As going off the grid gets increasingly difficult, it becomes a more cherished dream. One family, Dan and Sheila and son, who took the plunge seven years ago, just did an Ask Me Anything at Reddit about the reality of such a commitment. A few exchanges follow.

_________________________

Question:

What made you go off-grid?

Answer:

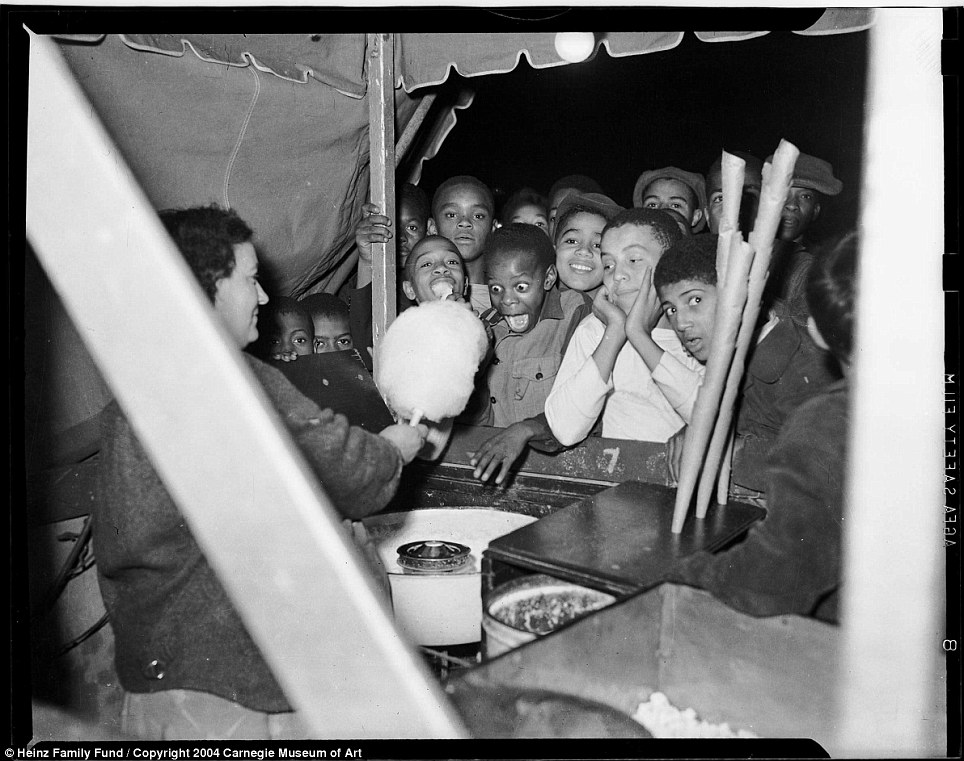

We are from Back East and our goal was always to go off the grid, away from highly populated areas, and “live the good life”. We worked our butts of for 20 years to get here.

_________________________

Question:

What was the hardest adjustment in moving away from civilization?

Answer:

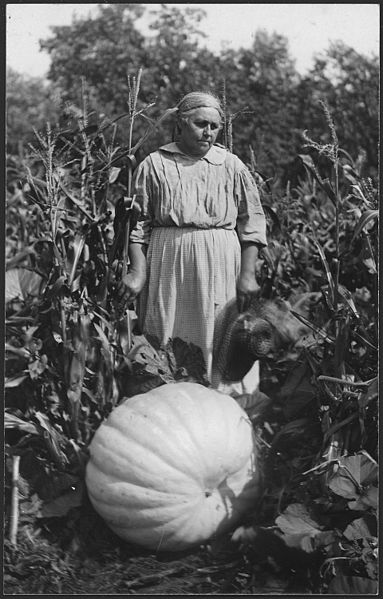

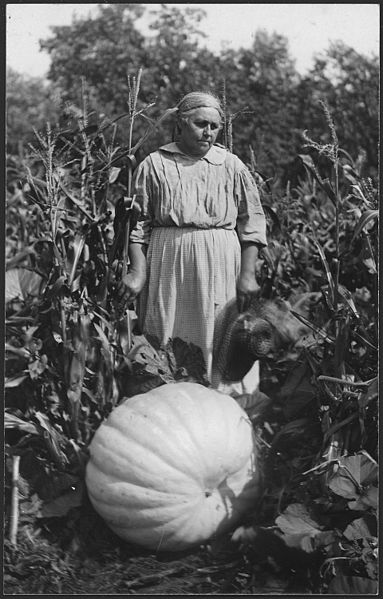

Planning food for months at a time. We can’t just go shopping any time we want, since the closest grocery store (notice I didn’t say “supermarket”) is 50 miles away.

_________________________

Question:

How “off the governmental” grid are you. How do you go about paying taxes, federal, etc.

Do you keep up with your state issued ID? Things of that nature?

Answer:

We pay our property taxes and all other taxes that we are required to do.

This being Catron County, the local government is quite non-invasive. This was once the getaway of Geronimo and his band, and Butch Cassidy and his gang, and there really isn’t much required other than “live and live,” or what we call here “the fence policy”. That is, what you do on your side of the fence is your business.

_________________________

Question:

You mention that you don’t have a car, and I was wondering what the benefit of this is other than a gesture. It seems to me that having a car provides an important option in a crisis, even if you don’t use it frivolously.

Answer:

One of the local ranchers here has lots of horses, they are always in the area, we only need to take a halter and a saddle over to one of them and we have a ride. Not having a vehicle is not the best way to go but it is what we needed to do to make this possible.

_________________________

Question:

Medical emergencies aside, how would you deal with chronic illness out there?

Answer:

This is a real concern for me as I consider moving forward – I have Crohn’s Disease, and I’m in remission which means it’s not a crisis, but I still do need to take a lot of medicine daily, and follow up with doctors/ blood work with some regularity. Would your lifestyle be able to accommodate something like this? I realize getting Crohn’s is unlikely, but as you guys get older, it’s not unreasonable to expect some problems may arise.

When we moved here I weighed 300lbs, I now weigh around 175lbs, I can say this the life will get you in shape of kill you. Around this time of day I cut wood with my son who is 22yo, I’m 60. We cut wood with a two man saw 72″ type and this will get you in shape quick.. When I first started using it I thought I would die, now in all honesty I must say that I love using it. Looking at the 8 cords of wood hand cut by myself and my son is very rewarding. I understand about cronic diseases my brother has Crohn’s disease also. But for my self my only cronic problem is a knee replacement when I was in the army over 40 years ago….. it slows me down a bit but I refuse to let it be a hindrance.

_________________________

Question:

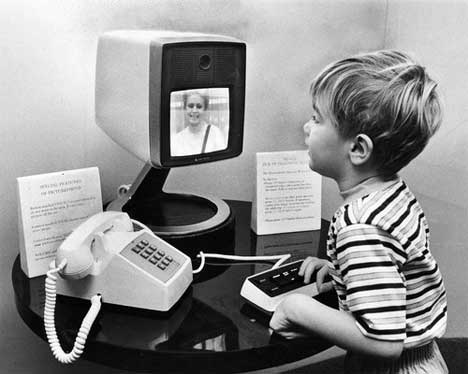

How “off the grid” can you be if you’ve got a website?

Answer:

Very, the nearest power line is over 20 miles away, no phone cell or LL and a very quiet place to be….. we have solar and use satellite internet.•