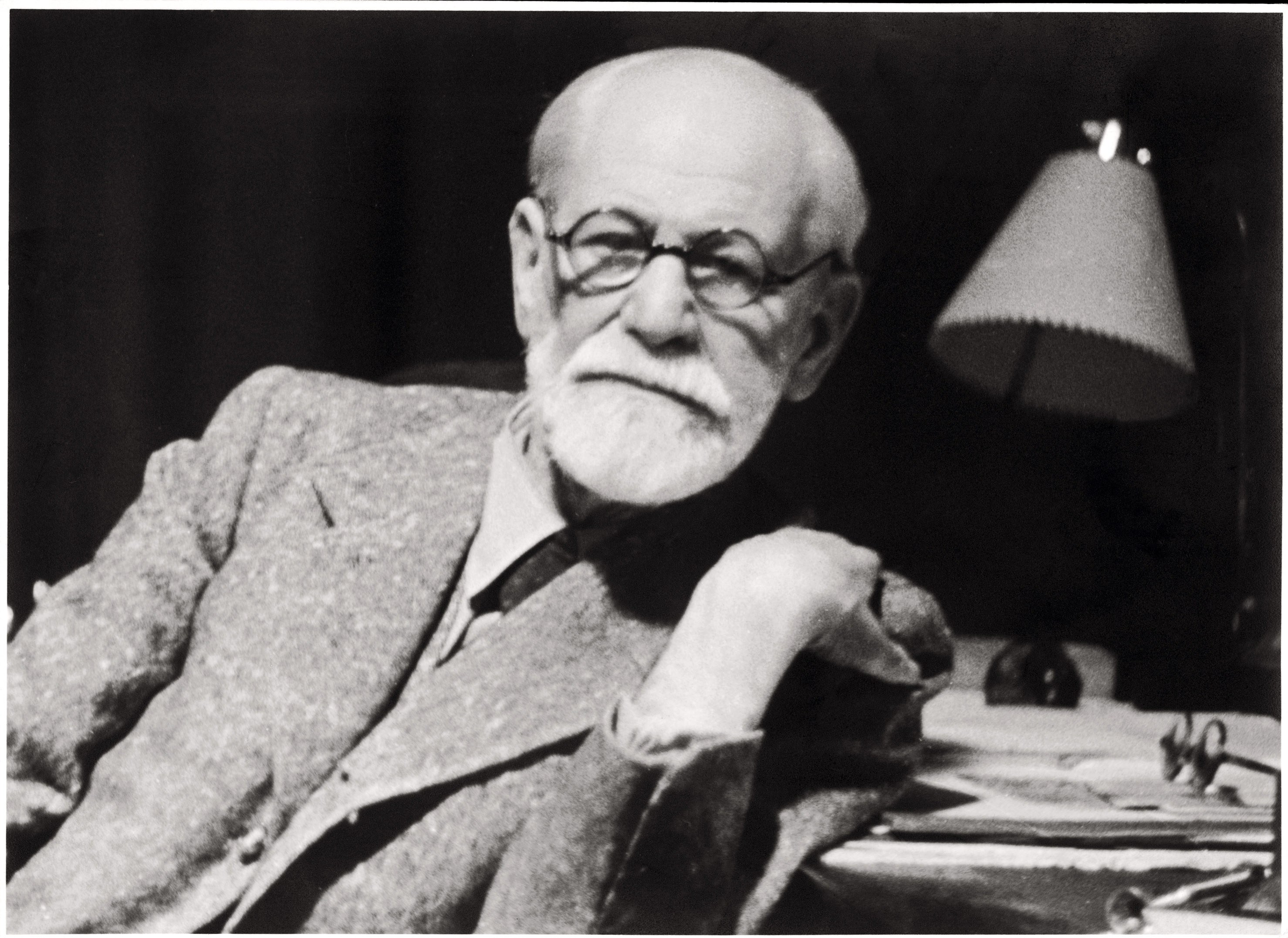

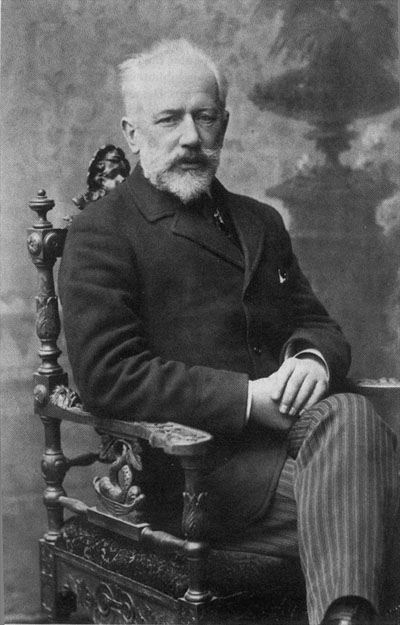

“Tchaikovsky contracted cholera by drinking unboiled water in a restaurant.”

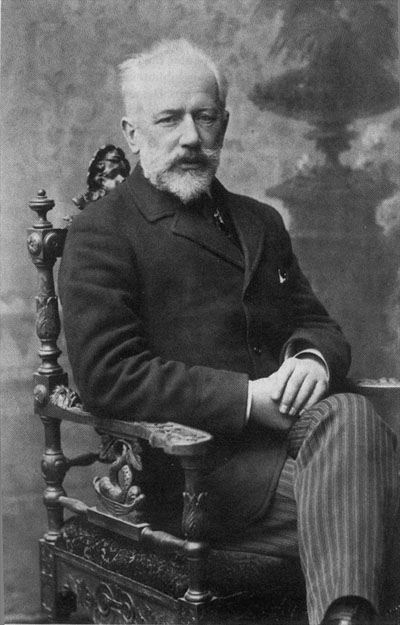

To put it crudely, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, one of humankind’s most refined composers, died because he drank water that had shit in it. We’re all a glass of shitwater, or something equally horrible, from death, even the best of us. Such is life: Luck plays a bigger role than we’d like to admit.

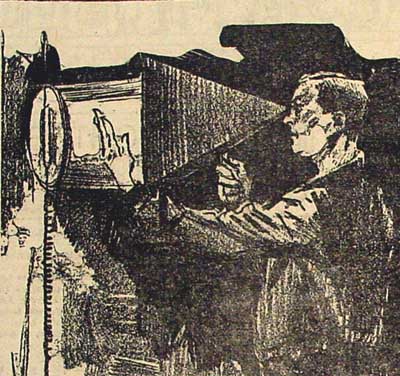

The announcement of Tchaikovsky’s death by cholera in the November 7, 1893 New York Times, which spells his name in a variety of ways, includes a passage about the Russian master’s visit to America. The opening:

“ST. PETERSBURG–Pierre Tschaikowsky, the Russian composer, died in this city last night. He died of cholera, hours after he fell ill.

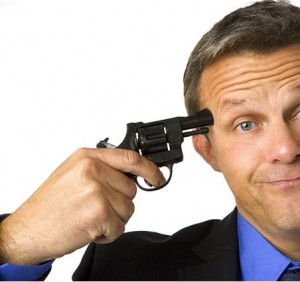

Tchaikovsky contracted cholera by drinking unboiled water in a restaurant.

________________

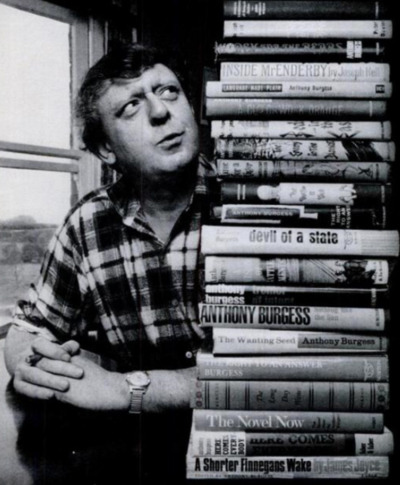

A cable dispatch from St. Petersburg brings the unexpected news that Peter Ilitsch Tschaikowsky is dead. This famous Russian musician was without much question the most strikingly original and forceful composer of the day, and his death at a time when his intellectual powers were, or ought to have been, at their maturity must be accounted a serious loss to music. The present is by no means richly productive in great orchestral works, and Tschaikowsky’s masterpieces have the hallmarks of real genius. If he had lived he would surely have given the world new works which it would have received with great gladness.

Tschaikowsky was the son of an engineer who held a post under the Government in the imperial mines of the Ural Mountain district. The musician was born at Wotkinsk, in the Province of Wlatka, on April 25, 1840. Like not a few other composers, the boy was not intended by his parents to follow in the footsteps of Glinka. He received his early education in the schools of his native place. In 1840, however, his father who was evidently a man of solid attainments, was appointed Director of the Technological Institute at St. Petersburg. In that city the son was entered as a student in the School of Jurisprudence, which is open only to the sons of Government officials of the higher orders. It was the father’s desire that the boy should enter the public service, and in 1859, when he had completed his course of study, he was appointed to a post in the Department of Justice.

In the meantime his love for music had declared itself, and while a law student he had made essays in composition. These attempts met with not a little opposition from his father, and for a time young Tschaikowsky’s musical studies were abandoned. But music eventually prevailed over law, and the consent of the father to his devotion to the study of composition was at length obtained. It was fortunate for Tschaikowsky that the great movement for the advancement of music in Russia had now begun. In 1862 Anton Rubinstein, the famous pianist and composer established his now celebrated Conservatory of Music at St. Petersburg. Tschaikowsky was one of the first of the institution’s many gifted pupils.

He devoted himself diligently to study until 1865. His principal masters were Zaremba, who taught him harmony and counterpoint, and Rubinstein, who taught him composition. In 1865 he was graduated with high honors, receiving a prize medal for his setting of Schiller’s ode, ‘An die Freude,’ of which he made a cantata. The composition.is not found among his published works.

In 1866 Nicolas Rubinstein, then the head of the conservatory, offered his the post of Professor of Harmony, Composition, and the History of Music. As his heart was in the Russian musical movement, he accepted the chair, and for twelve years did admirable work as an instructor. In 1878 he resigned his position in order to devote himself more assiduously to composition, in which he had already gained enviable distinction. He lived at various times in St. Petersburg, Italy, Switzerland, and Kiev. In recent years he had made his home at the last-named place, which is near Moscow.

Two years ago last May Tschaikowsky, at the invitation of Walter Damrosch, an enthusiastic follower and performer of his works, visited America, and appeared in the series of festival concerts with which the Music Hall, at Fifty-seventh Street and Seventh Avenue, was opened. The composer conducted his splendid third suite, his second piano concerto, in G, Opus 44, and two a capella choruses. The magnificent performance if the suite by the Symphony Orchestra under his electric leadership will long be remembered by music lovers, as will also also by Miss Aus Der Ohe’s playing of the piano concerto. The composer subsequently visited other cities, and was everywhere received with enthusiasm. …

Tschaikowsky was a prolific composer for a modern master, yet given to somewhat close self-criticism. Only three or four years ago he threw into the fire the score of his early ballet, ‘Wojowode,’ produced in 1860.”