“Who shall say into what these automatic salesmen will develop?”

Arkady Joseph “A.J.” Sack was decades ahead of his time in scheme if not execution. The Russian-born businessperson (and historian), who had an ardor for animatronics, announced in the late 1920s that he would open a chain of automated department stores, the first to be located in Manhattan, which would feature talking robots rather than salespeople. One human would oversee the entire operation, with the machines communicating information to customers about the 150 products offered, accepting payments and thanking shoppers for their business, giving carbon-based workers the day off every day. The shops never opened.

In the March 10, 1929 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Marcia Nardi wrote an article about Sack and his helpful hardware, though the story focuses more on the robots and their sociological effects (skipping merrily past the specter of mass unemployment), rather than going into detail about the stores. (You can learn more specifics about the proposed shops here and here.) Two excerpts from the long article.

__________________________

“Before this winter is out, America will have been invaded by a whole army of salesmen-robots which have been called ‘almost human automatons,’ and of which the Associated Press says: ‘They will do everything but slap the customer on the back and ask him how his family is.’

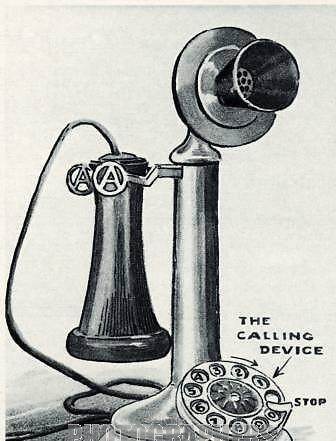

In other words now that the infant penny-in-the-slot machine, not unfamiliar to commuting subwayites, has reached maturity and adult robustness, the salesman-robot is about to take his place along with the radio and airplane as one of the marvels of the Twentieth Century.

The salesmen-robots have been devised by the Consolidated Automatic Merchandising Corporation and A.J. Sack, the chairman of the firm, looks forward to their debut into the business world with all the assurance of the Creator when he commanded Eve to spring forth from Adam’s Rib.

‘In America today,’ says Mr. Sack, ‘we look over the merchandise in our homes, through the advertising pages of newspapers and magazines. Even in our travels and pleasure excursions, we actually shop through the medium of posters and billboards. National advertising, grown to the dimensions of a billion dollar industry, sells us on hundreds of articles in advance of our seeing them.

‘Having been sold on an article because it is standardized and advertised, it is hardly logical or economical to have a human being perform the simple, mechanical operation of exchanging this article for money. An Automatic Merchandising Machine can perform this work at less expense and more promptly.'”

__________________________

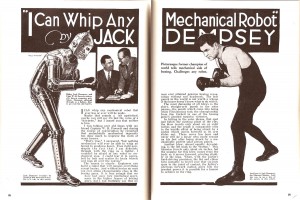

“With the inquiries and orders on hand, there will probably be a million and a half robots at work before long–mechanical men that will not only give the public what it wants in the way of service but will also add a little human touch to their purely mechanical function by saying ‘Thank you’ and by repeating the slogan connected with the merchandise they offer.

These robots will not have human forms like the robots of Captain Roberts and Captain Richards and will bear less resemblance outwardly to their English brother and sister than to their sires, the weighing and postage stamp and bar of chocolate machines, and will have much in common with the restaurants where you don’t require the smile of a pretty waitress in order to get your lunch.

But even as the automobile and airplane must smile incredulously as they contemplate their own tintypes of 1908, who shall say into what these automatic salesmen will develop?

Inventors of the future will probably perfect these machines so that they will be able to do everything a man does, but most likely they will never be able to make robots think. That is where the robots fall down, but that is also where their success lies.

We no longer need the personality of glib-tongued salesmen to influence our choice in buying small commodities. He might just as well be a mechanical man of iron and steel with electricity in his veins instead of blood for all the need the customer now has of salesmanship abilities. In the same way people in many other industries and trades have been similarly reduced to mere automatons, and perhaps some day other robots beside the salesman type will be the means of releasing that horde of countless workers whose tedious machinelike jobs in our factories and offices and telephone exchanges often leave their minds too dull and inert for any real enjoyment of their free hours.

‘Yes, these robots have an importance beyond their economic one,’ says Mr. Sack, ‘It is true, of course, that the discord between modern production and the old-fashioned methods of distribution originally prompted their invention and is responsible for their growing popularity. But it is an established fact that every step in the development of our machinery age means also, in the long run, a forward step in the development of our civilization and culture. The energy released through the application of machinery in production is already responsible for our higher standards of living, and for the development and appreciation of art, music and literature among broad masses of people. The substitution of mechanical slaves for human slaves will inevitably result in further development of cultural progress among those who will gradually be freed from the deadening monotony of a mechanical job.'”