In writing disapprovingly in the New York Review of Books of Naomi Klein’s “This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate,” Elizabeth Kolbert points out that the truth about climate change isn’t only inconvenient, it’s considered a deal-breaker, even by the supposedly green. An excerpt follows.

_____________________________

What would it take to radically reduce global carbon emissions and to do so in a way that would alleviate inequality and poverty? Back in 1998, which is to say more than a decade before Klein became interested in climate change, a group of Swiss scientists decided to tackle precisely this question. The plan they came up with became known as the 2,000-Watt Society.

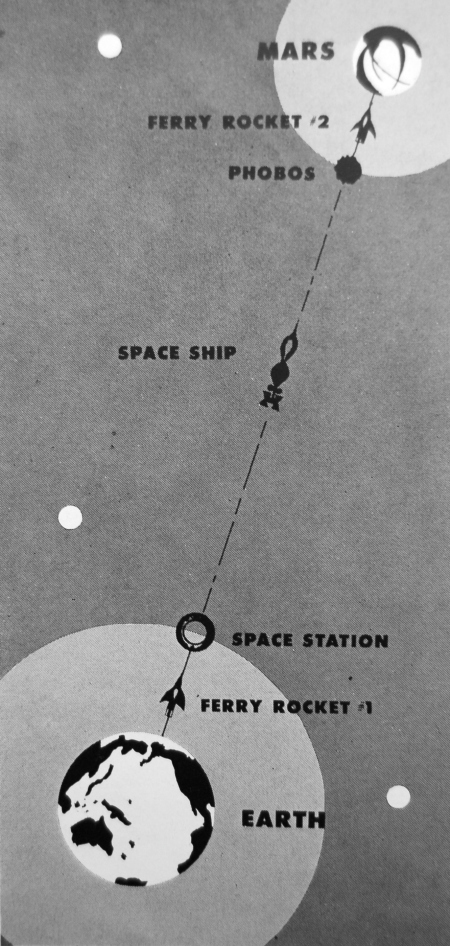

The idea behind the plan is that everyone on the planet is entitled to generate (more or less) the same emissions, meaning everyone should use (more or less) the same amount of energy. Most of us don’t think about our energy consumption—to the extent we think about it at all—in terms of watts or watt-hours. All you really need to know to understand the plan is that, if you’re American, you currently live in a 12,000-watt society; if you’re Dutch, you live in an 8,000-watt society; if you’re Swiss, you live in a 5,000-watt society; and if you’re Bangladeshi you live in a 300-watt society. Thus, for Americans, living on 2,000 watts would mean cutting consumption by more than four fifths; for Bangladeshis it would mean increasing it almost by a factor of seven.

To investigate what a 2,000-watt lifestyle might look like, the authors of the plan came up with a set of six fictional Swiss families. Even those who lived in super energy-efficient houses, had sold their cars, and flew very rarely turned out to be consuming more than 2,000 watts per person. Only “Alice,” a resident of a retirement home who had no TV or personal computer and occasionally took the train to visit her children, met the target.

The need to reduce carbon emissions is, ostensibly, what This Changes Everything is all about. Yet apart from applauding the solar installations of the Northern Cheyenne, Klein avoids looking at all closely at what this would entail. She vaguely tells us that we’ll have to consume less, but not how much less, or what we’ll have to give up. At various points, she calls for a carbon tax. This is certainly a good idea, and one that’s advocated by many economists, but it hardly seems to challenge the basic logic of capitalism. Near the start of the book, Klein floats the “managed degrowth” concept, which might also be called economic contraction, but once again, how this might play out she leaves unexplored. Even more confoundingly, by end of the book she seems to have rejected the idea. “Shrinking humanity’s impact or ‘footprint,’” she writes, is “simply not an option today.”

In place of “degrowth” she offers “regeneration,” a concept so cheerfully fuzzy I won’t even attempt to explain it. Regeneration, Klein writes, “is active: we become full participants in the process of maximizing life’s creativity.”

To draw on Klein paraphrasing Al Gore, here’s my inconvenient truth: when you tell people what it would actually take to radically reduce carbon emissions, they turn away. They don’t want to give up air travel or air conditioning or HDTV or trips to the mall or the family car or the myriad other things that go along with consuming 5,000 or 8,000 or 12,000 watts. All the major environmental groups know this, which is why they maintain, contrary to the requirements of a 2,000-watt society, that climate change can be tackled with minimal disruption to “the American way of life.” And Klein, you have to assume, knows it too. The irony of her book is that she ends up exactly where the “warmists” do, telling a fable she hopes will do some good.•