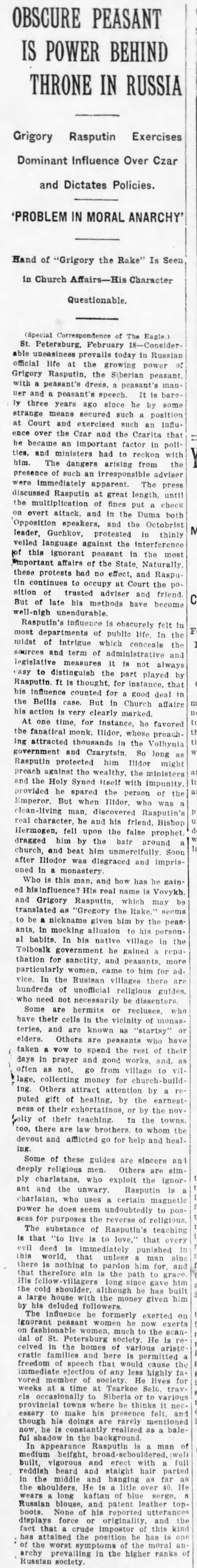

In this time of potential totalitarianism, two very different journalists, former Dubya speechwriter David Frum and veteran Putin chronicler Masha Gessen, have done the most outstanding work, warning of the gathering threat to American liberal democracy. Each has a new piece on the topic.

In “How to Build an Autocracy,” an Atlantic cover story, Frum writes speculatively about how the U.S., over the next four years, could be pulled from its foundations, despite a system that supposedly safeguards us from such affronts.

“Checks and balances is a metaphor, not a mechanism,” offers Frum, asserting that our system is only as good as those who serve it at any given moment. We depend on Americans of good faith to combat a Berlusconi angling to become a Mussolini, and while many such citizens exist in the country, they will be far from levers of power. The Administration will only appoint and tolerate conspirators. Anyone who defies will be dismissed.

The Senate and the Congress could prevent our fall from decency, but if Mitch McConnell was guided by the Constitution, Merrick Garland would have received a fair chance, and if Paul Ryan was committed to democracy, hearings about James Comey’s outrageous pre-election actions would be foremost on his mind. They will not save us. Only we can. That’s complicated, since millions of Americans seem to not notice the danger, maybe even wouldn’t mind a dictatorship if it supported their politics or proved financially profitable.

Former Nixon lawyer John Dean says the Trump Presidency “will end in calamity.” I think, horribly enough, that’s true whether liberty wins or not.

In “The Styrofoam Presidency,” Gessen’s New York Review of Books essay, the writer explains how kakistocracy (government by the least qualified or most unprincipled) has taken hold in America. I’ve written previously that this election seemed to me propelled by, among other factors, a “large-scale revenge of mediocrity, of people wanting to establish an order where might, not merit, will rule.”

It’s hard to argue that is not what now will oversee us on a day when Jerry Falwell Jr. revealed he’s to lead a Federal Task Force on Higher Education policy. If Liberty University is to be the template for the American college, the “genius” Peter Thiel may have to wait quite awhile longer for his flying cars.

From Frum:

Trump-critical media do continue to find elite audiences. Their investigations still win Pulitzer Prizes; their reporters accept invitations to anxious conferences about corruption, digital-journalism standards, the end of Nato, and the rise of populist authoritarianism. Yet somehow all of this earnest effort feels less and less relevant to American politics. President Trump communicates with the people directly via his Twitter account, ushering his supporters toward favorable information at Fox News or Breitbart.

Despite the hand-wringing, the country has in many ways changed much less than some feared or hoped four years ago. Ambitious Republican plans notwithstanding, the American social-welfare system, as most people encounter it, has remained largely intact during Trump’s first term. The predicted wave of mass deportations of illegal immigrants never materialized. A large illegal workforce remains in the country, with the tacit understanding that so long as these immigrants avoid politics, keeping their heads down and their mouths shut, nobody will look very hard for them.

African Americans, young people, and the recently naturalized encounter increasing difficulties casting a vote in most states. But for all the talk of the rollback of rights, corporate America still seeks diversity in employment. Same-sex marriage remains the law of the land. Americans are no more and no less likely to say “Merry Christmas” than they were before Trump took office.

People crack jokes about Trump’s National Security Agency listening in on them. They cannot deeply mean it; after all, there’s no less sexting in America today than four years ago. Still, with all the hacks and leaks happening these days—particularly to the politically outspoken—it’s just common sense to be careful what you say in an email or on the phone. When has politics not been a dirty business? When have the rich and powerful not mostly gotten their way? The smart thing to do is tune out the political yammer, mind your own business, enjoy a relatively prosperous time, and leave the questions to the troublemakers.•

From Gessen:

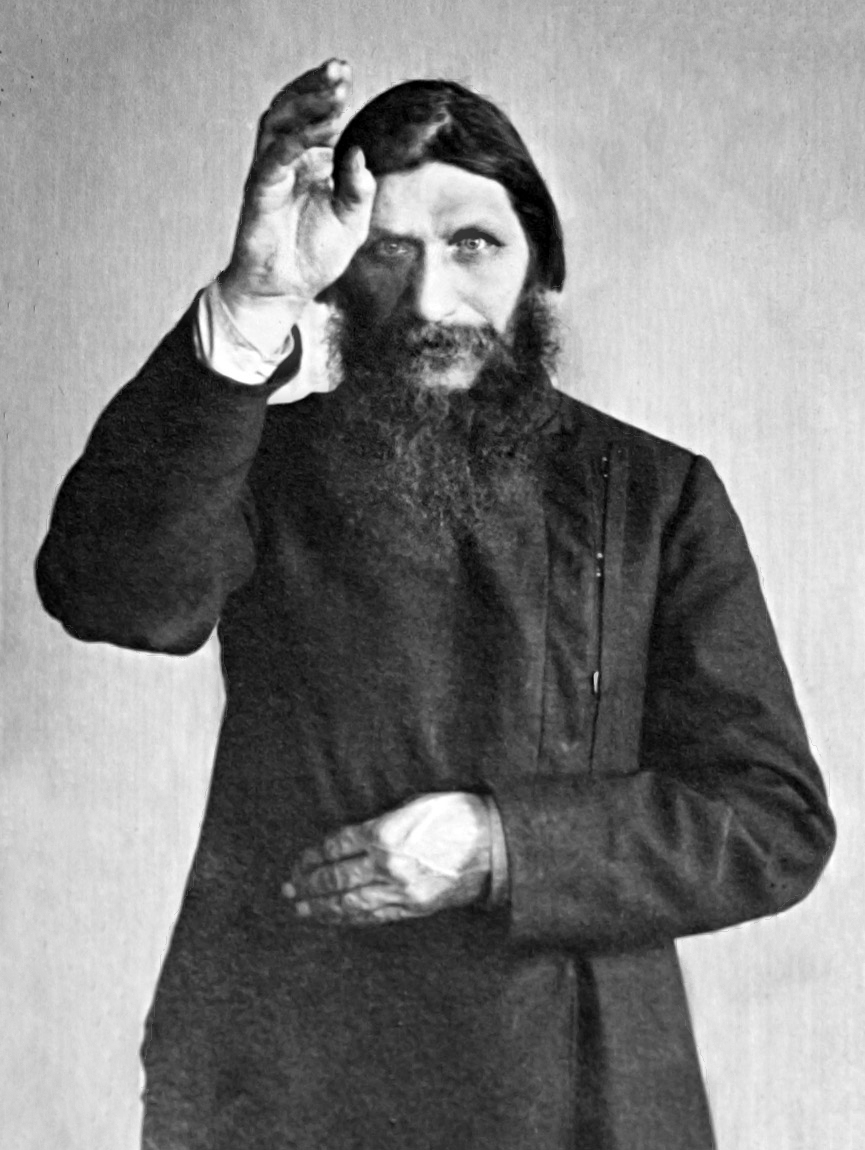

The rule of the worst seemed to become a thing of the past in the 1990s, but under Putin mediocrity returned with a vengeance. Not only did the media come under the control of the Kremlin but it acquired an amateurish quality. Not only did the government start lying, but did so in dull, simple, and unimaginative language. Putin’s government is filled with people who plagiarized their dissertations—as did Putin himself. The ministers are subliterate. The minister of culture, who has a doctorate in history, regularly exposes his ignorance of history; indeed, Trump might be tempted to plagiarize the minister’s dissertation, which begins with the assertion that the criterion of truth in history is determined solely by the national interests of Russia—if it’s good for the country, it must be true (much of the rest of the dissertation is itself plagiarized). Other ministers provide the differently minded Russian blogosphere with endless hours of fun because they use words the meaning of which they clearly don’t know, or ones that don’t exist—as when a newly chosen education minister invented a word that seemed to mean that she had been appointed to the cabinet by God. They also make ignorant, repressive, inhumane policy. But their daily subversion of integrity and principle is indeed aesthetic in nature. And it serves a purpose: by degrading language and discrediting the spectacle of politics the Russian government is destroying the public sphere.

Sometimes vastly different processes yield surprisingly similar results. Trump is staging an assault on America’s senses that feels familiar to me—not because he admires Putin (though he does) or because he is Putin’s puppet, but because they seem to be genuinely kindred spirits. It might take a long time to understand why we have come to enter the age of a kakistocracy, but evidently we have.•