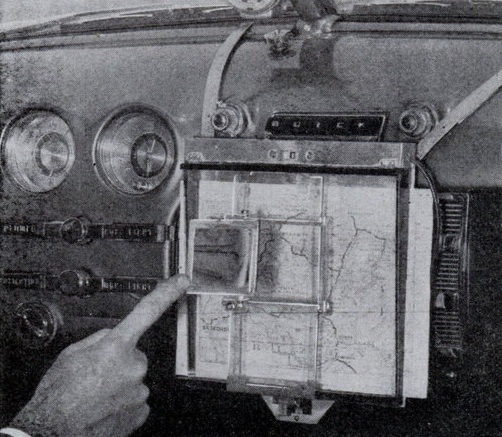

In a recent episode of EconTalk, host Russ Roberts invited journalist Adam Davidson of the New York Times to discuss, among other things, his recent article “What Hollywood Can Teach Us About the Future of Work.” In this “On Money” column, Davidson argues that short-term Hollywood projects–a freelance, piecemeal model–may be a wave of the future. The writer contends that this is better for highly talented workers and worrisome for the great middle. I’ll agree with the latter, though I don’t think the former is as uniformly true as Davidson believes. In life, stuff happens that talent cannot save you from, that the market will not provide for.

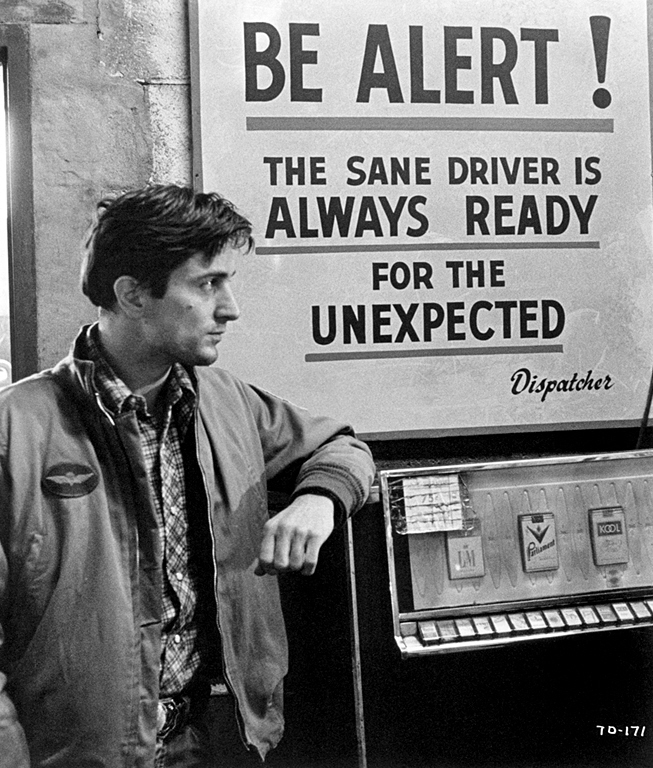

What really perplexed me about the program was the exchange at the end, when the pair acknowledges being baffled by Uber’s many critics. I sort of get it with Roberts. He’s a Libertarian who loves the unbridled nature of the so-called Peer Economy, luxuriating in a free-market fantasy that most won’t be able to enjoy. I’m more surprised by Davidson calling Uber a “solution” to the crisis of modern work, in which contingent positions have replaced FT posts in the aftermath of the 2008 financial collapse. You mean it’s a solution to a problem it’s contributed to? It seems a strange assertion given that Davidson has clearly demonstrated his concern about the free fall of the middle class in a world in which rising profits have been uncoupled from hiring.

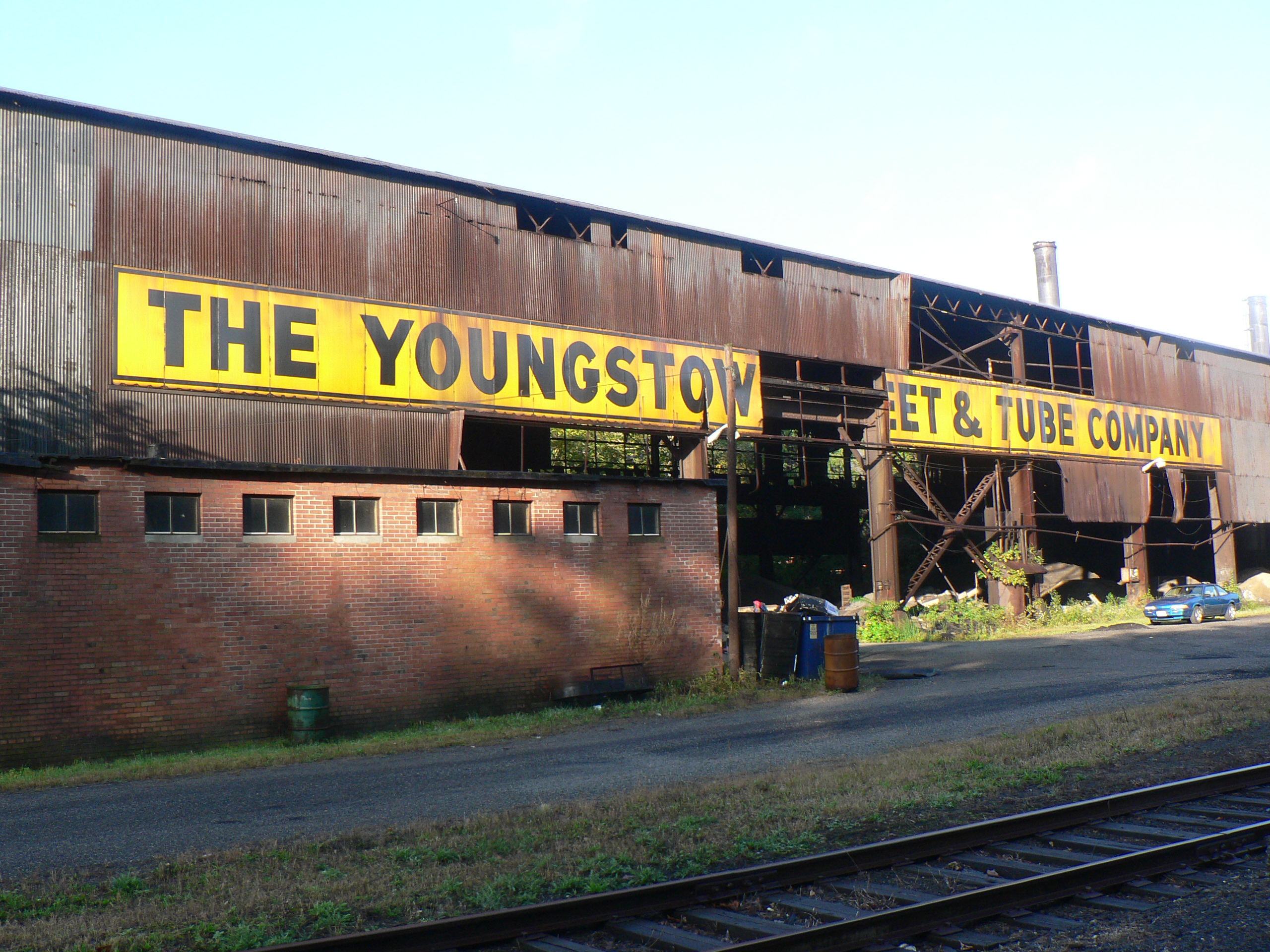

The reason why Uber is considered an enemy of Labor is because Uber is an enemy of Labor. Not only are medallion owners and licensed taxi drivers (whose rate is guaranteed) hurt by ridesharing, but Uber’s union-less drivers are prone to pay decreases at the whim of the company (which may be why about half the drivers became “inactive”–quit–within a year). And the workers couldn’t be heartened by CEO Travis Kalanick giddily expressing his desire to be rid of all of them before criticism intruded on his obliviousness, and he began to pretend to be their champion for PR purposes.

The Sharing Economy (another poor name for it) is probably inevitable and Uber and driverless cars are good in many ways, but they’re not good for Labor. If Roberts wants to tell small-sample-size stories about drivers he’s met who work for Uber just until their start-ups receive seed money and pretend that they’re the average, so be it. The rest of us need to be honest about what’s happening so we can reach some solutions to what might become a widespread problem. If America’s middle class is to be Uberized, to become just a bunch of rabbits to be tasked, no one should be satisfied with the new normal.

From EconTalk:

Russ Roberts:

A lot of people are critical of the rise of companies like Uber, where their workforce is essentially piece workers. Workers who don’t earn an annual salary. They’re paid a commission if they can get a passenger, if they can take someone somewhere, and they don’t have long-term promises about, necessarily, benefits. They have to pay for their own car, provide their own insurance, and a lot of people are critical of that, and my answer is, Why do people do it if it’s so awful? That’s really important. But I want to say something slightly more optimistic about it which is a lot of people like Uber, working for Uber or working for a Hollywood project for six months, because when it’s over they can take a month off or a week off. A lot of the people I talk to who drive for Uber are entrepreneurs, they’re waiting for their funding to come through, they’re waiting for something to happen, and they might work 80 hours a week while they’re waiting and when the money comes through or when their idea starts to click, they’re gonna work five hours a week, and then they’ll stop, and they don’t owe any loyalty to anyone, they can move in and out of work as they choose. I think there’s a large group of people who really love that. And that’s a feature for many people, not a bug. What matters is–beside your satisfaction and how rewarding your life is emotionally in that world–your financial part of it depends on what you make while you’re working. It’s true it’s only sort of part-time, but if you make enough, and evidently many Uber drivers are former taxi drivers who make more money with Uber for example, if you make enough, it’s great, so it seems to me that if we move to a world where people are essentially their own company, their own brand, the captain of their own ship rather than an employee, there are many good things about that as long as they have the skills that are in demand that people are willing to pay for. Many people will unfortunately will not have those skills. It’s a serious issue, but for many people those are enormous pluses, not minuses.

Adam Davidson:

Yes, I agree with you. Thinking of life as an Uber driver with that as your only possible source of income, I would guess that might be tough. Price competition is not gonna be your friend. Thinking about a world where you have a whole bunch of options, including Task Rabbit, and who knows what else, Airbnb, to earn money in a variety of ways, that’s at various times and at various levels of intensity, that strikes me as only good. If we could shove that into the 1950s, I think you would have seen a lot more people leaving that corporate model and starting their own businesses or spending more time doing more creative endeavors. That all strikes me as a helpful tool. It does sound like some of the people who work at Uber have kind of been jerks, but it does seem strange to me that some people are mad at the company that’s providing this opportunity. It is tough that lots of Americans are underemployed and aren’t earning enough. That’s a bad situation, but it is confusing to me that we get mad at companies that are providing a solution.•