My default position on whistleblowers is I don’t want them imprisoned, since it’s a more dangerous world without them. I feel that way about Edward Snowden, as sloppy as he might have been at times in his mission. I still wonder, however, if much will truly come of his daring.

In his New York Times Op-Ed piece, Snowden declares the world has said “no” to surveillance, but I’m not so sure. Spying has been with us for as long as there’s been information, and governments have always been involved, using the Cold War or the War on Terror or any other conflict as an excuse. And I truly wonder how any legislation is going to keep up with technology. That one isn’t really a fair race. Perhaps even more difficult to control than government will be huge corporations, which don’t even have to break the law–just offer us a Faustian bargain–to get at what’s inside our brains. The Internet of Things will make it very easy for everyone to be tracked at all times.

At Reddit, Mattathias Schwartz of the New Yorker conducted a predictably smart Ask Me Anything about Snowden. A few exchanges follow.

_________________________

Question:

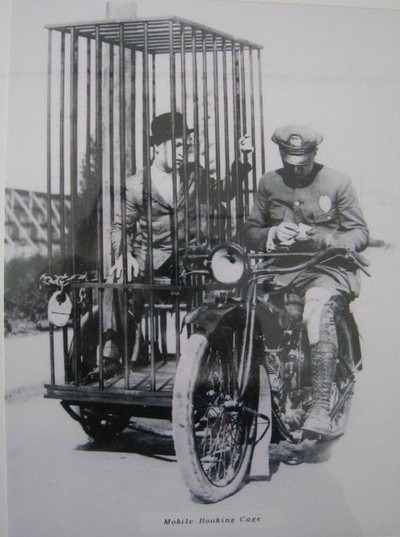

Why are whistleblowers treated like criminals?

Mattathias Schwartz:

Well, if whistleblowers come from within the US intelligence community (FBI, CIA, NSA, DEA, DIA, etc.) they usually are criminals, under current federal laws against the release of classified information. A lot of recent protections that apply to whistleblowers do not apply to those who work within the intelligence community. The Washington Post did a good story on this, and how it applies to Snowden’s case, here …http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/fact-checker/wp/2014/03/12/edward-snowdens-claim-that-as-a-contractor-he-had-no-proper-channels-for-protection-as-a-whistleblower/ … and my colleague Jane Mayer wrote about Thomas Drake, an NSA employee who attempted to blow the whistle, here …http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/05/23/the-secret-sharer.

_____________________

Question:

Can speculate why there seems to be such apathy (after an initial and momentary outrage at the water cooler) by the American public regarding the erosion of our civil liberties? Case in point would be the NSA spying and data collection efforts to which change has essentially squeaked by with little continued pressure by the constituents since the revelations.

Mattathias Schwartz:

I think it’s too soon to say whether there’s been a sea change or not. It’s all still in play. To see where it winds up, you’d have to track what happens with the PCLOB’s ongoing inquiry into Executive Order 12333, and you’d have to see whether the Supreme Court decides to weigh in on Fourth Amendment / NSA / surveillance issues. It already started to with United States v. Jones and if I had to guess, I would say that there will be more action to come on that front.

_____________________

Question:

Do you worry about the future of well-funded investigative journalism now that we’re living in the era of free internet news?

Mattathias Schwartz:

Yes! There is a lot to worry about here. Part of me thinks that Big Tech should be funding this stuff–they certainly make plenty of money on journalism that they don’t pay for!–but that’s a troubled notion if you look at how much money Big Tech spends to influence policy in Washington. Reporting is expensive and the number of institutions willing to put up the money to do it is shrinking–I am lucky to be working with the New Yorker, which is one of them. I can foresee three models under which this kind of work can continue. There’s the opera model, which depends on patronage and a small, influential, highbrow audience. There’s the model that the Swiss watch companies found after the invention of the Quartz watch, shifting away from mass-market utility and towards luxury, which isn’t so different from the opera model, actually. And then you’ve got the Snowden model, where a private individual takes it upon themselves to speak out in those places where they feel that investigative journalists, and politicians, have failed to do so. There will always be people who want this information, and over time, supply will keep pace with demand, especially when you can cram so much supply onto a USB stick.

_________________________

Question:

I thought the Snowden op-ed in the NYT today was a little strange, but can’t tell if it’s my own cynicism. Seemed like a politician’s intervention–lots of spin. What did you think?

Mattathias Schwartz:

Hi K, Yeah it is “spin” in the sense that he is obviously trying to influence the Beltway conversation, but I enjoyed the writing and I was glad to see ES speaking in his own voice finally, as opposed to speaking through his collaborators, or through documents. Looking at it from the outside, my sense is that he wants to come home. And I liked the bit about a “post-terror generation.”

_________________________

Question:

Do you think he’ll ever be able to come home without spending a long time in federal prison?

Mattathias Schwartz:

It’s hard to predict the future but I wouldn’t be surprised if there were a trial on some limited set of charges, which would give Snowden a public platform at the risk of a limited jail term, if he were found guilty. Snowden has already said that he’s willing to come home if he can be guaranteed a fair trial. And I can’t imagine that the US government would want a guy who knows so much staying in Russia for the long term.•

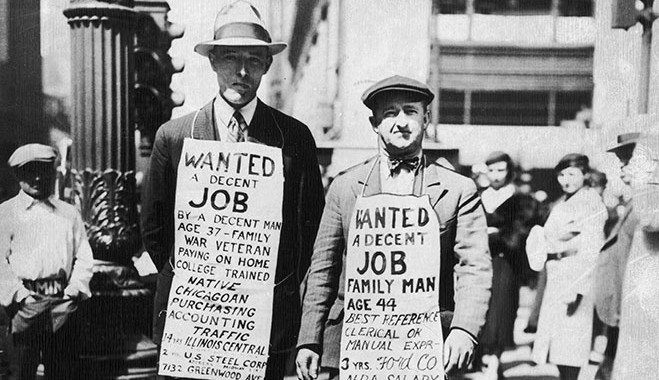

It’s not exactly the most pressing concern to sort out how we’d conduct justice should it become possible for humans to upload consciousness to computers and attain a sort-of immortality for our sort-of selves. But it may be theoretically possible and makes for a fun bull session, so Conor Friedersdorf penned a well-written

It’s not exactly the most pressing concern to sort out how we’d conduct justice should it become possible for humans to upload consciousness to computers and attain a sort-of immortality for our sort-of selves. But it may be theoretically possible and makes for a fun bull session, so Conor Friedersdorf penned a well-written