Why do I have to wait to see Andrew Bujalski’s film Computer Chess when I want to see it right now? From Indiewire:

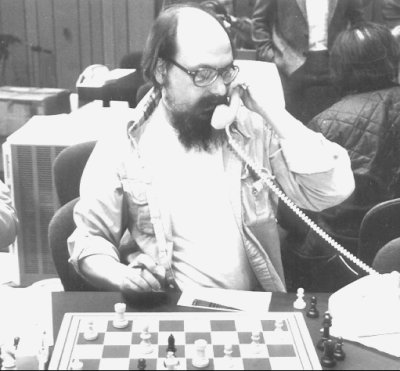

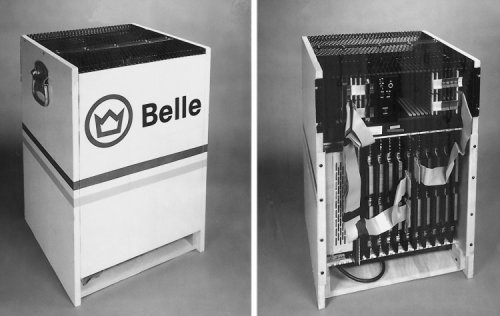

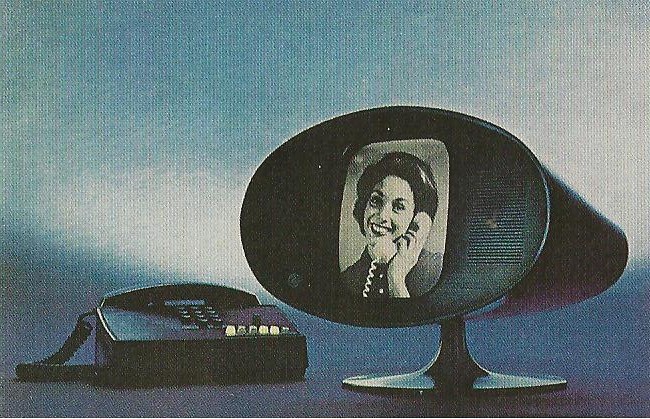

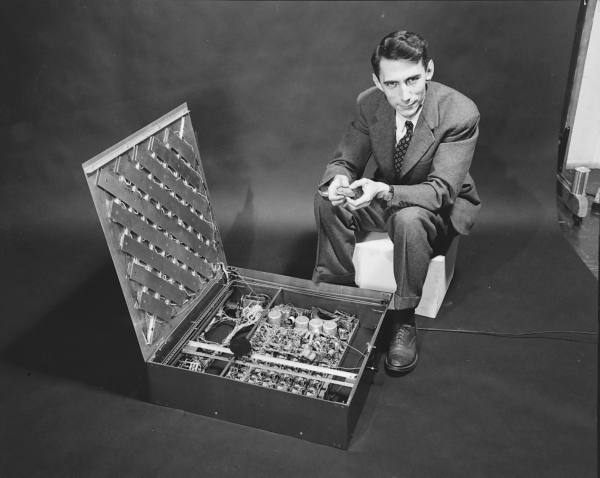

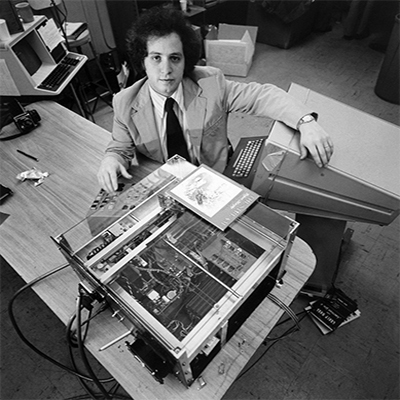

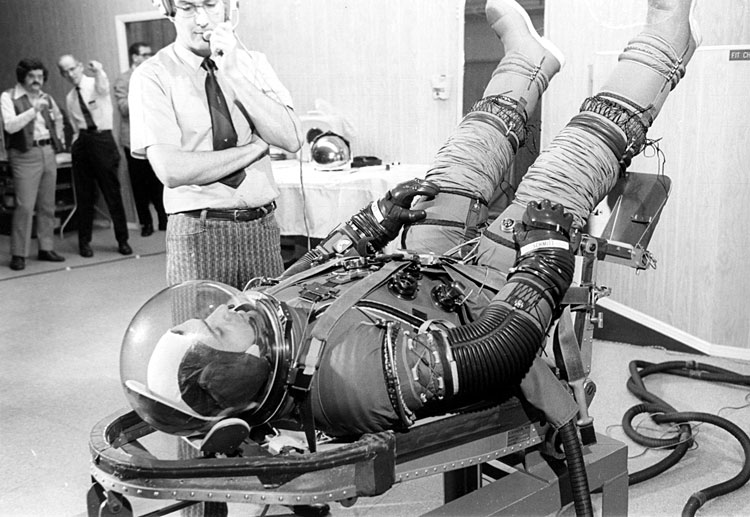

“Set around 1980, Computer Chess is the fictional account of the computer programmers and chess players that tested artificial intelligence through computer-human chess tournaments. These were the days of Bobby Fischer and Garry Kasparov, slightly before the IBM computer Deep Blue took reign.

But Bujalski’s film is not about these real-life people; it’s an exploration of the environment he imagines for these programmers. Speaking with indieWIRE, Bujalski says, ‘We’ve certainly done research, and a few people in that community have talked to us and helped us out. We’re not setting up to do a documentary or a slavish interpretation of the truth. I certainly have tremendous respect for those guys and for what they accomplished. I hope some of that will come through whether or not we get it right for them.’

Though Bujalski says he was never a computer nerd, he admits this film is a way of him exploring the geek that never was. ‘Perhaps deep down it’s my attempt to vicariously peek into the fantasy braniac life I ought to have pursued as a kid.’

Speaking with Indiewire, he elaborated on arriving to the story: ‘I was only a little kid at this time. I saw the same headlines as everyone else did about Deep Blue. I was never terribly invested in the topic in those days. The idea for the film really came when I was at the New England Mobile Book Fair — Newton Highlands, MA. They have this great remainders section. I’ve been going to that bookstore since I was a kid. There are books waiting for someone to love them, and many of them have been there for 25-30 years, if not longer. I found a book on chess trivia — it was $1 or $2. I’m not nearly enough of a chess enthusiast to buy it at full price. The book was from 1986 or so and there was a section on computer chess trivia. It started to plant images in my head, of these guys and what they were up to.'”