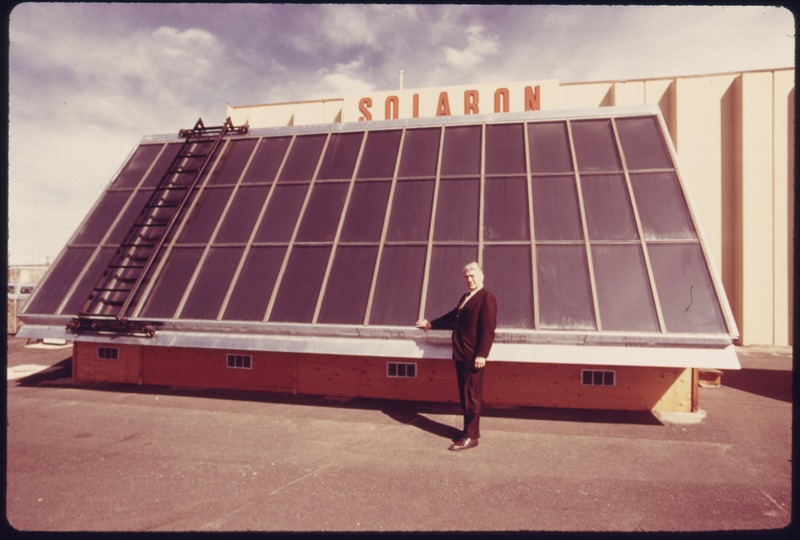

In the long run, robots will be good for us, once the pain of displacement subsides and we have figured out a way to navigate the new normal. For instance: a solar plant that doesn’t produce many jobs but offers the promise of cheap, clean energy. From Diane Cardwell in the New York Times:

“RICHMOND, Calif. — In a dusty yard under a blistering August sun, Rover was hard at work, lifting 45-pound solar panels off a stack and installing them, one by one, into a concrete track. A few yards away, Rover’s companion, Spot, moved along a row of panels, washing away months of grit, then squeegeeing them dry.

But despite the heat and monotony — an alternative-energy version of lather-rinse-repeat — neither Rover nor Spot broke a sweat or uttered a complaint. They could have kept at it all day.

That is because they are robots, surprisingly low-tech machines that a start-up company called Alion Energy is betting can automate the installation and maintenance of large-scale solar farms.

Working in near secrecy until recently, the company, based in Richmond, Calif., is ready to use its machines in three projects in the next few months in California, Saudi Arabia and China. If all goes well, executives expect that they can help bring the price of solar electricity into line with that of natural gas by cutting the cost of building and maintaining large solar installations.”