In 1975, Joe Garagiola hosted a remarkably stupid and wonderful bubble-gum blowing competition among baseball players, which was sponsored by Bazooka, a brand of gum favored by hoboes during World War II. One entrant was Philadelphia catcher Tim McCarver, whose head was the size of a medicine ball. The moment the contest ended, the players went in search of the nastiest groupies they could find.

You are currently browsing the archive for the Sports category.

Tags: Joe Garagiola, Tim McCarver

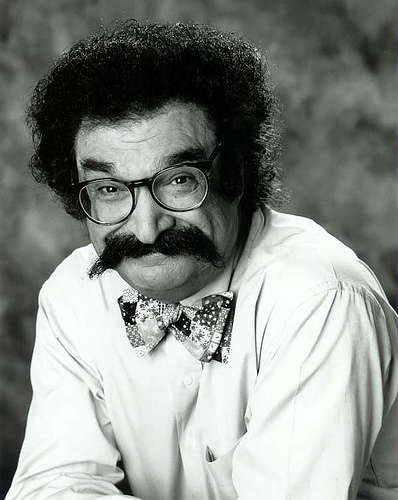

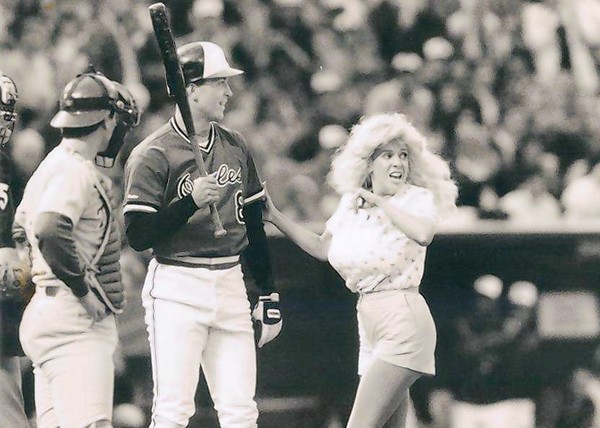

I recently posted a brief documentary about Morganna the Kissing Bandit. Here’s her 1976 appearance on To Tell the Truth. Fittingly, the host was a male sports figure, Joe Garagiola. On the panel was film critic Gene Shalit, who was mediocre but possessed a mustache.

When I used to see Shalit at movie screenings, he would sometimes be listening to a Walkman during the film and talking aloud to himself. One time when I was sitting a row ahead of him, he screamed at me when I got up to leave after the movie was over. “Get out of the way,” he hollered. “I’m trying to watch the credits.” The dipshit was sort of right.

Tags: Gene Shalit, Joe Garagiola, Morganna Roberts, Morganna the Kissing Bandit

There are many things wrong with Major League Baseball’s amateur draft–limits on signing bonuses, the inability to trade picks, etc. Perhaps most galling is that the largely politically conservative owners, who espouse the power of free markets, cling to their anti-trust exemption and curbs on competition in their sport because it suits their wallets. I have a fantasy that a large group of college kids who are top picks will band together and sue the game the way Curt Flood did on the major-league level in 1970. Of course, there are too many incentives keeping young players from doing such a thing.

The opening of Tim Marchman’s new Wall Street Journal piece, “Why Even Have Baseball’s Draft?“:

“All sports drafts are scams, more or less. No computer engineer right out of Carnegie Mellon has to go straight to a job at Comcast for a predetermined salary. Electronic Arts representatives aren’t lurking the halls of Northwestern with charts and craniometers. The concept is absurd on its face, and just as absurd when applied to young athletes.

What makes Major League Baseball’s draft, which takes place in two weeks, especially ridiculous is that in addition to being clearly unjust, it’s also inefficient. Drafting is no exact science in basketball or football, but at least in those sports the top amateur talents are both readily identified and actually available. Eight of the top 10 finishers in this year’s NBA Most Valuable Player voting were top-five draft picks overall, for example, and Marc Gasol and Tony Parker, who weren’t, were both special cases.

Of the 28 players who placed in the top 10 in last year’s baseball MVP voting or top five in Cy Young voting, though, a little more than half were first-round picks. Eight were originally signed as amateur free agents, meaning they weren’t subject to the draft at all. The draft isn’t a lottery, but it’s closer than it should be given that its nominal purpose is to distribute the best talent to the worst teams.

One sign of this randomness is the way expected returns flatten out through the draft. This year, the Mets, who were lousy last year, have the 11th overall pick, while the Yankees, who were very good, have the 26th. If the draft worked as it’s supposed to, you’d expect that the Mets’ pick would be substantially more valuable, based on historical data.

That isn’t even close to being true, though.”

Tags: Tim Marchman

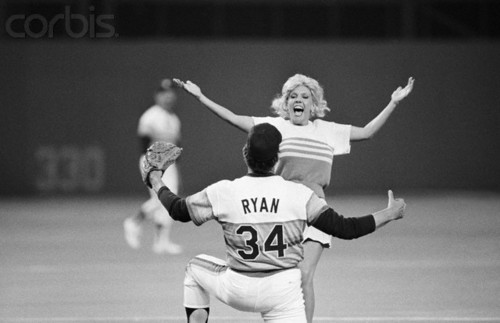

Morganna Roberts was a bosomy 13-year-old girl in 1960 when she first stepped onto a stage at a strip club, in an era when America was tormented by desire and morality, wanting all manner of urges satisfied and needing to punish the one who provided the satisfaction. Not content to just be ogled and cursed as the star of the burlesque circuit, the teen dreamed of a bigger spotlight–and found it. In the years before women were encouraged to take the field and participate in pro sports, she and her Dolly Parton-ish figure stormed the gates. Morganna, dubbed “the Kissing Bandit,” gained notoriety beginning in 1969 for running onto the playing field at pro games and attempting to plant one on the biggest male athletes of the day, from Pete Rose to Fred Lynn to Nolan Ryan. She was a groupie who only kissed, a streaker even when she kept her clothes on, and someone who was not very popular with women in a time when Billie Jean King was battling the sexist pigs on the court. Only in retrospect can she be appreciated as a feminist icon.

A short film by Adam Kurland about Morganna’s life as a public jiggler, “Always Leave Them Wanting More,” can be viewed here. (Thanks Hairpin.)

Tags: Adam Kurland, Morganna Roberts, Morganna the Kissing Bandit

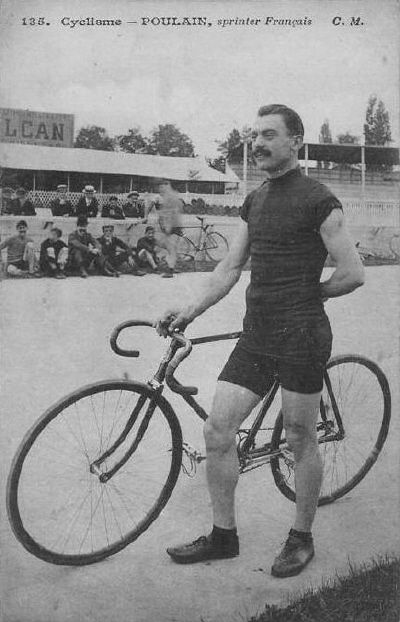

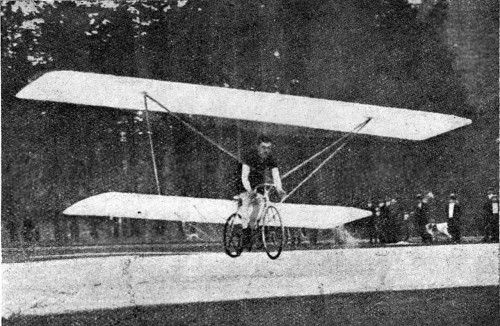

A small plane powered for a matter of feet by a person on a bicycle is utterly useless in a practical sense, yet achingly beautiful to admire, perhaps because of the near-futility of the effort. From a July 10, 1921 New York Times article about French wheelman Gabriel Poulain, who was a pioneer in this odd endeavor:

“Paris–Gabriel Poulain, the French champion cyclist, succeeded this morning in the Bois de Boulogne in winning the Peugot prize of 10,000 francs for the flight of more than ten meters distance and one meter high in a man-driven airplane. In an ‘aviette,’ which is a bicycle with two wing planes, he four times flew the prescribed distance, his longest flight being more than twelve meters, or about the same number of yards.

Poulain for several years has been devoting himself to the solution of the problem of flight by the power of his own muscles and several times has come near winning a prize. This morning’s exhibition, however, was by far the most successful, a cyclist never before having been able to rise from the ground a sufficient height to enable him to cover more than six or seven meters.

For today’s attempt Poulain altered the angle of the small rear plane of his machine and it was this alteration, it seems, that solved the problem.

Poulain made his attempt just after dawn on the smooth road at the entrance to the Longchamps race course. Several members of the Aero Club, donors of the prize and a large company of journalists and photographers were present. A square twenty meters each away was carefully measured off and chalked so as to mark the points at which the ‘aviette’ must rise one meter from the ground and that two flights must be made in opposite directions.

Rides Smoothly in Air

Poulain, who was confident that this time he was going to succeed, rode his machine at top speed toward the chalked square. As he entered it he released the clutch which throws the wing into proper position and at once the miniature biplane rose from the ground gracefully and steadily to a height of more than a meter.

The flight was as steady as that of a motor-driven airplane and Poulain declared afterward that the motion was smoother than when traveling along the ground. When the judges measured the distance between the wheel marks on the chalk they found it lacked only two centimeters of being twelve meters.

Poulain’s flight in the opposite direction was not quite so successful, though he succeeded in covering eleven and a half meters. In landing he broke two spokes of the rear wheel.

M. Robert Peugeot declared the prize won, but Poulain wished to make further proof of the powers of his machine. After changing the wheel he started from positions chosen by the judges, and in each case he succeeded in covering the prize-winning distance. His longest flight was the last, of twelve meters thirty-two centimeters.

In order to cover so great a distance Poulain worked up to a speed of forty-five kilometers an hour on the ground. According to his own estimate, the muscular force required for flight is equal to three horse power. The total weight of the machine, with the wings, is seventeen kilogrammes, or about thirty-seven pounds, and the cyclist himself weighs seventy-four kilograms, or about 165 pounds.

After the flight Poulain declared that he intended to set at work at once on another plane, which, he believes, will enable him to fly 200 to 300 meters. On this machine he will make use of a propeller instead of depending, as he did today, simply on impetus.

Once in the air, Poulain says that not so much power is needed as for the take-off. He says the pedal-worked propeller will be strong enough to continue flight for a considerable distance without fatigue.”

Tags: Gabriel Poulain

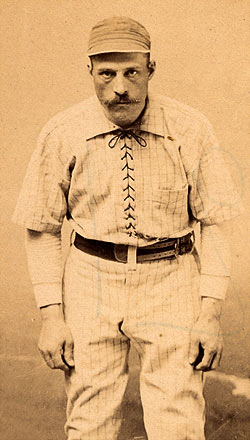

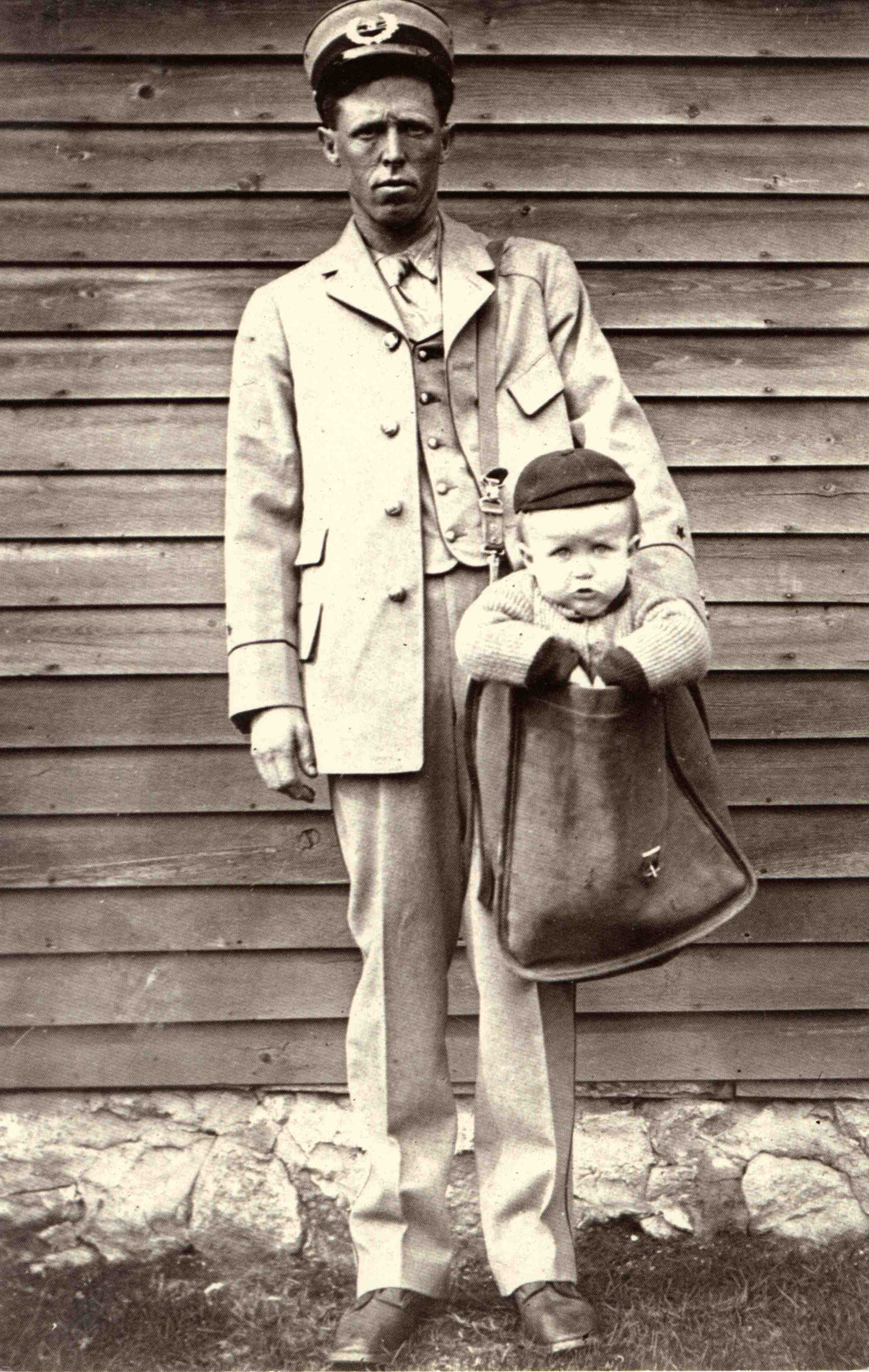

Though his child has long vanished from the sporting scene, Edward Payson Weston was known during his lifetime as the “Father of Modern Pedestrianism,” a pastime that rewarded those who could hoof great distances with surprising speed. I’ve blogged about the world-class walker before, when Brian Phillips of Grantland wrote a sparkling piece about the recent Weston biography, A Man in a Hurry. In this classic photograph, the legendary athlete, profiled at 70 years old, was far removed from his glory days of the 1860s-70s, but perhaps because of good health brought about from his peripatetic exploits, he was still twenty years from his death. Of course, it must be noted that his demise may have been hastened by an accident in 1927 in which he was struck by a NYC taxi, as the roads, which had become the domain of cars, had little room for a remnant of the 1800s who was so accursed by their encroachment. Weston could see the future and didn’t like it, though he was helpless, as we all are, to stop it.

In the same year that this image was taken, the native Rhode Islander wrote an article about one of his cross-country walks, a planned 100-day excursion from New York to San Francisco, for the July 16, 1909 New York Times. The article:

“San Francisco, Cal.–Having completed my walk from New York City to San Francisco last night, and enjoyed a restful sleep. I walked to the Post Office Building here this morning and delivered to Postmaster Fiske of San Francisco a letter which I carried in my walk from Postmaster Morgan of New York City. I received a cordial greeting from Postmaster Fisk and his subordinates.

A pleasant incident of my arrival at Oakland last night was the hearty welcome and congratulations extended to me by officials and employees of the Southern Pacific Railroad Company. This company did so much for me that I fail to find words to express my appreciation.

Regarding my feelings and condition, I would say that I feel like uttering bitter words, but do not feel inclined to make excuses.

I have received hundreds of letters and telegrams congratulating me on my wonderful achievement, and each one makes me wish I deserved it. Full of vigor and strength, I am disappointed that the elements were against me, and I frankly acknowledge that had it not been for the unbounded kindness of the officers and employees of the Southern Pacific Railroad Company, I should not have dared to come further than Ogden, Utah. I practically had the right of way on the railroad, and every engineer tooted the whistle on his engine as it passed me.

I contend I walked a distance of upward of 4,000 miles in 104 days and 5 hours, and while it exceeds the distance between New York and San Francisco nearly 700 miles, and far excels any previous record, yet technically it is a failure, and I do not feel inclined to close my public career with a failure.

The expenses of this walk were upwards of $2,500. Some dozen prominent cities in the East have made offers to arrange for testimonial lectures on my return, not only to help liquidate my financial loss, but to show that my object lesson in the journey, in striving to elevate in popular esteem the exercise of walking, is appreciated.

If in the next two weeks I shall receive assurances from a sufficient number of cities and towns between Omaha and New York that they will arrange for lectures and send such word to me in care of the Southern Pacific Railroad Company, San Francisco, then I will try to prove myself worthy of their confidence and esteem by showing how easy it is for any one to walk from San Francisco to New York by direct route within 100 secular days.

There are three very dear friends who oppose this extra walk, but when I convince them that it is my only salvation, and that it would still keep me young and healthy, I know they will fall in with my plans.

Meanwhile the only trouble I have is an awful appetite.”

Tags: Edward Payson Weston

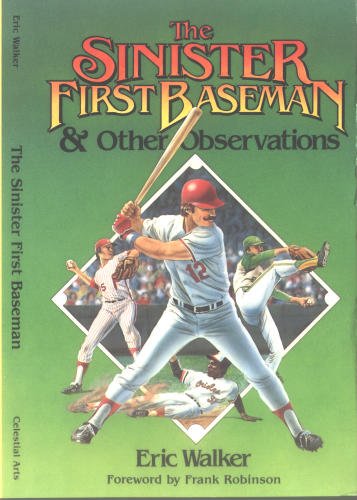

At present, there are 13 used copies of Eric Walker’s oddly titled, out-of-print 1982 baseball-themed paperback, The Sinister First Baseman & Other Observations, on sale from Amazon sellers, and the cheapest one, in merely “Acceptable” condition, goes for $104.96. Who, exactly, is Eric Walker and why does he have so much value for so few people?

There were always those who suspected that baseball’s conventional wisdom was not so wise, but in the 1970s, Walker, a Bay Area baseball fan birthed the idea of Moneyball before Sandy Alderson or Billy Beane had entered the game. Even he, however, had an important precursor. From “The Forgotten Man of Moneyball,” Walker’s 2009 Deadspin article, a passage about his inspiration:

But who am I, and why would I be considered some sort of expert on moneyball? Perhaps you recognized my name; more likely, though, you didn’t. Though it is hard to say this without an appearance of personal petulance, I find it sad that the popular history of what can only be called a revolution in the game leaves out quite a few of the people, the outsiders, who actually drove that revolution.

Anyway, the short-form answer to the question is that I am the fellow who first taught Billy Beane the principles that Lewis later dubbed ‘moneyball.’ For the long-form answer, we ripple-dissolve back in time to San Francisco in 1975, where the news media are reporting, often and at length, on the supposed near-certainty that the Giants will be sold and moved. There sit I, a man no longer young but not yet middle-aged, a man who has not been to a baseball game — or followed the sport — for probably over two decades, but a man who in childhood used to paste New York Giants box scores into a scrapbook, and who remembers, dimly but fondly, such folk as Whitey Lockman and Wes Westrum.

Carpe diem, I think.

With my lady, also a baseball fan of old, I go to a game. We have a great time; we go to more games, have more great times. I am becoming enthused. But I am considering and wondering — wondering about the mechanisms of run scoring, things like the relative value of average versus power. Originally an engineer by trade, I am right there with Lord Kelvin: ‘When you cannot measure it and express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a very meagre and unsatisfactory kind.’ I fiddle with some numbers; but I vaguely remember Branch Rickey’s work, the cover story in Life magazine for Aug. 2, 1950, [ed. note: it was actually 1954 and not a cover story] and think that I may not need to reinvent the wheel. I go to the San Francisco main library, looking for books that in some way actually analyze baseball. I find one. One. But what a one.

If this were instead Reader’s Digest, my opening of that book would be ‘The Moment That Changed My Life!’ The book was Percentage Baseball, by one Earnshaw Cook, a Johns Hopkins professor who had consulted on the development of the atomic bomb. Today, when numerical analysis of baseball performance is a commonplace, it is hard to grasp how revolutionary, even shocking, were the concepts Cook was developing (Rickey’s work, which had quickly dropped off everyone’s radar, notwithstanding). The book was, and remains, awe-inspiring.•

Tags: Billy Beane, Earnshaw Cook, Eric Walker, Sandy Alderson

Baseball pitchers should have been wearing padded caps or fitted helmets for years, but, you know, Bud Selig is MLB Commissioner, so everything has to move at a glacial pace. The only good thing to come out of the harrowing recent incident that saw Toronto pitcher J.A. Happ suffer a skull fracture after being struck by a batted ball was the solution to the problem brainstormed by Tampa Bay’s southpaw Matt Moore. From Roger Mooney in the Tampa Tribune:

“ST. PETERSBURG – It was after the shock of seeing the line drive slam into the side of J.A. Happ’s head had subsided a bit – after word spread through the Rays dugout that as scary as it seemed, the Toronto starter would be OK – when the Tampa Bay pitchers discussed ways to avoid such incidents.

Matt Moore suggested a sensor inside the baseball and one inside the pitcher’s cap that would cause the ball to explode when it came within a certain distance of the pitcher’s head.

‘That’s Matt’s great idea. I kind of like it,’ Rays pitcher David Price said.”

Tags: Bud Selig, David Price, J.A. Happ, Matt Moore, Roger Mooney

I was taken aback–and perhaps you were?–when I heard that Bennett Miller had cast Steve Carrell as John du Pont in Foxcatcher, the forthcoming film about the wealthy benefactor of amateur wrestling, a schizophrenic whose money kept treatment at a distance, who descended into utter madness in the 1990s, and ultimately murdered Olympic hero David Schultz. The heavily armed du Pont, who’d played host to underdog sports since the 1960s, was arrested only after a two-day stand-off with the police. The opening of “A Man Possessed,” Bill Hewitt’s 1996 People article about the tragedy:

“Lately he had started telling people that he was the Dalai Lama. If anyone refused to address him as such, he simply refused to talk to them. That was bizarre, but then John E. du Pont, 57, a multimillionaire scion of the fabled industrial family, had always been odd. For fun he drove an armored personnel carrier around his 800-acre estate, Foxcatcher. He complained about bugs under his skin and about ghosts in the walls of the house. By and large, friends and family shook their heads, fretted about his ravings—and waited for the inevitable breakdown. ‘John is mentally ill and has been mentally ill for some time,’ says sister-in-law Martha du Pont, who is married to John’s older brother Henry. ‘But this year he really went over the edge.’

No one realized how far over until Friday afternoon, Jan. 26. Around 3 p.m., Dave Schultz, 36, a gold medalist in freestyle wrestling at the 1984 Olympics, was out working on his car at Foxcatcher, in leafy Newtown Square, Pa., 15 miles west of Philadelphia, where du Pont had established a residential training facility for top-level athletes. Suddenly du Pont pulled into the driveway of the house where Schultz lived with his wife, Nancy, 36, and their two children, Alexander, 9, and Danielle, 6. From the living room, Nancy heard a shot. When she reached the front door she heard a second. Looking out in horror, she saw a screaming du Pont, sitting in his car, extend his arm from the driver’s side window, take aim at her husband, facedown on the ground, and pump one more bullet into his body. After pointing the gun at Nancy, du Pont drove down the road to his home, leaving her to cradle her dying husband.

During the two-day standoff that ensued, some 75 police and SWAT team members surrounded the sprawling Greek-revival mansion that du Pont called home. Finally, on Sunday afternoon, du Pont emerged, unarmed, to check on the house’s heating unit, which the police had turned off, and was taken without a shot being fired. That evening, a gaunt, ashen-faced du Pont was arraigned in a Newtown Township courtroom on a charge of first-degree murder, which in Pennsylvania can carry the death penalty. As investigators tried to piece together a motive for the seemingly senseless killing, there emerged the sad, scary portrait of a man believed to be worth more than $50 million who was rich enough to indulge his madness and to put enough distance between himself and the world at large to ensure that no one really bothered him about it.”

Tags: Bennett Miller, Bill Hewitt, David Schultz, John du Pont, Steve Carrell

In wake of the NBA’s Jason Collins announcing that he’s gay–and the largely positive and supportive response to him–Deadspin unearthed a 1982 Inside Sports article about Glenn Burke, a gay pro athlete during the 1970s, who was out to his teammates in a less-enlightened era for sexual politics. The opening:

“The game is over and the baseball player sits in the hotel lobby, his eyes fixed on nothing. He thinks his secret is safe but he is never quite sure, so at midnight in the lobby it is always best to avoid the other eyes. He neither hears the jokes nor notices that a few teammates are starting to wear towels around their waists in the locker room. He does not want to hear or see or know, and neither do they.

The baseball player waits until the lobby empties of teammates and coaches. Some are in the bar, some out on the town, some in their rooms. Some, of course, have found women. He walks briskly out the door toward the taxicab, never turning his head to look back. He mutters an address to the driver and has one foot in the cab. …

‘Hey, where you going, man? You said you were staying in tonight.’

The baseball player feels his lie running up the back of his neck. ‘Changed my mind.’

‘Can I come with you? I got nothing going tonight.’

The baseball player pauses. ‘You don’t want to go where I’m going,’ he says at last. He is leaving a crack there, in case this teammate knows the secret and really would like to go with him.

‘Okay—have it your way.’

The baseball player is in the back seat, the door slams, his heart slams, the cab is pulling away. Fifteen minutes later it stops a block from the place the passenger actually intends to go. He pays the driver. Did the driver look at him sort of funny?

The baseball player steps out and walks back a block, his face turned 90 degrees to his left shoulder, away from the traffic, just in case. What if he meets someone he knows there tonight? There was the ballplayer’s brother the one night and the son of.a major league manager another. Man, they have to know, don’t they? And if he is recognized tonight, should he pretend he is someone else?

Suddenly he is pulling open the door and the men inside smile and the music swallows him and for a few hours in the bar the baseball player does not feel so alone.”

Tags: Glenn Burke\, Jason Collins

For people with systemic issues, there’s little hope apart from the short-term. Give a lot of money to someone who spends compulsively and is in debt and pretty soon they’ll have spent compulsively and been returned to indebtedness. But if you’re free from these issues, a little luck–or a lot of it–can make you into the thing you know you are in your head, because the only resources you lack are external. From Joe Drape’s New York Times article about Conor Murphy, a racehorse stablehand with a hunch–five hunches, actually:

“GOSHEN, Ky. — Last spring, Conor Murphy was a hired hand who spent his days galloping racehorses, combing knotted manes and shoveling manure in a stable in Berkshire, England.

Mr. Murphy, 29, knew his horses well. He was able to tell which ones were on their toes and which ones needed a little more care. He also knew his way around a betting window. On a hunch, he bet $75 on five of his favorites. It was the sort of desperate stab that only a man who loves horses would make.

But he won — big. His $75 bet paid more than $1.5 million, enough to put down the shovel and become his own boss.

Now he lives in Kentucky, training horses for some of the most prominent figures in racing. On Saturday, he will be at the Kentucky Derby, rooting for Lines of Battle, a horse owned by one of his clients.

“Pure luck,” Mr. Murphy said of his life-changing wager. His past year reads like something out of a movie script, and his big bet has become the stuff of lore for gamblers from the backsides of American racetracks to the training yards of England and Ireland.”

Tags: Conor Murphy, Joe Drape

Because the word’s highest cancer rates aren’t killing citizens at a fast-enough pace, China may be in the midst of importing American football. NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell has at least 99 problems–many of them-concussion-related–but he gets breathless over the thought of cracking the world’s biggest market. The opening of “Hard Knocks: Shanghai,” Hua Hsu’s new Grantland article:

“The National Football League currently maintains four offices around the world. There is an office in Mexico City. The NFL has been popular in Mexico since at least the 1970s, and some of the largest-ever crowds to watch preseason and regular-season games were recorded in the nation’s capital, where the league has staged games since 1994. There’s another office in Toronto, where the league claims a fan base of nearly 1 million, the most die-hard among them along the border. NFL Europa shut down operations in 2007 but an office continues to thrive in London, where an annual regular-season game is played at Wembley Stadium. Commissioner Roger Goodell has even mused, carefully and obliquely, about one day placing a franchise there.

The last office is in Shanghai.

How does one begin to explain how unlikely NFL China is? Anything you want to assume about a nation that constitutes nearly 20 percent of the world’s population is probably true. China is whatever you want it to be: Massive and diverse and black-hair sameness, ancient and postmodern and blink-of-an-eye changing, it requires a different scale of description. But it’s probably not the riskiest generalization to suggest that China does not conform to anyone’s vision of a hotbed for American football. When I arrived in Shanghai, I was offered a litany of reasons, ranging from the cultural to the genetic, for why the sport would never catch on among locals. For example: There isn’t a deeply ingrained sports culture in China, and what little energies were devoted to following such things usually involved international competition. Team sports aren’t big in China, either, and the one-child policy has made parents more averse than ever to subjecting their kids to potential harm. And beyond all this, there’s football itself, which has never been an intuitive product for American export. Even nations with an appetite for American things have traditionally found football exotic and inscrutable, one of those aspects of the culture that simply doesn’t translate well.

But something unusual is happening throughout China’s major cities, where football is one of the fastest-growing sports. ocal Chinese kids are buying cleats and pads and starting teams and football clubs.”

Tags: Hua Hsu, Roger Goodell

Tags: Muhammad Ali, Nikki Giovanni

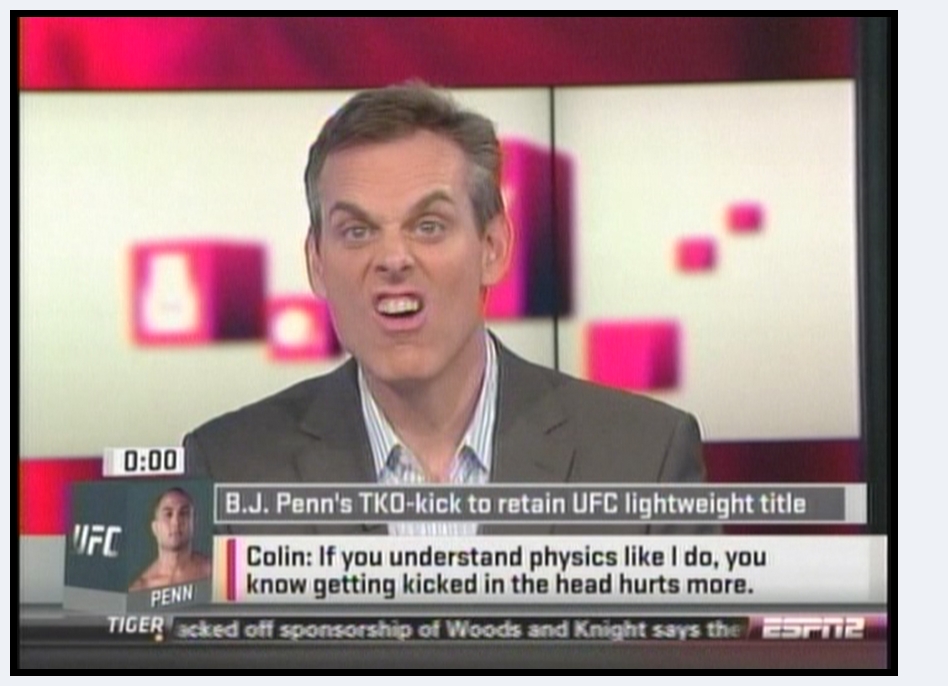

ESPN’s Colin Cowherd is a hideous man, full of bluster, arrogance and wrongheadedness–and it’s obvious that he’s a sign of the times in American broadcasting. He creates elaborate, asinine theories and stuffs them full of “facts” that are usually not true. His predictions are almost always wrong. If Cowherd tells you to bet the rent money on something, you best sock it under a mattress. But being wrong and obnoxious has yet to cost him because like most pundits, he’s not in the business of being right. He’s in the business of being loud and of being a brand.

Just one small example: Before the 2012 baseball season, the Texas Rangers let pitcher C.J. Wilson become a free agent, instead opting to invest money in Japanese pitcher Yu Darvish, whom the organization had scouted heavily. Cowherd went on the radio with one of his typical idiotic rants, stating authoritatively that this was an example of how people are attracted to the unknown instead of appreciating what has worked for them, that the team had fallen in love with an ideal instead of understanding what they already had was better, that Wilson would prove to be the superior pitcher. Mark my words, Cowherd said.

He didn’t take into account that Darvish was a young pitcher about to age into his prime and Wilson was older and exiting his. He didn’t pay attention to Darvish having a deeper arsenal of pitches. He didn’t pay attention to reality at all. The Rangers hadn’t fallen in love with an ideal; it was Cowherd who had fallen in love with his moronic theory. I guess I don’t have to add that in the 14 months since Texas made its decision–one based on scouting, data and analysis–Darvish has proven to be one of the best pitchers in MLB while Wilson has faltered badly for his new team. And this isn’t just the exception with Cowherd–it’s the rule.

Cowherd doesn’t limit his foolishness to sports–he also makes gross and insulting generalizations about women and anyone he feels isn’t as successful as he is, though your definition of “successful” may differ. The suits at the sports network are obviously bright enough to realize what a huge douche they have working for them. But they only care about one thing: Can we turn him into a star and make money from his noise?

Of course, this is just a sports guy and sports aren’t important. But the same holds true for media across all areas in this country, especially in our age of dwindling financial returns for traditional platforms. When Jeff Zucker became the new head of CNN, he promised that he would “broaden the definition of what news is.” That remark won him applause from Rupert Murdoch, who has been poisoning the air with non-news and dubious research methods for decades. Murdoch has always believed that news is just another form of entertainment. Perhaps its just a coincidence that CNN and News Corp. properties were fast and first and embarrassingly wrong in the aftermath of the horrendous Boston Marathon carnage.

Proud jughead Joe Scarborough was able to cherry-pick polls that helped him sell dishonest stories in the run-up to the Presidential election, while questioning the integrity of pollster Nate Silver, who stuck to the numbers. The facts didn’t matter.

These aren’t crazy conspiracy theorists like Alex Jones–the single biggest sack of shit in American media–but in some ways their dishonesty is more dangerous. It isn’t cloaked in extremism but in respectability. And there’s nothing respectable about it.

The opening of Colin McGowan’s new article about the cartoonish Cowherd at the Classical:

“This past Friday, Colin Cowherd sat down with Bill Simmons to talk mostly about Colin Cowherd. They also kicked around a few theories about the mutation of LeBron’s competitiveness gene and the link between fascism and food. In tone, the podcast is more or less what one would expect: two hip-shooters a-hip-shootin’, and some excessive mutual admiration—Cowherd talks about Simmons’s perspective and craft as if Simmonsian should join Kafkaesque as an OED-approved literary adjective; Simmons gushes over Cowherd’s ability to… talk to himself for nine minutes at a time. For my part, I cleaned my apartment and occasionally yelled ‘wrong!’ from across the room.

I listened to the interview because I’m not looking to set my brain on fire with intellectual stimulation while drinking gin and scrubbing cat piss out of my bathroom floor on a Friday evening, but also because I wanted to listen to two powerful media figures I dislike talk shop. I think both Cowherd and Simmons, in their own ways, are what’s wrong with sports media, which in turn makes for an increasingly facile and (in Cowherd’s case) needlessly hostile mainstream sports discourse. I’ve called Simmons ‘either a hack or a complete asshole,’ and Cowherd, along with his louder, more malignant cousin Skip Bayless, isn’t in the sports business so much as he’s in the infuriation business. He peddles haughty reductiveness and calls it honesty, then bats around an overmatched simpleton from Steak’s Landing, Wisconsin for a few minutes before returning to his now-basically-show-long rant about Carmelo Anthony’s facial expressions and how, he doesn’t care what you think, he’s gonna go on pronouncing it ‘jih-roh.’

The podcast isn’t uninteresting, which Cowherd might claim is the entire battle. He exclaims at one point ‘What’s wrong with being interesting?’ which is exactly the sort of unassailable bully logic he employs on his radio show. Of course there is obviously nothing wrong with being interesting—what with it being definitionally positive—but here, Cowherd isn’t talking about the Lakers’ playoff chances for the third time in four days or staging overrated/underrated debates about literally anything. He’s talking about himself, and why he is the way he is, what he believes in. This is engaging enough: Colin Cowherd the human being is unlike anyone I’ve ever met. If he wants to talk about what makes him strange, I’ll listen.

What makes him strange—wrong, but also strange—is that he sees a direct correlation between popularity and, if not quite quality, some inherent goodness.”

Tags: Colin Cowherd, Colin McGowan

I’m always happy to answer your emails, be they positive or negative.

______________________________

[redacted] 4:17 PM (1 hour ago)

to me

In your piece on Babe Ruth, you say there were’nt a lot of great players in the early decades, in part because of the color line. What racist nonsense! So you have to be black to be great? There were many many stars from the very beginning. Come to grips with your prejudiced thinking.

Darren D’Addario <afflictor1@gmail.com> 5:23 PM (40 minutes ago)

to [redacted]

Your dishonest argument (that I stated or suggested that you had to be black to be great) shows how bankrupt your position is. Baseball didn’t have a critical mass of tremendous talent in the game’s early years for a variety of reasons (the lack of good salaries, its raffish nature, the paucity of a minor-league system as we know it), but the color line certainly was a huge factor in watering down the game. If you don’t acknowledge that basic fact, perhaps you need to come to grips with your prejudiced thinking.

Robots, not humans, should be calling balls and strikes at every Major League Baseball game. It should have been this way for years. There was a sad reminder of the reluctance to automate this aspect of umpiring on Sunday night when Marty Foster ended the Tampa Bay-Texas game with one of the worst ball-and-strike calls imaginable.

Of course, we won’t be seeing the game utilizing computers to greater effect anytime soon. Commissioner Bud Selig and his inner circle have shown a shocking incompetence in regard to most of the key issues facing the game–instant replay, home-plate collisions, the untenable stadium situations of the A’s and the Rays, the Mets festering ownership crisis–procrastinating rather than acting. These failings have been papered over by the sport’s runaway profits, which have everything to do with the explosion of regional cable and its hunger for a quantity of family-friendly events that defy time-shifting, and little to do with anything in particular that Selig has done.

What are the arguments for not using software to call strikes? There is a tradition of catchers framing pitches, purists will say, which will be lost. A small sacrifice that will eliminate larger issues. You don’t want that much variance in the execution of the rules of any sport, with the egos of the least-important “participants” taking center stage. A loose application of rules also opens up the possibility of officials tilting games for illicit purposes (not the case with the Foster call, of course). And inconsistent outcomes due to human error is one of the reasons why boxing has seen such a decline. (Knowledge of the impact of head injuries has been just as damaging, thinning the ranks of talent.) Professional basketball’s referee scandal of a few years back occurred because the rules of the game allow for far too much interpretation. That needn’t be the case with baseball.

The human element will be lost, the stalwarts argue, not acknowledging that baseball is not some pastoral pastime but a multibillion dollar industry, and one that can easily afford to ensure its integrity if it weren’t for the lethargy and myopia of its highest ranks.•

Tags: Bud Selig

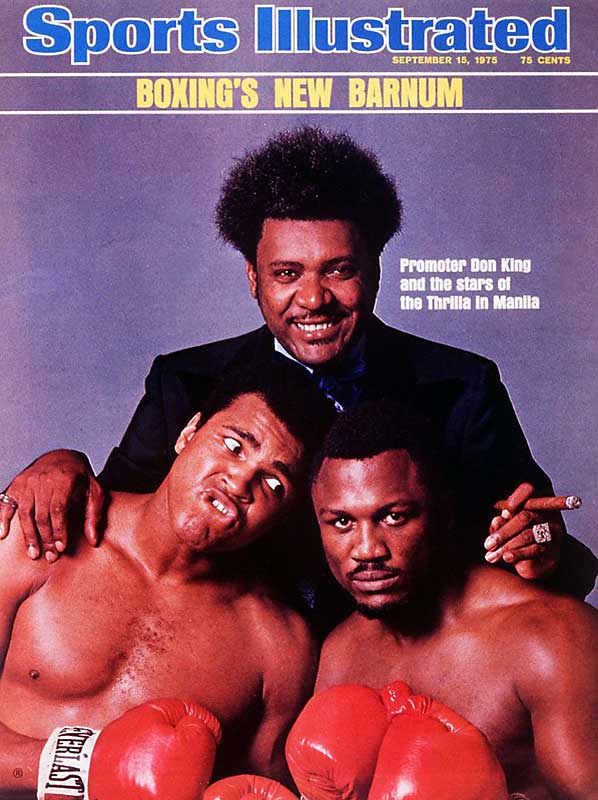

There are plenty of legitimate reasons to dislike Don King, the boxing promoter in decline. He’s a liar and a manipulator and, worst of all, he coldly discarded the very boxers who sacrificed their health for his bottom line, treating them like so many disposable commodities. But none of those character flaws are the main thing that made him so reviled at his apex. He was hated because he dared to be black and a capitalist in an age before rappers perfected the greed-is-good ethos. He didn’t aspire to be twice as good as his white counterparts as African-Americans are often expected to be, but instead hustled his way into the money game, bending and breaking its protean rules, gleefully pointing out that his hands were no dirtier than anyone else’s, just darker. Only in America.

The opening of “The End of Don King,” Jay Caspian Kang’s excellent new Grantland profile of the former national figure in his dotage:

“In the back room of Manhattan’s Carnegie Deli, Don King picked at a pastrami sandwich with his fingers. He had just been asked a question about his electric hair and, for the first time in a day filled with radio and television interviews, King paused before he spoke. A cautious look crept over his graying eyes. As he silently deliberated between several well-worn origin myths about the height of that hair, King tweezed a scrap of pastrami between two well-manicured fingernails and dragged the meat through a puddle of deli mustard. ‘My hair is God’s aura,’ King explained while chewing. ‘Everything went up when I got home from the penitentiary. One night I went to lie down next to my wife and my hair started popping and uncurling all on its own — ping, ping, ping, ping! I knew that it was God telling me to stay on the righteous path so he could one day pull me up to be there with him.”

King smiled, but not the smile you remember. That smile — the screwed-on mask of boundless optimism — had been on full display throughout this week of promotions, but at the Carnegie, King had finally succumbed to exhaustion. ‘When I’m doing good, the hair goes straight up,’ King said, a bit wearily. ‘Now that things are difficult, the hair has gotten a little flatter.’

I had been trailing Don King for two weeks between Boca Raton, Florida, and now New York City. This was the closest he had come to admitting that things just weren’t what they used to be. In three days’ time, Tavoris ‘Thunder’ Cloud, King’s last fighter of any consequence, would step into the ring against Bernard Hopkins at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn. The story of the fight should have been about the 48-year-old Hopkins and his quest to become the oldest champion in boxing history. But because Don King was involved, the focus during fight week had been on Don King and his uncertain future. If Cloud lost to Hopkins — especially in a boring way — his short career as an opponent in televised events would be put in serious jeopardy and King would have very little left to promote. In a pre-fight interview, Hopkins, who, like so many other fighters, had worked with King before an inevitable falling-out, had this to say about his old promoter: ‘What a way to put the last nail in the coffin. Who thought it would be me that would shut him down?’

At the Carnegie, nobody was talking much about Tavoris Cloud or Bernard Hopkins or the impending end of Don King Promotions. King had come to one of his favorite New York landmarks to enjoy a quiet lunch with three longtime employees. They talked, mostly, about music and old times in Manhattan, the city where King lived and worked during the majority of his reign at the top of boxing. The conversation eventually turned to James Brown. Don King, still digging his fingers into his sandwich, muttered, ‘James Brown died owing me $50,000. But I loved James Brown.'”

Tags: Don King, Jay Caspian Kang

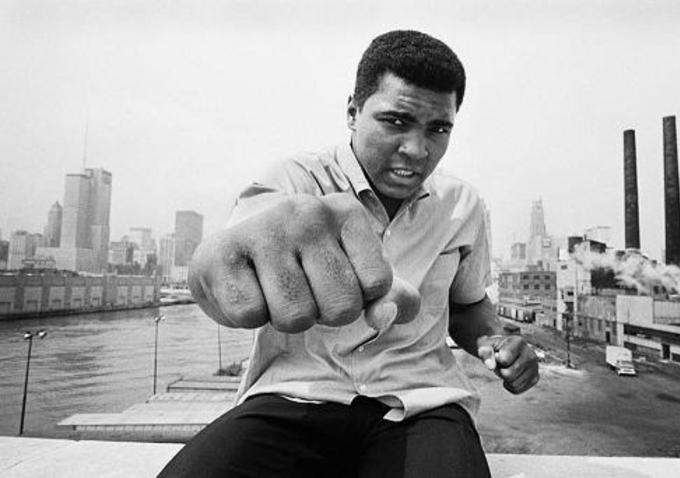

Muhammad Ali visits with Dick Cavett in 1978 in the wake of his loss to Leon Spinks. Ali, now slowed and beloved, would win a rematch in his final great moment as a boxer, but he really, really should have been retired for several years at this point.

Tags: Dick Cavett, Muhammad Ali

Because all the poor people finally have sufficient food and shelter, we felt it was now appropriate to invent a hovercraft golf cart. I wish this were an April Fool’s Day joke, but it appears to be real. After a relaxing nine holes, let’s go to potter’s field and dig up dead beggars and use their bones to batter the current beggars.

Tags: Bubba Watson

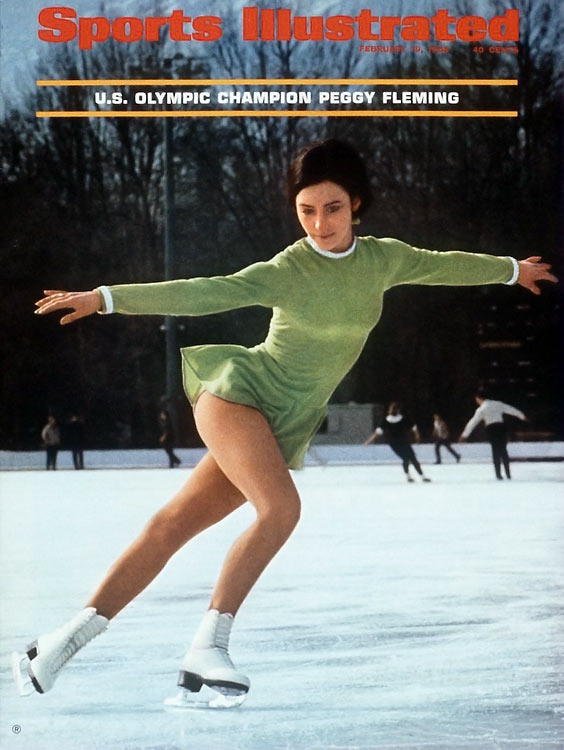

Figure skater Peggy Fleming was rewarded for her gold medal at the 1968 Olympics by getting to visit Joe Namath’s short-lived talk show the following year, enduring the host’s fu manchu and bell-bottoms and Paul Anka’s attempts at singing. Namath was actually a capable interviewer and conducted more natural and engaging conversations than the large majority of today’s late-night hosts. Dick Schapp plays the affable sidekick.

Tags: Dick Schapp, Joe Namath, Paul Anka', Peggy Fleming

From “Creating the All-Terrain Human,” Christopher Solomon’s New York Times profile of Kilian Jornet Burgada, an ultra-athlete whose body operates more as machine than human:

“Kilian Jornet Burgada is the most dominating endurance athlete of his generation. In just eight years, Jornet has won more than 80 races, claimed some 16 titles and set at least a dozen speed records, many of them in distances that would require the rest of us to purchase an airplane ticket. He has run across entire landmasses (Corsica) and mountain ranges (the Pyrenees), nearly without pause. He regularly runs all day eating only wild berries and drinking only from streams. On summer mornings he will set off from his apartment door at the foot of Mont Blanc and run nearly two and a half vertical miles up to Europe’s roof — over cracked glaciers, past Gore-Tex’d climbers, into the thin air at 15,781 feet — and back home again in less than seven hours, a trip that mountaineers can spend days to complete. A few years ago Jornet ran the 165-mile Tahoe Rim Trail and stopped just twice to sleep on the ground for a total of about 90 minutes. In the middle of the night he took a wrong turn, which added perhaps six miles to his run. He still finished in 38 hours 32 minutes, beating the record of Tim Twietmeyer, a legend in the world of ultrarunning, by more than seven hours. When he reached the finish line, he looked as if he’d just won the local turkey trot.” (Thanks Browser.)

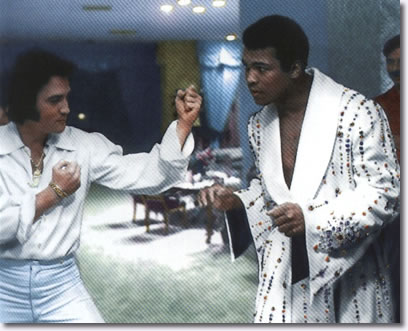

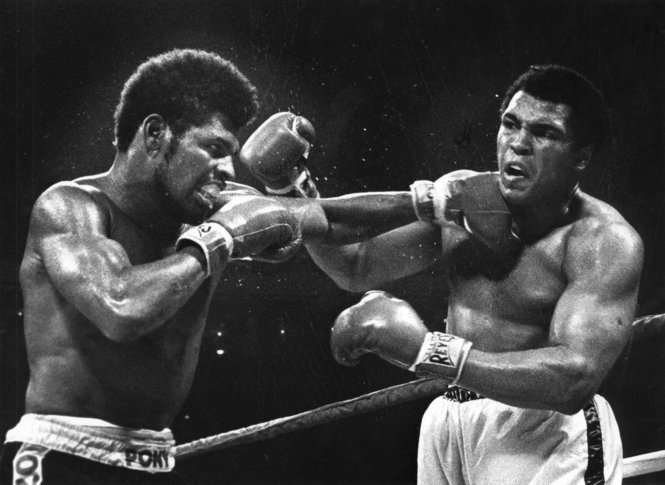

Muhammad Ali came close to boxing the ears of Joe Namath during a 1969 installment of the talk show hosted by the Jets quarterback. This was during the period when the boxer when the boxer had been stripped of the heavyweight championship for refusing to serve in the U.S. military, and he was in no mood. Oh, and George Segal and his facial hair dropped by.

Tags: Dick Schapp, George Segal, Joe Namath, Muhammad Ali

Wilt Chamberlain was a remarkable athlete (basketball, volleyball, track and field), but it’s probably a good thing he never realized his dream to fight Muhammad Ali. Howard Cosell presides over the ridiculousness, as he often did.

From East Side Boxing: “Springtime, 1971. Inside an office within the Houston Astrodome, a most unusual negotiation is about to take place. Seated at one end of the table is Muhammad Ali, former Heavyweight Champion of the World and self-proclaimed greatest fighter of all time. Next to him: Bob Arum, the former Justice Department attorney turned boxing promoter who had worked with Ali since his 1966 fight with George Chuvalo.

A few minutes later, they are joined by one of the most imposing figures in all of sport, the towering titan of professional basketball Wilt Chamberlain. Ali and Chamberlain knew each other well and had appeared together on numerous occasions in the past, from television talk shows to press conferences addressing civil rights issues. The purpose of this meeting, however, was far different from their previous encounters.

Today no media cameras are present, no reporters scramble for sound bites. The two most famous athletes in the world isolated themselves within the cavernous empty stadium to quietly discuss an event without precedent in the annals of sport. For on this day, Muhammad Ali and Wilt Chamberlain will agree to face each other in a 15-round boxing match, to be held in the Astrodome on July 26, 1971.

For Chamberlain, fighting Ali represented the pinnacle in his quest to conquer not only his own sport, but the entire sporting world.”

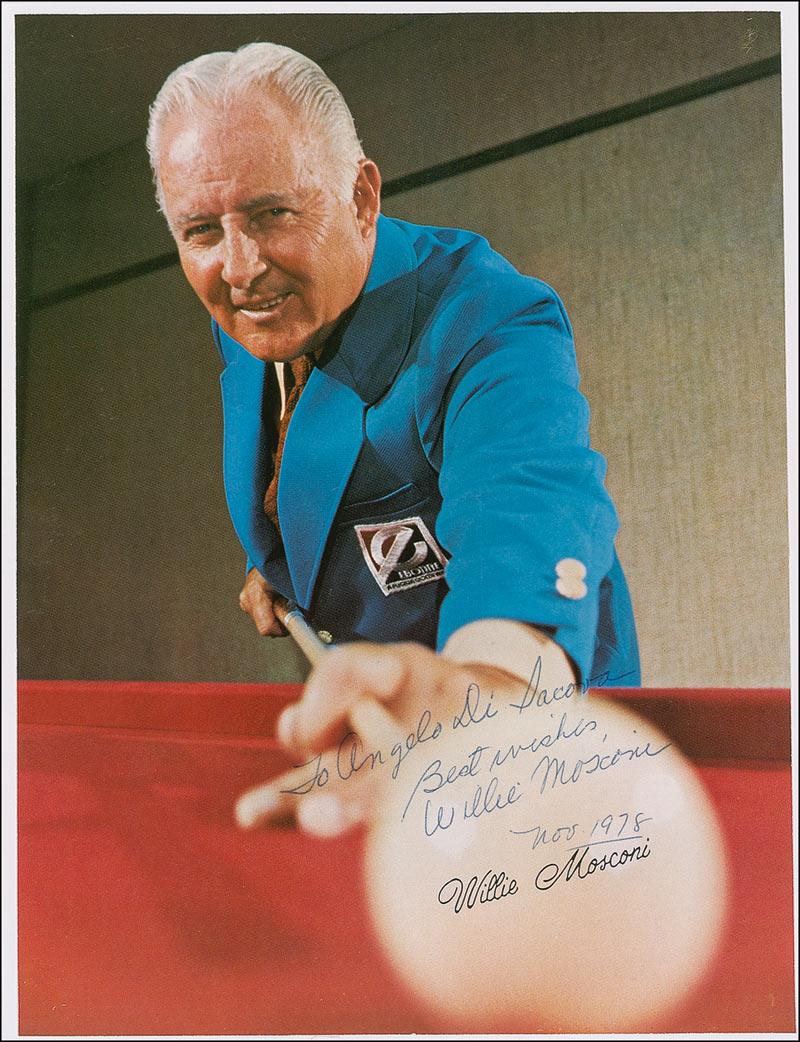

Willie Mosconi, spinning in his grave.

Remember when I wrote that I fear an NFL player is going to die during a game because of how dangerous the sport has become? Well, Commissioner Roger Goodell has similar apprehensions. From “His Game, His Rules,” Don Van Natta Jr.’s excellent ESPN profile of Goodell’s iron-fisted tenure:

“Six and a half years into Goodell’s tenure, his billionaire bosses believe the man who dreamed of being commissioner as a teenager is perfectly suited to lead the league through its most perilous time. They paid him $29.5 million in 2011, and in January 2012 he signed a five-year contract extension. Robert Kraft, the Patriots owner, says Goodell runs the NFL as if he owns it — the league literally belongs to him. Jerry Jones, the Cowboys owner, says Goodell cares so much about the game that he ‘totally emptied his bucket — everything he’s got — and put his life into the NFL.’

As part of his mission, Goodell often tells audiences a favorite story: More than a century ago, before there was an NFL, President Theodore Roosevelt saved football with the blunt force of his visionary leadership. In 1904, 18 student-athletes died playing the game, mostly from skull fractures. A devout fan, Roosevelt convened the coaches from Harvard, Yale and Princeton to a White House meeting. The innovations that were adopted — the forward pass, the founding of the NCAA — helped propel an endangered game into the modern era.

The history lesson not only places Goodell in Roosevelt’s shoes and the current worries about player safety into a historical context, it also portends one of his greatest fears: An NFL player is going to die on the field.

It’s happened only once. Lions wide receiver Chuck Hughes died of a heart attack late in a game on Oct. 24, 1971. Within the past year, Goodell has told friends privately that he believes if the game’s hard-knocks culture doesn’t change, it could happen again. ‘He’s terrified of it,’ says a Hall of Fame player who speaks regularly with Goodell. ‘It wouldn’t just be a tragedy. It would be awfully bad for business.'”

Tags: Don Van Natta Jr., Roger Goodell