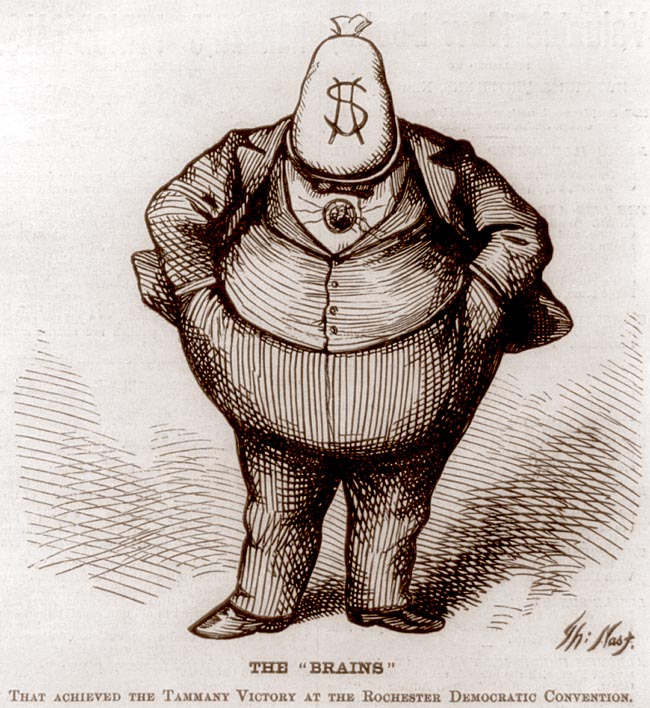

The most important thing for Apple’s future will be the first new product it produces post-Jobs that isn’t just an iteration of another one (e.g., shrinking the iPad). Even if Steve Jobs himself had the product in the pipeline, the way it’s executed and introduced will determine what Apple is going forward. But even if the company delivers, stock price won’t necessarily follow, because that isn’t always congruous with performance. The circus is still popular, but it isn’t the same without P.T. Barnum, minus his perfections and imperfections. From Bruce Nussbaum’s new Fast Company essay, “Why Apple Is Losing Its Aura“:

“Apple, of course, also gives us traditional physicality and aesthetics in the tactility of its products and the touch-screen mode of our communicating with them. For two decades or so, corporations shifted away from ‘things’ to ‘services’ and ‘thinking’ and ‘monetizing,’ but Apple stayed with making beautiful stuff that felt good in the hand. The ‘fit and finish,’ the glass and aluminum, the size and shape of its products added to the company’s Aura. Now Amazon (with its Kindle), Google (with its glasses), and others are following.

Finally, Aura is often associated with charisma. It is the charismatic figure that personifies and makes possible all the elements of Aura. It is the charismatic figure that people identify with and hope to emulate. They have high expectations for this leader but are forgiving of sins if they are acknowledged and changed. Jobs played that role, in close association with Ive and a small team of incredibly creative people who worked with him for many years.

This Aura, this combination of elements that beckon us to Apple and compel us to stay, is the generator of its economic value. This emotional engagement, not simply the number of iPhones sold worldwide, is the real value of the company. Looking at Apple’s value through the concept of aura allows us to move beyond the technology and the units sold to place the company’s economic value within a social context from which it is derived. If you don’t understand the auratic power of engagement, you can’t understand Apple or modern capitalism.” (Thanks Browser.)