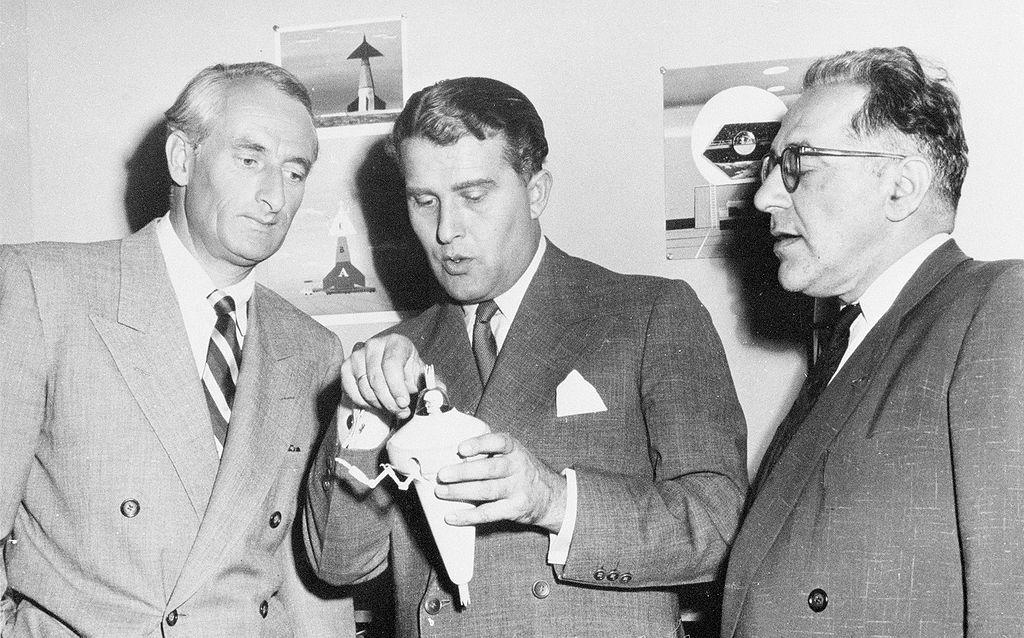

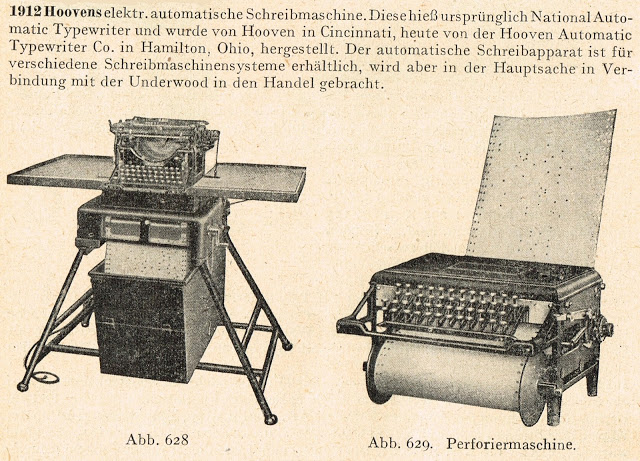

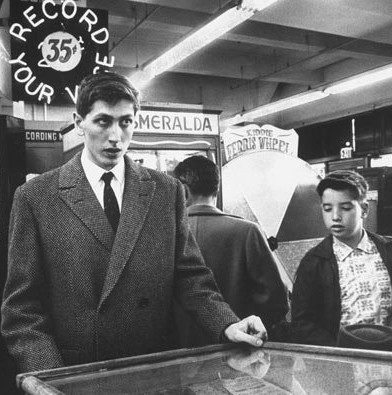

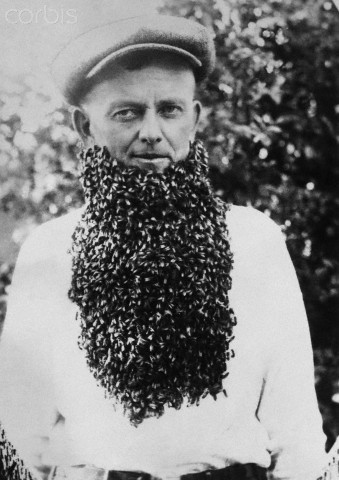

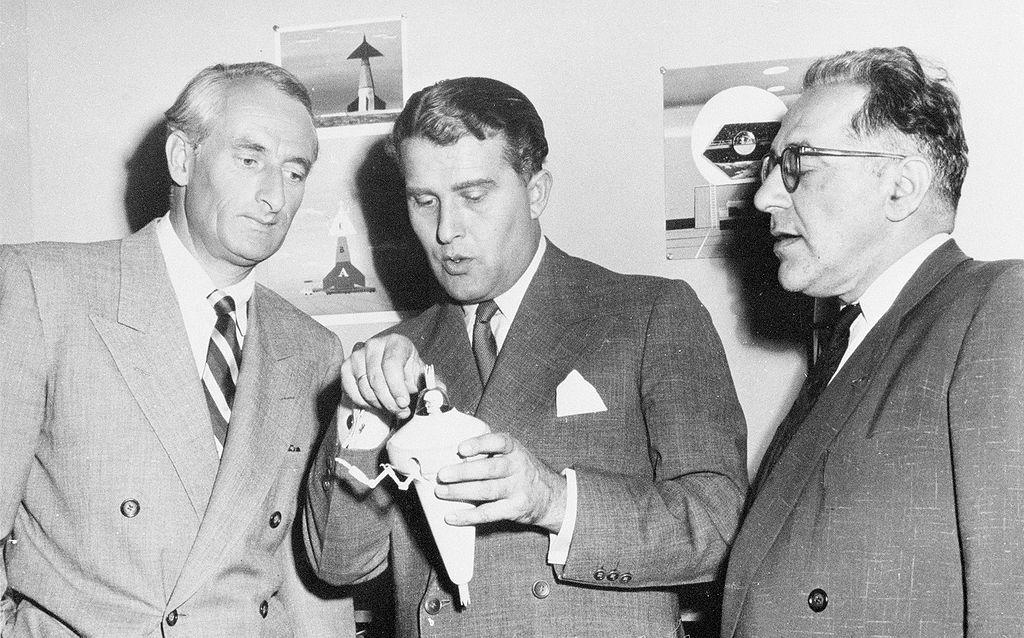

Wernher von Braun, center, with Willy Ley, right, in 1954.

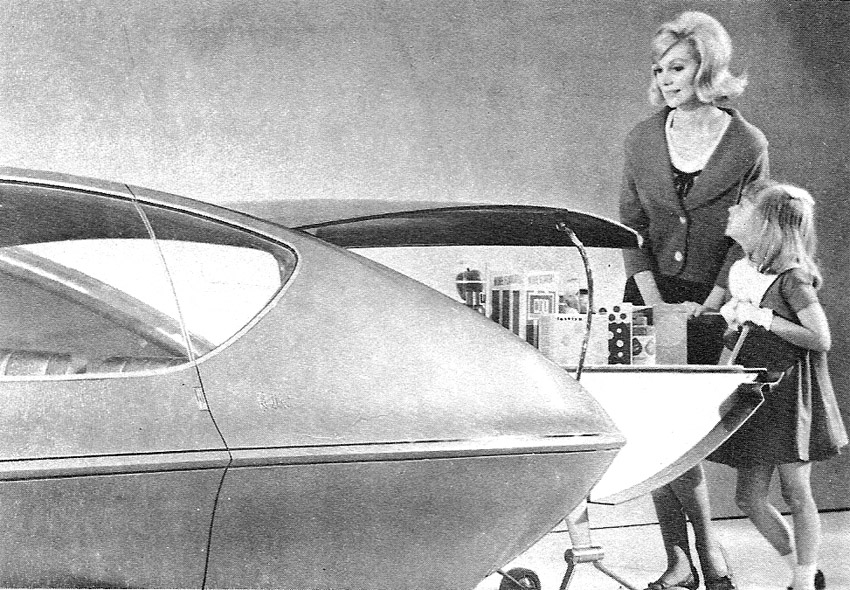

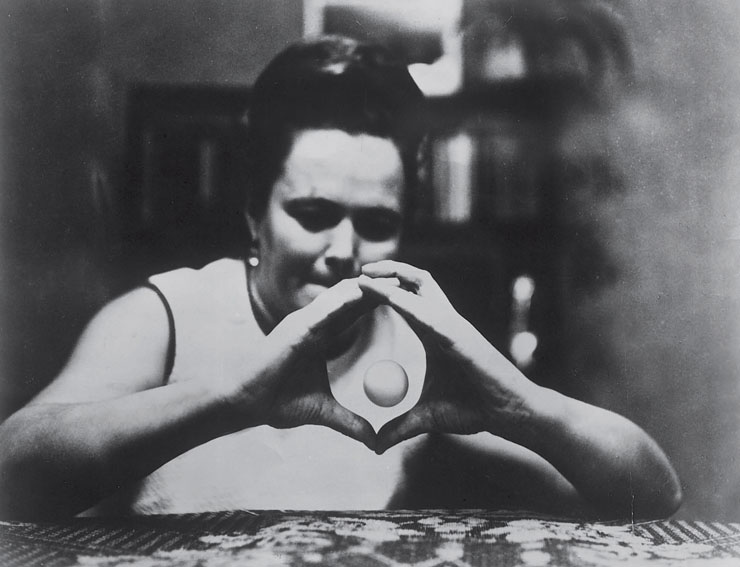

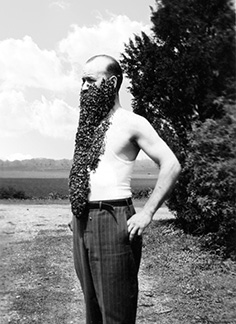

Ley with daughter Xenia at the Hayden Planetarium, 1957.

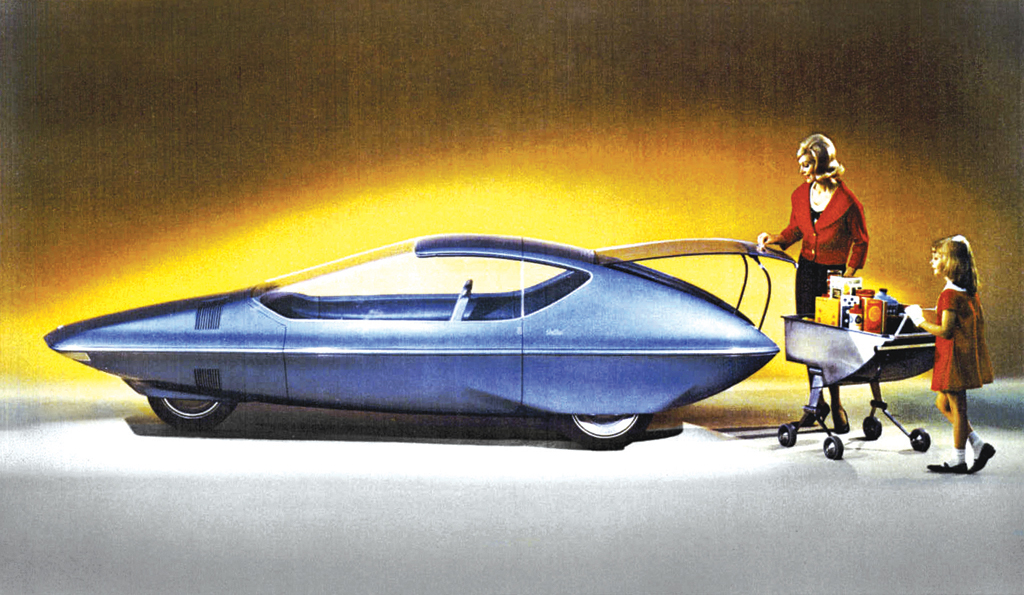

Speaking of Nazis, the top photograph offers an odd juxtaposition: That’s Wernher von Braun, a rocketeer who was a hands-on part of Hitler’s mad plan, whose horrid past was whitewashed by the U.S. government (here and here) because he could help America get a man on the moon; with Willy Ley, a German science writer and space-travel visionary who fled the Third Reich in 1935. A cosmopolitan in an age before globalization, Ley only wanted to share science across the word and encourage humans into space and onto the moon. He knew early on Nazism was madness leading to mass graves, not space stations. When Ley arrived in America after using falsified documents to escape Germany, he worked a bit on an odd rocket-related program: Ley led an effort to use missiles to deliver mail. It was a long way to go to get postcards from point A to point B, and an early attempt failed much to the chagrin of Ley, who donned a spiffy asbestos suit for the blast-off. Here’s the story of the plan’s genesis in the February 21, 1935 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

Speaking of Nazis, the top photograph offers an odd juxtaposition: That’s Wernher von Braun, a rocketeer who was a hands-on part of Hitler’s mad plan, whose horrid past was whitewashed by the U.S. government (here and here) because he could help America get a man on the moon; with Willy Ley, a German science writer and space-travel visionary who fled the Third Reich in 1935. A cosmopolitan in an age before globalization, Ley only wanted to share science across the word and encourage humans into space and onto the moon. He knew early on Nazism was madness leading to mass graves, not space stations. When Ley arrived in America after using falsified documents to escape Germany, he worked a bit on an odd rocket-related program: Ley led an effort to use missiles to deliver mail. It was a long way to go to get postcards from point A to point B, and an early attempt failed much to the chagrin of Ley, who donned a spiffy asbestos suit for the blast-off. Here’s the story of the plan’s genesis in the February 21, 1935 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

“It may be a long time before you can take a trip to the moon or to Mars in a rocket, but the time is not far off when rockets will be used to carry mail and to catapult airplanes from ships or from the ground.

This, according to Willy Ley of Berlin, who arrived today on Cunard-White Star liner Olympic for a seven-month stay in the United States, during which time he will work on the development of the rocket with G. Edward Pendray of Crestwood, N.J. Mr. Pendray is president of the American Rocket Society.

Mr. Ley said that a friend in Austria had used rockets successfully in the delivery of mail between two towns, only two and a half miles apart, but separated by high mountains. In a very short time, he said, the rocket may supplant all other means of mail delivery.

Its use as a catapult for airplanes, he said would make it possible to equip planes with smaller engines, because airplane engines now require most of their horsepower to take off and can do without it in the air. By using rocket as a catapult, this extra horsepower would not be necessary, he pointed out.

Also on the Olympic were Dr. Walter Braun, young German physician, who has come to live with his brother, Fred Braun of 468 8th St., Brooklyn; William M.L. Fiske, recently chosen captain of the American bobsled team which is to compete in the coming Olympics, who has been in Europe on business; the Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava, who will visit friends in South Carolina. The ship was a day late due to terrific headwinds it met in the crossing.”

______________________

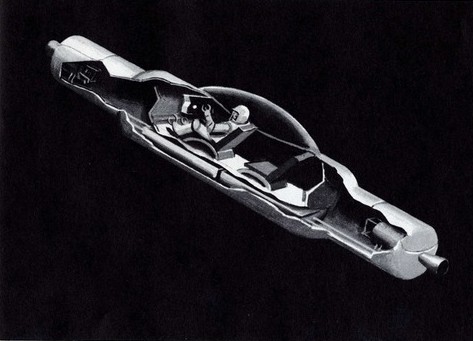

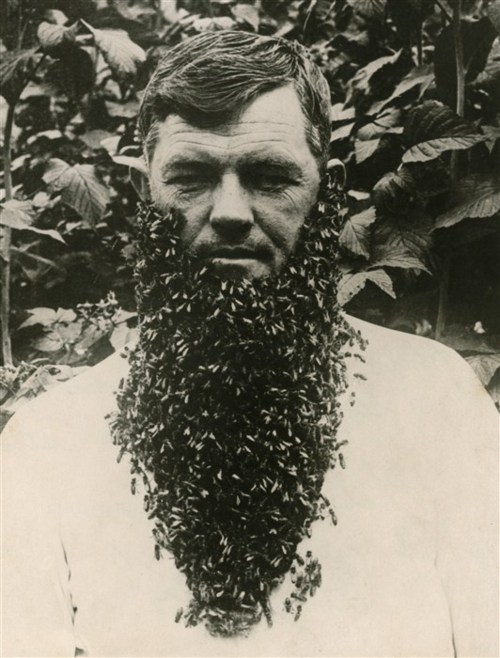

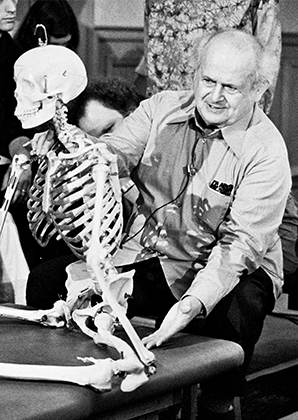

In 1952, Ley being interviewed, preposterously, about flying saucers, and also about space travel: