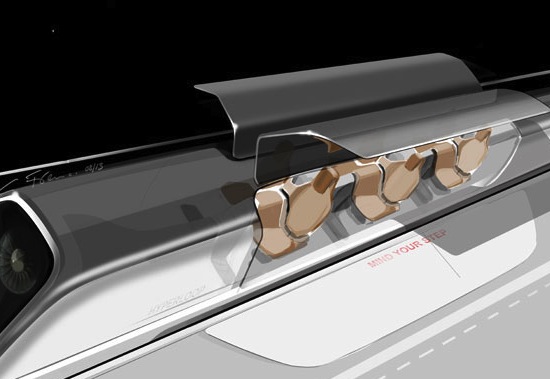

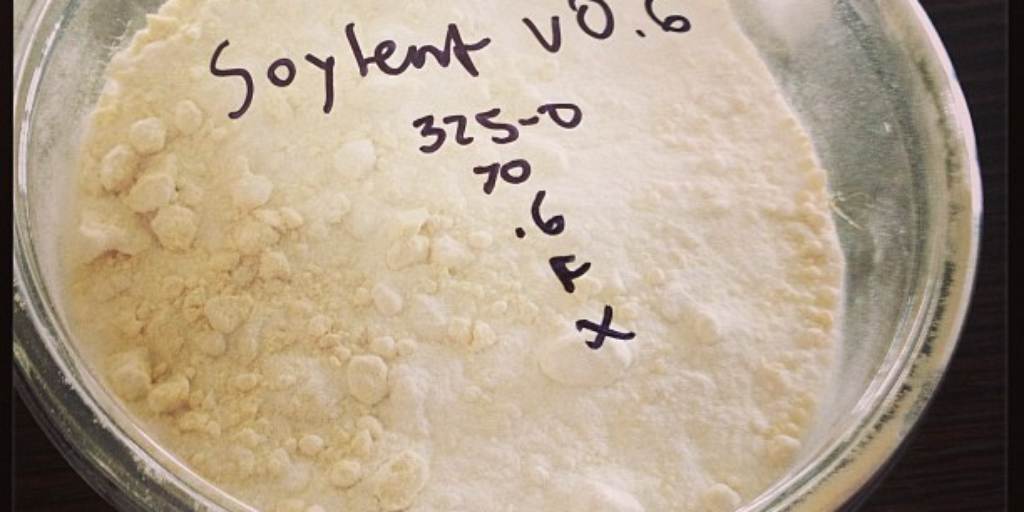

Because meat doesn’t just rain down from the heavens, the first lab-made meat was taste-tested in London recently, the burger made possible thanks to a generous donation from Google’s Sergey Brin. Isha Datar, the director of a cultured-meat research group called New Harvest, was present at the meal. She just did an Ask Me Anything at Reddit. A few exchanges follow.

_______________________

Question:

Could you make different flavors of meat?

Isha Datar:

In theory, yes, any muscle cell type could be cultured.

_______________________

Question:

Hello, I read an article in The Week yesterday about your impressive achievement. However it cited a few critics who participated in your taste test, and said that your product did not cook well because of its lack of fat. They (harshly) described it as grey and a little gross, if my memory serves. They also cited its lack of iron, do you have any comments on these criticisms, or plans to address them before your product hits the markets?

Isha Datar:

I’d like to point out first the this product is proof of concept. It’s to show that it is physically possible to culture a hamburger. It’s not practical at all right now. We need more funds to get there. There is nothing close to reaching the market just yet.Fat is something that can also be cultured and added, as is blood (where the iron could come from). This will certainly be looked at in the time to come.

The meat wasn’t really grey, because colour was enhanced with beet and saffron. But isn’t regular hamburger meat grey after cooked?

_______________________

Question:

How much time will it take for the meat to be available at the local supermarket? and will it be cheap?

Isha Datar:

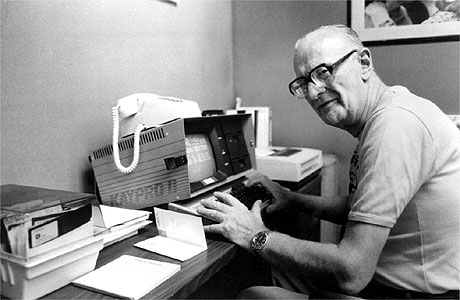

It will not start out cheap, just because of how expensive it will be. Think about how the computer trickled down into society. Highly exclusive and expensive and impractical… down to a huge proportion of the population having one in your pocket.

Not sure when everyone will have a burger in their pocket. Haha.

This first burger was $300K.. the next probably in the $10K range.. slowly moving down. The first tastings will be exclusive and expensive, slowly becoming more mainstream. Just cause technology moves that way.

_______________________

Question:

What do you say to those who, after research and understanding, still don’t want it? Do you foresee a future where this is the only type of meat available?

Isha Datar:

That’s fine if they don’t want it. But the standard price of meat can only increase with time. So they should keep that in mind.

And if they’re veg*n then no problem!

I think meat just needs to be diversified. For instance, beef is supposed to be raised on pasture that is totally unfit for farming. Hilly, rocky, steep, whatever. The problem is most beef is not produced this way. Beef is usually raised on food humans could eat (soy, corn) rather than food humans can’t eat (grass).

I personally have to problem with traditional farming. It’s just that that’s not the norm.

There should be many types of meats, and various price levels.

_______________________

Question:

As I understand, you use bovine serum (or another similar animal product) in the media for the cultured meat. Have y’all been making steps towards using media that is 100% non-animal sources? Or is that further down the road? This would be crucial for vegetarians.

Isha Datar:

It is a goal to make the serum animal-free. Research is being done on culturing mammalian cells in algae-based and mushroom-based media. But SO MUCH MORE research needs to be done in this area.It’s something that hasn’t been pushed for in the medical community, which is why the research is lagging big time.

_______________________

Question:

Since you stated that the process could be used on any animal, I suppose it’s technically possible to grow human meat. Would you ever consider it or do you think society wouldn’t be ready for the ethical debate? Would you eat your own meat?

Isha Datar:

Yes, it is technically possible. In fact it might be easier since we have so much more familiarity with human cells than the cell lines of agricultural animals.

I’d probably try my own meat. I don’t see why not.

As for society… I never know what it wants but it’s not a bad thought-experiment to engage in.•