1) Another way high-skill workers may enter the labor market is through immigration, the total volume of which is limited by the number of visas granted, which is capped by legislation. Recent evidence shows that the contribution of skilled migration to innovation has been substantial. For example, Peri, Shih, and Sparber (2014) find that inflows of foreign science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) workers explain between 30 and 50 percent of the aggregate productivity growth that took place in the United States between 1990 and 2010. There is also abundant anecdotal evidence that the contribution of immigrants to innovation, entrepreneurship and education is substantial in the United States. Immigrants accounted for about one-quarter of U.S.-based Nobel Prize recipients between 1990 and 2000. Immigrants were also among the key founders for one-quarter of all U.S. technology and engineering companies started between 1995 and 2005 with at least 1 million dollars in sales in 2006 and for over half of such companies in Silicon Valley (Wadhwa et al. 2007). These authors also report that 24 percent of all patents originating from the United States are authored by non-citizens.

2) Private business accounts for virtually all of the recent growth in R&D. Nonprofit institutions like universities had a negligible impact on growth. The manufacturing sector is an important driver of R&D. In 2013 and 2014, manufacturing accounted for roughly 75 percent of R&D growth and non-manufacturing accounted for the other 25 percent (see Table 5-1). Two manufacturing sectors that have notably improved relative to the pre-crisis time period (2001–2007) are semiconductors and electronic components and motor vehicles and parts. In addition, manufacturing employs 60 percent of U.S. R&D employees and accounts for more than two thirds of total R&D volume in the United States. Manufacturing is also responsible for the vast majority of U.S. patents issued (Sperling 2013).

Federal R&D spending can be decomposed into defense and nondefense R&D spending, as displayed in Figure 5-7. Compared to most of the last decade, both defense and non-defense R&D funding have dropped slightly as a percentage of GDP in this decade. As a result of the one-time boost from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), Federal R&D funding approached 1.0 percent of GDP in fiscal years 2009-10; however, subsequent Congressional appropriations have failed to maintain these gains.

The decline in federally funded R&D is potentially consequential because Federal and industry R&D investments should be thought of as complements and not substitutes for each other. The Federal R&D portfolio is somewhat balanced between research and development, while industry R&D predominantly focuses on later-stage product development. Figure 5-8 shows that the Federal Government is the majority supporter of basic research—the so-called “seed corn” of future innovations and industries that generates the largest spillovers and thus is at risk of being the most underfunded in a private market—and, as such, the Administration’s efforts have prioritized increasing Federal investments in basic research while also pushing for an overall increase in Federal R&D investment.

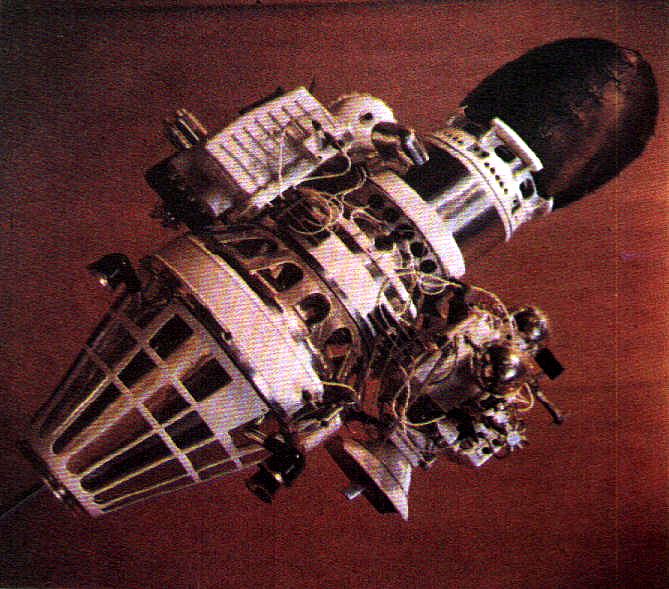

3) Robotics

One area of innovation that can help the United States to boost TFP growth in the future is robotics. The first U.S. robots were introduced into production by General Motors in 1961, and their prevalence has grown steadily over time, particularly in manufacturing and the auto industry (Gordon 2012). Recently, the deployment of robots has accelerated, leading them to contribute more to productivity, as described below. However, these changes potentially also create challenges in labor markets as concerns have arisen about the extent to which robots will displace workers from their jobs. An economy must carefully assess these developments to encourage innovation but also to provide adequate training and protections for workers.

The use of industrial robots can be thought of as a specific form of automation. As a characteristic of innovation for centuries, automation enhances production processes from flour to textiles to virtually every product in the market. Automation, including through the use of information technology, is widely believed to foster increased productivity growth 232 | Chapter 5 (Bloom, Sadun, and Van Reenen 2012). In many cases, mostly for higherskilled work, automation has resulted in substantial increases in living standards and leisure time. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) defines a robot to be an “actuated mechanism programmable in two or more axes with a degree of autonomy, moving within its environment, to perform intended tasks.”9 This degree of autonomy makes robotic automation somewhat different from historical examples of automation, such as the replacement of weavers with looms. Some of these machines can operate for extended periods of time without human control, presaging the rise of a potentially paradigm-shifting innovation in the productivity process.

Robots, like other types of automation, can be either complements to, or substitutes for, conventional labor. For example, at many of the country’s biggest container shipping ports—the primary gateways to and from the United States for waterborne international shipments—automation has replaced longshoremen in a variety of activities, from computerized cargo management platforms that allow for visualization of the loading of a container ship in real time to software that allows for end-to-end management of individual containers throughout the unloading process (Feuer 2012). By contrast, there are a number of “smart warehouse” applications that involve varying amounts of automation to complement the work done by warehouse fulfillment workers. Examples include LED lights on shelves that light up when a worker reaches the appropriate location and mobile robots that bring inventory from the floor to a central place for packaging (Field 2015; Garfield 2016). The latter example realigns employees away from product-retrieval tasks and focuses them instead on the inventory-sorting phase of the process, for which humans have a comparative advantage over machinery.

…

Effect of Robotics on Workers

While industrial robots have the potential to drive productivity growth in the United States, it is less clear how this growth will affect workers. One view is that robots will take substantial numbers of jobs away from humans, leaving them technologically unemployed—either in blissful leisure or, in many popular accounts, suffering from the lack of a job. Most economists consider either scenario unlikely because several centuries of innovation have shown that, even as machines have been able to increasingly do tasks humans used to do, this leads humans to have higher incomes, consume more, and creates jobs for almost everyone who wants them. In other words, as workers have historically been displaced by technological innovations, they have moved into new jobs, often requiring more complex tasks or greater levels of independent judgment.

A critical question, however, is the pace at which this happens and the labor market institutions facilitate the shifting of people to new jobs. As an extreme example, if a new innovation rendered one-half of the jobs in the economy obsolete next year, then the economy might be at full employment in the “long run.” But this long run could be decades away as workers are slowly retrained and as the current cohort of workers ages into retirement and is replaced by younger workers trained to find jobs amidst the new technological opportunities. If, however, these jobs were rendered obsolete over many decades then it is much less likely that it would result in largescale, “transitional” unemployment. Nevertheless, labor market institutions are critical here too, and the fact that the percentage of men ages 25-54 employed in the United States slowly but steadily declined since the 1950s, as manufacturing has shifted to services, suggests that challenges may arise.

Over time, economists expect wages to adjust to clear the labor market and workers to respond to incentives to develop human capital. Inequality could increase; indeed, most economists believe technological change is partially responsible for rising inequality in recent decades. Whether or not robots will increase or decrease inequality depends in part on the extent to which robots are complements to, or substitutes for, labor. If substitution dominates, then the question becomes whether or not labor has enough bargaining power such that it can share in productivity gains. At present, this question cannot be answered fully, largely because of limited research on the economic impact of robots. One of the few studies in this area finds that higher levels of robot density within an industry lead to higher wages in that industry (Graetz and Michaels 2015), suggesting that robots are complements to labor. The higher wages, however, might be due in part to robots’ replacing lower-skill workers in that industry, thus biasing wage estimates upwards.

The older literature on automation may give some clues about how robots will affect jobs in the future. This broader literature finds that, while there is some substitution of automation for human labor, complementary jobs are often created and new work roles emerge to develop and maintain the new technology (Autor 2015). One issue is whether these new jobs are created fast enough to replace the lost jobs. Keynes (1930) appears to have been concerned about the prospect for what he termed “technological unemployment,” borne out of the notion that societies are able to improve labor efficiency more quickly than they are able to find new uses for labor.

There has been some debate about which types of workers are most affected by automation. That is, jobs are not necessarily destroyed by automation but instead are reallocated. Autor and Dorn (2013) argue that so-called middle-skill jobs are what get displaced by automation and robots. These jobs, which have historically included bookkeepers, clerks, and certain assembly-line workers, are relatively easy to routinize. This results in middle-skill workers who cannot easily acquire training for a higher-skilled job settling for a position that requires a lower-skill level, which may then translate into lower wages. In contrast, high-skill jobs that use problemsolving capabilities, intuition and creativity, and low-skill jobs that require situational adaptability and in-person interactions, are less easy to routinize. Autor, Levy, and Murnane (2003) point out that robots and computerization have historically not been able to replicate or automate these tasks, which has led to labor market polarization. While not specifically tied to automation, Goos, Manning, and Salomons (2014) find broad evidence of this labor market polarization across European countries.

In contrast, recent papers by Autor (2015) and Schmitt, Shierholz, and Mishel (2013) suggests that the labor market polarization seen in the 1980s and 1990s may be declining. Data from the 2000s suggests that lower- and middle-skill workers have experienced less employment and wage growth than higher-skilled workers. Frey and Osborne (2013) argue that big data and machine learning will make it possible to automate many tasks that were difficult to automate in the past. In a study specifically on robots and jobs, Graetz and Michaels (2015) find some evidence that higher levels of robot density within an industry lead to fewer hours worked by low-skilled workers in that industry.

While robotics is likely to affect industrial sectors of the economy differently, it also is likely to affect occupations within these sectors differently. Two recent studies have used data on occupational characteristics to study how automation might differentially affect wages across occupations (Frey and Osborne 2013; McKinsey Global Institute 2015). Both studies rely on the detailed occupational descriptions from O*NET, an occupational data source funded by the U.S. Department of Labor, to derive probabilities that an occupation will be automated into obsolescence. While the two studies have slightly different categorizations, they both find a negative relationship between wages and the threat of automation.•