It’s crazy out there in America right now. I mean, it’s always been crazy out there in America, but there’s never been a time, not even during the Civil War, when we’ve had so many ways to blow the whole thing up, the virtual means now joining the physical ones. It’s a mad mix of traitors, colluders, enablers, conspiracists, cranks, bots, anti-government zealots and guns, guns, guns. For a few in possession of weapons, even Timothy McVeigh has reached hero status.

It’s crazy out there in America right now. I mean, it’s always been crazy out there in America, but there’s never been a time, not even during the Civil War, when we’ve had so many ways to blow the whole thing up, the virtual means now joining the physical ones. It’s a mad mix of traitors, colluders, enablers, conspiracists, cranks, bots, anti-government zealots and guns, guns, guns. For a few in possession of weapons, even Timothy McVeigh has reached hero status.

Trump’s ultimate tumble into utter disgrace may rip the seams off the whole ball, or the unpleasantness may proceed in that direction regardless. Perhaps there’s no Civil War 2.0, but there will be repercussions, large-scale shocks, especially since the Trump Administration has turned Homeland Security away from domestic threats posed by militias. That storm will only gather more easily.

Two excerpts follow, the first about a left-wing, gun-loving militia and the second about the Nevada town where it’s illegal to not own a firearm.

From Cecilia Saixue Watt’s Guardian article “Redneck Revolt“:

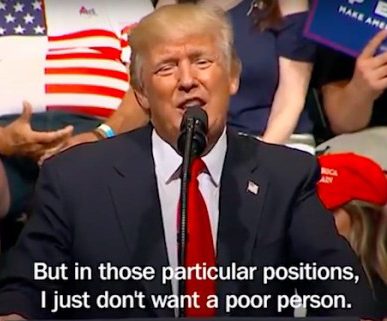

A 31-year-old activist with long hair and a full bushy beard, [Max] Neely had a full day of political activism ahead of him: Donald Trump was in Harrisburg to mark his 100th day in office with a speech at the Pennsylvania Farm Show Complex. In other parts of the city, the liberal opposition were also readying themselves: organizations such as Keystone Progress, Dauphin County Democrats and the local Indivisible group planned to march in protest.

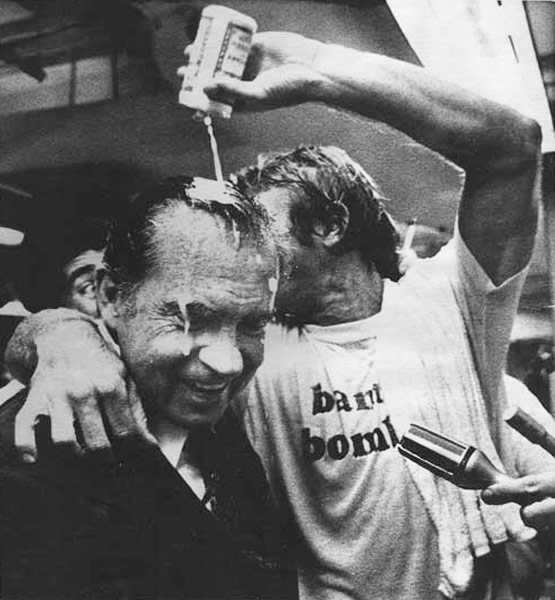

Neely’s group were not among them. Instead, they had set up a picnic site in a small park, offering a barbecue and leftist pamphlets. Someone had planted a bright red hammer-and-sickle flag in the grass. On a nearby table hung a black banner that bore the words “Redneck Revolt: anti-racist, pro-gun, pro-labor”.

“If you haven’t noticed, we aren’t liberals,” said Jeremy Beck, one of Neely’s cookout friends. “You know, if you keep going further left, eventually, you go left enough to get your guns back.”

Wooly liberals, they’re not. Redneck Revolt is a nationwide organization of armed political activists from rural, working-class backgrounds who strive to reclaim the term “redneck” and promote active anti-racism. It is not an exclusively white group, though it does take a special interest in the particular travails of the white poor. The organization’s principles are distinctly left-wing: against white supremacy, against capitalism and the nation-state, in support of the marginalized.

Pennsylvania is an open-carry state, where gun owners can legally carry firearms in public without concealment. Redneck Revolt members often see the practice of openly carrying a gun as a political statement: the presence of a visible weapon serves to intimidate opponents and affirm gun rights. Many of the cookout attendees owned guns, and had considered bringing them today – but ultimately they had decided to come unarmed, in the interest of keeping the event family-friendly.•

From “Under Siege by Liberals,” Lois Beckett’s Guardian reportage about a Nevada town with a name that sounds post-apocalyptic:

Nucla became nationally famous when it passed an ordinance requiring every household to own a gun five years ago – a move that is still wildly popular among residents. But past Nucla’s one minute of fame, locals worry about their beloved home becoming a ghost town.

In September, in the wake of a lawsuit from an environmental group, Nucla’s major employer, the local coal-fired power plant, announced that it would be shutting down in 2022. The coal mine that supplied the plant would be shutting down as well. In total, about 80 jobs were at risk – a huge number in a town whose population boasted, according to the 2010 census, only 711 people.

For locals, this decision was a death knell brought on by liberals who live in big cities. Nucla residents bristle at the warnings about the risk of exposure to radiation, and roll their eyes at A-listers like Darryl Hannah, the Hollywood actress known for Splash and Kill Bill, who joined the activism against the local uranium industry.

Liberals fighting against the mining industry are good at telling them no, residents say, but don’t present them with any alternatives – not ones that come with real salaries. Richard Craig, a former Nucla town board member, recalled a comment by a member of an environmental group saying during one of the contentious hearings: “Well, I don’t see why they don’t want to go live in the city.”

“It’s almost like – I hate using this word, it’s being used so often – it’s almost like a conspiracy: ‘We need to move everybody out of rural areas and go live in the cities and suburbs,’” Craig said.•