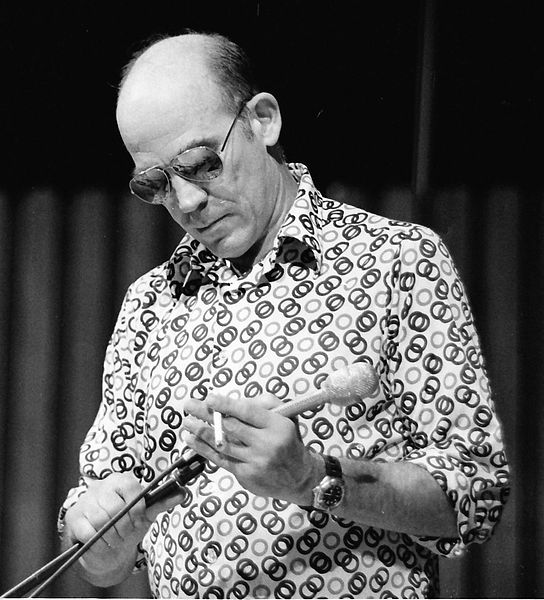

The Cold War gave genuine reason to be paranoid, though Bobby Fischer didn’t need any help. During his world-stopping chess series with champion Boris Spassky in 1972, the challenger showed up late, protested camera positions, etc. And his mental problems only increased with age. It’s a shame that two of the great American heroes of the 20th century–Fischer and Charles Lindbergh–ended up so damaged, so disgraced. They each had the world and let it spin from their grasp.

From coverage of the torturous, tremendous event in the July 24, 1972 Sports Illustrated: “Once after a visit to Caracas, Bobby Fischer remarked on how the dictator of Venezuela had chickened out. ‘He won’t go any place unless he has about six cars in front of him and six cars behind,” said the chess star, ‘because he’s afraid of being assassinated.’

‘Well, he nearly was,’ a companion explained. ‘His car was blown up and some people were killed.’

‘Yeah,’ said Fischer, ‘but he wasn’t in it. And ever since he’s been chicken. What kind of dictator is that?’

A similar question piqued watchers of Fischer himself last week—including the champion, Boris Spassky, who must have felt as though, like Alice, he had fallen down a rabbit’s hole. The American challenger for the world chess title had as usual been throwing his weight around dictatorially in Reykjavik, Iceland, site of his match with Spassky. But Fischer had also lost two straight games—the first one by an utterly out-of-character blunder and the second one by forfeit when he refused to leave his hotel room. What kind of chess genius was that?

A doomed one, suggested Icelandic Grandmaster Fridrik Olafsson right after Thursday’s forfeit. Fischer’s whole life is based on the assumption that he is the most compelling figure in chess. He had confidently predicted that this match would make his preeminence official. But his resistance to the playing conditions—he had demanded the removal of all movie cameras covering the match, saying they disturbed him even if he could not see or hear them—might well have cost him any chance at the title. If his intransigence should scuttle this $300,000 showdown, predicted Olafsson, “it would not be forgotten for a long time. And by then I’m afraid Bobby will be destroyed.” It conjured up thoughts of Paul Morphy, the 19th century American chess genius, who quit playing seriously at age 22 on obscure grounds of injured pride.

The comparison with Morphy underestimates Fischer’s redoubtable conception of himself. But hardly anyone in Iceland, the U.S. or the rest of the world seemed to care much if Fischer came to such an end last week. The press and public opinion, which had previously celebrated his eccentricities, were fed up.

The week before, Fischer had arrived in Iceland at the eleventh hour, his holdout of that moment having ended when an English millionaire sweetened the pot by $125,000, but now he seemed lost once more. John Lennon and Yoko Ono had recently sent him a chess set with white-on-white squares, all white pieces and this inscription: ‘For playing as long as you can remember where all your pieces are.’ But Fischer seemed to see nothing but black pieces. He feuded with his aides. He had committed the dictator’s cardinal sin—loss of control.

By Sunday Fischer had tickets on an afternoon plane to New York and the championships seemed doomed, but at the last moment a new accommodation brought him to, the chessboard once again.”