Rolltop, the laptop you can roll up. Just a concept at this point. Now if they can just teach the guy in the video how to remove the stick from his ass.

You are currently browsing the archive for the Science/Tech category.

A portrait of the scientist as a young child, from Carl Zimmer’s new profile of star astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson in Playboy:

“Tyson first saw the Milky Way when he was nine, projected across the ceiling of New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He thought it was a hoax. From the roof of the Skyview Apartments in the Bronx, where he grew up, he could only see a few bright stars. When Tyson turned eleven, a friend loaned him a pair of 7×35 binoculars. They weren’t powerful enough to reveal the Milky Way in the Bronx sky. But they did let him make out the craters on the moon. That was enough to convince him that the sky was worth looking at.

He began to work his way up through a series of telescopes. For his twelfth birthday, he got a 2.4-inch refractor with three eyepieces and a solar projection screen. Dog walking earned him a five-foot-long Newtonian with an electric clock for tracking stars. Tyson would run an extension cord across the Skyview’s two-acre roof into a friend’s apartment window. Fairly often, someone would call the police. He charmed the cops with the rings of Saturn.

Tyson took classes at the Hayden Planetarium and then began to travel to darker places to look more closely at the heavens. In 1973, at age fourteen, he went to the Mojave Desert for an astronomy summer camp. Comet Kahoutek had appeared earlier in the year, and Tyson spent much of his time in the Mojave taking pictures of its long-tailed entry into the solar system. After a month he emerged from the desert, an astronomer to the bone.” (Thanks Longform.)

••••••••••

“Comet Kahoutek is on its way” (at 6:30):

Tags: Carl Zimmer, Neil deGrasse Tyson

From a post on Mashable by Zachary Sniderman, about Apple’s first attempt at a game-changing phone, in 1983, even before the introduction of the Macintosh:

“The first iPhone was actually dreamed up in 1983. Forget that silly old touchscreen, this iPhone was a landline with full, all-white handset and a built-in screen controlled with a stylus.

The phone was designed for Apple by Hartmut Esslinger, an influential designer who helped make the Apple IIc computer (Apple’s first “portable” computer) and later founded Frogdesign. The 1983 iPhone certainly fits in with Esslinger’s other designs for Apple. It also foreshadows the touchscreens of both the iPhone and iPad.”

••••••••••

Esslinger, 2009:

From “The Accidental Universe: Science’s Crisis of Faith,” a Harper’s piece by physicist and novelist Alan Lightman:

“Dramatic developments in cosmological findings and thought have led some of the world’s premier physicists to propose that our universe is only one of an enormous number of universes with wildly varying properties, and that some of the most basic features of our particular universe are indeed mere accidents—a random throw of the cosmic dice. In which case, there is no hope of ever explaining our universe’s features in terms of fundamental causes and principles.

It is perhaps impossible to say how far apart the different universes may be, or whether they exist simultaneously in time. Some may have stars and galaxies like ours. Some may not. Some may be finite in size. Some may be infinite. Physicists call the totality of universes the ‘multiverse.’ Alan Guth, a pioneer in cosmological thought, says that ‘the multiple-universe idea severely limits our hopes to understand the world from fundamental principles.’ And the philosophical ethos of science is torn from its roots. As put to me recently by Nobel Prize–winning physicist Steven Weinberg, a man as careful in his words as in his mathematical calculations, ‘We now find ourselves at a historic fork in the road we travel to understand the laws of nature. If the multiverse idea is correct, the style of fundamental physics will be radically changed.'”

••••••••••

Brian fails to complete his novel in several universes:

Tags: Alan Guth, Alan Lightman, Steven Weinberg

Max Headroom was a computer-generated talking head who existed only on television, and I suspect the same is true of Charlie Rose. From 1986:

Tags: Charlie Rose, David Letterman, Max Headroom

From “Between the Lines,” a really interesting piece in L.A. Magazine by Dave Gardetta about the science of parking spaces, a segment about UCLA traffic guru Donald Shoup:

“In the United States hundreds of engineers make careers out of studying traffic. Entire freeway systems like L.A.’s have been hardwired with sensors connecting to computer banks that aggregate vehicle flow, monitor bottlenecks, explain congestion in complicated algorithms. Yet cars spend just 5 percent of their lives in motion, and until recently there was only one individual in the country devoting his academic career to studying parking lots and street meters: Donald Shoup.

Shoup is 73 years old. He drives a 1994 Infiniti but for the last three decades has steered a 1975 Raleigh bike two miles uphill daily in fair weather, from his home near the Mormon temple to the wooded highlands of UCLA’s north campus. He was born near one shore (Long Beach), grew up on a far shore (Hawaii), and resembles a 19th-century figure sketched by Melville. He has a mildly hectic complexion, a halo of silver hair that breaks over his small ears into a white froth of a beard, and brimstone eyes. This year Shoup’s 765-page book, The High Cost of Free Parking, was rereleased to zero acclaim outside of the transportation monthlies, parking blogs, and corridor beyond his office door in UCLA’s School of Public Affairs building. He wasn’t surprised—’There’s not even a name for what I do,’ he says. Shoup, however, does not lack for acolytes. His followers call themselves Shoupistas, like Sandinistas, and on a Facebook page they leave posts suggesting parking meters for prostitutes and equations that quantify the contradiction between time spent cruising for free parking versus the ‘assumed time-value’ cited to justify expanding roadways. (The hooker stuff is more interesting.)

After 36 years, Shoup’s writings—usually found in obscure journals—can be reduced to a single question: What if the free and abundant parking drivers crave is about the worst thing for the life of cities? That sounds like a prescription for having the door slammed in your face; Shoup knows this too well. Parking makes people nuts. ‘I truly believe that when men and women think about parking, their mental capacity reverts to the reptilian cortex of the brain,’ he says. ‘How to get food, ritual display, territorial dominance—all these things are part of parking, and we’ve assigned it to the most primitive part of the brain that makes snap fight-or-flight decisions. Our mental capacities just bottom out when we talk about parking.'” (Thanks Longform.)

•••••••••

Godard‘s darkly comic 1967 traffic nightmare:

Goofy on a superhighway, 1965:

Tags: Dave Gardetta, Donald Shoup

Tags: Richard Feynman

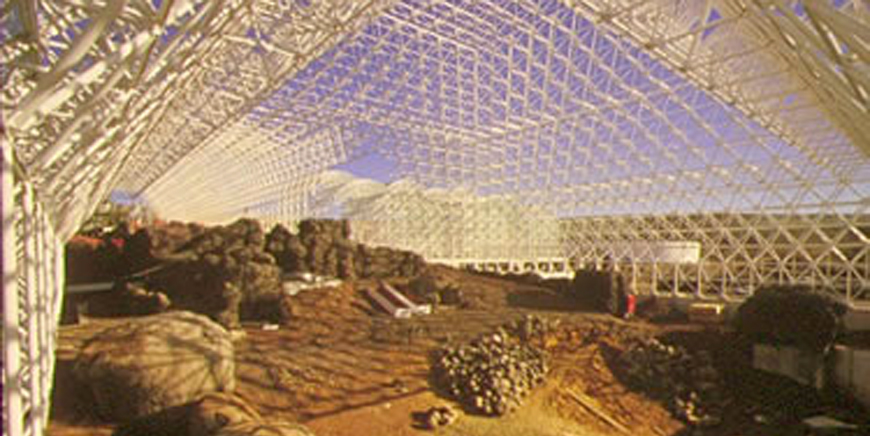

Built in the 1990s in Arizona, Biosphere 2 was a sealed and self-contained ecological world that was to house a team of researchers during two closures. But even controlled environments can’t really be controlled. Disputes over financial management led to the early termination of Biosphere 2 in 1994, and ownership of its remants have changed hands several times, as if it were a failed department store. From a 1996 New York Times article by William J. Broad about Columbia University taking over Biosphere for a spell, at a time when it lay dormant, a domicile only to exotic ants:

The exotic species of ant known as Paratrechina longicornus, or the crazy ant, named for its speedy and erratic behavior when excited, somehow managed to kill off all the other ants over the years, as well as the crickets and grasshoppers.

Swarms of them crawled over everything in sight: thick foliage, damp pathways littered with dead leaves and even a bearded ecologist in the humid rain forest of Biosphere 2, an eight-story, glass-and-steel world in the wilds of the Sonora Desert that cost $200 million to build.

“These little guys pretty much run the food web,” Dr. Tony Burgess, the ecologist, said as he tapped a dark frond, sending dozens of the ants into a frenzy. ”Until we understand the ecology, we’re reluctant to eliminate them.”

Columbia University, an icon of the Ivy League, is struggling to turn a utopian failure into a scientific triumph.

The university took over management of Biosphere 2 in January and is starting to reveal just how badly things went awry when four men, four women and 4,000 species of plants and animals were sealed inside this giant terrarium for a two-year experiment that ended in 1993.

The would-be Eden became a nightmare, its atmosphere gone sour, its sea acidic, its crops failing, and many of its species dying off. Among the survivors are crazy ants, millions of them.•

_____________________________________

Biosphere 2, before its fall:

Jane Poynter recalls living in Biosphere 2, at TED:

Tags: Jane Poynter

As the Flash Mob concept closes in on a decade of existence, its originator, Wired editor Bill Wasik, has penned an article about the intersection of group behavior, technology and violence. Wasik on the origins of the idea:

“I even called my events ‘mobs,’ as a wink to the scary connotations of a large group gathered for no good reason. But I didn’t come up with the name flash mob—that honor belongs to Sean Savage, a UC Berkeley grad student who was blogging about my events and the copycats as they happened. He added the word ‘flash’ as an analogy to a flash flood, evoking the way that these crowds (which in the original version arrived all at once and were gone in 10 minutes or less) rushed in and out like water from a sudden storm. Savage and I never met while the original mobs were still going on, but today we work just a block away from each other in San Francisco—me at Wired, him at Frog Design, where he’s an interaction designer—so we now can get together and commiserate about what’s become of our mutual creation. It had been bad enough to see the term get appropriated by Oprah to describe a ridiculous public dance party featuring the Black Eyed Peas. Now the media was stretching the term to include just about any sort of group crime. ‘It means everything and nothing now,’ Savage says morosely.

One reason the term ‘flash mob’ stuck back in 2003 was its resonance, among some sci-fi fans who read Savage’s blog, with a 1973 short story by Larry Niven called ‘Flash Crowd.’ Niven’s tale revolved around the effects of cheap teleportation technology, depicting a future California where “displacement booths” line the street like telephone booths. The story is set in motion when its protagonist, a TV journalist, inadvertently touches off a riot with one of his news reports. Thanks to teleportation, the rioting burns out of control for days, as thrill-seekers use the booths to beam in from all around to watch and loot. Reading ‘Flash Crowd’ back in 2003, I hadn’t seen much connection to my own mobs, which I intended as a joke about the slavishness of fads. I laughed off anyone who worried about these mobs getting violent. In 2011, though, it does feel like Niven got something chillingly correct. He seems especially prescient in the way he describes the interplay of curiosity, large numbers, and low-level criminality that causes his fictional riots to grow. ‘How many people would be dumb enough to come watch a riot?’ the narrator asks. ‘But that little percentage, they all came at once, from all over the United States and some other places, too. And the more there were, the bigger the crowd got, the louder it got—the better it looked to the looters … And the looters came from everywhere, too.’

That last line passed for science fiction in 1973. The not-infrequent riots that wracked American cities in the 1960s tended to be strikingly localized, with rioters taking out their aggression on the immediate neighborhood in which they lived. By contrast, Nick de Bois says that of the 165 or so people arrested so far for the looting in Enfield Town, only around 60 percent hailed from the local borough, which includes not just greater Enfield but a few surrounding towns. The other 40 percent commuted in from elsewhere, including locales as far afield as Essex and Twickenham, each a good hour’s drive away. Instead of teleportation booths replacing telephone booths—how quaint!—it turned out that those phones merely had to shrink down enough to fit into our pockets.”

••••••••

Austin Flash Mob, 2003, the year it started:

Tags: Bill Wasik, Sean Savage

Robots designed to work alongside people, from the fine folks at Kawada Industries.

Damnjan Mitic has developed the the Citroën Eggo–an electric concept car like no other. Egg-shaped with all glass doors, a motor in each wheel and solar panels on the roof, it’s a car from the future that has arrived today. (Thanks Kanikasweet.)

Mitic also designs futuristic concept luggage for Samsonite:

Tags: Damnjan Mitic

A 1964 Jacques Cousteau doc about Continental Shelf Station Two, the first manned underwater colony:

Steve Zissou tells you about his boat:

Tags: Jacques Cousteau

Genesys, 1970:

Key Frame Animation, 1971:

If you want to argue that athletes shouldn’t be using PEDs because they may suffer terrible health consequences, feel free. It’s risky business. But arguing that enhancement should not occur at all is futile. We’re all going to be enhanced in the future. It’s not a matter of if it will be done but how. In “The Case for Enhancing People” in the New Atlantis, Ronald Bailey examines pretty much every angle of the topic, including the potential inequality of our brave new world. An excerpt:

“Those who favor restricting human enhancements often argue that human equality will fall victim to differential access to enhancement technologies, resulting in conflicts between the enhanced and the unenhanced. For example, at a 2006 meeting called by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Richard Hayes, the executive director of the left-leaning Center for Genetics and Society, testified that ‘enhancement technologies would quickly be adopted by the most privileged, with the clear intent of widening the divisions that separate them and their progeny from the rest of the human species.’ Deploying such enhancement technologies would ‘deepen genetic and biological inequality among individuals,’ exacerbating ‘tendencies towards xenophobia, racism and warfare.’ Hayes concluded that allowing people to use genetic engineering for enhancement ‘could be a mistake of world-historical proportions.’

Meanwhile, some right-leaning intellectuals, such as Nigel Cameron, president of the Center for Policy on Emerging Technologies, worry that ‘one of the greatest ethical concerns about the potential uses of germline interventions to enhance normal human functions is that their availability will widen the existing inequalities between the rich and the poor.’ In sum, egalitarian opponents of enhancement want the rich and the poor to remain equally diseased, disabled, and dead.

Even proponents of genetic enhancement, such as Princeton University biologist Lee M. Silver, have argued that genetic engineering will lead to a class of people that he calls the ‘GenRich,’ who will occupy the heights of the economy while unenhanced ‘Naturals’ provide whatever grunt labor the future economy needs. In Remaking Eden (1997), Silver suggests that eventually ‘the GenRich class and the Natural class will become … entirely separate species with no ability to cross-breed, and with as much romantic interest in each other as a current human would have for a chimpanzee.’

In the same vein, George J. Annas, Lori B. Andrews, and Rosario M. Isasi have laid out a rather apocalyptic scenario in the American Journal of Law and Medicine:

The new species, or ‘posthuman,’ will likely view the old ‘normal’ humans as inferior, even savages, and fit for slavery or slaughter. The normals, on the other hand, may see the posthumans as a threat and if they can, may engage in a preemptive strike by killing the posthumans before they themselves are killed or enslaved by them. It is ultimately this predictable potential for genocide that makes species-altering experiments potential weapons of mass destruction, and makes the unaccountable genetic engineer a potential bioterrorist.

Let’s take their over-the-top scenario down a notch or two. The enhancements that are likely to be available in the relatively near term to people now living will be pharmacological — pills and shots to increase strength, lighten moods, and improve memory. Consequently, such interventions could be distributed to nearly everyone who wanted them. Later in this century, when safe genetic engineering becomes possible, it will likely be deployed gradually and will enable parents to give their children beneficial genes for improved health and intelligence that other children already get naturally. Thus, safe genetic engineering in the long run is more likely to ameliorate than to exacerbate human inequality.” (Thanks Browser.)

Tags: Ronald Bailey

The opening of “The Xinjiang Procedure,” Ethan Gutmann’s alarming Weekly Standard article about the organ market that surrounds executions of China’s political prisoners:

“To figure out what is taking place today in a closed society such as northwest China, sometimes you have to go back a decade, sometimes more.

One clue might be found on a hilltop near southern Guangzhou, on a partly cloudy autumn day in 1991. A small medical team and a young doctor starting a practice in internal medicine had driven up from Sun Yat-sen Medical University in a van modified for surgery. Pulling in on bulldozed earth, they found a small fleet of similar vehicles—clean, white, with smoked glass windows and prominent red crosses on the side. The police had ordered the medical team to stay inside for their safety. Indeed, the view from the side window of lines of ditches—some filled in, others freshly dug—suggested that the hilltop had served as a killing ground for years.

Thirty-six scheduled executions would translate into 72 kidneys and corneas divided among the regional hospitals. Every van contained surgeons who could work fast: 15-30 minutes to extract. Drive back to the hospital. Transplant within six hours. Nothing fancy or experimental; execution would probably ruin the heart.” (Thanks Longform.)

••••••••••

“Patients are suspended by wires through long bones”:

Tags: Ethan Gutmann

The opening of “The Real Cape Kennedy Is Inside Your Head,” a Dylan Trigg meditation in 3:AM Magazine about J.G. Ballard’s “Cape Canaveral” stories:

Against a saturated blue sky, a landscape is in a state of decomposition. Semi-gelatinous material entwines with desiccated chunks of a destroyed world. Towering shafts of ruined debris shoot haphazardly into the sky, forming a monolithic domelike structure in the process. A cow—or its head—appears trapped in the rubble, its body colonised by the ruins. Into this zone of mutilation, two figures, a man and a woman, stand adrift. They enter the field of our horizon and then remain motionless in the ruins. The woman is dressed elegantly, her back turned to the viewer, her body in motion. Turning toward her, a man with the skull of a bird looks on passively. Whether or not they were caught in the destruction or have returned to survey the remains, the viewer cannot be sure. In each case, they are no longer recognisable as “human” and instead have begun assuming the physiognomic characteristics of the landscape. Like the cow, their bodies are in a state of atrophy, their tones now mirroring the colouring of the landscape. Everywhere, borders collapse. What looks like the remains of a civilization may also be the inception of a new world. Similarly, if there are humans in the ruins, then they might just as easily be a new species of life, composed from both the organic and synthetic waste left behind. In the rot and the ruin, there is also life and vitality, a bewildering fusion of different orders of space and time colliding in the same sphere.

We are in the world of Max Ernst’s celebrated painting, Europe After the Rain II. Painted between 1940-1942, the work has become canonised as a masterpiece in the surrealist tradition. For J.G. Ballard, the landscapes of Max Ernst assumed a particular importance in his own thinking and writing. Above all else, what Ballard was able to discover in Ernst’s visions was a symbiosis of the natural and the supernatural, the banal and the uncanny, all of which begin not in the objective features of the landscape, but in the pathology of inner space. In his words, Ernst’s world took the form of “self-devouring phantasmagoric jungles [which] screamed silently to itself, like the sump of some insane unconscious.” Like the German romantics who influenced him, Ernst’s eerie forests and organic cities are emblems of the inner working of the deep unconscious manifest—as though by accident—on the canvas of the work. In Ballard, the same process of alchemically distilling disjoined images from the prima materia of everyday life finds its strange expression in his repetition of motifs. Abandoned parking lots, empty swimming pools, and neon nightclubs glowing in the thick forests of night all assume a level of spectral significance made possible thanks to the conjunction of inner and outer space.

Nowhere is this strange union between inner and outer space clearer than in Ballard’s “Cape Canaveral” stories, which are scattered through his writing from the early 1960s to the 1990s. In these stories, Ballard plays with themes of spatio-temporal distortion resulting from the flight into cosmic space. At once a warning against cosmic misadventures, the stories can also be read as an affirmation of humanity’s transformation the misadventures entail, as he states:

By leaving his planet and setting off into outer space man had committed an evolutionary crime, a breach of the rules governing his tenancy of the universe, and of the laws of time and space. Perhaps the right to travel through space belonged to another order of beings, but his crime was being punished just as surely as would be any attempt to ignore the laws of gravity.•

Tags: Dylan Trigg, J.G. Ballard

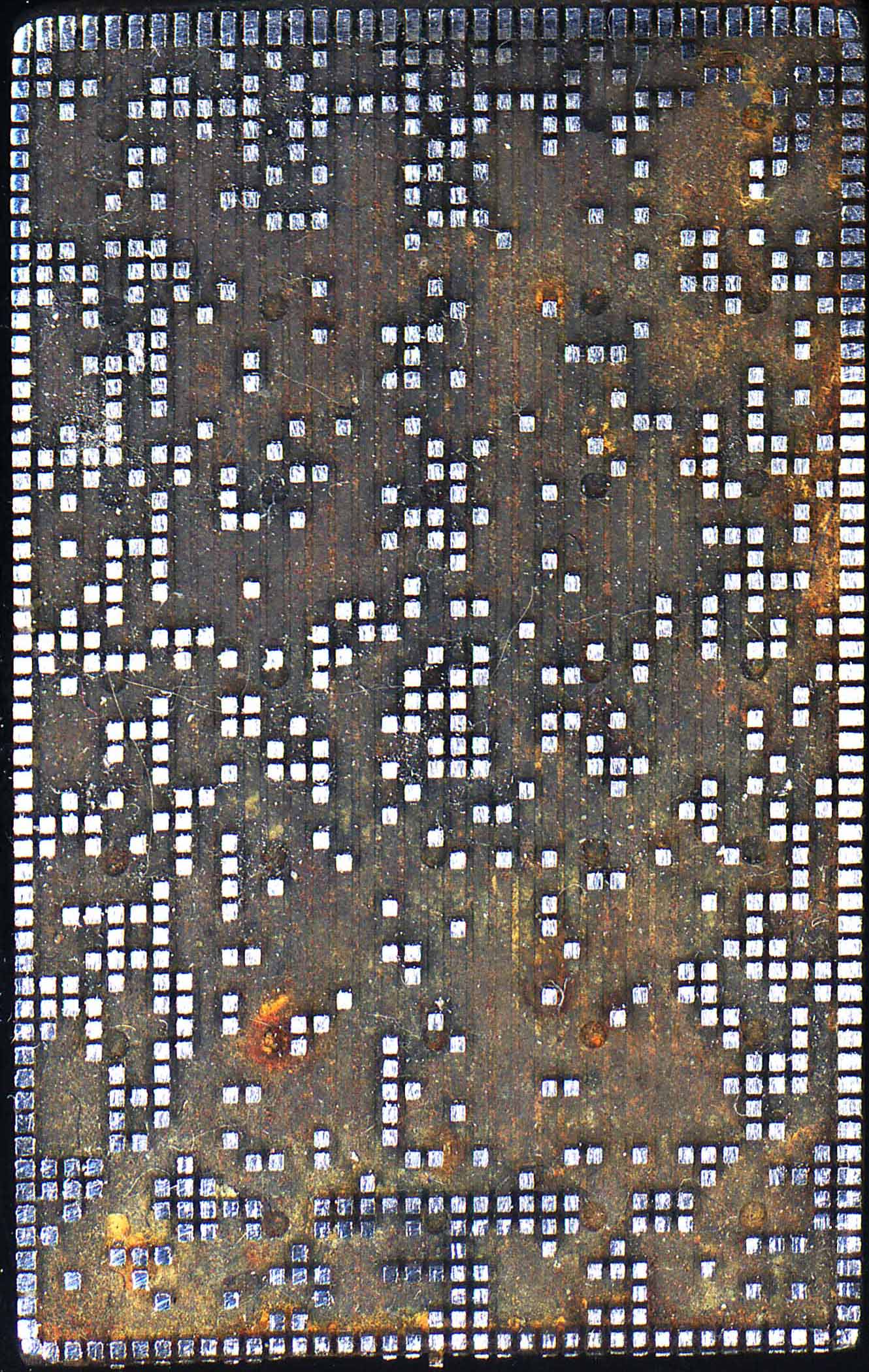

"The evolving role of digital storage in facilitating truly pervasive surveillance is less widely recognized." (Image by Bob Blaylock.)

The opening of John Villasenor’s new cautionary article, “Recording Everything: Digital Storage as an Enabler of Authoritarian Governments“:

“Within the next few years an important threshold will be crossed: For the first time ever, it will become technologically and financially feasible for authoritarian governments to record nearly everything that is said or done within their borders – every phone conversation, electronic message, social media interaction, the movements of nearly every person and vehicle, and video from every street corner. Governments with a history of using all of the tools at their disposal to track and monitor their citizens will undoubtedly make full use of this capability once it becomes available.

The Arab Spring of 2011, which saw regimes toppled by protesters organized via Twitter and Facebook, was heralded in much of the world as signifying a new era in which information technology alters the balance of power in favor of the repressed. However, within the world’s many remaining authoritarian regimes it was undoubtedly viewed very differently. For those governments, the Arab Spring likely underscored the perils of failing to exercise sufficient control of digital communications and highlighted the need to redouble their efforts to increase the monitoring of their citizenry.

Technology trends are making such monitoring easier to perform. While the domestic surveillance programs of countries including Syria, Iran, China, Burma, and Libya under Gadhafi have been extensively reported, the evolving role of digital storage in facilitating truly pervasive surveillance is less widely recognized. Plummeting digital storage costs will soon make it possible for authoritarian regimes to not only monitor known dissidents, but to also store the complete set of digital data associated with everyone within their borders. These enormous databases of captured information will create what amounts to a surveillance time machine, enabling state security services to retroactively eavesdrop on people in the months and years before they were designated as surveillance targets. This will fundamentally change the dynamics of dissent, insurgency and revolution.”

••••••••••

“Soon the ultimate tool will become the ultimate weapon”:

Tags: John Villasenor

Two short films Ray and Charles Eames made for IBM during the 1950s:

“A Communications Primer,” 1953.

“The Information Machine,” 1956.

See also:

Tags: Charles Eames, Ray Eames

Early global television broadcast, 1967, which features media seer Marshall McLuhan as a guest. “It’s a real humming, buzzing confusion,” he says, referring to the crowded control room, but also predicting the nature of the more connected, interactive media to come.

Tags: Marshall McLuhan

Mary Roach has never met a dead man she didn’t like, so it’s no surprise Outside sent her to investigate a true-life tale of head shrinking. An excerpt:

“Thirteen inches from heel to crown, the specimen is mounted on a mahogany stand that could serve as a paper-towel holder. The first thing you notice is the skin color. The Shuar believed that killing a man created an avenging soul that would leave the corpse via the mouth and come after the perpetrator. Lips were sewn shut to prevent this, and true ceremonial tsantsas have blackened skin, the result of the killer having rubbed it with charcoal to prevent the victim’s spirit from ‘seeing’ out. This child’s skin is the buff color and rough texture of a dried kalamata fig. Based on its proportions—the plump bowed legs, the nubbin of a penis, the fat cheeks—it looks more like a mummified infant than a shrunken boy. In fact, the inventory lists it as ‘stillborn.’

‘Gustav told us it had been given to him by the Shuar and that he carried it out when he escaped,’ Brown says. ‘He never told us that he himself shrunk humans.’

Brown has his laptop open and has been clicking through images from his family’s photo albums. He shows me a 1955 shot of Gus and Gert—as American friends sometimes called them—seated at a restaurant table for a family dinner in Los Angeles. Bowls and spoons are set before them. Struve looks at the camera with the mild peevishness of an old guy who wants to have his soup. He wears dress suspenders over a short-sleeved button-down shirt and sports the pencil-thin mustache he wore most of his adult life. I remark to Brown that it’s hard to picture this natty gentleman flaying bodies and boiling skins.

‘Check the pattern on the shirt,’ he says. I lean in closer. The shirt is decorated with a row of tsantsas, life-size and garish, with lips sewn shut and flowing Wonder Woman hair.

‘So he was a bit of an odd one,’ I say.

‘Well, bear in mind,’ Brown says quickly, ‘America was in the midst of a shrunken-head craze.’ He calls up a 1960s TV ad for a toy Witch Dr. Head Shrinkers Kit (‘Shrunken heads for all occasions!’) featuring a pith-helmeted actor hacking his way through what looks like a Kansas wheat field.”

••••••••••

Witch Dr. Head Shrinkers Kit ad:

Tags: Mary Roach

From “Computational Periodics,” a 1975 essay by the Pasadena-born computer-animation pioneer John Whitney:

“Also from the point of view that this Century is but an episode in the life of human culture, it is clear that more paraphernalia of this epoch may be castoff than will survive into the next. Yet surely the computer will not. A solid state image storage system will replace the silver chemical ribbon and cinema will eventually be interred in the archival museum. But computer and computer graphics bring to mind the kind of tools that may characterize an age succeeding this century’s age of the machine.”

••••••••••

“Catalog” (1961):

“Per•mu•ta•tion” (1966):

“Arabesque” (1975):

Tags: John Whitney

Sheila Nirenberg gives a TED Talk about the cutting edge of ocular prosthetics.

Tags: Sheila Nirenberg

Before he was crushed beneath the wheel of his dreams. John Z. DeLorean had as much ambition as anyone in the history of American commerce. From a 1980 People article by Martha Smilgis about the automaker, when all roads still seemed wide open and endless:

“Six years ago John Z. (for Zachary) DeLorean was earning $650,000 a year as a General Motors vice-president—with a passably clear track to the presidency—when he stunned Detroit by abruptly quitting. Two months ago he rocked Motor City again, this time because of a book that attacks his old company for waste, corruption, neglect of consumers and corporate amorality. Among some cringing auto company men, the book has made him a hero—’He’s the only man who ever fired General Motors,’ as one admirer puts it. Now DeLorean, who will be 55 this week, is about to go that one better. Next fall he will market a new sports car of his own design and production, and he has convinced some GM dealers to distribute it. ‘Don’t people believe you can start a business these days?’ DeLorean asks skeptics. ‘I’d like to show that a bunch of little guys can make it.’

The humility is attractive but a bit disingenuous. DeLorean Motor Company is a $200 million operation backed by a consortium of investors in the U.S. and Europe (Johnny Carson among them). DeLorean himself is hardly the average internal-combustion tinkerer. A twice-divorced bon vivant whose romantic life has been as prodigious as his business career, DeLorean fled Detroit in part, he says, because he was bored with it.

The disenchantment is plain in his book, On a Clear Day You Can See General Motors. Written by the former Detroit bureau chief of Business Week, J. Patrick Wright, and billed as DeLorean’s ‘own story,’ the book charges GM with official nonchalance toward the Corvair (a car that inspired Ralph Nader’s Unsafe at Any Speed). It ridicules numbing, time-wasting rituals of paper-shuffling in the executive suites and waxes outraged at the perks demanded by top GM brass. (To provide a traveling sales executive with his customary midnight snack, the book charges, GM took out a window in his hotel suite and lowered in a fully stocked refrigerator by crane.) After giving Wright all his ammunition, DeLorean pulled out of their publishing agreement—thereby saving his skin with GM—but Wright published the book anyway. ‘It came out a lot tougher than was my intention,’ DeLorean says. ‘I wanted it to be constructive.’ Then he smiles and adds, ‘GM hasn’t retaliated. In fact they’ve offered me an opportunity to merge with their Iranian subsidiary.’ A Ford factory worker’s son who paid his own way through college and earned master’s degrees in automotive engineering and business at night, DeLorean insists he has goodwill toward his old company: ‘GM was very good to me. I was an unsophisticated transmission engineer who was given many opportunities.’

What GM never appreciated, he says, was his life-style. Six-foot-four with movie star good looks, DeLorean is a physical fitness zealot who works out three times a week and is as proud of his 30-inch waist as of his latest marketing coup. Between his three marriages, he squired the likes of Ursula Andress, Joey Heatherton, Candice Bergen and Nancy Sinatra. Such glamorous escorts, along with his modishly long hair and turtleneck sweaters, scandalized automotive society. In 1973 he married fashion model Cristina Ferrare—she had lived with him for three months before saying, ‘Either we marry or I am leaving.’ The clatter of tongues grew louder. He was 48, she was 23. ‘I consider myself young for my age, so that wasn’t a problem for us,” he says. ‘But Cristina wasn’t accepted into Detroit society, and I didn’t want to subject her to that kind of vindictiveness. When I told her I wanted to leave, she supported me 100 percent.'”

••••••••••

A year before the People article was published, Gary Numan showed appreciation for automobiles:

More DeLorean posts:

Tags: J. Patrick Wright, John DeLorean, Martha Smilgis, Ralph Nader

A 1972 film about Arpanet, the Internet precursor. An amazing document.

Fab 5 Freddy, who once told me everybody’s fly, talks electronic mail, 1994:

Tags: Fab 5 Freddy