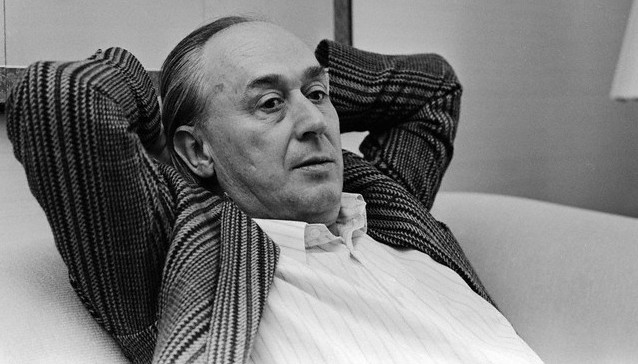

One of the best things I’ve read this year is an excellent longform conversation at the Baffler between Thomas Piketty and David Graeber, both of whom believe the modern financial system is passé, but only one of whom (Graeber) believes it’s certain to collapse. An exchange:

“Moderators:

Is capitalism itself the cause of the problem, or can it be reformed?

Thomas Piketty:

One of the points that I most appreciate in David Graeber’s book is the link he shows between slavery and public debt. The most extreme form of debt, he says, is slavery: slaves belong forever to somebody else, and so, potentially, do their children. In principle, one of the great advances of civilization has been the abolition of slavery.

As Graeber explains, the intergenerational transmission of debt that slavery embodied has found a modern form in the growing public debt, which allows for the transfer of one generation’s indebtedness to the next. It is possible to picture an extreme instance of this, with an infinite quantity of public debt amounting to not just one, but ten or twenty years of GNP, and in effect creating what is, for all intents and purposes, a slave society, in which all production and all wealth creation is dedicated to the repayment of debt. In that way, the great majority would be slaves to a minority, implying a reversion to the beginnings of our history.

In actuality, we are not yet at that point. There is still plenty of capital to counteract debt. But this way of looking at things helps us understand our strange situation, in which debtors are held culpable and we are continually assailed by the claim that each of us “owns” between thirty and forty thousand euros of the nation’s public debt.

This is particularly crazy because, as I say, our resources surpass our debt. A large portion of the population owns very little capital individually, since capital is so highly concentrated. Until the nineteenth century, 90 percent of accumulated capital belonged to 10 percent of the population. Today things are a little different. In the United States, 73 percent of capital belongs to the richest 10 percent. This degree of concentration still means that half the population owns nothing but debt. For this half, the per capita public debt thus exceeds what they possess. But the other half of the population owns more capital than debt, so it is an absurdity to lay the blame on populations in order to justify austerity measures.

But for all that, is the elimination of debt the solution, as Graeber writes? I have nothing against this, but I am more favorable to a progressive tax on inherited wealth along with high tax rates for the upper brackets. Why? The question is: What about the day after? What do we do once debt has been eliminated? What is the plan? Eliminating debt implies treating the last creditor, the ultimate holder of debt, as the responsible party. But the system of financial transactions as it actually operates allows the most important players to dispose of letters of credit well before debt is forgiven. The ultimate creditor, thanks to the system of intermediaries, may not be especially rich. Thus canceling debt does not necessarily mean that the richest will lose money in the process.

David Graeber:

No one is saying that debt abolition is the only solution. In my view, it is simply an essential component in a whole set of solutions. I do not believe that eliminating debt can solve all our problems. I am thinking rather in terms of a conceptual break. To be quite honest, I really think that massive debt abolition is going to occur no matter what. For me the main issue is just how this is going to happen: openly, by virtue of a top-down decision designed to protect the interests of existing institutions, or under pressure from social movements. Most of the political and economic leaders to whom I have spoken acknowledge that some sort of debt abolition is required.”