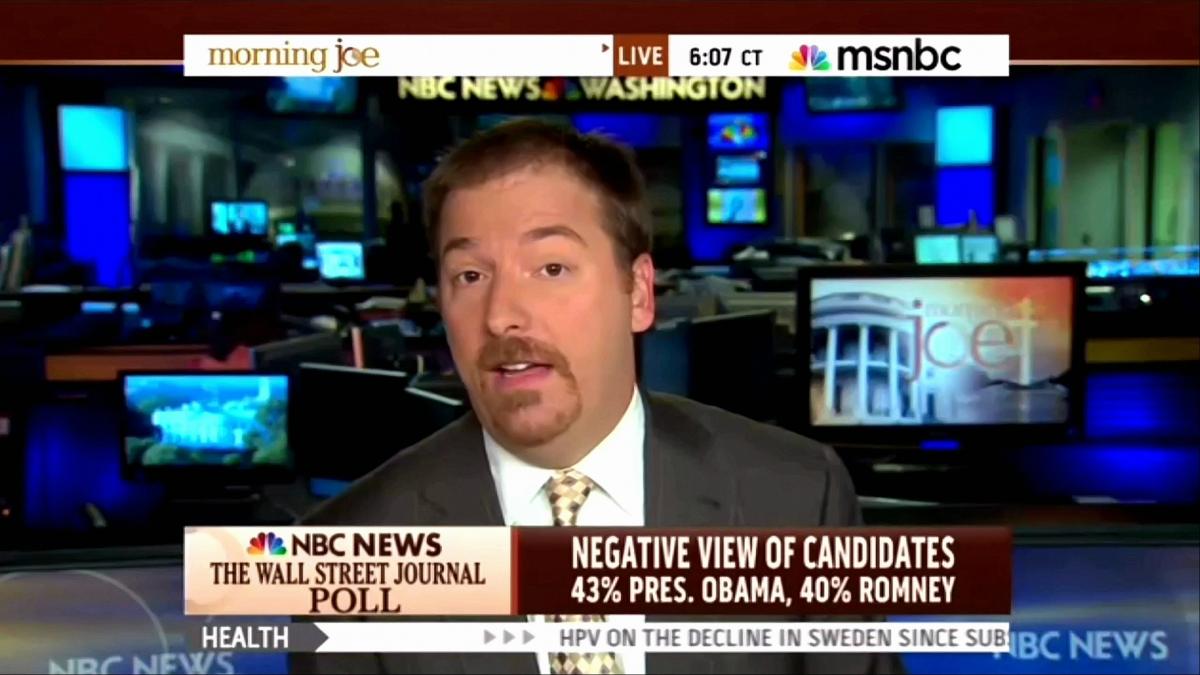

Journalism isn’t a science and while any individual organ might have its code of ethics, there is no overriding one. While that’s probably necessary, it’s alway left plenty of room for manipulators who have reduced the field, leaving it scarred and scorned with few believers. Yet the omnipresence of quasi-news like Rupert Murdoch’s outlets must have some effect, right? If you had said six years ago that President Obama would have reversed a good deal of our economic troubles, helped secure the recovery of the stock market, improved job numbers despite growing automation, kept us out of military quagmires in an exploding world, achieved something approaching universal healthcare (which seems to be good for the economy as well as good in general), heightened support for civil rights (e.g., gay marriage) and moved us in an environmentally sounder direction, and that he would do those things with an extremist opposition party controlling congress for the majority of the time, I think most Americans would have been very pleased. Yet poll after poll supposedly depicts him to be a remarkably unpopular President, with Fox News gleeful and Chuck Todd, a modified Van Dyke having a panic attack, declaring the sky is on the ground. It’s a little strange then that the two most important “polls”–the ones in November of 2008 and 2012 that involved actual polling places–were won rather convincingly by Obama. I think “winning” the media isn’t necessarily the same thing as winning, though not everyone agrees.

From Anders Herlitz’s Practical Ethics piece about the practice of news:

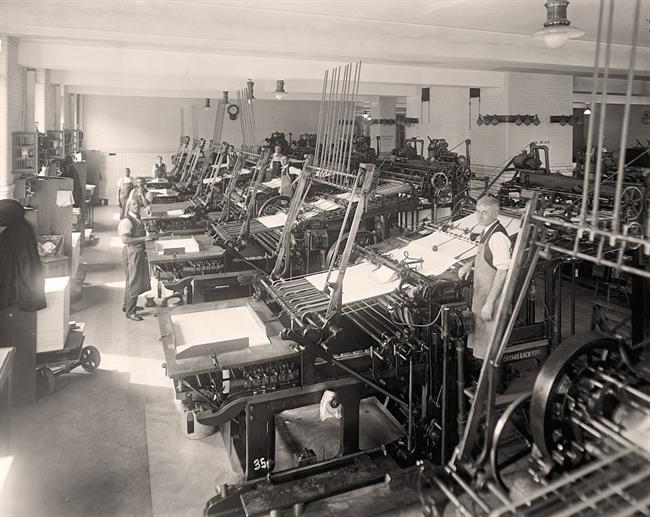

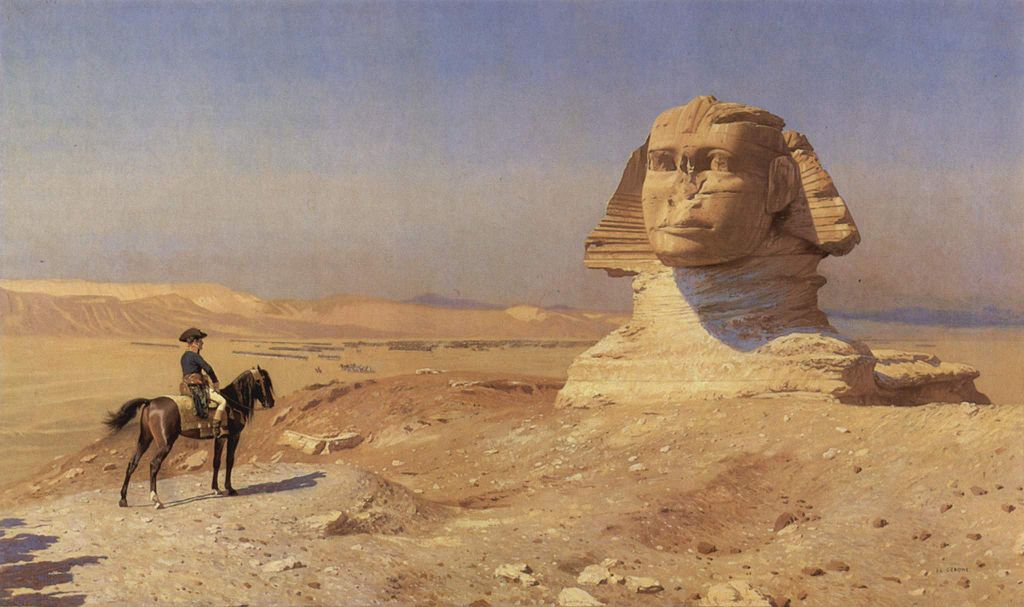

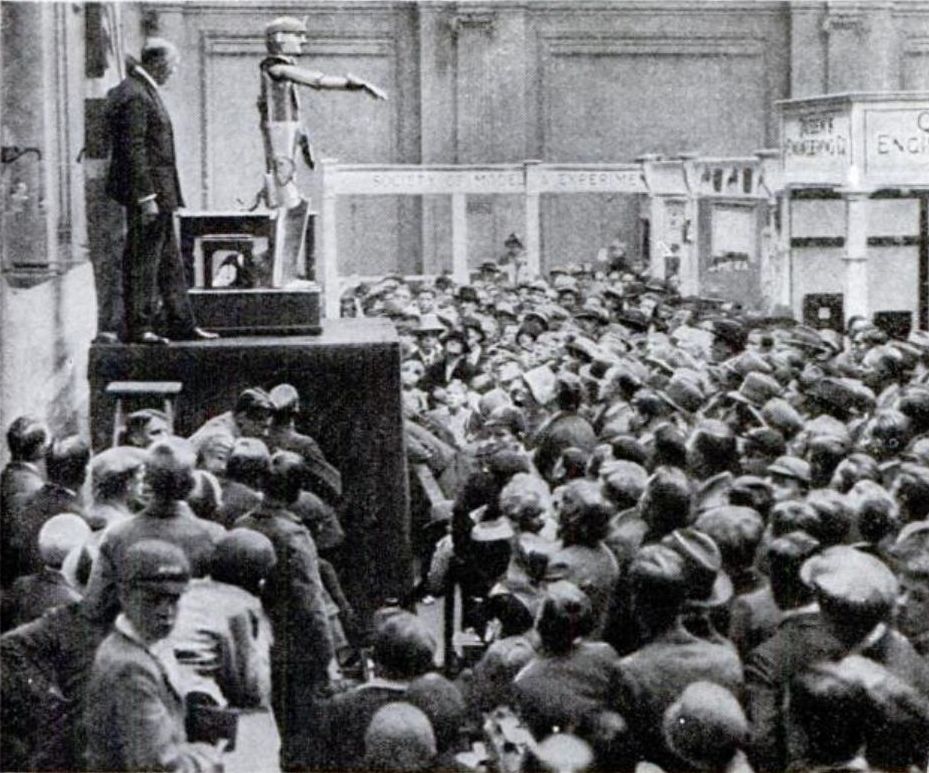

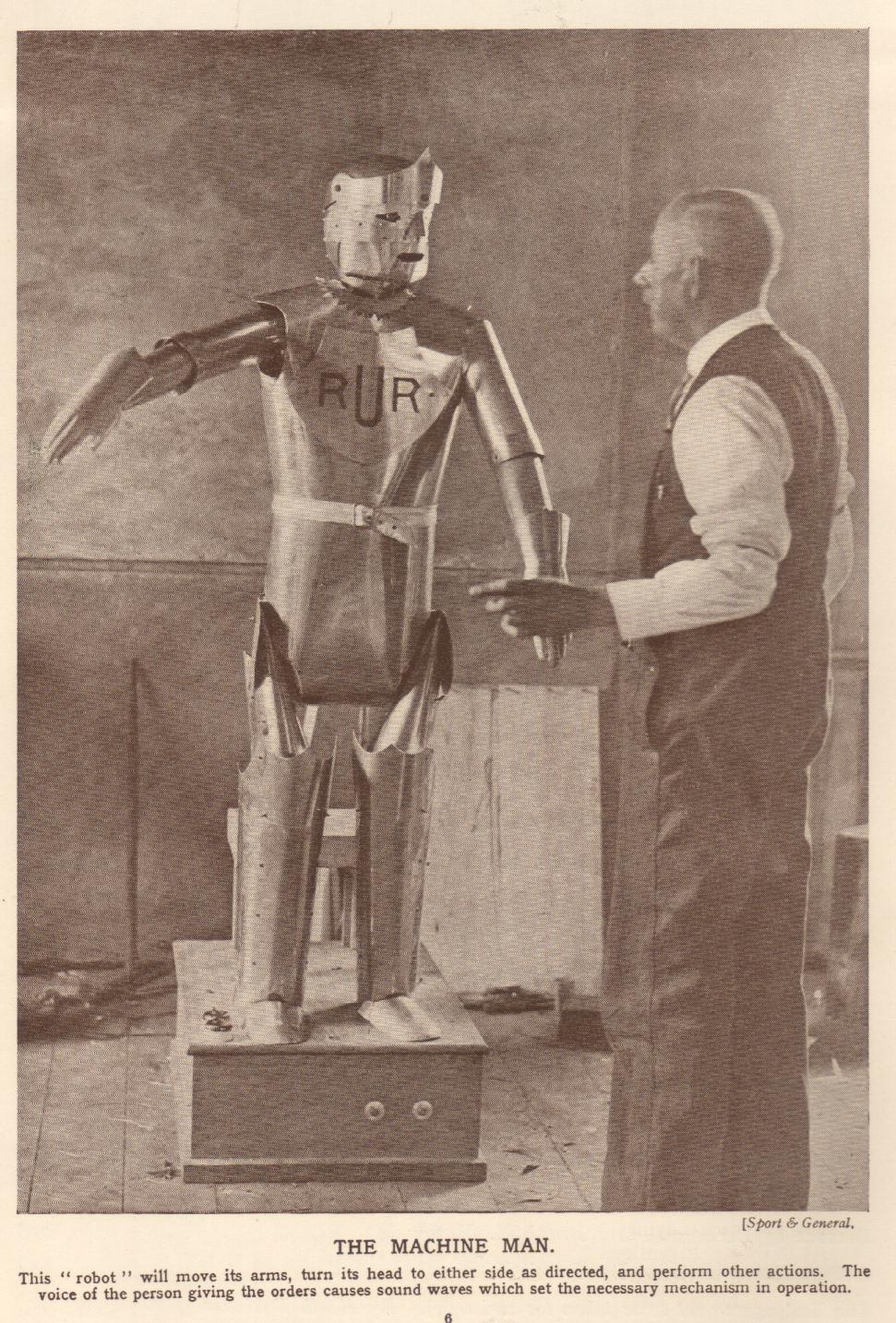

“Covering news and reporting events to a larger group of people is, from a historical perspective, very new. Newspapers with large readerships date back to the 19th century. Photojournalism became widespread in the 1930s. News in the common household’s TV starts becoming widespread in the 1950s. In the early days, to report news was to report facts, to publish an image was to give the audience the opportunity to with their own eyes see what happened in other places in the world. Journalists were witnesses to events in the world, and readers, viewers, listeners, were given the opportunity to through the journalist build their own opinions, to increase their knowledge about their countries, and about the world. Journalism and independent media outlets became a cornerstone of democracy. A well-informed people make better judgements, better choices, and this is enabled by the work of journalists. The culmination of this is the Vietnam War. Journalists were allowed to do their job, and to witness and report back to the American public what took place in Vietnam. Consequently, it became clear that news that in no way were false, untrue or fabricated could in fact generate a reaction in the public that, from the perspective of certain very powerful groups, was highly undesirable. How something is reported matter. Images matter. Details matter.

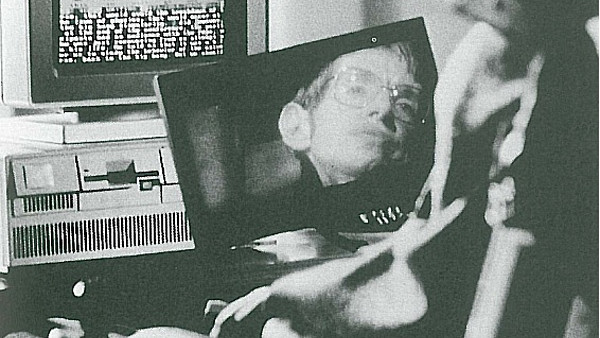

In the last couple of decades, powerful agents of the most various kind have learned to appreciate this insight to a larger and larger extent. Wars are no longer fought only on the battlefield, the success of political movements depend on what kind of media coverage they get, international relations issues depend on how the world perceives of the events, corporations know very well that they benefit from no media coverage at all of certain elements essential to their organizations (e.g. oil extraction in countries where there is no respect for human rights, assembly factories in poor countries, the origin of certain natural resources needed for the end-product), and even certain individuals are well-aware of the importance of their ‘personal brand’ and do their best to control how they are depicted in the media.”