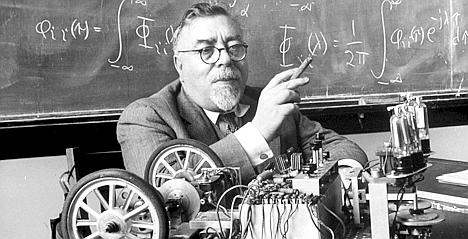

Tim Wu, the Columbia law professor who coined the term “network neutrality” and recent candidate for New York State Lieutenant Governor, just conducted a predictably intelligent and engaging Reddit Ask Me Anything.

Net neutrality, which was supported by the FCC during the Obama Administration, is likely on the chopping block with all three branches of the government in the hands of Republicans, and often extremely conservative ones at that.

Regardless of what happens in the immediate future, it’s still an idea that makes sense if we are to be a democracy with equal opportunities for all. Just imagine if there were two national highway systems, one that allowed 55 mph for those that can pay more and another that permitted 25 mph for those who were poor. While airlines offer different options–first class, business class, coach–everyone arrives at the same time. If we’re not all permitted a roughly similar ETA at reasonable cost, the inequality we’re now experiencing will only grow.

A few exchanges follow.

Question:

Do you have (in your mind’s eye) a moment when American society reached it’s proverbial “fork in the road” leading us on this dark path?

Tim Wu:

That is an interesting question. There is a danger in always thinking that previous times were “golden” and now is dark. Nonetheless I do think now has an objective sense of darkness, where fear and loathing seem to be the currency of daily life.

On the question of whether America took a fork in the road. Here are a few candidates, one public one private:

In the 1990s, when progressives (myself included) were too sanguine about the effects of trade, various forms of deregulation and other policies on the middle and working classes. It was predicted and well known that inequality would result, but the argument that we needed a bigger pie that could then be redistributed. The redistribution never came. And led to the election of a demagogue.

Private: The 1980s – 90s, when corporate leadership at large lost any sense of noblese oblige — a duty to the country and began to feel that their only real duties were to shareholders and maximization of executive compensation. I think this also led us to mass inequality, which I see as the root cause of most of what ails us today.

Question:

With a Republican in the White House, one would assume antitrust enforcement is dead, but Trump seems to be far more interventionist (starting trade wars, threatening private enterprises who cut jobs, etc) than traditional hands-off-the-market, laissez faire Republicans. Meanwhile, Obama’s own Council of Economic Advisors conceded the US economy became more concentrated under his watch. Do you think antitrust could actually improve under Trump? If possible, please break out your prognosis for both the US economy at large vs the internet economy.

Tim Wu:

It is hard to predict anything related to Trump. My main fear is that if there is more enforcement, that it is arbitrary and capricious, based on the beefs the administration has with its perceived enemies.

There is some sense, already, that Trump wants to use the Time – AT&T proposed merger to “punish” CNN — have it sold to someone who will do what he says. This is not the kind of antitrust policy that I support.

Question:

Do you think net neutrality can be reinstated if it’s lost or will it be near impossible to reinstate?

Tim Wu:

The idea will always be around.

Question:

Do you also want to make it illegal for UPS and Amazon to offer priority mail at a premium?

Tim Wu:

As it stands, premium delivery is a user-selected option that does not strike me as a major factor in competition among the vendors of goods

I would be concerned if…

(1) If there were evidence of limited bandwidth capacity in the delivery system, and evidence that UPS wanted to slow down mail generally to promote their “premium product” (2) If UPS and Amazon charged vendors, not consumers, to have things delivered faster (i.e., charged Fischer Price to deliver toys faster than its rivals) (3) If there was a sense that Amazon / UPS were likely to use premium mailing to entrench a monopoly incumbent (4) If premium mailing had a discernible effect on the quality of the product once it arrived.•