“The instant the heart ceased to beat there was the sudden and almost uncanny diminishment in weight.”

Good science wasn’t at the heart of an experiment aimed at weighing “souls,” as recorded in an article in the March 11, 1907 New York Times:

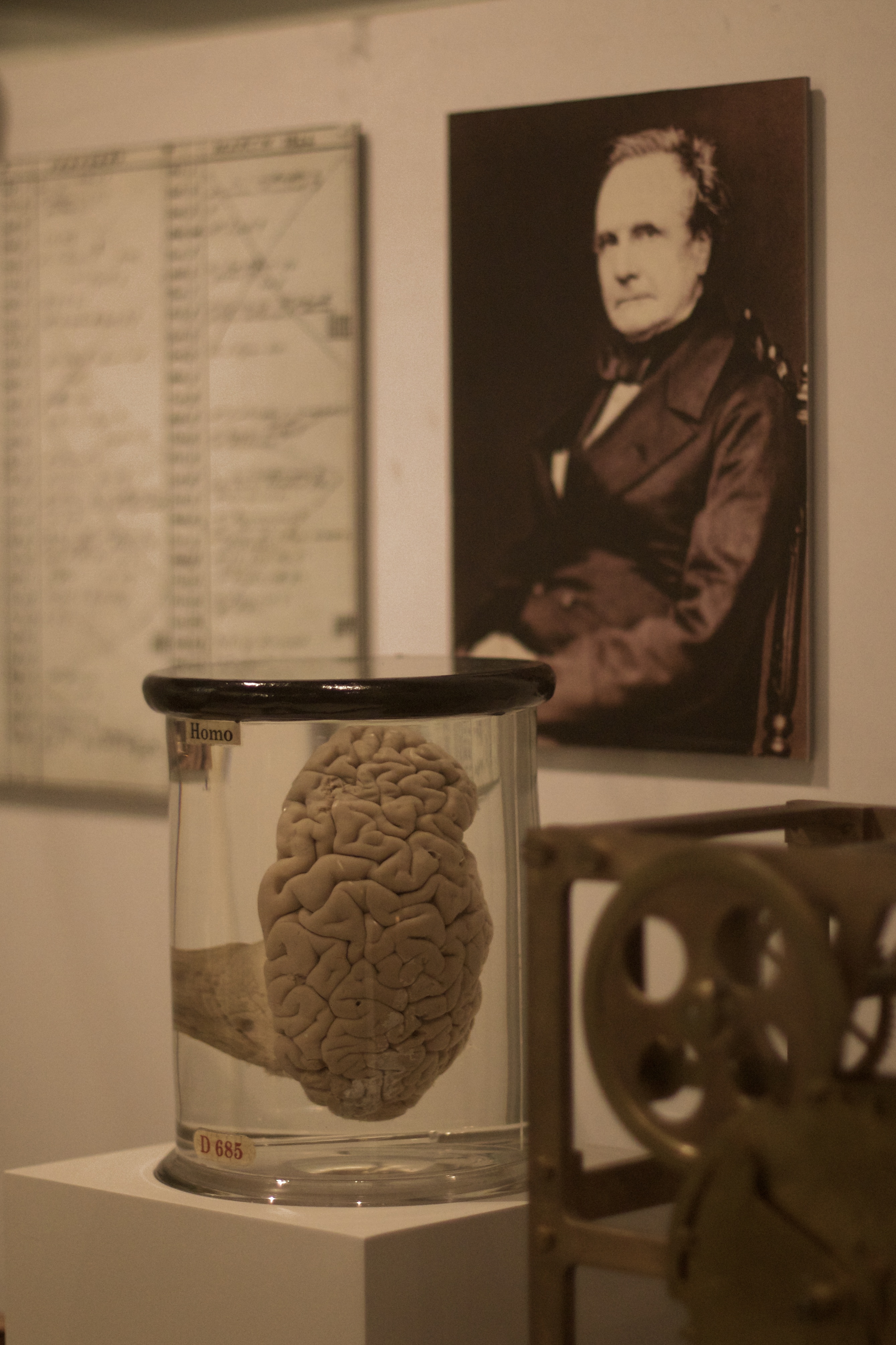

“Boston–That the human soul has a definite weight, which can be determined when it passes from the body, is the belief of Dr. Duncan Macdougall, a reputable physician of Haverhill. He is at the head of a Research Society which for six years has been experimenting in this field. With him, he says, have been associated four other physicians.

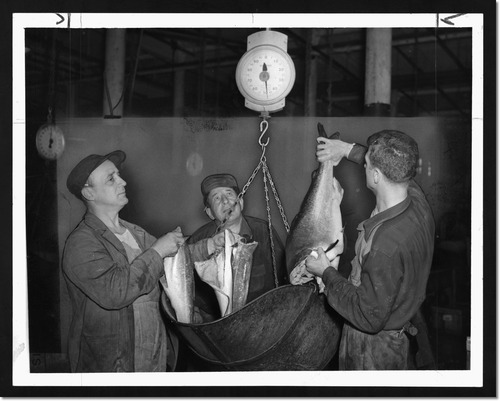

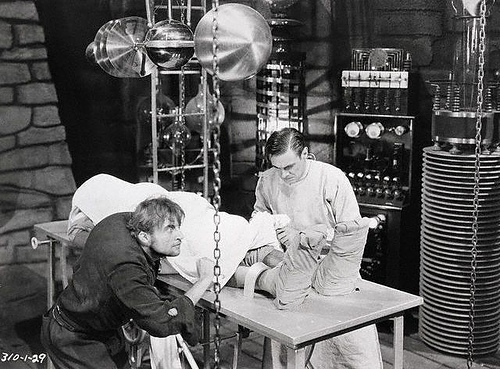

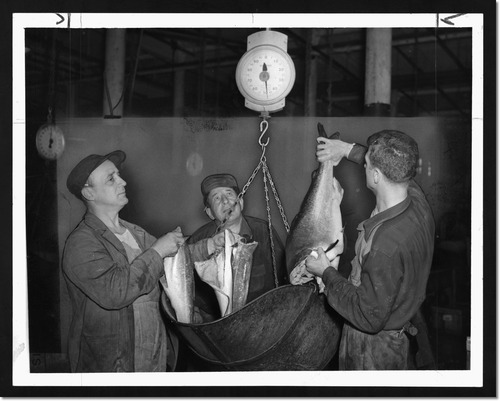

Dr. Macdougall’s object was to learn if the departure of the soul from the body was attended by any manifestation that could be recorded by any physical means. The chief means to which resort was made was the determination of the weight of a body before and after death.

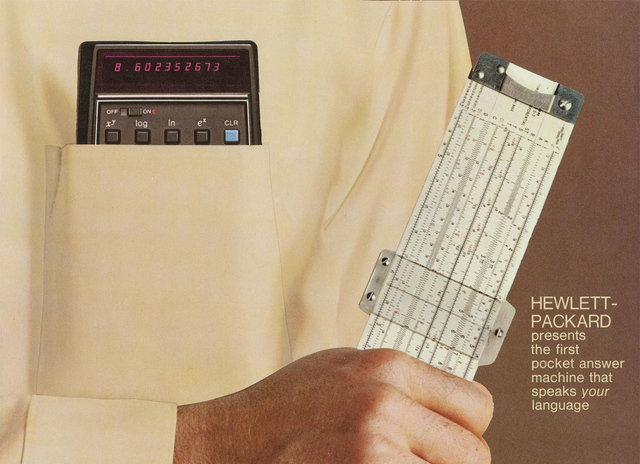

The method followed was to place a dying patient in bed upon one of the platforms of a pair of scales made expressly for the experiments, and then to balance this weight by placing an equal weight in the opposite platform. These scales were constructed delicately enough to be sensitive to a weight of less than one-tenth of an ounce. In every case after death the platform opposite the one in which lay the subject to the test fell suddenly, Dr. Macdougall says. The figures on the dial index indicated the diminishment in weight.

Dr. Macdougall told of the results of his experiments as follows:

‘Four other physicians under my direction made the first test upon a patient dying of tuberculosis. This man was one of the ordinary type of the usual American temperament, neither particularly high strung nor of marked phlegmatic disposition. We placed him, a few hours preceding death, upon a scale platform, which I had constructed and which was accurately balanced. Four hours later with five doctors in attendance he died.

‘The instant life ceased the opposite pan fell with a suddenness that was astonishing–as if something had suddenly been lifted from the body. Immediately all the usual deductions were made for physical loss of weight, and it was discovered that there was still a full ounce of weight unaccounted for.

‘I submitted another subject afflicted with the same disease and nearing death to the same experiment. He was a man of much the same temperament as the preceding patient and of about the same physical type. The same result happened at the passing of his life. The instant the heart ceased to beat there was the sudden and almost uncanny diminishment in weight.

‘As experimenters, each physician in attendance made figures of his own concerning this loss, and, at a consultation, these figures were compared. The unaccountable loss continued to be shown.

“The subject was that of a man with a larger physical build, with a pronounced sluggish temperament.”

‘But this was less remarkable than what took place in the third case. The subject was that of a man with a larger physical build, with a pronounced sluggish temperament. When life ceased, as the body lay in bed upon the scales, for a full minute there appeared to be no change in weight. The physicians waiting in the room looked into each other’s faces silently, shaking their heads to the conviction that our test had failed.

‘Then suddenly the same thing happened that had occurred in the other cases. There was a sudden diminution in weight, which was soon found to be the same as that of the preceding experiments.

‘I believe that this in this case, that of a phlegmatic man slow of thought and action, that the soul remained suspended in the body after death, during the minute that elapsed before it came to the consciousness of its freedom. There is no other way of accounting for it, and it is what might be expected to happen in a man of the subject’s temperament.

‘Three other cases were tried, including that of a woman, and in each it was established that a weight of from one-half to a full ounce departed from the body at the moment of expiration.”