As long as there are movies, I think we’ll watch Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, which boldly aimed to journey beyond the stars, to second-guess the future, and remarkably pulled it all off. Keir Dullea, the actor who portrayed astronaut Dave Bowman, just did a HAL-centric AMA at Reddit. A few exchanges follow.

_________________________________

Question:

What is something people misunderstand or misinterpret about Kubrick?

Keir Dullea:

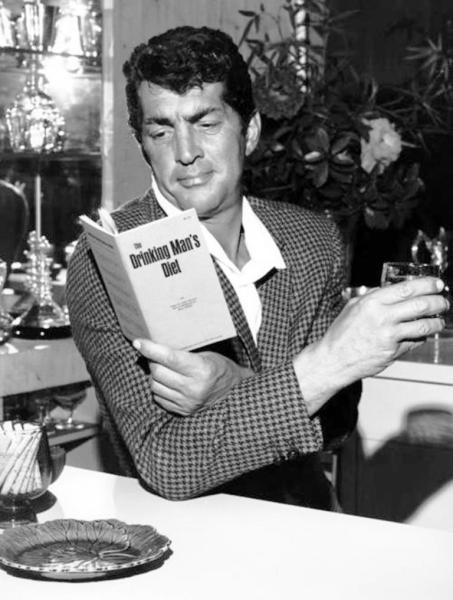

I’m often asked: Was Kubrick a task master? The answer is no; anything but. He never raised his voice, he had a quiet droll sense of humor and was a man with great curiosity.

_________________________________

Question:

What preparation or research did you do before filming 2001? Did Kubrick give you any insight into how the character should be portrayed, or did he give you freedom to explore that?

Keir Dullea:

Not a lot. Don’t forget, Arthur C. Clarke, who, aside from being the great writer that he was, was a scientist in his own right and was able to portray the future in such a specific way that the script in itself gave us everything we needed.

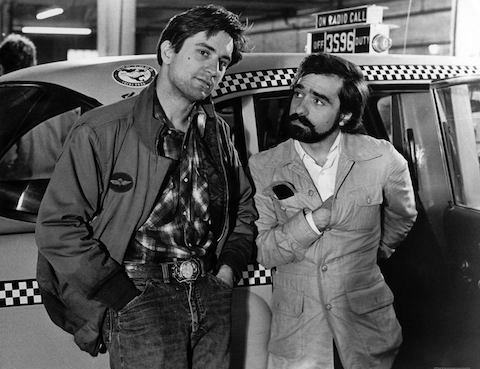

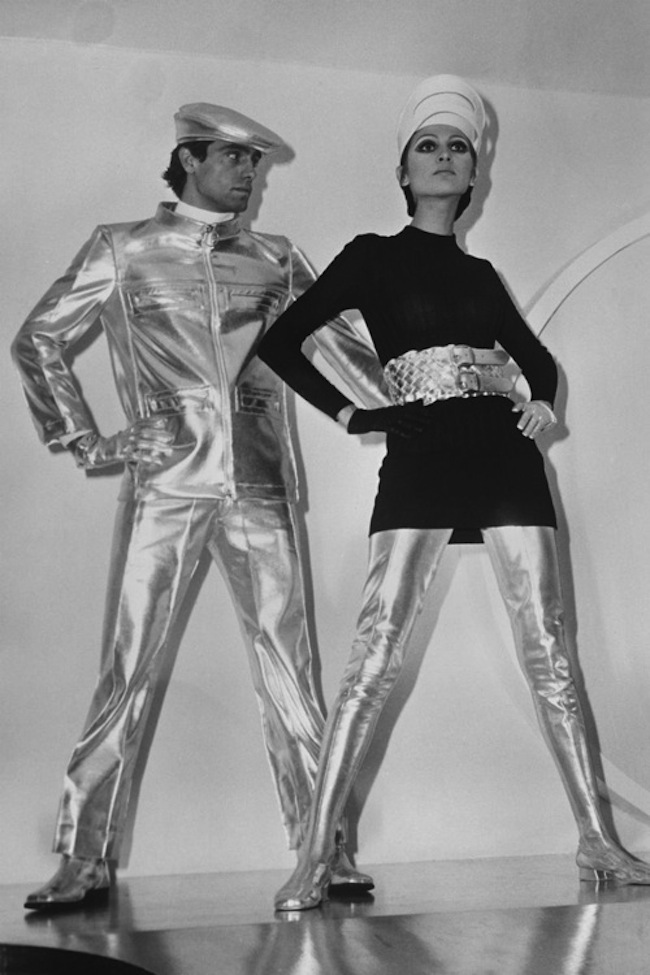

The only suggestion Kubrick gave overall was that he did not want us to portrayal scientists in the way they had been portrayed in grade B science fiction movies of the past, that is, men with goatees and outlandish clothes, speaking in some kind of pseudo babble.

One of the definitions I think of a great director is that they cast greatly. If you cast very well, and Stanley being the genius that he was did that in all his films, you don’t need to do a lot of direction, just give the actors the relaxation and space that they need and they will come through.

_________________________________

Question:

What was your favorite scene you participated in?

Keir Dullea:

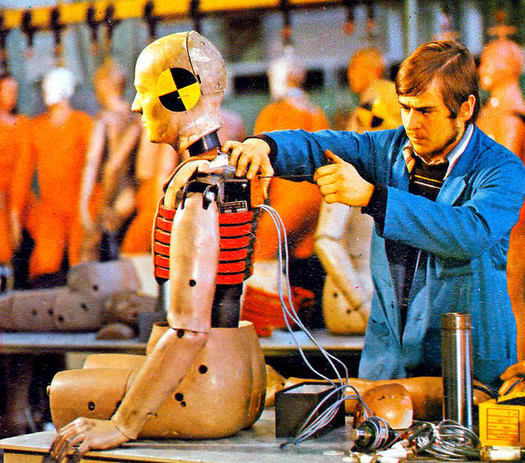

I think my favorite scene was where I’m dismantling HAL’s brain. It reminded me a bit of a famous movie and also play called Of Mice and Men when Lenny is speaking with George regarding their plans to start a farm. This is a scene that comes at the end of the film after Lenny has indadvertedly caused the death of a young woman. Now there’s a posse that is looking for him intending possibly to string him up. This discussion of their plans to start a farm has been heard throughout the film, and so with some love and compassion, with a hidden pistol behind his back George reviews their plans with Lenny and half-way through their discussion he shoots him behind his back to avoid him being killed by a posse of men. In some way, emotionally, that scene from Of Mice and Men affected the way I played the scene with HAL.

_________________________________

Question:

Kubrick was a notorious perfectionist. Do you have any interesting anecdotes about that?

Keir Dullea:

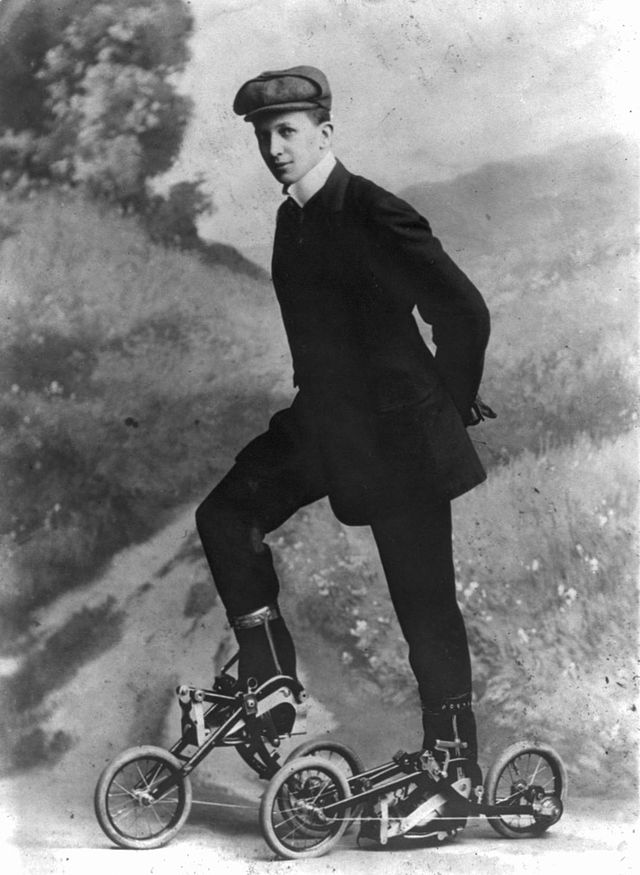

On the first day of shooting, Stanley noticed my shoes and felt they weren’t right. We stopped shooting for the rest of the day until they found the right pair. Let’s face it, feet don’t play a huge role in films.

_________________________________

Question:

What is your favorite sci-fi movie?

Keir Dullea:

2001: A Space Odyssey.

Question:

APART FROM 2001 … what is your favorite sci-fi movie?

Do you enjoy the genre apart from being one of its greatest exponents?

Keir Dullea:

Yes, I enjoy sci-fi and Blade Runner is my other favorite of the genre.•

____________________________

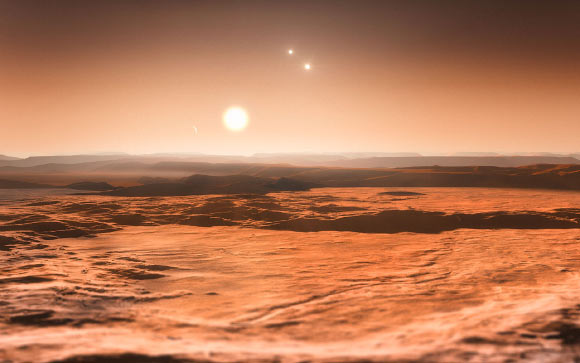

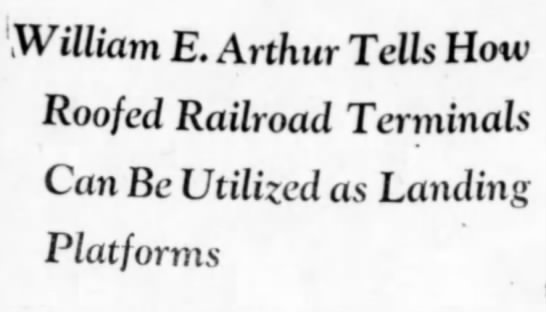

“Out here among the stars lies the destiny of mankind”: