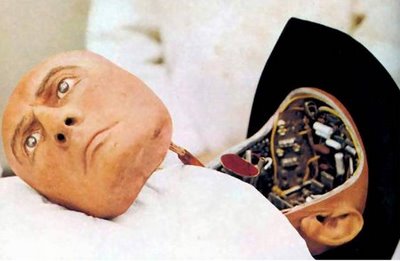

From the thoughtful people at Boston Dynamics, a new, camouflaged and more lifelike version of Petman. From the company’s copy: “PETMAN has sensors embedded in its skin that detect any chemicals leaking through the suit. The skin also maintains a micro-climate inside the clothing by sweating and regulating temperature.”

You are currently browsing the archive for the Science/Tech category.

Moving automated grading beyond multiple choice ovals and No. 2 pencils, a new software has been developed that is said to be capable of grading essays. This can’t be good. From John Markoff in the New York Times:

“Imagine taking a college exam, and, instead of handing in a blue book and getting a grade from a professor a few weeks later, clicking the ‘send’ button when you are done and receiving a grade back instantly, your essay scored by a software program.

And then, instead of being done with that exam, imagine that the system would immediately let you rewrite the test to try to improve your grade.EdX, the nonprofit enterprise founded by Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to offer courses on the Internet, has just introduced such a system and will make its automated software available free on the Web to any institution that wants to use it. The software uses artificial intelligence to grade student essays and short written answers, freeing professors for other tasks.

The new service will bring the educational consortium into a growing conflict over the role of automation in education.”

Tags: John Markoff

The new technologies allow us to learn more about ourselves (when we’re not busy using them to delude ourselves), but the they also provide this information to corporations and governments. From “The Age of Digital Improvability,” Sunil Khilnani’s Livemint piece about the double-edged sword of the “self-quant” movement:

“In the past that technocratic ambition was associated with states and government—benign know-alls who would govern in the interests of the populace. That dream has now resurfaced, in a form more attractive to a generation mistrustful of government and the state, but enamored of their own capacity to manage their well-being.

Now, the dream of continuous self-improvement can be realized by our own actions, with our own gadgets. We can all now discover our own inner technocrat—that better self, who compiles the data, creates the databanks, and then seeks to regulate our behavior to bring it into line with ‘best practice.’ Like the mirror in the gym, digital tracking becomes a perpetually at-hand guide to make us self-aware of our patterns and habits—and, as with the mirror in the gym, it also lets us steal glances at the performance of others, so we can compare and improve.

And yet. Self-quantification may be a way of making us feel unique—creating our own individual number profile. But it also turns us into a statistic, an impersonal number that can be compared with others. The accumulation of large data sets on habits and actions, the creation of ranking systems for products, services, experiences—all this gives governments and policymakers, companies and organizations, the raw material through which to shape our behavior. New policy strategies are emerging, connecting such data with behavioral psychology.”

Tags: Sunil Khilnani

There was a brief mention on the New Yorker site the other day about one of the first science stories the magazine ever published, Malcolm Ross’ 1931 article “The Invention Factory,” a Depression-era look inside Bell Labs early in the century it dominated world science. As Jon Gertner reminded in last year’s The Idea Factory, Bell Labs was rewriting the rules of communication back when talkies were the newest thing. An excerpt from the gated piece that highlights just three ways that AT&T’s research division was changing life at the time the article was published:

“The most recent achievement of the Laboratories is the improvement of airplane radiotelephony to the point where a pilot can be heard anytime that he wants to talk to groundlings. For the past year two airplanes have been flying around New Jersey, by day and by night, in the worst weather they can find, near the ground and at high altitudes. A neat pattern of efficiency under all conditions was accumulated. The equipment engineers studied it and tinkered again with their devices. Already every mail pilot over the Alleghenies has a human voice from below to direct him.

Fairly soon the teletypewriter girl may make her Wall Street debut. The machines are the same as those one hundred and twenty-two electrical typewriters now used in the New York State Police network. A message typed on one will reproduce on any, or all, of the others. The new trick is a switchboard which will connect all subscribers to the service. You will call Operator by pounding ‘OPR.’ She plugs in your correspondent and what you type on your machine comes out on his. This puts business deals in printed form, which is better confirmation than spoken words and cheaper than telegrams. If your party isn’t in his office, Operator lets you write on his typewriter and he finds your message when he gets back. …

Fairly soon the teletypewriter girl may make her Wall Street debut. The machines are the same as those one hundred and twenty-two electrical typewriters now used in the New York State Police network. A message typed on one will reproduce on any, or all, of the others. The new trick is a switchboard which will connect all subscribers to the service. You will call Operator by pounding ‘OPR.’ She plugs in your correspondent and what you type on your machine comes out on his. This puts business deals in printed form, which is better confirmation than spoken words and cheaper than telegrams. If your party isn’t in his office, Operator lets you write on his typewriter and he finds your message when he gets back. …

Hollywood, of course, relies on Bell Laboratory for its technology. Eight months ago the Laboratories turned over to Hollywood an improved sound-recording system which nearly eliminates the buzzing noise which is continually present in all talkies made under the former method. To demonstrate the improvement they made a talkie which begins with the usual blurred sound background, then suddenly clears. The difference is impressive enough to make you conscious of a distinct gratitude for the release from noisy irritation.”

Tags: Malcolm Ross

Will all your friends soon be electric? Will you? The centuries-old technique of transcranial direct-current stimulation is gaining new prominence in the science of human augmentation. From “Spark of Genius,” the new Will Oremus article at Slate:

“Exactly how all of this works is not yet fully clear. But the process appears to make neurons in the stimulated area more malleable, so that new connections form more readily while under the influence of the current. It remains to be seen whether those changes are short-lived or enduring, but at least one study has found positive effects persisting for up to six months. The beauty of it, in theory, is that the electric current doesn’t rewire the brain on its own—it just makes it easier for the brain to rewire itself.

At this point it seems obvious that this is far too good to be true. So what’s the catch?

The catch is that we don’t know what the catch is. And to Peter Reiner, a neuroscientist at University of British Columbia, that’s a biggie. If tDCS can so quickly change the brain in ways that we can easily measure, he says, there’s a good chance it could also change the brain in ways we can’t easily measure—or that researchers so far haven’t tried to measure. Scientists often assume they can target the effects of tDCS by stimulating only the part of the brain relevant to the task that the subject is concentrating on. But most would admit there’s some guesswork involved, since brain topography can vary from one person to the next. And Reiner warns that there’s no guarantee the subject’s mind won’t wander, say, to ‘something horrific that occurred earlier today.’ What if tDCS ends up forging traumatic connections along with useful ones?”

Tags: Peter Reiner, Will Oremus

The opening of an Economist report about H7N9, a scary new strain of avian flu that has yet to display the capacity for spreading from human to human:

“WU LIANGLIANG went to hospital on March 1st with a tickly cough. After a number of hours hooked up to a saline drip, the 27-year-old pork butcher went home. When he still felt poorly a few days later Mr Wu returned to hospital and was diagnosed with a pulmonary infection. But then instead of recovering, as was expected for a man his age, Wu’s condition worsened rapidly. On March 10th, he became the second person known to have been killed by H7N9, a novel strain of avian flu not previously seen in humans.

There are now nine identified human cases of H7N9 in the Yangzi delta region, which includes Shanghai, three of which have been fatal. The most recent death reported, announced on April 3rd, was a 38-year-old chef, surnamed Hong, who died in late March. Mr Hong worked in Jiangsu, the province next to Shanghai where four of the other people who contracted H7N9 live (a nearly real-time map endeavours to track the cases). The remaining cases are all in critical condition, but in general they have not deteriorated as swiftly as Mr Wu did. A 35-year-old woman in Anhui province is still alive 22 days after she first became ill.

Many questions surround H7N9’s origin, pattern of infection and treatment (there is no vaccine). Early analyses of the genetic sequence of the virus, which the Chinese authorities have shared with the world, suggest that a familiar strain of avian flu has mutated. Previously infectious only to birds, H7N9 appears now to be able to bind with mammalian cells, making it possible to jump from chickens to animals such as pigs. The World Health Organization (WHO) maintains that that there is no evidence of ongoing human-to-human transmission. If the virus were well adapted to jump between humans, the thinking goes, clearer evidence of transmission would already have emerged among the victims’ close contacts.”

Facing climate change and the cataclysms it may bring, can we–and should we–geoengineer our way out of the situation, essentially taking control of the weather? It’s a question explored by Adam Corner in an Aeon essay. An excerpt:

“Officially, climate policy is all about energy efficiency, renewables and nuclear power. Officially, the target of keeping global temperatures within two degrees of the pre-industrial revolution average is still in our sights. But the voices whispering that we might have left it too late are no longer automatically dismissed as heretical. Wouldn’t it be better, they ask, to have at least considered some other options — in case things get really bad?

This is the context in which various scary, implausible or simply bizarre proposals are being put on the table. They range from the relatively mundane (the planting of forests on a grand scale), to the crazy but conceivable (a carbon dioxide removal industry, to capture our emissions and bury them underground), to the barely believable (injecting millions of tiny reflective particles into the stratosphere to reflect sunlight). In fact, the group of technologies awkwardly yoked together under the label ‘geoengineering’ have very little in common beyond their stated purpose: to keep the dangerous effects of climate change at bay.

Monkeying around with the Earth’s systems at a planetary scale obviously presents a number of unknown — and perhaps unknowable — dangers. How might other ecosystems be affected if we start injecting reflective particles into space? What would happen if the carbon dioxide we stored underground were to escape? What if the cure of engineering the climate is worse than the disease? But I think that it is too soon to get worked up about the risks posed by any individual technology. The vast majority of geoengineering ideas will never get off the drawing board. Right now, we should be asking more fundamental questions.”

Tags: Adam Corner

Los Angeles is the first city in the world to synchronize all of its streetlights, which will only ease congestion a little but even that much will eat away at carbon emissions. From Ian Lovett in the New York Times:

“Built up over 30 years at a cost of $400 million and completed only several weeks ago, the Automated Traffic Surveillance and Control system, as it is officially known, offers Los Angeles one of the world’s most comprehensive systems for mitigating traffic.

The system uses magnetic sensors in the road that measure the flow of traffic, hundreds of cameras and a centralized computer system that makes constant adjustments to keep cars moving as smoothly as possible. The city’s Transportation Department says the average speed of traffic across the city is 16 percent faster under the system, with delays at major intersections down 12 percent.

Without synchronization, it takes an average of 20 minutes to drive five miles on Los Angeles streets; with synchronization, it has fallen to 17.2 minutes, the city says. And the average speed on the city’s streets is now 17.3 miles per hour, up from 15 m.p.h. without synchronized lights.

Mayor Antonio R. Villaraigosa, who pledged to complete the system in his 2005 campaign, now presents it as a significant accomplishment as his two terms in office comes to an end in June. He argued that the system would also cut carbon emissions by reducing the number of times cars stop and start.”

Tags: Ian Lovett

Because all the poor people finally have sufficient food and shelter, we felt it was now appropriate to invent a hovercraft golf cart. I wish this were an April Fool’s Day joke, but it appears to be real. After a relaxing nine holes, let’s go to potter’s field and dig up dead beggars and use their bones to batter the current beggars.

Tags: Bubba Watson

Speaking of future matters, Robin Hanson at Overcoming Bias examines a survey that tried to gauge what aspects of tomorrow people of today care about. An excerpt:

“In fact, most people can hardly be bothered to care about the distant future world as a whole, and to the extent they do care, a recent study suggests that the main thing they care about from the above list is how warm and moral future folks will be. That is, people hardly care at all about future poverty, freedom, suicide, terrorism, crime, poverty, homelessness, disease, skills, laziness, or sci/tech progress. They care a bit more about self-enhancement (e.g., success, pleasure, wealth). But mostly they care about benevolence (warmth & morality, e.g., honesty, sincerity, caring, and friendliness).”

Tags: Robin Hanson

From a Rodney Brooks essay in the Futurist about the next wave of manufacturing by robotics, which will bring both good and bad things to the world:

“The first industrial robot developed in the United States went to work in 1961 in a Ewing, New Jersey, GM factory. Called the Unimate, it operated with a die-casting mold placing hot, forged car parts into a liquid bath to cool them. At the time, you couldn’t have a computer on an industrial robot. Computers cost millions of dollars and filled a room. Sensors were also extremely expensive. Robots were effectively blind, very dumb, and did repeated actions following a trajectory.

If you’ve watched the evolution of industrial robots over the last 50 years, you haven’t actually seen much innovation since the Unimate. These machines perform well on very narrowly defined, repeatable tasks. But they aren’t adaptable, flexible, or easy to use. Nor are most of these machines safe for people to be around.

Today, 70% of the industrial robots in existence are in automobile factories. They’re either in the paint shop or the body shop. Go to a car factory in Japan or Detroit, you’ll see a body shop full of robots, but with no people. Go to final assembly and you’ll find all people, no robots. Industrial robots and people don’t mix.

These machines are often heralded as money savers for factory owners and operators. But the cost to integrate one of today’s industrial robots into a factory operation is often three or five times the cost of the robot itself. It’s a job that demands programmers, specialists, all sorts of people. And they have to put safety cages around the robots so that the robots don’t strike people while operating.

Unlike human workers, who can detect when they’re about to hit something with their eyes, ears, or skin, most of these machines have no sensors or means to detect what is happening in their environment. They’re not aware. All of this speaks to a larger and fundamental flaw with the way factory bots are built today.

In an increasingly interconnected world, industrial robots have not followed the information technology revolution. In our march to the future, we somehow left robots behind. Some colleagues and I decided to change that.”

Tags: Rodney Brooks

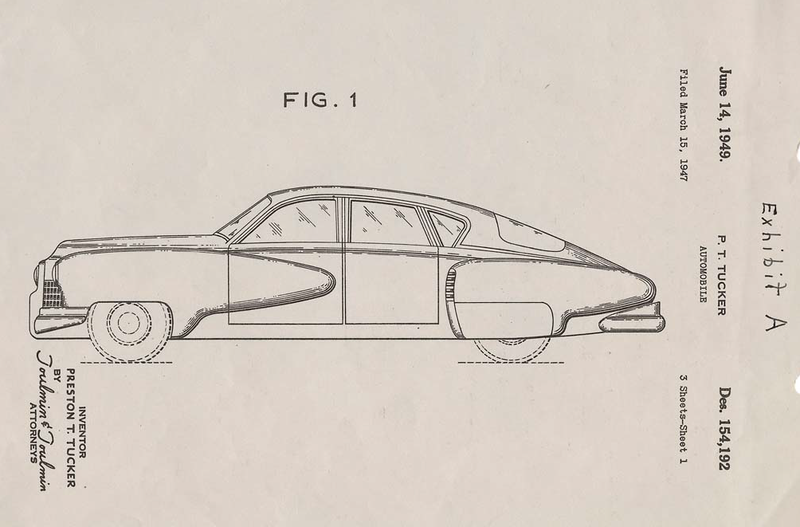

Fun 1948 PR film from Preston Tucker about his machine, a new sedan nicknamed the “Tucker Torpedo,” which revolutionized the American automobile, before the SEC and rumors of wrongdoing forced it off the road.

Tags: Preston Tucker

The opening of a really interesting Discover blog post by Dave Levitan, who wonders if we are technologically adept enough to predict if and when increasingly harsh weather will turn the Jersey Shore into a ghost town:

“Diamond City, North Carolina, is not actually a city, in that no one actually lives there. People did live there, though, back in 1899. That was when a major hurricane hit the community, on a small barrier island near Cape Hatteras. Homes were destroyed, animals were killed, and graves were uncovered or washed away in the storm according to a conservation group in the area. By 1902, all 500 residents in Diamond City had picked up and left.

The people there didn’t have computer climate models, or rapidly rising seas, or any understanding of increasing storm vulnerability; they just had a desire not to deal with what they assumed would be a constant problem. That problem, of course, is one that anyone living on the East Coast is confronting, especially with the waters of Hurricane Sandy still slowly receding from our coastal consciousness. The question is, when should people in New Jersey, Long Island, Maryland, and elsewhere start thinking about leaving behind their own versions of Diamond City?”

Tags: Dave Levitan

When all the bees have disappeared, we will still have robotic dragonflies to fill the air. The BionicOpter, created by Festo: “Just like its model in nature, this ultralight flying object can fly in all directions.”

Two seemingly unrelated things about contemporary American life that are related: 1) We’ve outsourced slavery–or some form of it. People in factories toil in ungodly conditions around the clock to make our cheap tech products. Undocumented workers are allowed to do our least appealing jobs–the things we “outsource” domestically–and are forgotten, except when they’re used as political pawns, made to seem like they’re “stealing” from us. 2) Digital sound has reduced us, demeaned our culture. We remove the rattle and hum to try to get closer to meaning, but much of the meaning was in the discord. The connection: The friction is missing, the dissonance buried. We forget the discomfort and that means the discomfort of others increases.

From Evgeny Morozov’s New York Times piece about life in a time when lo-fi has been tuned out:

“‘Civilization,’ wrote the philosopher and mathematician Alfred North Whitehead in 1911, ‘advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking about them.’ Whitehead was writing about mathematics, but technology, with its reliance on formula and algorithms, easily fits his dictum as well.

On this account, technology can save us a lot of cognitive effort, for ‘thinking’ needs to happen only once, at the design stage. We’ll surround ourselves with gadgets and artifacts that will do exactly what they are meant to do — and they’ll do it in a frictionless, invisible way. ‘The ideal system so buries the technology that the user is not even aware of its presence,’ announced the design guru Donald Norman in his landmark 1998 book, The Invisible Computer. But is that what we really want?

The hidden truth about many attempts to ‘bury’ technology is that they embody an amoral and unsustainable vision. Pick any electrical appliance in your kitchen. The odds are that you have no idea how much electricity it consumes, let alone how it compares to other appliances and households. This ignorance is neither natural nor inevitable; it stems from a conscious decision by the designer of that kitchen appliance to free up your ‘cognitive resources’ so that you can unleash your inner Oscar Wilde on ‘contemplating’ other things. Multiply such ignorance by a few billion, and global warming no longer looks like a mystery.”

Tags: Evgeny Morozov

The opening of Alex Williams’ short Techcrunch piece which asserts that data won’t kill narrative but rather alter it:

“I keep seeing this topic push up about how data is affecting creativity. Some say we are losing our sense of narration and storytelling. It’s not this at all. We are just experiencing a shift that other civilizations have faced when the traditional means for storytelling transform to give a sense of the changing times facing society.

That does not mean a rejection of the narrative form. The ancient Greeks developed a rich oral tradition for telling stories. Out of that they created a common language, which formed the foundation for fables, legends and myths.

Now we see that data, shaped by software, creates a space to tell stories in new ways. Narrative methods to express our imagination will change as techniques emerge that allow us to use programming languages to carry on what we know for the next generations.”

Tags: Alex Williams

In his frothing and scattershot New York Times op-ed piece, onetime Reagan budget director David Stockman isn’t wrong about everything. That’s because when you essentially say that everything is horrible, you’re bound to be right some of the time. It’s one of the loonier things to appear in the Times in recent memory, ignorant of history–as if the U.S. economic system was just a little “bumpy” before Roosevelt’s New Deal ruined it all–and dishonest about government investment (the Internet, which was shepherded by the public sector, seems to have grown sort of popular). An excerpt:

“So the Main Street economy is failing while Washington is piling a soaring debt burden on our descendants, unable to rein in either the warfare state or the welfare state or raise the taxes needed to pay the nation’s bills. By default, the Fed has resorted to a radical, uncharted spree of money printing. But the flood of liquidity, instead of spurring banks to lend and corporations to spend, has stayed trapped in the canyons of Wall Street, where it is inflating yet another unsustainable bubble.

When it bursts, there will be no new round of bailouts like the ones the banks got in 2008. Instead, America will descend into an era of zero-sum austerity and virulent political conflict, extinguishing even today’s feeble remnants of economic growth.

THIS dyspeptic prospect results from the fact that we are now state-wrecked. With only brief interruptions, we’ve had eight decades of increasingly frenetic fiscal and monetary policy activism intended to counter the cyclical bumps and grinds of the free market and its purported tendency to underproduce jobs and economic output. The toll has been heavy.

As the federal government and its central-bank sidekick, the Fed, have groped for one goal after another — smoothing out the business cycle, minimizing inflation and unemployment at the same time, rolling out a giant social insurance blanket, promoting homeownership, subsidizing medical care, propping up old industries (agriculture, automobiles) and fostering new ones (‘clean’ energy, biotechnology) and, above all, bailing out Wall Street — they have now succumbed to overload, overreach and outside capture by powerful interests. The modern Keynesian state is broke, paralyzed and mired in empty ritual incantations about stimulating ‘demand,’ even as it fosters a mutant crony capitalism that periodically lavishes the top 1 percent with speculative windfalls.

The culprits are bipartisan, though you’d never guess that from the blather that passes for political discourse these days.”

Tags: David Stockman

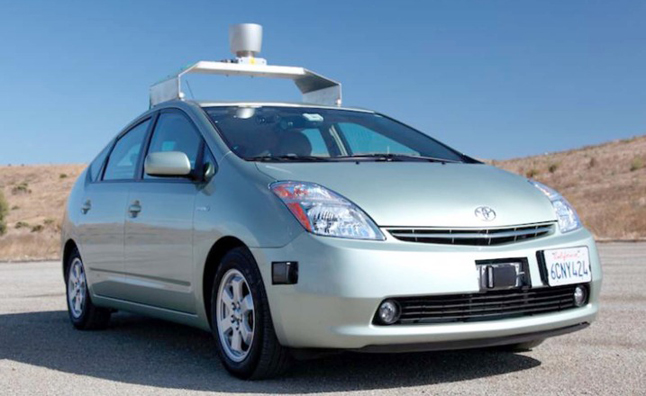

The opening of Ashlee Vance’s Businessweek piece about sharing the road with robots in Mountain View, California, ground zero for Google’s driverless car experimentation, in a time before the bots become dominant:

“My hometown, Mountain View, Calif., has become the unofficial capital of the robotic car revolution. Each day, I seem to run into one, two, or three self-driving Google cars. They’re on my freeways; they’re in my neighborhood; they’re taking my shortcuts.

One time, five of the self-driving cars gathered at a gas station equidistant from my house and Google headquarters. It felt a bit like the robots had taken ownership of my watering hole. People, likely well-paid engineers, had to fill up the cars as if they were fleshy lackeys. The rest of us waited for the robots to get full and head off to wherever it is robots go.

Away from the general unease they stir up, the Google self-driving cars come with very real consequences. I’ll concede that the cars may be better at driving than humans. They follow the rules of the road perfectly and change lanes with appropriate caution. They always signal. Thing is, the cars make the drivers around them worse.”

Tags: Ashlee Vance

If I had to say one thing about the time we’re living in, I would say this: Jesus H. Christ, our phones are great! Our phones are better than ever! I’m not sure if we’ve improved otherwise, but, wow, we’ve such progress in the area of phones!

Seriously, we seem to be making progress in a variety of ways (see the current reversal in the attitude toward gay marriage in America), but there’s still a lot of suffering and unfairness in the world. Are we moving forward or laterally–or even backwards?

John Gray, political philosopher and author of The Silence of Animals: On Progress and Other Modern Myths, believes our contention that we are moving human rights forward is self-satisfied bullshit. From an interview Gray did with Johannes Niederhauser at Vice:

“Question:

Isn’t the belief that everything will get better and that the world is now moving toward a blessed end state kind of schizophrenic, in the sense that we’ve actually been living in a deep crisis since the 1970s?

John Gray:

The rapid movement in technological advancements creates a phantom of progress. Phones are getting better, smaller, and cheaper all the time. In terms of technology, there’s a continuous transformation of our actual everyday life. That gives people the sense that there is change in civilization. But, in many ways, things are getting worse. In the UK, incomes have fallen and living standards are getting worse.

Question:

And advances in technology don’t mean that things are necessarily getting better in the grand scheme of things.

John Gray:

Oh, absolutely. Technological progress is double-edged. The internet, for example, has more or less destroyed privacy. Anything you do leaves an electronic trace.

Question:

Some people even want their mind to be transferred into the Internet to be digitally immortal.

John Gray:

That’s kind of moving in a way, but also utterly absurd. Even if it were possible to upload your whole mind on to a computer, it wouldn’t be you.

Question:

There seems to be a wide misunderstanding of what it means to be yourself.

John Gray:

Yes. You haven’t chosen to be the self that you are. You’re irreplaceable. You’re a singularity. We are who we are because of the lives that we have. And that involves having a body, being born, and dying.

Question:

Especially dying.

John Gray:

Yes, especially. A lot of contemporary phenomena, like faith in progress, is really an attempt to evade the reality of death. In actuality, each of our lives is singular and final; there is no second chance. This is not a rehearsal. It’s the real thing.”

Tags: Johannes Niederhauser, John Gray

From a Mercury News story about biological computing experimentation at Stanford University:

“In the foreseeable future, humans might carry microscopic natural computers inside their cells that could guard against disease and warn of toxic threats based on a Stanford research achievement.

A team of engineers there has invented genetic transistors, completing a simple computer within living cells, a major step forward in the emerging field of synthetic biology.

The startling achievement, to be unveiled in Friday’s issue of the journal Science, presages the day when ‘living computers’ inside the human body could screen for cancer, detect toxic chemicals or even turn cell reproduction on and off.

‘We’re going to be able to put computers inside any living cell you want,’ said lead researcher Drew Endy of Stanford’s School of Engineering.

‘We’re not going to replace the silicon computers. We’re not going to replace your phone or your laptop,’ he said. ‘But we’re going to get computing working in places where silicon would never work.

‘Any place you want a little bit of logic, a little bit of computation, a little bit of memory — we’re going to be able to do that,’ said Endy.”

Tags: Drew Endy

From a smart David Bauer essay at Medium that points out the folly of attaching “the future” to a specific date, like the year 2000, when the next wave actually arrives all the time:

“You wake up at 7am on a wonderful morning in early 2000. Dreamy as you are, you grab your phone to check the news and your email. Well, the news is that no one has texted you while you were sleeping and that your phone doesn’t connect to the internet. Because, well, you don’t have a smartphone. Just like everyone else doesn’t. Actually, a bestselling mobile phone launched in 2000 looked like this. You could still play a round of Snake, though.

After a refreshing shower — pretty much like you remember it from 2013 — you make yourself comfortable at the breakfast table. You’re an early adopter, so you have your laptop right there with you to check the news. While you wait for the computer to start up, you have time to brew some coffee.

Time to check Twitter for the latest…ah well, no Twitter yet. So let’s see what your friends are up to over on Face…doesn’t exist either. Not even MySpace. Heck, not even Friendster.” (Thanks Browser.)

Tags: David Bauer

For most of his life, Buzz Bissinger was a Brooks Brothers-clad, rage-filled asshole given to inappropriate utterances, so he decided to change his wardrobe. From “My Gucci Addiction,” the journalist’s extreme self-portrait in GQ, which focuses on shopping and fucking:

“It is safe to assume that when someone buys more than half a million dollars of clothing in three years, it isn’t simply beautiful clothing that he seeks. My wife and I realized several years ago that we had run our sexual course. It was on the surface a strange decision, since both of us were highly sexualized. And great lovers to each other. And she was absolutely beautiful. But the twin killers of menopause and boredom had set in, as they do in every marriage. And I had never been able to equate sex with intimacy.

I had always been attracted to S&M, even at an early age, when I didn’t know what it was. My mother wore leather gloves in springtime. My first teacher in kindergarten, who probably thought I was mentally challenged because I never spoke, also wore leather gloves, and every day as she left I would watch as she slowly put them on with the stretch and pull of the fingers. My eighth-grade math teacher wore stiletto black leather boots and black hair like Elvira and spoke in dismissive clips, and I adored her, even when she dropped test results into my lap with B- circled in red at the top.

I did engage in a relationship with a dominatrix after the failure of my second marriage. I left the scene after two years. But I clearly missed it, the trappings of leather increasingly irresistible. I liked extreme feelings of restraint and taking pain. But I was also interested in everything.

My sexual appetites began to spin in all sorts of different directions. My wife and I talked about it at length. She was far more experienced than I was, and she did in high school what I longed to but could not because of the need to please others—get laid, smoke dope, go to Woodstock. Before she left for Abu Dhabi, she urged me to explore, not on the basis that we wanted some open marriage but because of her feeling that I owed it to myself, to both of us, because my unfulfilled desires, or at least what I thought might be my desires, were leading to the nastiness and the contempt toward a spouse that comes from frustration.”

Tags: Buzz Bissinger

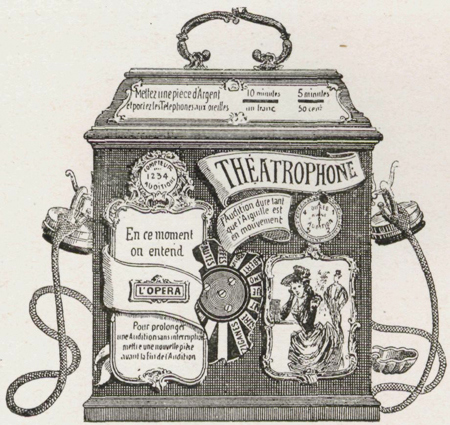

Ad-supported content just isn’t feasible for most media companies in the Digital Age. From an article about the current rise of content subscriptions by Dan Burkhart at All Things D, a passage about the Théâtrophone, which had much in common with the Telephone Herald:

“More than a century before Netflix and Hulu and Spotify first charged subscribers to satisfy their daily media cravings, another device existed called the Théâtrophone. From 1881 to 1932, telephonic devices called Théâtrophones were made available to dignitaries and guests in luxury hotels who required their daily fix of live opera performances via subscription fee — 50 centimes for five minutes.

While the Théâtrophone was an impressive invention in its day, the subscription model itself has a prolific and fascinating history of enabling innovation throughout the world. Subscriptions have helped companies pioneer new distribution models across a diverse set of business applications; all in the name of seeking efficient annuity revenue streams that outweigh the cost of production and distribution. From an end-customer ‘subscriber’ perspective, the convenience of easy access or repeat consumption can greatly outweigh the incremental cost of subscribing.

Subscriptions have historically also found ways to take on greater social meaning through the signaling of a certain status by way of access to a secret society, social club or charitable organization.”

Tags: Dan Burkhart

Algorithm-based journalism–what could go wrong? From Jesse M. Kelly at the Vancouver Sun:

“Journalist Ken Schwencke has occasionally awakened in the morning to find his byline atop a news story he didn’t write.

No, it’s not that his employer, The Los Angeles Times, is accidentally putting his name atop other writers’ articles. Instead, it’s a reflection that Schwencke, digital editor at the respected U.S. newspaper, wrote an algorithm — that then wrote the story for him.

Instead of personally composing the pieces, Schwencke developed a set of step-by-step instructions that can take a stream of data — this particular algorithm works with earthquake statistics, since he lives in California — compile the data into a pre-determined structure, then format it for publication.

His fingers never have to touch a keyboard; he doesn’t have to look at a computer screen. He can be sleeping soundly when the story writes itself.”

Just call him robo-reporter.”

Tags: Jesse M. Kelly, Ken Schwencke

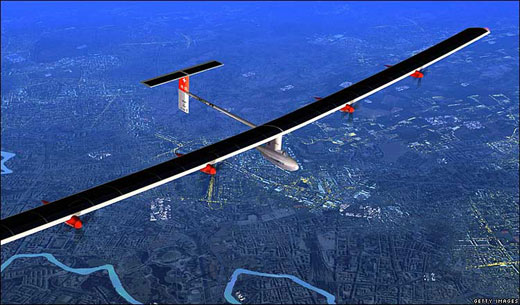

A solar-powered plane that can fly in the dark is soon going to make a cross-country flight. From Steve Henn at NPR:

“Next month, a very odd looking plane will take off from Moffett Field in Mountain View, Calif., and head east to New York. The Solar Impulse — the world’s first solar-powered plane — is capable of flying nonstop all day and all night. Its creators plan to fly it across the U.S. this spring, and by 2015 they hope to fly a similar aircraft around the world.

Its wingspan is longer than a 747 Boeing, but the entire plane weighs less than a car.

‘That was the challenge,’ says Andre Borschberg, one of the creators and a pilot. He says the wings are so large in part to generate lift and in part to create a bigger surface ‘to integrate solar cells.'”

_______________________

Solar Impulse as featured on 60 Minutes:

Tags: Andre Borschberg, Steve Henn