Ed Finn of Slate has a new interview with Margaret Atwood, and in one give-and-take she explains her philosophy on writing about the future. An excerpt:

Question:

Whether you call it science fiction or speculative fiction, much of your work imagines a future that many of us wouldn’t want. Do you see stories as a way to effect change in the world, especially about climate change?

Margaret Atwood:

I think calling it climate change is rather limiting. I would rather call it the everything change because when people think climate change, they think maybe it’s going to rain more or something like that. It’s much more extensive a change than that because when you change patterns of where it rains and how much and where it doesn’t rain, you’re also affecting just about everything. You’re affecting what you can grow in those places. You’re affecting whether you can live there. You’re affecting all of the species that are currently there because we are very water dependent. We’re water dependent and oxygen dependent.

The other thing that we really have to be worried about is killing the oceans, because should we do that there goes our major oxygen supply, and we will wheeze to death.

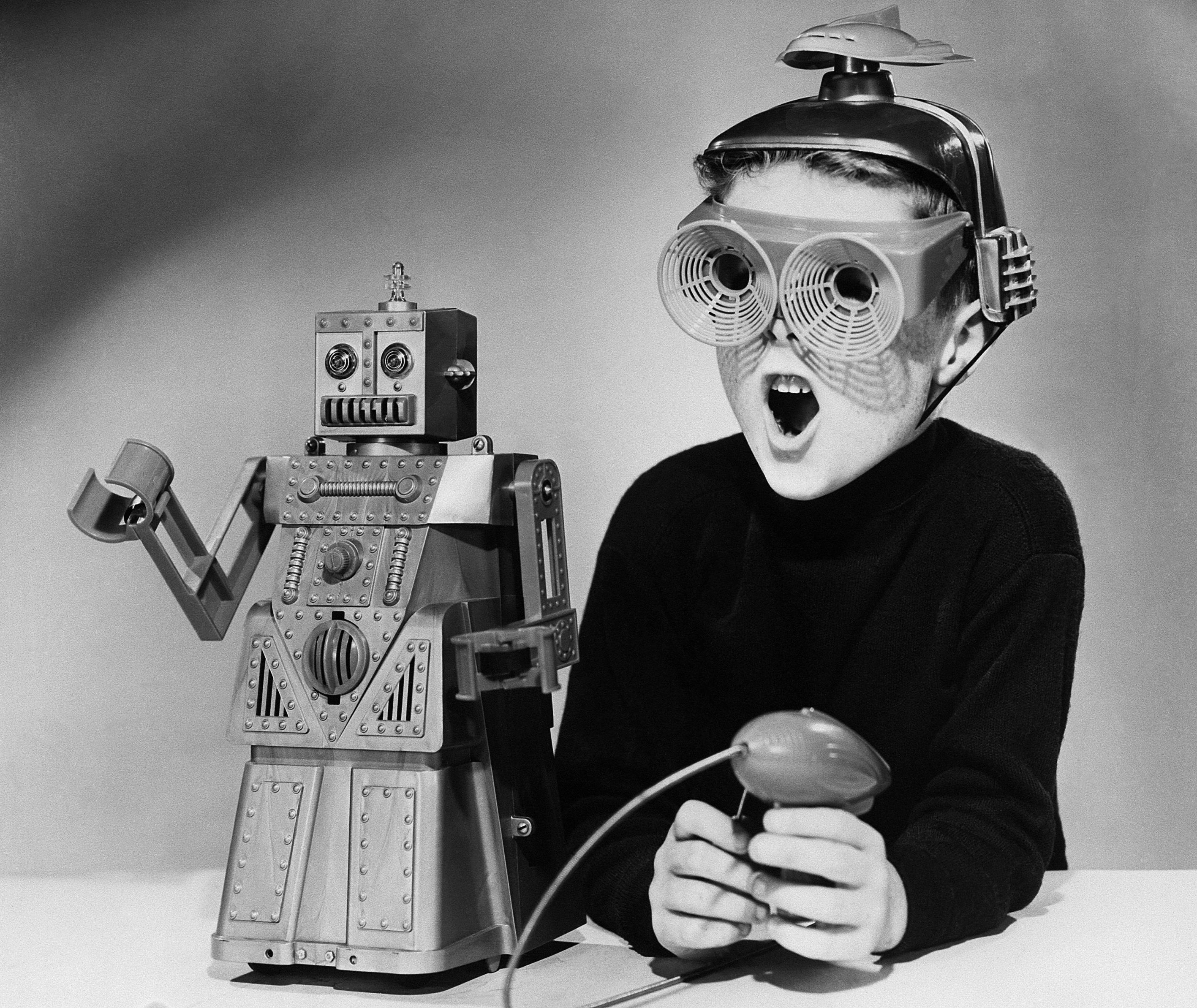

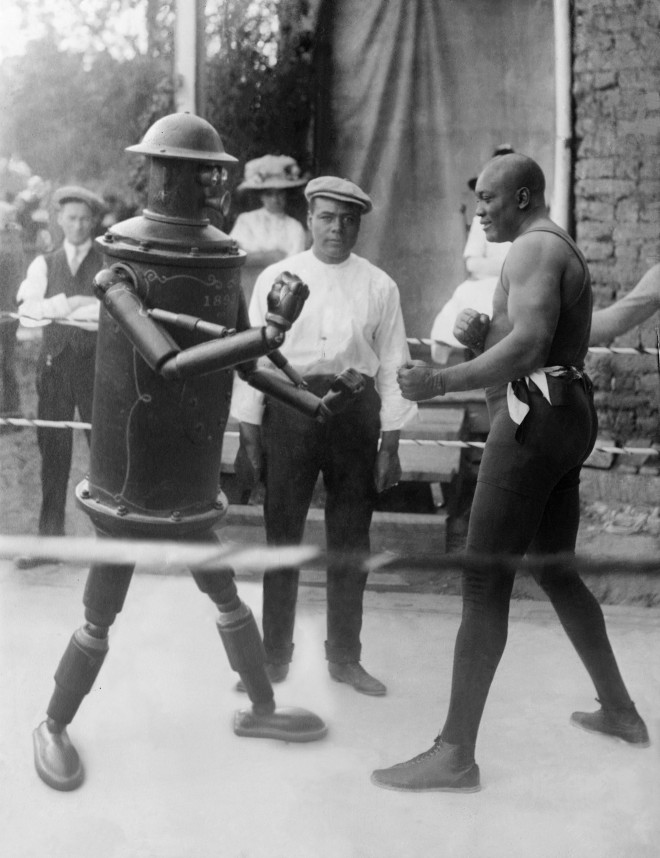

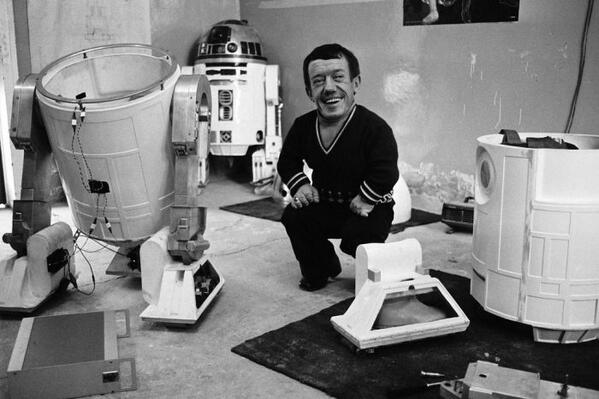

It’s rather useless to write a gripping narrative with nothing in it but climate change because novels are always about people even if they purport to be about rabbits or robots. They’re still really about people because that’s who we are and that’s what we write stories about.

You have to show people in the midst of change and people coping with change, or else it’s the background. In the MaddAddam books, people hardly mentioned “climate change,” but things have already changed. For instance, in the world of Jimmy who we follow in Oryx and Crake, the first book, as he’s growing up as an adolescent, they’re already getting tornadoes on the East Coast of the United States, the upper East Coast, because I like setting things in and around Boston. It’s nice and flat, and when the sea rises a bunch of it will flood. It’s the background, but it’s not in-your-face a sermon.

When you set things in the future, you’re thinking about all of the same things as the things that you’re thinking about when you’re writing historical fiction. But with the historical fiction, you’ve got more to go on, and you also know that people are going to be checking up on your details. If you put the wrong underpants on Henry VIII, you’re in trouble.•