In the podcast conversation between Russ Roberts and Gary Marcus, the latter mentions the 1960s computer “psychotherapist” Eliza. Here’s a repost from a year ago about the pre-Siri shrink.

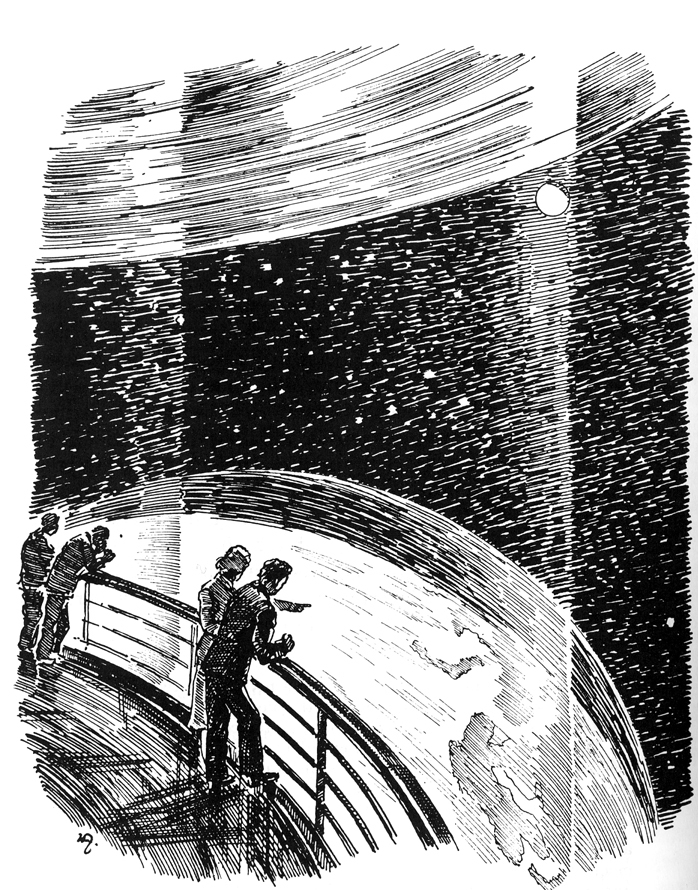

The real shift in our time isn’t only that we’ve stopped worrying about surveillance, exhibitionism and a lack of privacy, but that we’ve embraced these things–demanded them, even. There must have been something lacking in our lives, something gone unfulfilled. But is this intimacy with technology and the sense of connection and friendship and relationship that attends it–often merely a likeness of love–an evolutionary correction or merely a desperate swipe in the wrong direction?

The opening of Brian Christian’s New Yorker piece about Spike Jonze’s Her, a film about love in the time of simulacra, in which a near-future man is wowed by a “woman” who seems to him like more than just another pretty interface:

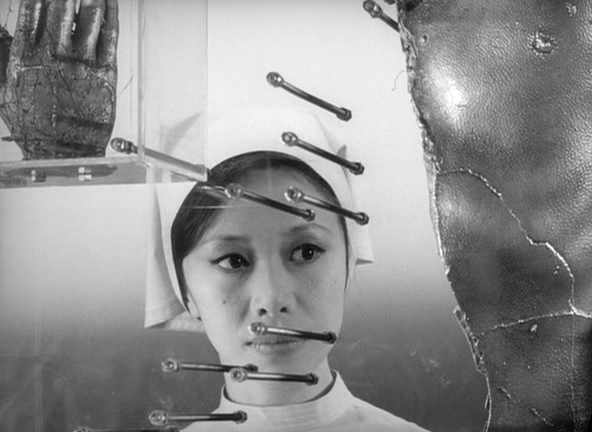

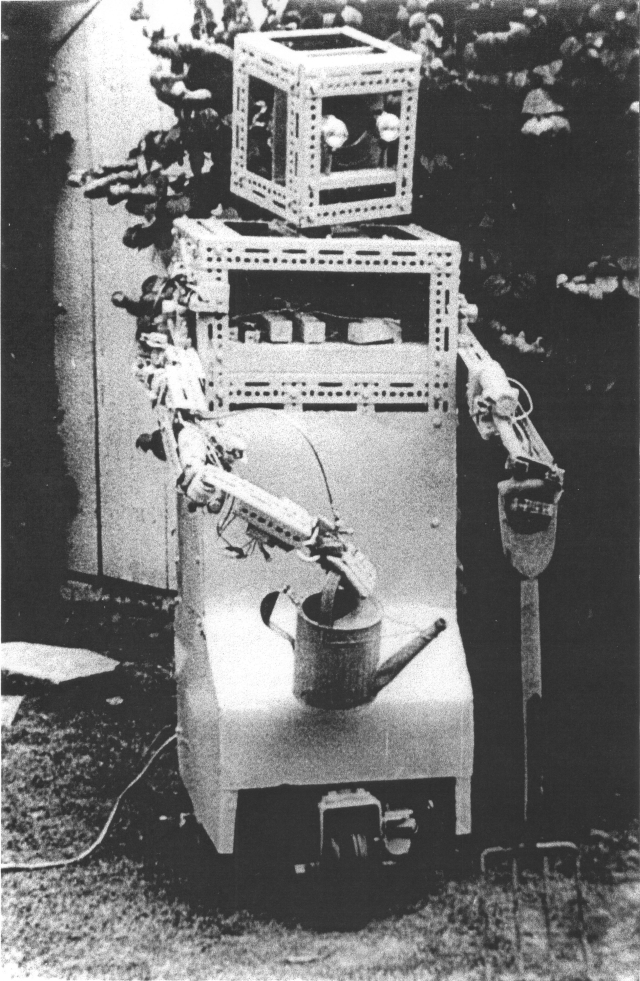

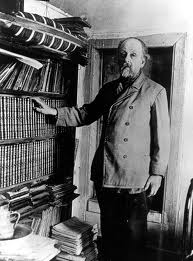

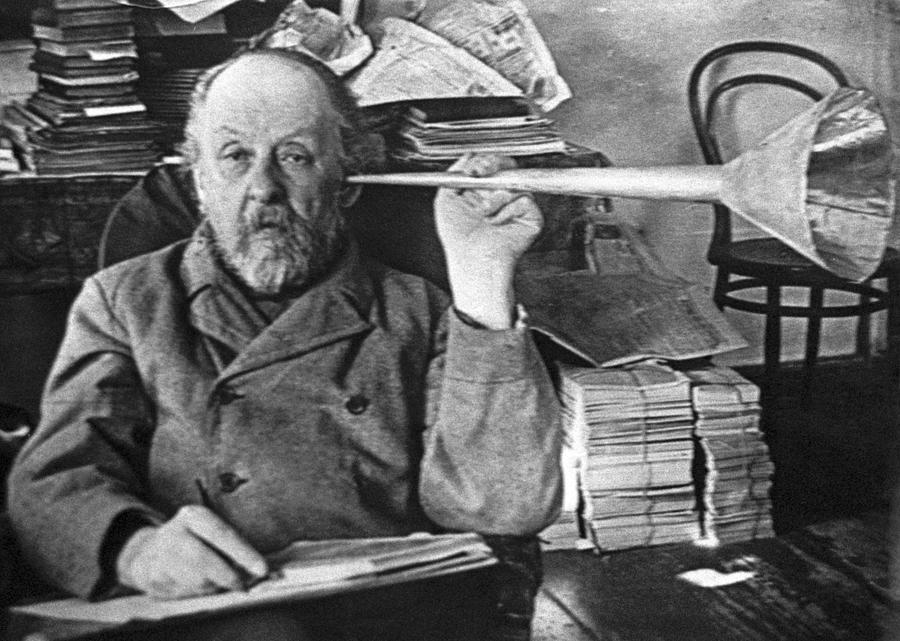

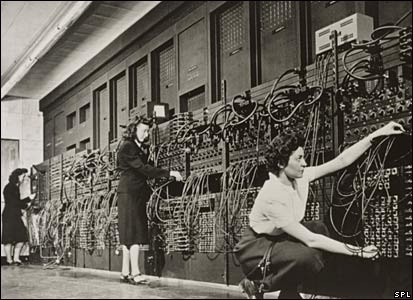

“In 1966, Joseph Weizenbaum, a professor of computer science at M.I.T., wrote a computer program called Eliza, which was designed to engage in casual conversation with anybody who sat down to type with it. Eliza worked by latching on to keywords in the user’s dialogue and then, in a kind of automated Mad Libs, slotted them into open-ended responses, in the manner of a so-called non-directive therapist. (Weizenbaum wrote that Eliza’s script, which he called Doctor, was a parody of the method of the psychologist Carl Rogers.) ‘I’m depressed,’ a user might type. ‘I’m sorry to hear you are depressed,’ Eliza would respond.

Eliza was a milestone in computer understanding of natural language. Yet Weizenbaum was more concerned with how users seemed to form an emotional relationship with the program, which consisted of nothing more than a few hundred lines of code. ‘I was startled to see how quickly and how very deeply people conversing with DOCTOR became emotionally involved with the computer and how unequivocally they anthropomorphized it,’ he wrote. ‘Once my secretary, who had watched me work on the program for many months and therefore surely knew it to be merely a computer program, started conversing with it. After only a few interchanges with it, she asked me to leave the room.’ He continued, ‘What I had not realized is that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people.’

The idea that people might be unable to distinguish a conversation with a person from a conversation with a machine is rooted in the earliest days of artificial-intelligence research.”