In 1974, Arthur C. Clarke described what technology would be like in 2001.

You are currently browsing the archive for the Science/Tech category.

Tags: Arthur C. Clarke

From “The Strongest Man in the World,” Burkhard Bilger’s ungated New Yorker piece about Brian Shaw, a Colorado man born to move mountains, and the new wave of strength competitions:

“In the summer of 2005, when Shaw was twenty-three, he went to Las Vegas for a strength-and-conditioning convention. He was feeling a little adrift. He had a degree in wellness management from Black Hills State University, in South Dakota, and was due to start a master’s program at Arizona State that fall. But after moving to Tempe, a few weeks earlier, and working out with the football team, he was beginning to have second thoughts. ‘This was a big Division I, Pac-10 school, but I was a little surprised, to be honest,’ he told me. ‘I was so much stronger than all of them.’ One day at the convention, Shaw came upon a booth run by Sorinex, a company that has designed weight-lifting systems for the Denver Broncos and other football programs. The founder, Richard Sorin, liked to collect equipment used by old-time strongmen and had set out a few items for passersby to try. There were some kettle bells lying around, like cannonballs with handles attached, and a clumsy-looking thing called a Thomas Inch dumbbell.

Inch was an early-twentieth-century British strongman famous for his grip. His dumbbell, made of cast iron, weighed a hundred and seventy-two pounds and had a handle as thick as a tin can, difficult to grasp. In his stage shows, Inch would offer a prize of more than twenty thousand dollars in today’s currency to anyone who could lift the dumbbell off the floor with one hand. For more than fifty years, no one but Inch managed it, and only a few dozen have done so in the half century since. ‘A thousand people will try to lift it in a weekend, and a thousand won’t lift it,’ Sorin told me. ‘A lot of strong people have left with their tails between their legs.’ It came as something of a shock, therefore, to see Shaw reach over and pick up the dumbbell as if it were a paperweight. ‘He was just standing there with a blank look on his face,’ Sorin said. ‘It was, like, What’s so very hard about this?’

When Shaw set down the dumbbell and walked away, Sorin ran over to find him in the crowd. ‘His eyes were huge,’ Shaw recalls. ‘He said, ‘Can you do that again?’ And I said, ‘Of course I can.’ So he took a picture and sent it to me afterward.’ Sorin went on to tell Shaw about the modern strongman circuit—an extreme sport, based on the kinds of feat performed by men like Inch, which had a growing following worldwide. ‘He said that my kind of strength was unbelievable. It was a one in a million. If I didn’t do something with my abilities, I was stupid. That was pretty cool.’

Three months later, Shaw won his first strongman event.”

•••••••••

Shaw deadlifting 1073 pounds this year with a torn biceps:

Tags: Brian Shaw, Burkhard Bilger

My little brother, that provocateur Steven Boone, summing up the loud, jarring, cynical last decade of multiplex fare in a recent article at Capital New York:

“The video game industry is currently in a war that the movie industry fought and decided last decade. It’s a struggle between loud, assaultive, photorealistic game design that rewards wispy attention spans while demanding minimal problem-solving skills of its players and … games where shotguns to the face and chainsaws to the jugular are not so essential.

The American film industry settled on high-resolution ultraviolence as the default multiplex experience sometime after 9/11 and sometime before its superheroic screen response, The Dark Knight. The violence is not necessarily a matter of content but of the graceless way shots jam up against one another now, keeping us invested through a constant state of agitation where narrative suspense used to do the trick.

During that decade, many viewers retreated from mainstream blockbuster cinema into the bosom of what critics call a television renaissance. So many smart, adult, spellbinding, hilarious TV shows, the story goes. Any stragglers still hoping for an immersive experience at the multiplex were suckers and masochists.”

•••••••••

From “Fuck You Productions”:

Tags: Steven Boone

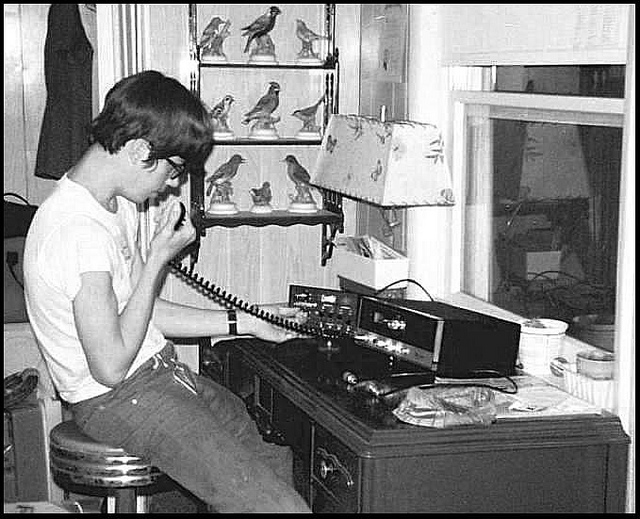

Before the Internet and social networks, people had just as great a desire to be connected, but the proper medium and infrastructure didn’t exist. For a couple of years in the 1970s, people reached out to one another via CB radio, though almost all of them hid behind a handle. They hadn’t yet perfected our brand of ego and exhibitionism. Footage from 1977.

China is on pace to become by far the world’s largest auto consumer in the near term. Sure, an economic collapse could slow that growth, but it will certainly be a world leader in the category. A nation with that much consumption, that much control over its citizenry and a huge sense of its own destiny, could decide the future of transportation and alternative energy. What if China announced it was allowing only electric cars by a certain date and then built the infrastructure to support that shift with the same zeal that it shows in routinely scraping the sky? From the Next Big Future:

“Auto sales in China may rise to 19.2 million this year, about 1 million lower than AlixPartners estimated last year. Sales in the world’s most populous country may increase to 21.4 million in 2013 and 23.5 million in 2014, the report said.

It is estimated that China’s automobile market will keep a stable growth from 2012 to 2015, with a compound annual growth rate of 8.1%. The sales volume is expected to reach 25.287 million by 2015.

China could double US car sales in 2017 / 2018 and be equal the combined car sales in Western Europe and the United States.”

••••••••••

Jack Nicholson goes gasless in 1978:

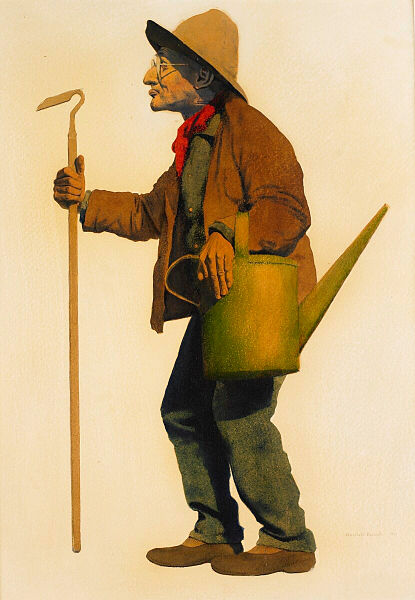

From “The Machine and the Garden,” a smart New York Times Op-Ed piece by Eric Liu and Nick Hanauer which suggests that the language we use to explain the economy is all wrong:

“Call it the ‘Machinebrain’ picture of the world: markets are perfectly efficient, humans perfectly rational, incentives perfectly clear and outcomes perfectly appropriate. From this a series of other truths necessarily follows: regulation and taxes are inherently regrettable because they impede the machine’s optimal workings. Government fiscal stimulus is wasteful. The rich by definition deserve to be so and the poor as well.

This self-enclosed metaphor is the gospel of market fundamentalists. But there is simply no evidence for it. Empirically, trickle-down economics has failed. Tax cuts for the rich have never once yielded more net revenue for the country. The 2008 crash and the Great Recession prove irrefutably how inefficient and irrational markets truly are.

What we require now is a new framework for thinking and talking about the economy, grounded in modern understandings of how things actually work. Economies, as social scientists now understand, aren’t simple, linear and predictable, but complex, nonlinear and ecosystemic. An economy isn’t a machine; it’s a garden. It can be fruitful if well tended, but will be overrun by noxious weeds if not.

In this new framework, which we call Gardenbrain, markets are not perfectly efficient but can be effective if well managed. Where Machinebrain posits that it’s every man for himself, Gardenbrain recognizes that we’re all better off when we’re all better off. Where Machinebrain treats radical inequality as purely the predictable result of unequally distributed talent and work ethic, Gardenbrain reveals it as equally the self-reinforcing and compounding result of unequally distributed opportunity.

Gardenbrain challenges many of today’s most conventional policy ideas.”

Tags: Eric Liu, Nick Hanauer

I read somewhere recently that if all of contemporary America had the population density of Brooklyn, we would be able to fit everyone into New Hampshire. The rest of the country would grow wild and beautiful while New Hampshire would stink like a graveyard restroom. King C. Gillette, razor magnate and Utopian socialist, encouraged the design of something similar in the 1890s: a hyper-concentrated metropolis made of porcelain buildings. Never quite happened. From “Impossible Cities,” by Darran Anderson at 3:AM:

“The inventor of the safety razor, business magnate and socialist, King Camp Gillette had similarly ambitious plans, writing The Human Drift in which he urged a single vast city to be built on top of the Niagara Falls (powered naturally by hydro-electricity) to house the entire population of the United States of America. It would measure 135 miles by 45 and consist of cylindrical skyscrapers made from porcelain. Pre-empting Fritz Lang’s Expressionist dystopia by decades, its name would be Metropolis.”

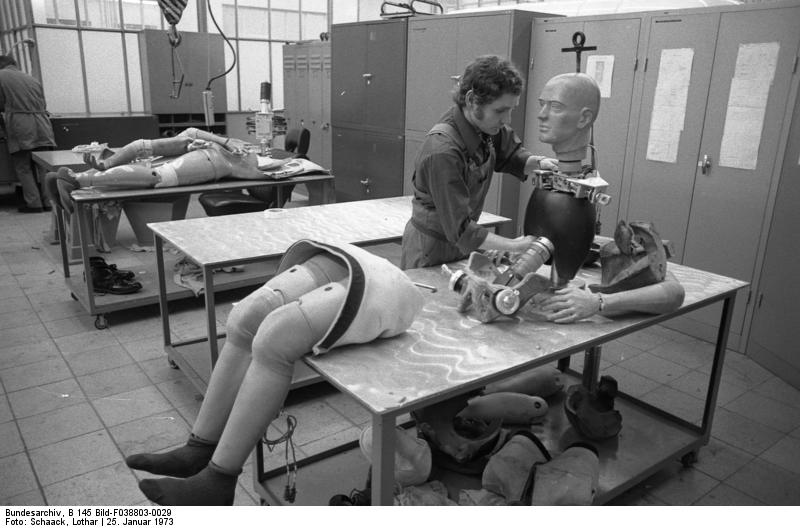

Some footage of bio-engineering research at the University of Utah in 1977, when it seemed like synthetics were the best bet for replacement organs and limbs. While better artificial extremities are now being manufactured all the time, the future looks brightest for carbon-based solutions, via computer-aided transplantation in the short run and 3-D printers a little further down the road.

The ExoHand by Festo is a robot hand that’s worn like a glove. From David J. Hill at Singularity Hub: “It may be time to jettison the notion that robots in the future will have grippers or claws for hands. The German robotics company Festo recently unveiled the ExoHand, a sophisticated robotic hand that is capable of the fine motor skills that allows the human hand to have a delicate touch or perform complex manipulations.

The ExoHand comes in two forms: as the extremity of a robotic arm or a wearable exoskeleton glove. The system is designed so that the glove can aid assembly line workers performing repetitive tasks with their hands or be used for the remote manipulation of the robotic arm by a user wearing the glove.”

Tags: David J. Hill

The swarm behavior of ants can be instructive to humans, but what about the design sense of termites? Can it aid roboticists? Will we live to see the day when millions of tiny bots build a structure from foundation to roof? A Reuters report about Harvard research on the topic.

These classic 1901 photographs show the Budapest offices of Telefon Hirmondo (or Telephone Herald), a newspaper service read via telephone to subscribers all over that city. Begun in 1893 by Transylvanian inventor Theodore Puskas–who died just a month after the service was launched–the Herald featured updated news all day and live music at night. It cost about two cents a day at the outset. At its height, the company had more than 15,000 subscribers and licensed similar setups in Italy and America. Local department stores, hotels and restaurants purchased several lines so that their customers could be hooked into flowing news and entertainment almost a century before Wi-Fi. The popularity of radio in the 1920s, however, made the telephone newspaper superfluous.

From an article about the U.S. iteration (in Newark, New Jersey) in the March 30, 1912 edition of Telephony:

While all the rest of the nation had to stop work and hang around the newspaper bulletin boards waiting in an agony of suspense for news from the Polo Grounds, in New York, last October, for half an hour, or perhaps thirty-three minutes, after the epoch-making innings there were ended, a privileged few in Newark, N. J., were able, while sitting in their own homes, to follow instantaneously, play by play, the demonstration of the fact that the Giants were next to the best baseball experts. These Newark folk who received news more promptly than that commodity had ever before been served in America were the first subscribers to the Telephone Herald, a newspaper which is independent of the Typographical Union and the Allied Printing Trades Council, for it is published over wires instead of upon paper. In other words, the subscriber does not read the Telephone Herald, but merely listens to it. He may listen to as much or as little of it as he likes; but whether he listens or not the Herald grinds on in one continuous edition from 8 o’clock in the morning until 10:30 o’clock in the evening. Its news is constantly on tap, like water or gas, for the small sum of $18 a year, or five cents a day. Additional news taps in one house are installed for $7 a year, or two cents a day. The Telephone Herald gets out a Sunday paper seven days a week with all the usual ‘magazine’ features, fiction, fashions, children’s stories and all the rest of it. Its one redeeming feature is that it has no comic supplement, thank Heaven!

In the evening the Herald ceases to be a newspaper and becomes an entertainer, furnishing a varied programme of instrumental music, songs, recitals, lectures or anything else that can be transmitted by wire.

While the telephone newspaper is a novelty on this side of the Atlantic one has been published regularly for eighteen years at Budapest, Hungary, under the name of Telefon Hirmondo.•

The schedule for the Newark version:

- 8:00: Exact astronomical time.

- 8:00-9:00: Weather, late telegrams, London exchange quotations; chief items of interest from the morning papers.

- 9:00-9:45: Special sales at the various stores; social programs for the day.

- 9:45-10:00: Local personals and small items.

- 10:00-11:30: New York Stock Exchange quotations and market letter.

- 11:30-12:00: New York miscellaneous items.

- Noon: Exact astronomical time.

- 12:00-12:30: Latest general news;naval, military and congressional notes.

- 12:30-1:00: Midday New York Stock Exchange quotations.

- 1:00-2:00: Repetition of the half day’s most interesting news.

- 2:00-2:15: Foreign cable dispatches.

- 2:15-2:30: Trenton and Washington items.

- 2:30-2:45: Fashion notes and household hints.

- 2:45-3:15: Sporting news; theatrical news.

- 3:15-3:30: New York Stock Exchange closing quotations.

- 3:30-5:00: Music, readings, lectures.

- 5:00-6:00: Stories and talks for the children.

- 8:00-10:30: Vaudeville, concert, opera.

Mechanical engineer Chris Gerdes at TED discussing robotic, driverless race cars. The human element will be lost.

Tags: Chris Gerdes

The death penalty is incredibly unevenly distributed based on race, financial standing and gender. Some innocent people are put to death because the system (and the people who make up that system) are fallible. And the punitive measure hasn’t proven to reduce crime. But yet it remains a part of justice in many parts of the United States. From an article by Caspar Melville in the New Humanist, a passage with defense attorney Clive Stafford Smith about the use of DNA in convictions:

“But doesn’t DNA therefore provide a more reliable scientific tool? Sorry, but no. ‘It’s true that DNA testing is a real science, unlike hair analysis, and in laboratory settings it is very reliable,’ explains Stafford Smith. ‘But there are two big problems: first, instead of doing it in a pristine lab you are doing it in a grubby crime scene. The second, and much bigger, problem is that the people who are doing it are basically morons. Obviously I’m overstating, but not by much. People who become forensic technicians in a crime lab are just not the sharpest knives in the drawer. So if the odds of getting a false match scientifically are one in 10 million, but the odds of the nitwit in the lab mixing up the samples are one in ten, then the scientific odds are irrelevant. I can only say this – I’ve had three cases with DNA evidence presented at trial, and I know for a fact that each one had it wrong.'” (Thanks Browser.)

Tags: Caspar Melville

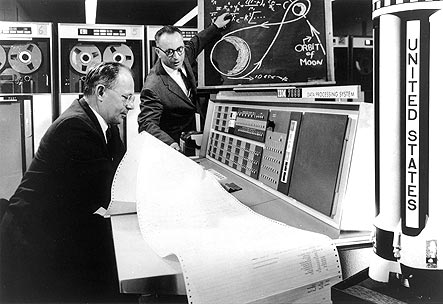

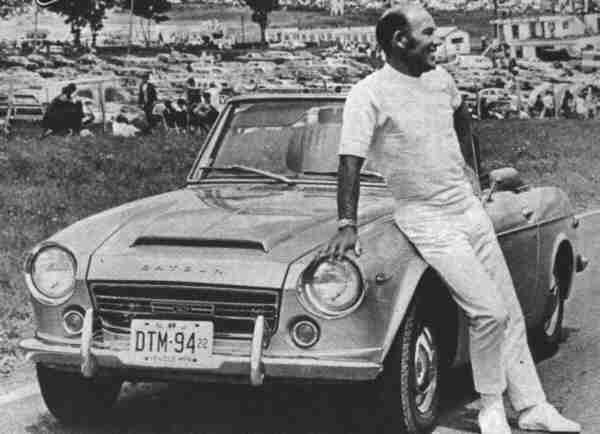

While Muhammad Ali was exiled in his own country over his refusal to perform military service in Vietnam, he “boxed” retired great Rocky Marciano in a fictional contest that was decided by a computer. Dubbed the “Super Fight,” it took place in 1970. The fighters acted out the computer prognostications and the filmed result was released in theaters. Marciano summed up this moment of Singularity the best: “I’m glad you’ve got a computer being the man that makes the decision.” A piece of the film:

Tags: Muhammad Ali, Rocky Marciano

Thinking about phone booths reminds me of this image from the end of the 1930s. (It’s a part of the Larry Zim Collection at the Smithsonian.) It is simply captioned: “Two couples in a futuristic family telephone booth at the New York World’s Fair in 1939.” Some people thought that technology was going to get bigger, more expansive, but others knew we would end up putting everything on the head of a pin.

Telephone booths, those pre-mobile totems to obsolesence, are being repurposed in NYC. From Ryan Kim at Gigaom:

“Payphones, those relics of the pre-cellphone era, may just get a new lease on life in New York. The city is testing a pilot program in which it installs free Wi-Fi on select payphone kiosks.

The hotspots are initially coming to ten payphones in three of the boroughs and will be open to the public to access for free. Users just agree to the terms, visit the city’s tourism website and then they’re up and running. Currently, there are no ads on the service, but there could be in the future.”

Tags: Ryan Kim

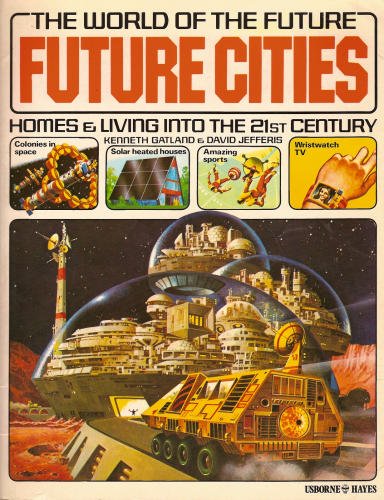

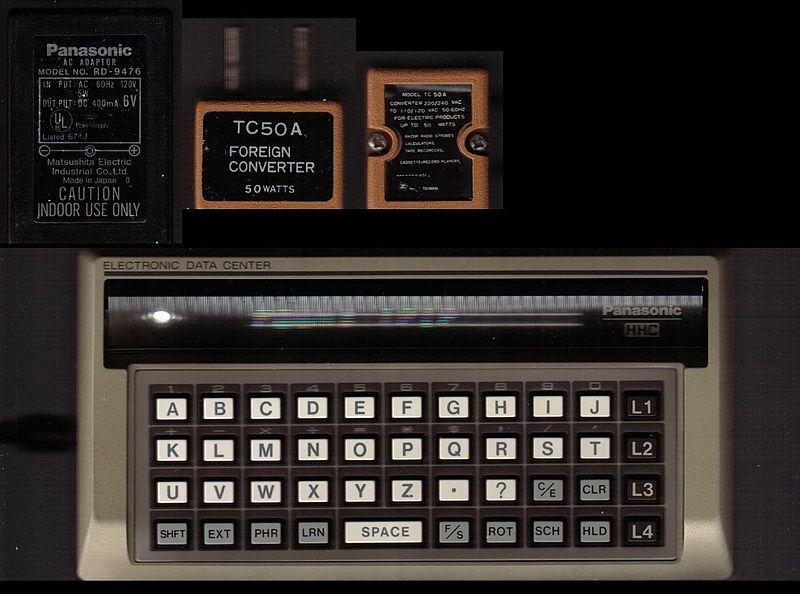

Xeni Jardin at Boing Boing put up a fun post about Future Cities: Homes and Living into the 21st Century, a 1979 children’s book by Kenneth William Gatland and David Jefferis. It envisioned a brave new world, some of which has come to pass, though not yet the domestic robot that rolls into the living room with drinks. From the section “Computers in the Home”:

“The same computer revolution which has resulted in calculators and digital watches could, through the 1980s and ’90s, revolutionize people’s living habits.

Television is changing from a box to stare at into a useful two-way tool. Electronic newspapers are already available–pushing the button on a handset lets you read ‘pages’ of news, weather puzzles and quizzes.

TV-telephones should be a practical reality by the mid 1980s. Xerox copying over the telephone already exists. Combining the two could result in millions of office workers being able to work at home if they wish. There is little need to work in a central office if a computer can store records, copiers can send information from place to place and people can talk on TV-telephones.”

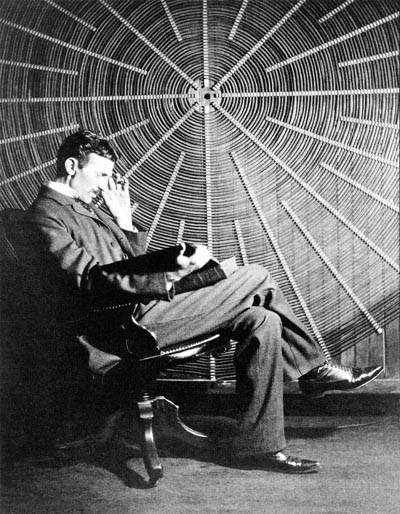

A hammer can be a tool or a weapon depending on how you swing it, but we can’t depend on implements or technology to bring about peace. In dedicating the opening of the Niagara Falls hydroelectric power plant on January 12, 1897, Nikola Tesla, who was born 156 years ago today, rightly announced the following century as one of science but didn’t foresee the horrors that such a shift would make possible. His speech:

“We have many a monument of past ages; we have the palaces and pyramids, the temples of the Greek and the cathedrals of Christendom. In them is exemplified the power of men, the greatness of nations, the love of art and religious devotion. But the monument at Niagara has something of its own, more in accord with our present thoughts and tendencies. It is a monument worthy of our scientific age, a true monument of enlightenment and of peace. It signifies the subjugation of natural forces to the service of man, the discontinuance of barbarous methods, the relieving of millions from want and suffering.”

Tags: Nikola Tesla

Tags: Slavoj Žižek

Sandy Hingston’s Philadelphia magazine article “The Psychopath Test” examines the work of Penn criminologist Adrian Raine, who believes that psychopathy may be largely a function of biology and that we may soon be able to detect such inclinations in small children. It’s hard to think of an ethically thornier topic. Raine explains how “successful psychopaths,” who share some traits with their murderous brethren, make their way in the world. An excerpt:

“Successful psychopaths, Raine’s research showed, have some of the negative brain-structure ‘hits’ of unsuccessful ones, but exhibit enhanced executive function. They don’t show significant gray matter reduction in the prefrontal cortex. Raine thinks the better frontal-lobe functioning makes them smarter, and more sensitive to environmental cues that predict danger and capture.

It may also make them ideal capitalists. The incidence of psychopathy in the business world is four times that of the general population. Psychopaths are reckless; when placing bets, they wager more the more they lose. The behavioral brakes the rest of us have are missing. ‘Individuals with psychopathic traits,’ Raine’s study of successful psychopaths states, ‘enter the mainstream workforce and enjoy profitable careers … by lying, manipulating and discrediting their co-workers.’ Closing factories and eliminating thousands of jobs requires a certain lack of empathy. So does generating sub-zero mortgages, or suggesting that a wife falsely accuse her husband of child abuse in a custody trial.

Raine isn’t arguing that any one brain malformation or genetic abnormality guarantees psychopathy—but he believes science will eventually pin down what does. What his studies show now is predisposition—the inclination toward evil. It can be reinforced by having bad parents or eating a bad diet; it can be mitigated by a positive environment and good food (but not always—plenty of psychos grow up in normal, loving homes). There are reasons for his caution. ‘We have a history of misusing research in society,’ he says, mentioning the Tuskegee Experiment.”

Tags: Sandy Hingston

From a discussion at the Browser with language scholar Nicholas Ostler, a passage about what technology and geopolitics might mean to the dominion of English and the dying of languages:

“Ostler: As things stand at the moment, the forces that have put English where it is – which mostly had to do with global economic power, first of the British Empire and then the United States – have come to the point where they are being overtaken. The crucial thing is that what put English where it is today is not going to be a feature in the future, and one has to think how the world is going to react to that. There will be other dominant powers which have non-English languages associated with them, notably the so-called BRIC countries – Brazil, Russia, India and China.

At the same time, we have a crisis in all the ‘little guys’ in the world’s languages, where we seem to be losing them at a very fast rate – something like two a month. There are a lot of languages around, perhaps 6,000 or 7,000, but if we continue to lose two a month we are going to see about half the world’s languages disappear in the course of a century. There is time for things to change. One of the things which is changing is the way we are using our languages and, in particular, their involvement with technology. One of the more significant developments in technology at the moment is machine translation and other electronic means of getting access to what’s going on in languages other than your own. These technologies are going to become more significant and are already becoming available to people who own handheld devices. If you combine that technical fact with the undying human preference for using one’s own language, you are going to see people using this technology to avoid having to resort to foreign languages such as English.”

Tags: Nicholas Ostler

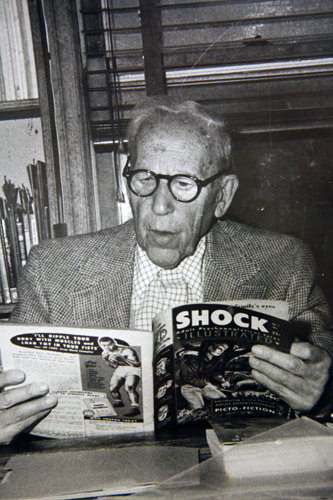

In 1968, William F. Buckley interviewed German-American psychiatrist Dr. Fredric Wertham, who had a profound effect on American culture in an assortment of ways. Dr. Wertham focused his studies on violence, and beginning in the 1940s began crusading against the comic books that were devoured freely by children. His work led to the 1950s Congressional hearings about the comics industry which nearly derailed one of the country’s most unique contributions to culture.

But Wertham had a far wider career than that. He also wrote a seminal paper about segregation that helped the Supreme Court decide Brown v. Board of Education, funded a mental health facility in Harlem for residents who had nowhere else to turn for treatment of psychological problems and was one of three physicians to interview and adjudge insane Albert Fish, the “Brooklyn Vampire,” who was one of the most notorious murderers in U.S. history.

Tags: Albert Fish, Albert H. Fish, Fredric Wertham, William F. Buckley

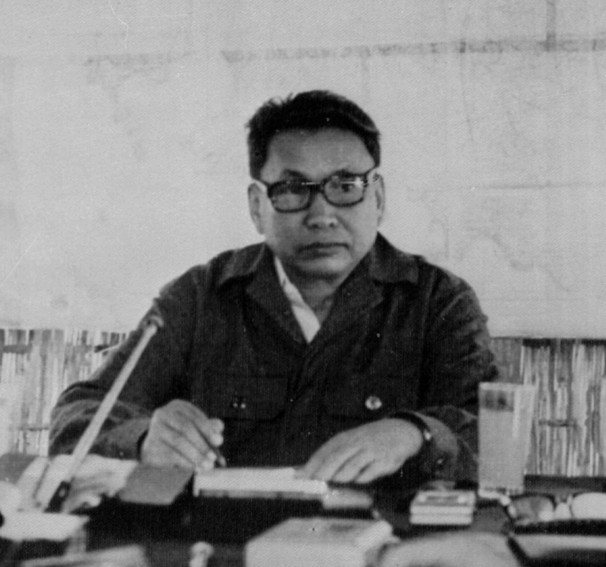

From a well-written Financial Times piece by Simon Kuper about the rise (perhaps) of the technocrat and the privatazing of progress, although I think there is a middle ground between the Pol Pot’s perverted utopianism and Bill Clinton’s tireless triangulation:

“Politicians now try to present themselves not as saviours but as managers: Romney, Mario Monti and even Hollande. That’s no wonder, as since 1945 the managerialism of Dwight Eisenhower or Bill Clinton has fared rather better than the utopianism of, say, Pol Pot. As George Orwell wrote in 1943: ‘Plans for human betterment do normally come unstuck, and the pessimist has many more opportunities of saying ‘I told you so’ than the optimist.’ In Ukraine last month, a liberal dissident mused to me about who might be the country’s ideal leader, everyone else having failed. He came up with Lee Kuan Yew or General Franco. Progress has vanished not just from politics but from public life generally: the British municipal libraries that once stood for progress are now being closed.

However, progress has merely gone private. The western middle-classes increasingly believe in progress in their own lives. They read self-help books, take cooking classes, go on diets, stop smoking, do ‘home improvement,’ and have invented a new mode of parenting, ‘concerted cultivation,’ which largely means the sort of nonstop education for your own children that those moustachioed socialists had envisioned for the workers.”

Tags: Simon Kuper

The New York Times’ David Carr, one of the nation’s very best newspaper writers, has a devastating article about the hopeless condition of newsprint in the Digital Age. It sounds more like a death knell than a clarion call. Of course, I read it online and even though I’m a complete news junkie I haven’t bought a paper in years. An excerpt:

“‘Most newspapers are in a place right now that they are going to have to make big cuts somewhere, and big seams are bound to show up at some point,’ said Rick Edmonds, a media business analyst at the Poynter Institute.

Some of the bigger cracks can’t be papered over by financial engineering. Hedge funds, which thought they had bought in at the bottom, are scrambling for exits that don’t exist. Many newspaper companies are hugely overburdened with debt from ill-timed purchases. And though it is far less discussed, newspapers are being clobbered by paltry returns on underfunded pension plans.

Two highly placed newspaper executives told me last week that while the industry had already experienced a number of strategic bankruptcies, more will most likely take place to deal with pension obligations.

As Mike Simonton of Fitch Ratings pointed out to me, very few bond investors are even willing to lend to papers. He said the pension obligations ‘represent a call on capital at a time when newspapers desperately need to deploy capital toward evolving their business models and adapting to the digital world.'”

Tags: David Carr

From Silicon Republic: “A group of researchers from University of Arizona in the US have come up with a robotic set of legs to mimic the act of walking. They’re claiming their robotic innovation is the first to fully model walking in a biologically accurate manner.

Researchers from the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at University of Arizona are behind the robotic legs. To create the legs, they studied the neural musculoskeletal architecture and sensory feedback pathways in humans, before simplifying them and weaving them into the robot to make it mirror the act of walking.”