Revolution. It entered adolescence and began breaking free of the pre-modern social order at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London. Even as the worldwide mercantilist social order led by Britain began to unravel, the modern industrial social order began to take shape in America.

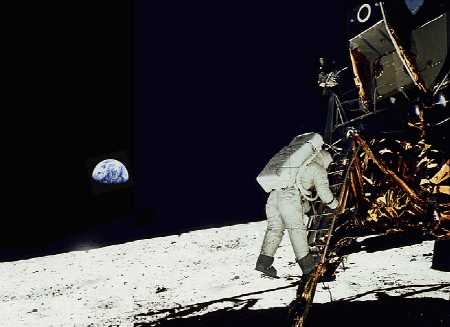

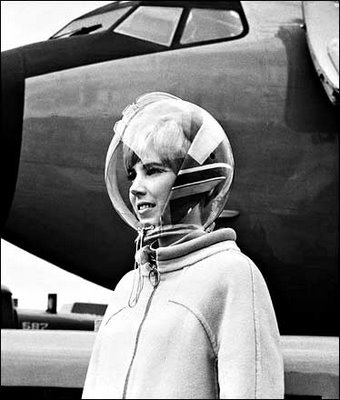

By the time of the 1967 Montreal Expo, the scenes were safely sequestered again within Cold War institutions, after the world had been violently transformed through great wars, thousands of inventions, and a massive reordering of society along urban lines.

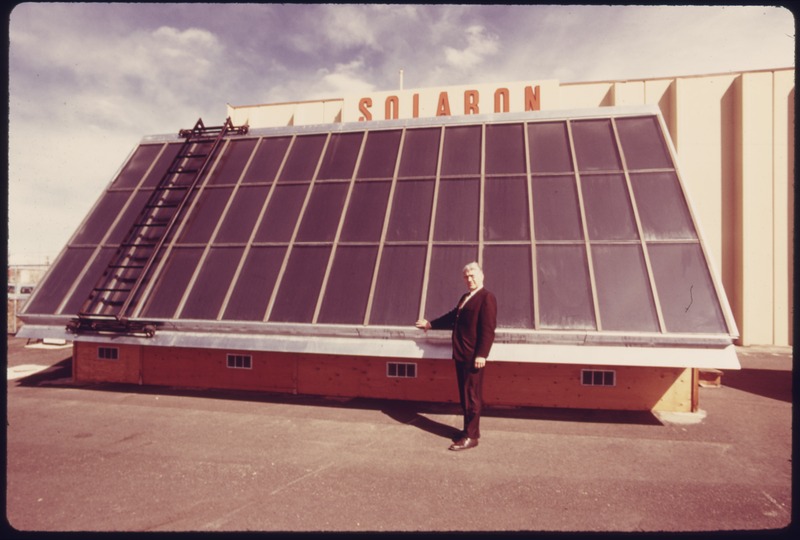

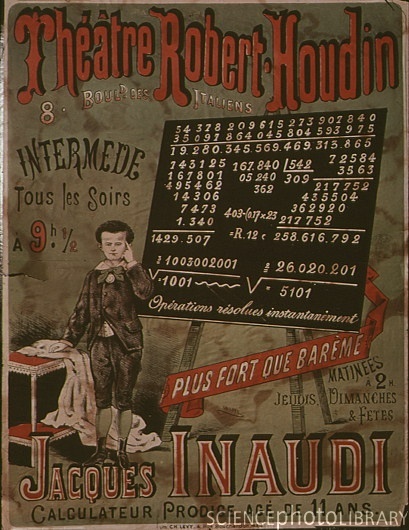

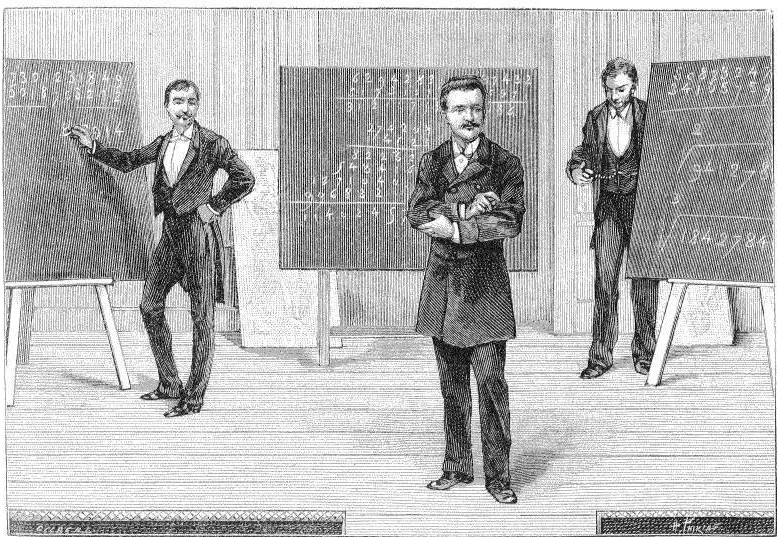

These fairs were equal parts technological debutante balls, theaters of wild futurist speculation, and pure circus entertainment. Cities vied to host them to signal their arrival into industrial modernity. Nations used them as public throwdowns. Corporations used them to spar over emerging markets. Artists, urban planners and architects used them to hawk entire imagined lifestyles.

It was through world fairs that a rapidly developing US announced its arrival on the global stage. From London in 1851, when it stole Britain’s thunder, to Chicago in 1893, when it formally claimed Great Power status, the young nation had taught the world about everything from bloody mechanised killing and newspaper circulation wars to electric lighting and manufacturing with interchangeable parts.

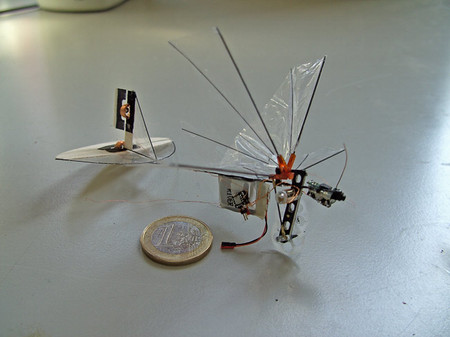

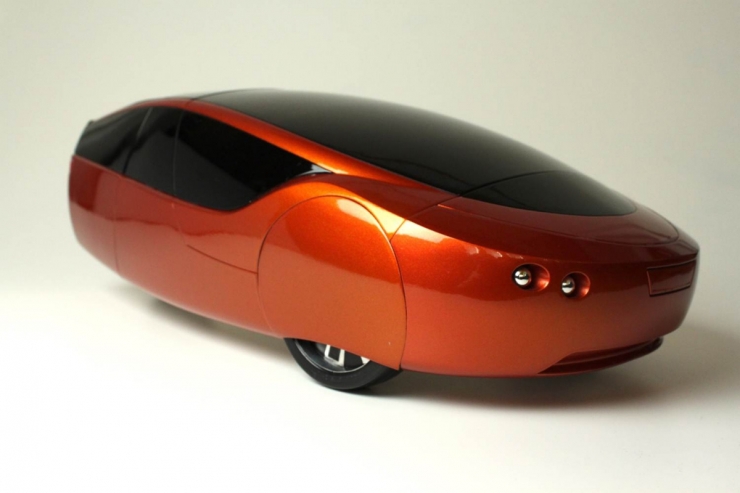

But beneath the pageantry and posturing, these fairs were more than technological Olympics. They spawned both the enduring mainstream folkways of modernity, such as suburban living and business-class air travel, as well as its dead-end subcultures, such as the world of flying-car loyalists. The fairs could do this because, fundamentally, they were large-scale exercises in what futurists call design fiction: indirect explorations of possible futures mediated by speculative, but tangible artifacts.“