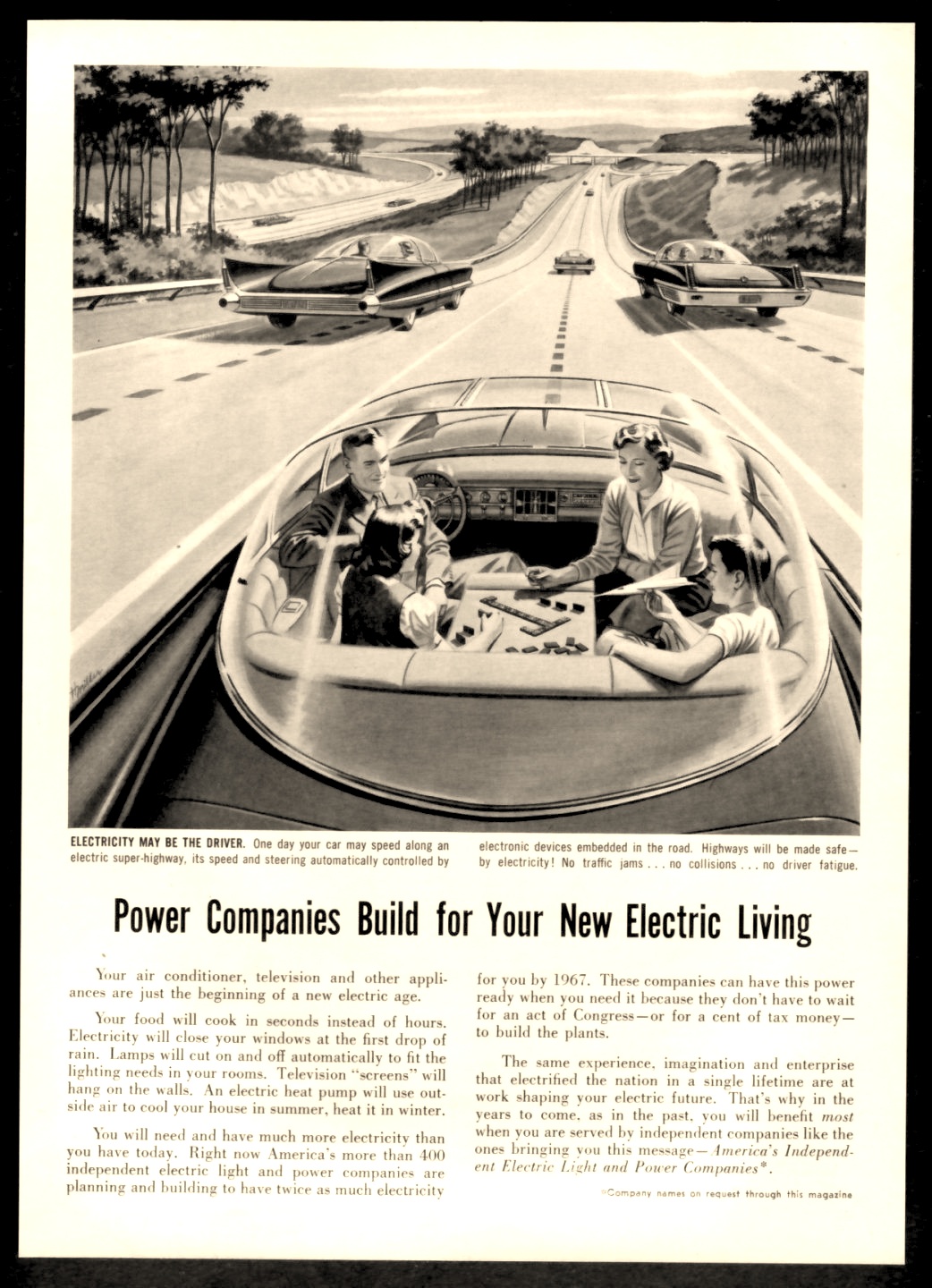

Baseball’s All-Star Game voting uses the latest technology: Paper ballots are carried by Pony Express to the General Store where they’re calculated on an abacus. Commissioner Selig then reads the results which are recorded onto a wax cylinder and played from a talking machine over the wireless. It’s a big improvement from when Charles Lindbergh used to barnstorm American cities in his aeroplane and drop leaflets with the tabulations over ballyards. From Phil Mackey at ESPN:

“But do you want to know something completely archaic and silly?

Chris Colabello — one of baseball’s best run producers through the first 30 days this season — isn’t even on Major League Baseball’s All-Star ballot.

Go ahead and take a look for yourself.

Josh Willingham, despite having played only a handful of games due to injury, is on it. So is Pedro Florimon, whose slugging percentage (.173) is lower than his weight (180).

The Colabello omission is more of a knock on MLB’s often archaic thinking than it is on the Twins.

Here’s how the process works: During the early part of spring training, each MLB front office submits projected starters at each position. Twins assistant GM Rob Antony, who was in charge of this process for the Twins, listed Joe Mauer as the first baseman, Oswaldo Arcia, Aaron Hicks and Willingham as the outfielders, and Jason Kubel as the DH. This is what they projected at the time, and if not for injuries to Arcia and Willingham, it’s possible Colabello wouldn’t have nearly as many at-bats.

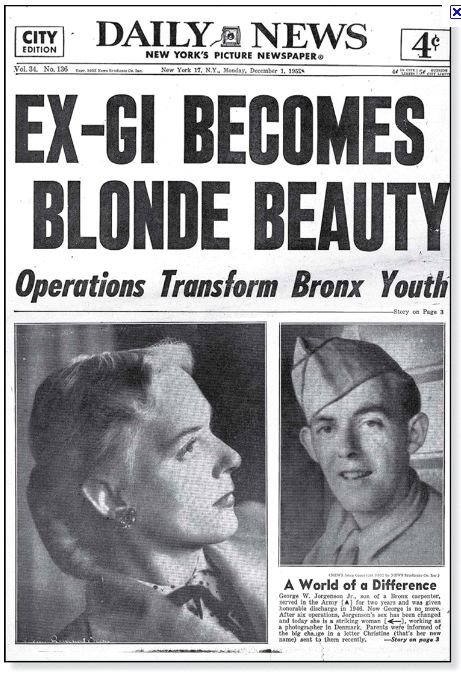

OK, that’s fine. But why can’t MLB adjust the ballot on the fly? Presumably because they already printed out millions of hanging-chad paper ballots to be distributed throughout ballparks in an era where two out of every three adults owns a smartphone in this country.

MLB can’t simply add Colabello to the online ballot?

‘Well no, that’s not the way we’ve always done it…’

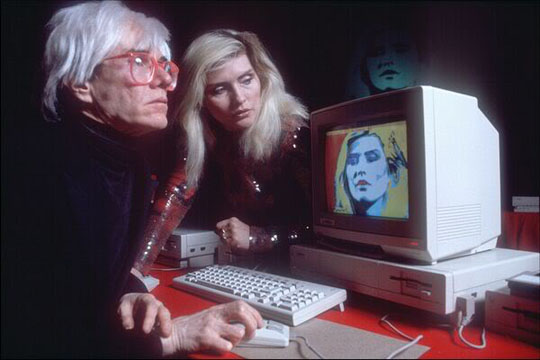

We have apps on our smartphones that allow us to record high-definition videos, we have apps that allow us to cash checks, we have apps that allow us to make dinner and movie reservations, and we have apps that essentially replace TVs, radios and books.

Yet, if we want to send Colabello to the All-Star Game at Target Field, we need to write his name in the old-fashioned way…”