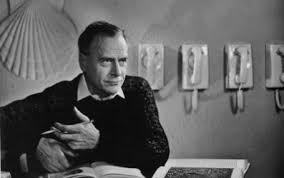

Google does many great things, but its corporate leaders want you to trust them with your private information–because they are the good guys–and you should never trust any corporation with such material. The thing is, it’s increasingly difficult to opt out of the modern arrangement, algorithms snaking their way into all corners of our lives. The excellent documentarian Eugene Jarecki has penned a Time essay about Google and Wikileaks and what the two say about the future. An excerpt follows.

_________________________

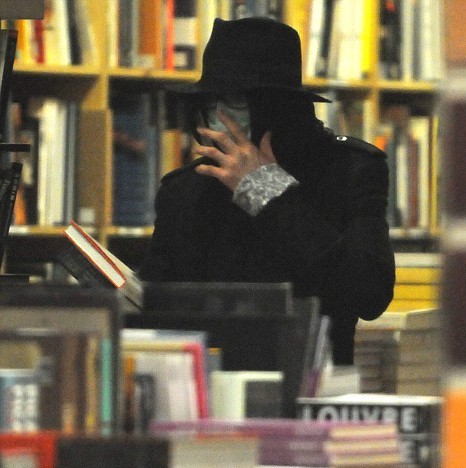

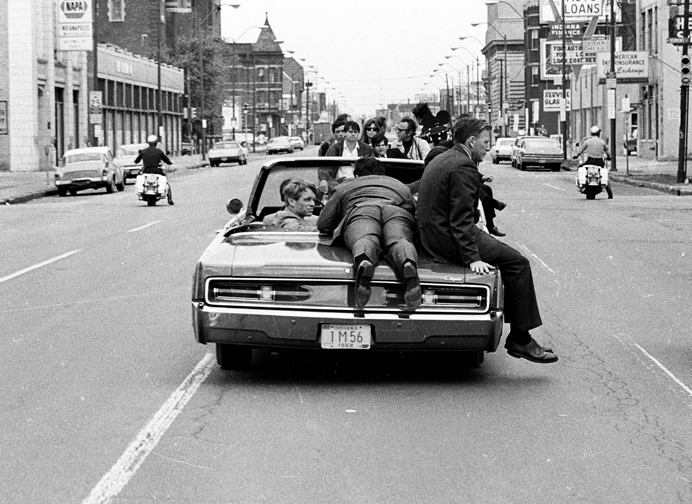

I interviewed notorious Wikileaks founder Julian Assange by hologram, beamed in from his place of asylum in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London. News coverage the next day focused in one way or another on the spectacular and mischievous angle that Assange had, in effect, managed to escape his quarantine and laugh in the face of those who wish to extradite him by appearing full-bodied in Nantucket before a packed house of exhilarated conference attendees.

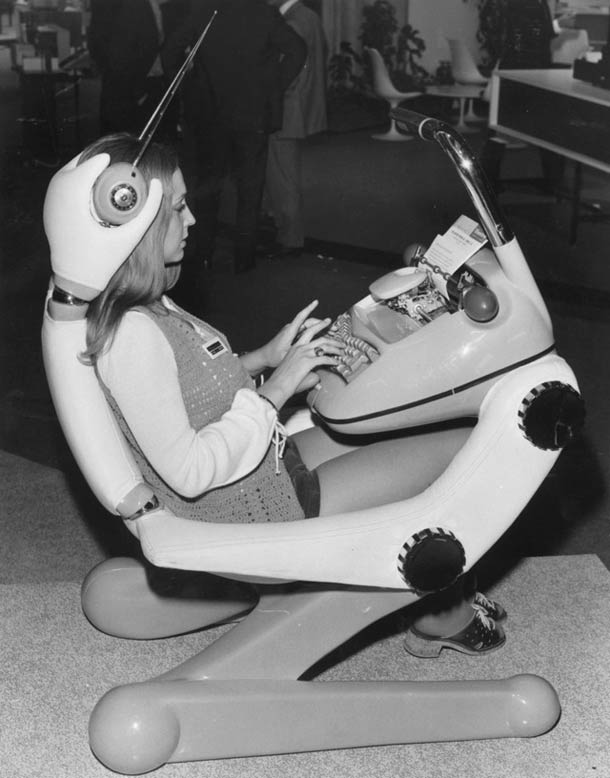

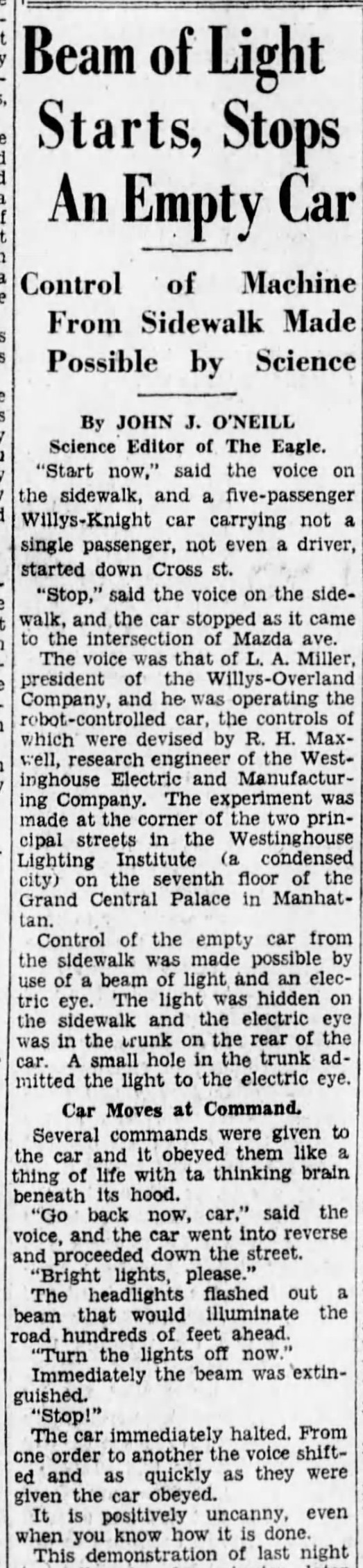

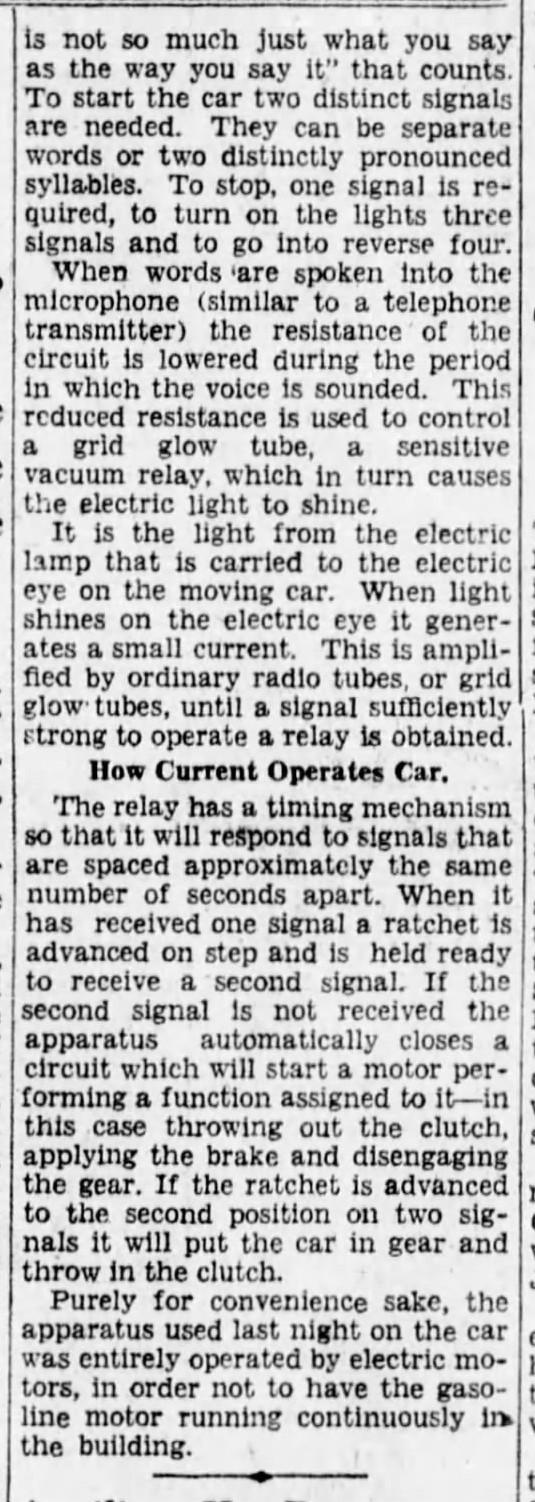

Beyond the spectacle, though, what got less attention was what the interview was actually about, namely the future of our civilization in an increasingly digital world. What does it mean for us as people to see the traditional town square go digital, with online banking displacing bricks and mortar, just as email did snail mail, Wikipedia did the local library, and eBay the mom and pop shop? The subject of our ever-digitizing lives is one that has been gaining currency over the past year, fueled by news stories about Google Glasses, self-driving cars, sky-rocketing rates of online addiction and, most recently, the scandal of NSA abuse. But the need to better understand the implications of our digital transformation was further underscored in the days preceding the event with the publication of two books: one by Assange and the other by Google Executive Chairman, Eric Schmidt.

Assange’s book, When Google Met Wikileaks, is the transcript (with commentary by Assange) of a secret meeting between the two that took place on June 23, 2011, when Schmidt visited Assange in England. In his commentary, Assange explores the troubling implications of Google’s vast reach, including its relationships with international authorities, particularly in the U.S., of which the public is largely unaware. Schmidt’s book, How Google Works, is a broader, sunnier look at how technology has presumably shifted the balance of power from companies to people. It tells the story of how Google rose from a nerdy young tech startup to become a nerdy behemoth astride the globe. Read together, the two books offer an unsettling portrait both of our unpreparedness for what lies ahead and of the utopian spin with which Google (and others in the digital world) package tomorrow. While Assange’s book accuses Google of operating as a kind of “‘Don’t Be Evil’ empire,” Schmidt’s book fulfills Assange’s worst fears, presenting pseudo-irreverent business maxims in an “aw shucks” tone that seems willfully ignorant of the inevitable implications of any company coming to so sweepingly dominate our lives in unprecedented and often legally uncharted ways.•