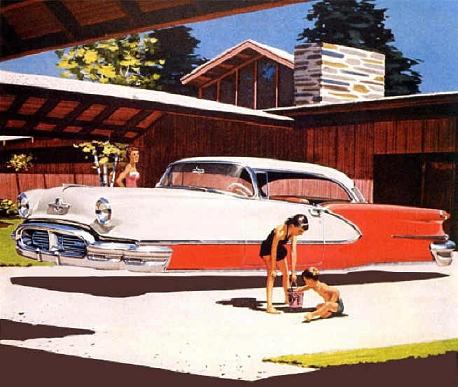

Remember when workers were being nickeled and dimed? Ah, the good old days.

Barbara Ehrenreich, who’s spent much of her journalistic career studying the indignities of the working class, has penned a New York Times review of Martin Ford’s excellent book, Rise of the Robots, an extended diagnosis and concise prescription for the potential mass automation of work. The machines, he argues, are coming for your job, whether your collar is white or blue.

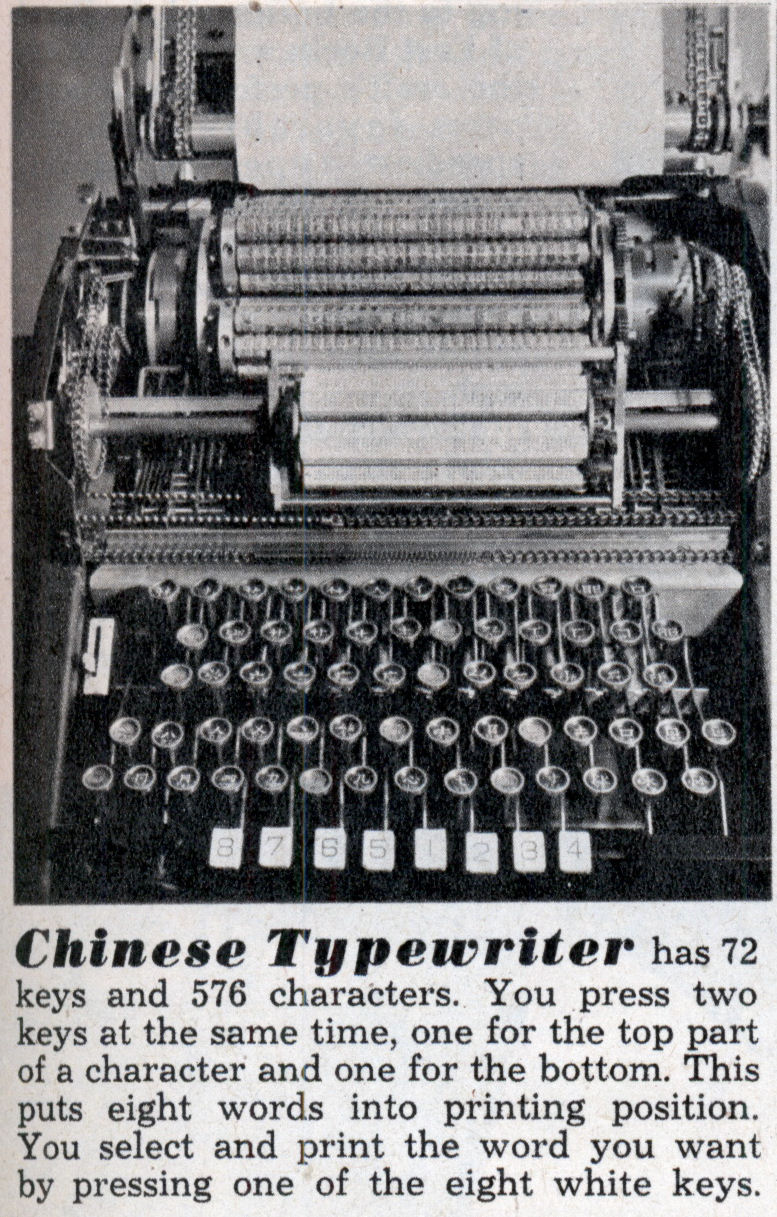

Ford is decidedly in the this-time-it’s-different camp who believe that unlike the the Industrial Revolution, which replaced farm jobs with better ones, this second machine age will not create new positions for people who have their careers disappeared. He also argues that the earlier fear of automation, a twenty-or-so-year period beginning in the late 1940s and cresting in the mid-1960s, wasn’t incorrect, just early.

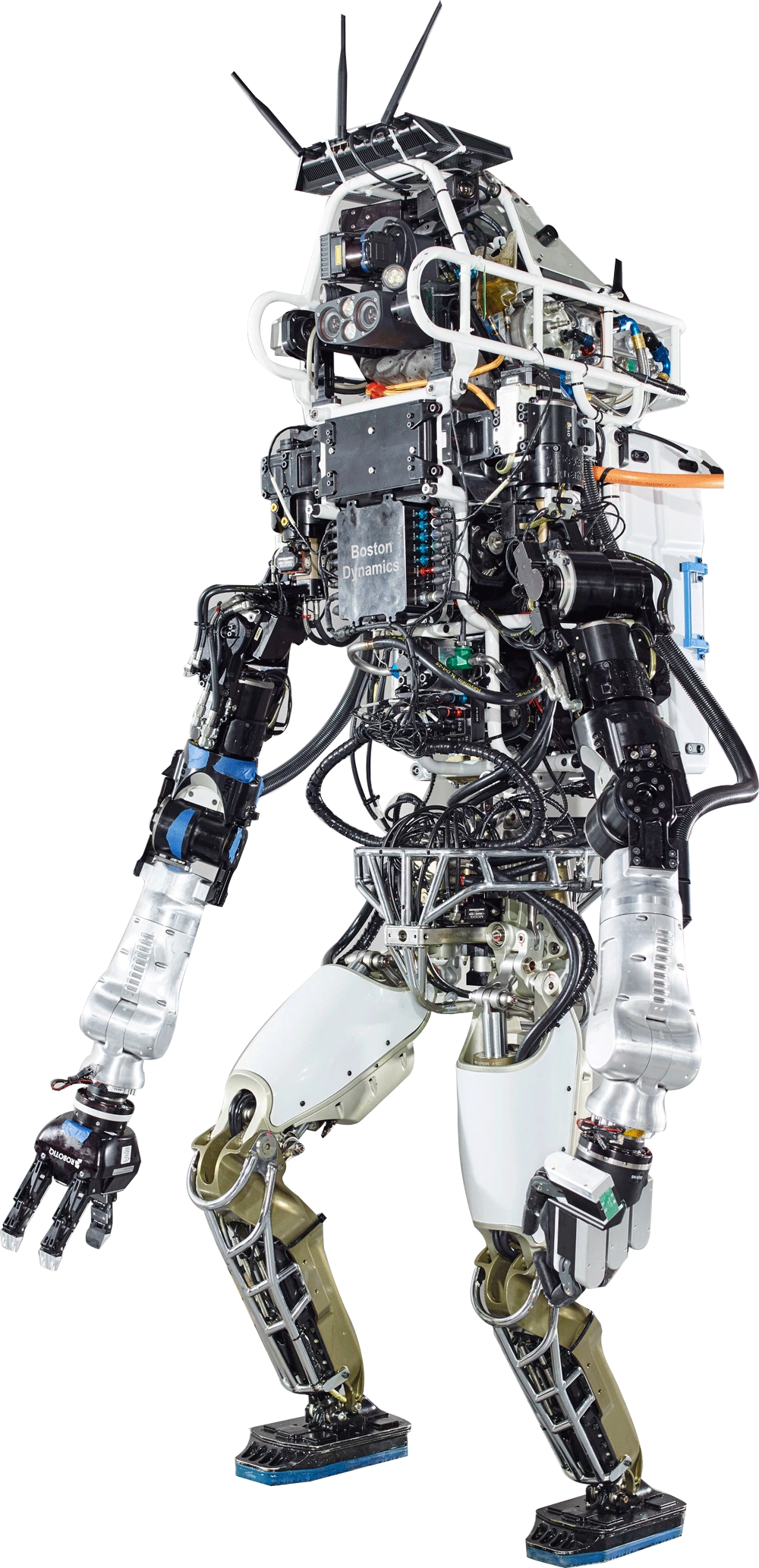

The author’s argument is supported by academic research of all manner, but it’s a compelling and lucid one deserving of a wide readership. While he addresses the longer term possibility of Strong AI, which would clearly make the situation even more pressing, Ford focuses mostly on the type of Weak AI (non-conscious machines) set to invade every industry from taxi to delivery to law to medicine. In fact, the first inroads have already been made, and they’ve been dazzling. If Moore’s Law holds out a little while longer, the march of the non-wooden soldiers will come at a brisk pace, and the idea of near-universal employment will become an impossibility. No nickels for you, no dimes. What then?

Despite the alarmist topic of the book, Ford is reasoned and cautious, conservative even. Like myself, he argues against the most-quoted Piketty approach to combating income inequality, education, as a panacea. A worthwhile thing, sure, but not a broad answer. Ford asserts that we’ll most likely need to opt for a guaranteed basic income (incentivized to promote work whenever possible) to be funded in part from shifting tax responsibilities from workers to capital. (His feelings on the need for basic income have been shared by disparate thinkers: Andrew McAfee, Charles Murray, Friedrich Hayek, Eric Brynjolfsson, etc.) Easier said than done considering our political climate, but if wealth and productivity increase in the next few decades while employment continually ticks down, Americans at some point will likely not be pacified by bread and Kardashians.

From Ehrenreich:

In the late 20th century, while the blue-collar working class gave way to the forces of globalization and automation, the educated elite looked on with benign condescension. Too bad for those people whose jobs were mindless enough to be taken over by third world teenagers or, more humiliatingly, machines. The solution, pretty much agreed upon across the political spectrum, was education. Americans had to become intellectually nimble enough to keep ahead of the job-destroying trends unleashed by technology, both robotization and the telecommunication systems that make outsourcing possible. Anyone who wanted a spot in the middle class would have to possess a college degree — as well as flexibility, creativity and a continually upgraded skill set.

But, as Martin Ford documents in Rise of the Robots, the job-eating maw of technology now threatens even the nimblest and most expensively educated. Lawyers, radiologists and software designers, among others, have seen their work evaporate to India or China. Tasks that would seem to require a distinctively human capacity for nuance are increasingly assigned to algorithms, like the ones currently being introduced to grade essays on college exams. Particularly terrifying to me, computer programs can now write clear, publishable articles, and, as Ford reports, Wired magazine quotes an expert’s prediction that within about a decade 90 percent of news articles will be computer-generated. …

This is both a humbling book and, in the best sense, a humble one. Ford, a software entrepreneur who both understands the technology and has made a thorough study of its economic consequences, never succumbs to the obvious temptation to overdramatize or exaggerate. In fact, he has little to say about one of the most ominous arenas for automation — the military, where not only are pilots being replaced by drones, but robots like the ones that now defuse bombs are being readied for deployment as infantry. Nor does Ford venture much into the spectacular possibilities being opened up by wearable medical devices, which can already monitor just about any kind of biometric data that can be collected in an I.C.U. Human health workers may eventually be cut out of the loop, as tiny devices to sense blood glucose levels, for example, learn how to signal other tiny implanted devices to release insulin.

But Rise of the Robots doesn’t need any more examples; the human consequences of robotization are already upon us, and skillfully chronicled here.•