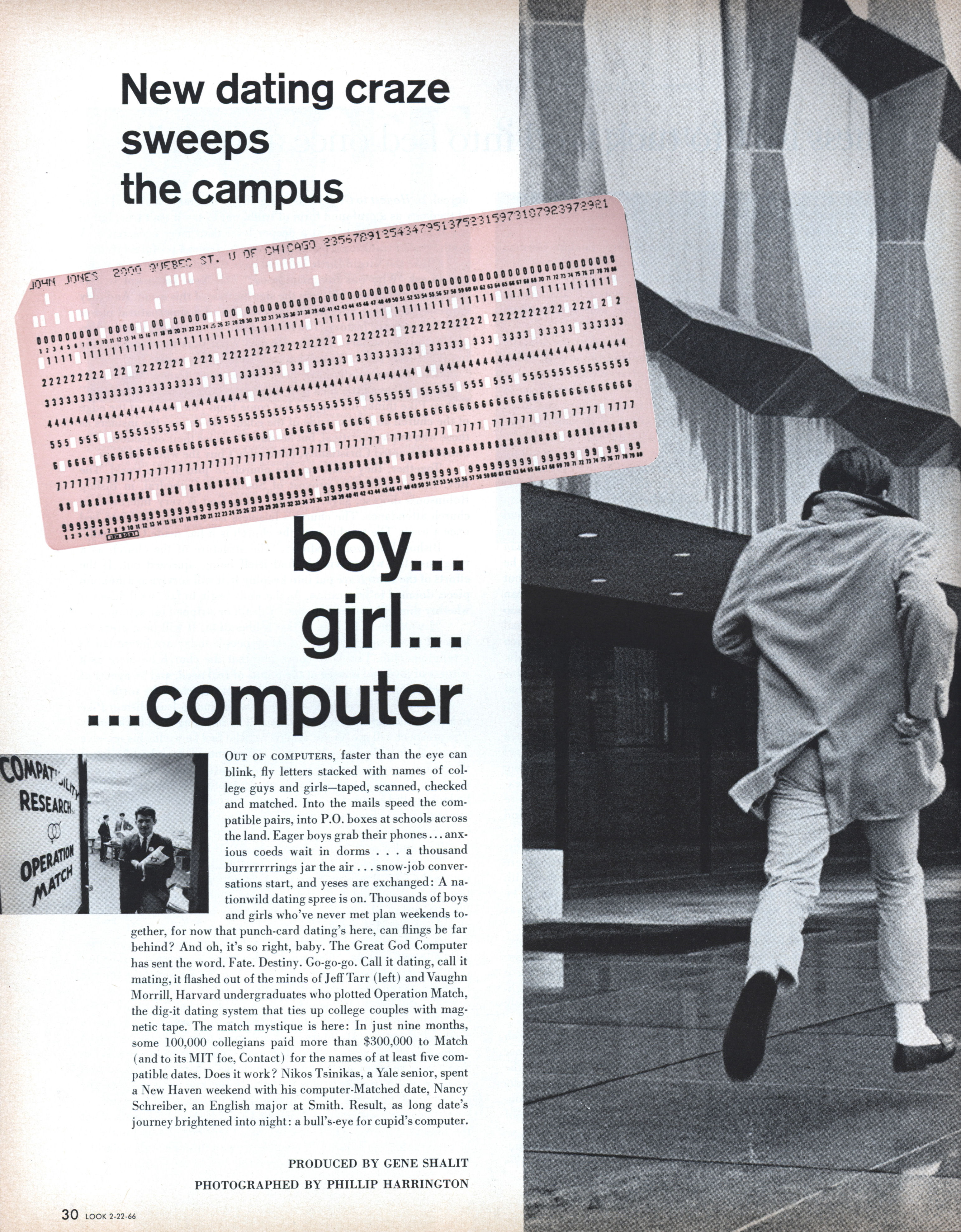

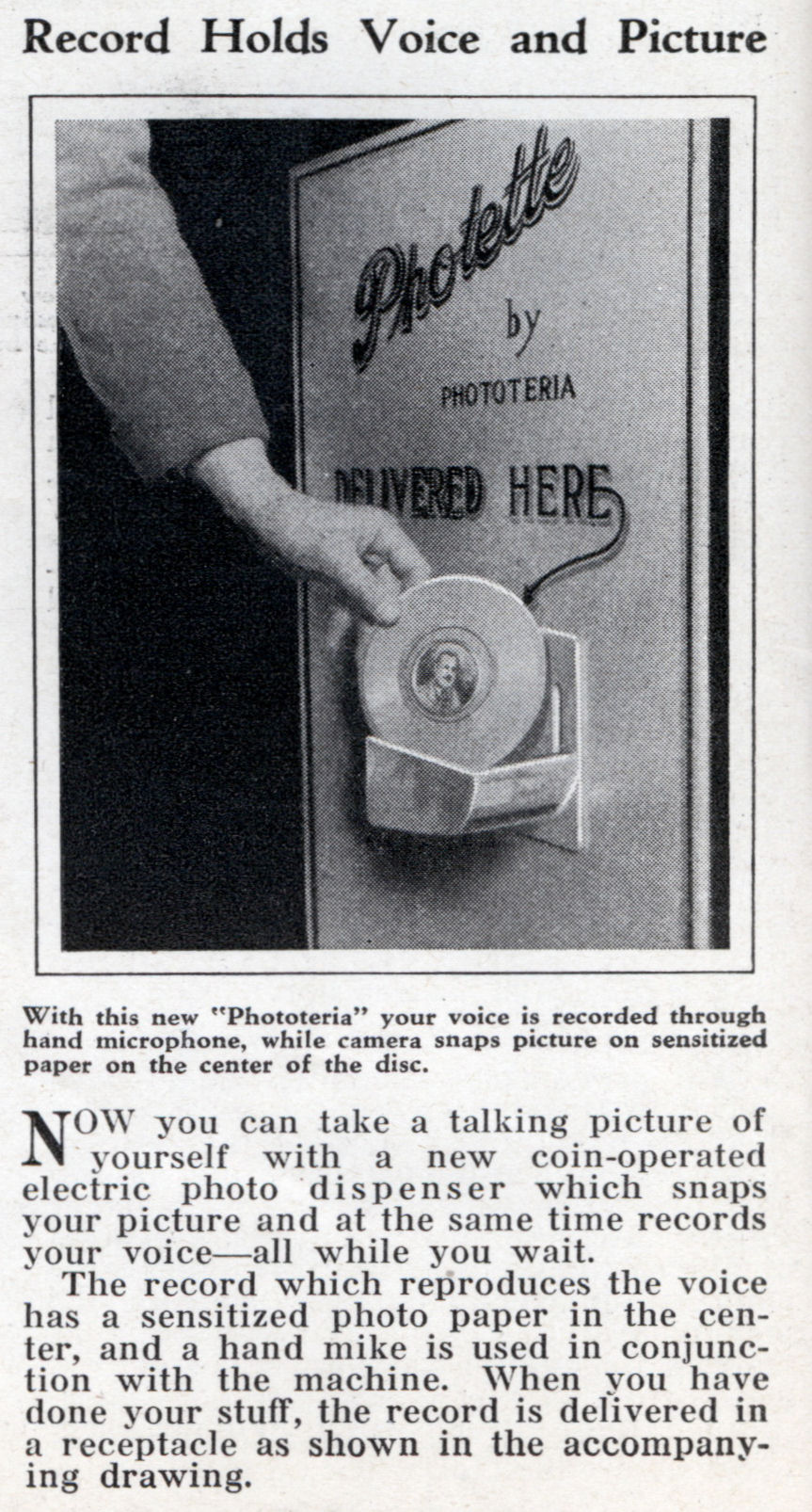

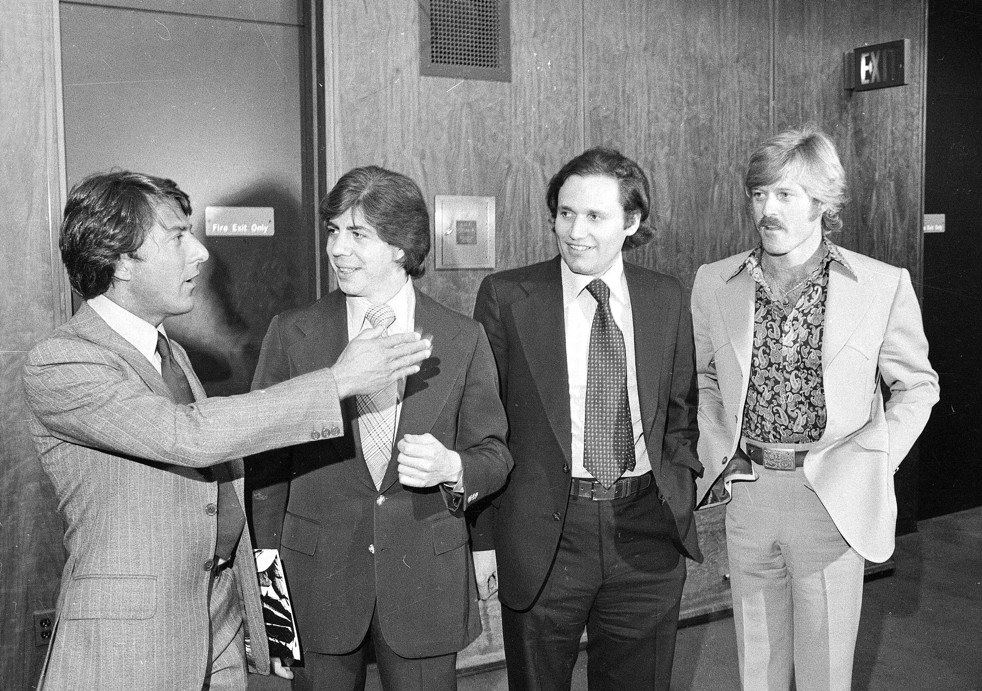

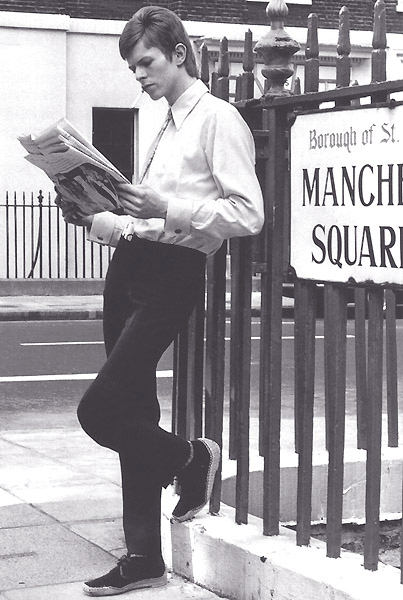

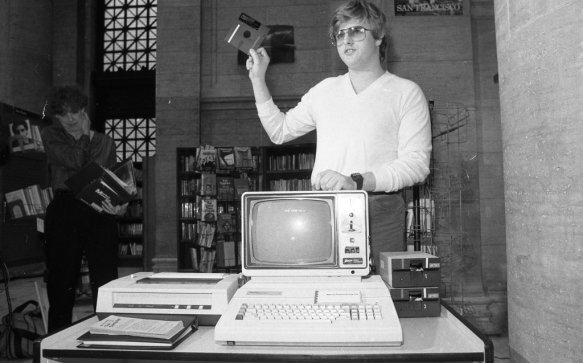

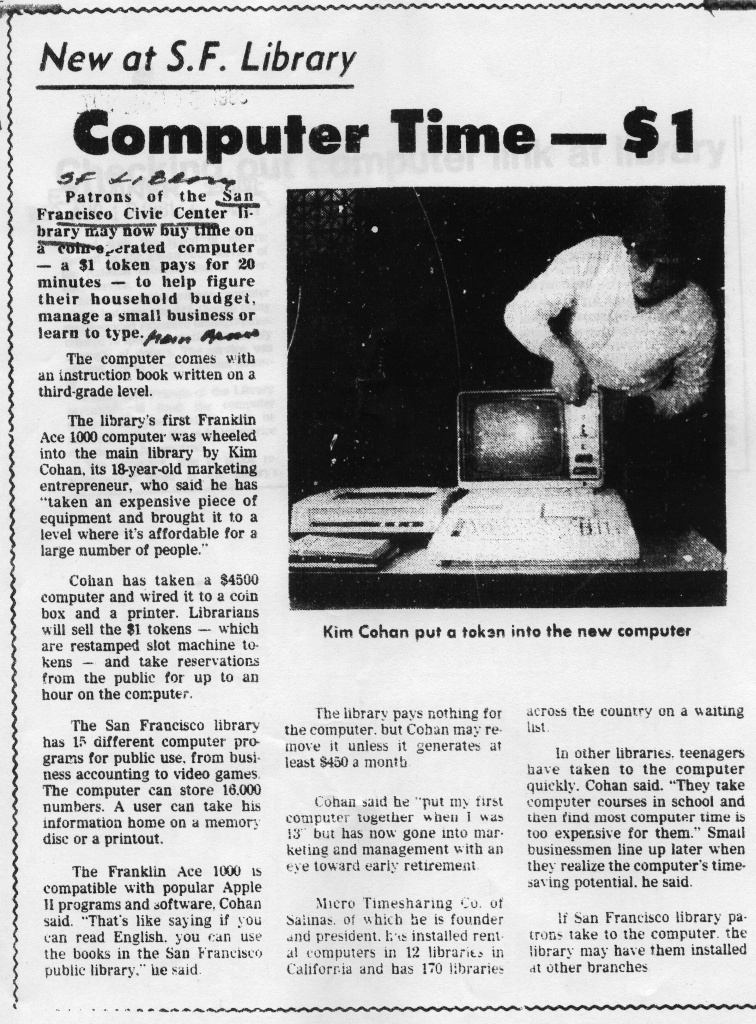

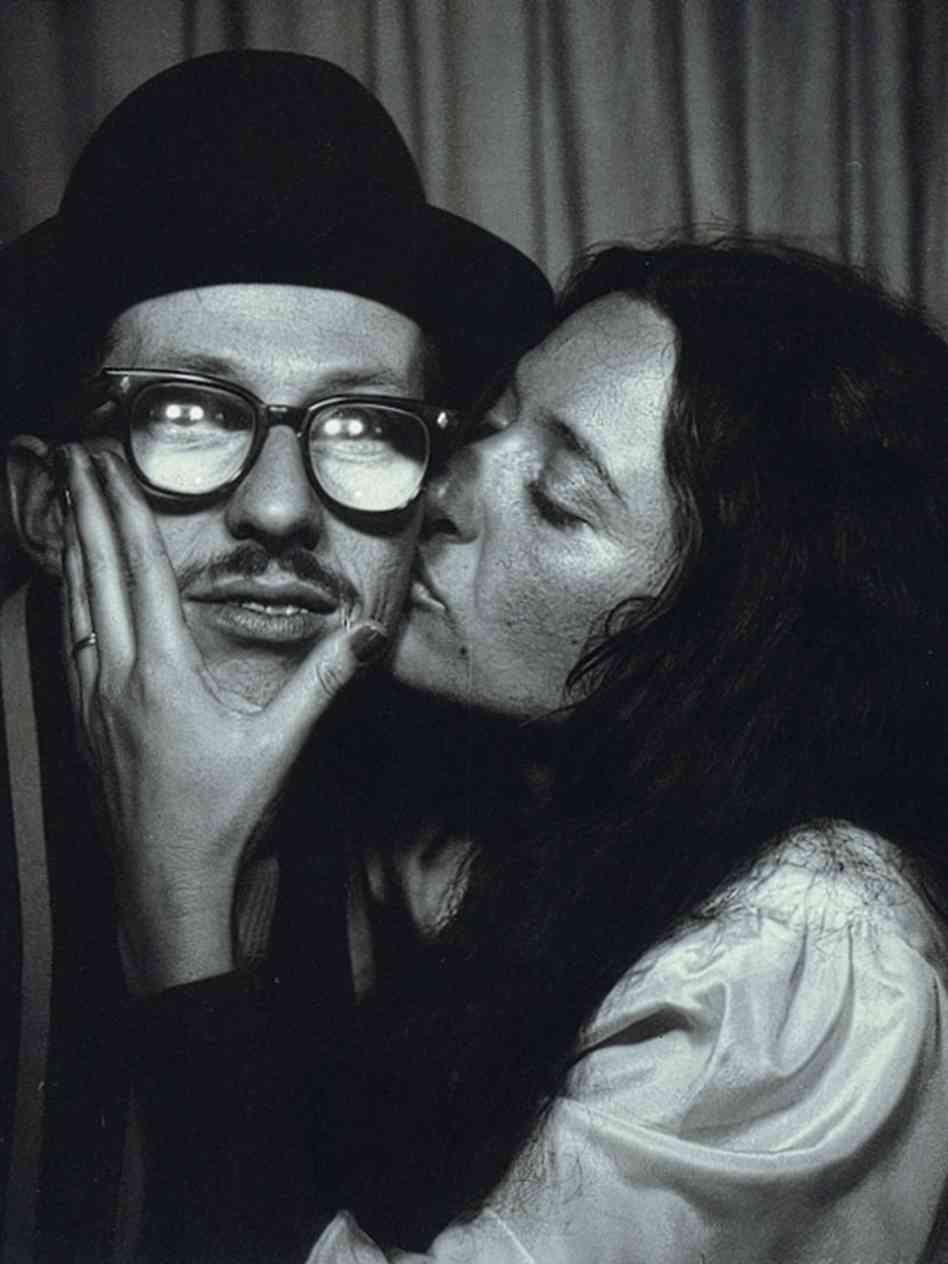

Out of computers, faster than the eye can blink, fly letters stacked with names of college guys and girls–taped, scanned, checked and matched. Into the mails speed the compatible pairs, into P.O. boxes at schools across the land. Eager boys grab their phones… anxious coeds wait in dorms … a thousand burrrrrrrings jar the air . . . snow-job conversations start, and yeses are exchanged: A nationwild dating spree is on. Thousands of boys and girls who’ve never met plan weekends together, for now that punch-card dating’s here, can flings be far behind? And oh, it’s so right, baby. The Great God Computer has sent the word. Fate. Destiny. Go-go-go. Call it dating, call it mating, it flashed out of the minds of Jeff Tarr (left) and Vaughn Morrill, Harvard undergraduates who plotted Operation Match, the dig-it dating system that ties up college couples with magnetic tape. The match mystique is here: In just nine months, some 100,000 collegians paid more than $300,000 to Match (and to its MIT foe, Contact) for the names of at least five compatible dates. Does it work? Nikos Tsinikas, a Yale senior, spent a New Haven weekend with his computer-Matched date, Nancy Schreiber, an English major at Smith. Result, as long date’s journey brightened into night: a bull’s-eye for cupid’s computer.

“How come you’re still single? Don’t you know any nice computers?”

Perhaps no mother has yet said that to her daughter, but don’t bet it won’t happen, because Big Matchmaker is watching you. From Boston to Berkeley, computer dates are sweeping the campus, replacing old-fashioned boy-meets-girl devices; punch bowls are out, punch cards are in.

The boys who put data in dating are Jeff Tarr and Vaughn Morrill, Harvard undergraduates. At school last winter, they and several other juniors–“long on ingenuity but short on ingenues”–devised a computer process to match boys with girls of similar characteristics. They formed a corporation (Morrill soon sold out to Tarr), called the scheme Operation Match, flooded nearby schools with personality questionnaires to be filled out, and waited for the response.

They didn’t wait long: 8,000 answer sheets piled in, each accompanied by the three-dollar fee. Of every 100 applicants, 52 were girls. Clearly, the lads weren’t the only lonely collegians in New England. As dates were made, much of the loneliness vanished, for many found that their dates were indeed compatible. Through a complex system of two-way matching, the computer does not pair a boy with his ‘ideal’ girl unless he is also the girl’s ‘ideal’ boy. Students were so enthusiastic about this cross-check that they not only answered the 135 questions (Examples: Is extensive sexual activity [in] preparation for marriage, part of “growing up?” Do you believe in a God who answers prayer?), they even added comments and special instructions. Yale: “Please do not fold, bend or spindle my date.” Vassar: “Where, O where is Superman?” Dartmouth: “No dogs please! Have mercy!” Harvard: “Have you any buxom blondes who like poetry?” Mount Holyoke: “None of those dancing bears from Amherst.” Williams: “This is the greatest excuse for calling up a strange girl that I’ve ever heard.” Sarah Lawrence: “Help!”

Elated, Tarr rented a middling-capacity computer for $100 an hour (“I couldn’t swing the million to buy it.”), fed in the coded punch cards (“When guys said we sent them some hot numbers, they meant it literally.”) and sped the names of computer-picked dates to students all over New England. By summer, Operation Match was attracting applications from coast to coast, the staff had grown to a dozen, and Tarr had tied up with Data Network, a Wall St. firm that provided working capital and technical assistance.

In just nine months, some 90,000 applications had been received, $270,000 grossed and the road to romance strewn with guys, girls and gaffes.

A Vassarite who was sent the names of other girls demanded $20 for defamation of character. A Radcliffe senior, getting into the spirit of things, telephoned a girl on her list and said cheerfully, “I hear you’re my ideal date.” At Stanford, a coed was matched with her roommate’s fiance. Girls get brothers. Couples going steady apply, just for reassurance. When a Pembroke College freshman was paired with her former boyfriend, she began seeing him again. “Maybe the computer knows something that I don’t know,” she said.

Not everyone gets what he expects. For some, there is an embarrassment of witches, but others find agreeable surprises. A Northwestern University junior reported: “The girl you sent me didn’t have much upstairs, but what a staircase!”

Match, now graduated to an IBM 7094, guarantees five names to each applicant, but occasionally, a response sets cupid aquiver. Amy Fiedler, 18, blue-eyed, blonde Vassar sophomore, got 112 names. There wasn’t time to date them all before the semester ended, so many called her at her home in New York. “We had the horrors here for a couple of weeks,” her mother says laughingly. “One boy applied under two different names, and he showed up at our house twice!”

Tarr acknowledges that there are goofs, but he remains carefree. “You can’t get hung up about every complaint,” says Tarr. “You’ve got to look at it existentially.”

Jeff, 5′ 7″, likes girls, dates often. “If there’s some chick I’m dying to go out with,” he says, “I can drop her a note in my capacity as president of Match and say, Dear Joan, You have been selected by a highly personal process called Random Sampling to be interviewed extensively by myself. . . . and Tarr breaks into ingratiating laughter.

“Some romanticists complain that we’re too commercial,” he says. “But we’re not trying to take the love out of love; we’re just trying to make it more efficient. We supply everything but the spark.”