From the October 4, 1938 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

Ideas and technology and politics and journalism and history and humor and some other stuff.

You are currently browsing the archive for the Politics category.

Tags: Arturo Toscanini

Much has been made of the Trump campaign overwhelmingly winning America’s rural counties ravaged by opioid abuse, the narrative being that economic hardship begat drug addiction which in turn led lost souls into the arms of an American Mussolini.

Inconvenient truths intrude, however.

Not all of these small towns are doing badly economically, and some are thriving, having rebounded remarkably since the Great Recession. Nor did the drug abuse begin with a wayward scrip meant to soothe back pain.

One illuminating example can be found in Jack Healy’s New York Times article about the Winemiller farming family in Ohio’s Clermont County, which boasts a low 4.1% unemployment rate, who have already lost two of three adult children to heroin overdoses, with the third one battling to beat the same poison. The younger members of the clan began using alcohol and narcotics when they were teens, years before an Obama Presidency or the sharp financial downturn of 2008, eventually graduating to the drug that would undo their home.

The paterfamilias, who has suffered greatly, voted Republican in the recent Presidential election. “My view on Donald Trump, he’s what this country needed years ago: someone that’s hard-core,” he tells the Times. The woebegone man wants someone to arrest reality, to force sense on a chaotic situation, to slap handcuffs on these strange demons.

But the problem starts with our own demons, and we’re not going to be able to bluster and batter them out of existence. We have to go deeper inside and further back to get to the root of the problem. To figure things out, we need to look in the mirror rather than to a monster.

An excerpt:

The Winemillers live on the eastern edge of Clermont County, about an hour east of Cincinnati, where a suburban quilt of bedroom towns, office parks and small industry thins into woods and farmland, mostly for corn and soybeans. Apple orchards and pumpkin farms — now closed for the season — are tucked among clusters of small churches, small businesses and even smaller ranch-style brick houses. Every so often, the roads wind past the gates of a big new mansion or high-end subdivision being built in the woods.

Jobs have returned to the area since the recession, and manufacturing businesses are popping up along the freeway that circles Cincinnati. The county’s unemployment rate is only 4.1 percent, and every morning, the city-bound lanes of skinny country roads are packed with people heading to work.

But the economic resilience has done little to insulate the area from a cascade of cheap heroin and synthetic opiates like fentanyl and carfentanil, an elephant tranquilizer, which have sent overdose rates soaring across much of the country, but especially in rural areas like this one.

Drug overdoses here have nearly tripled since 1999, and the state as a whole has been ravaged. In Ohio, 2,106 people died of opioid overdoses in 2014, more than in any other state, according to an analysis of the most recent federal data by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

In rural Wayne Township, where the Winemillers and about 4,900 other people live, the local fire department answered 18 overdose calls last year. Firefighters answered three in one week this winter, and said the spikes and lulls in their overdose calls gave them a feel for when particularly noxious batches of drugs were brought out to the countryside from Cincinnati or Dayton.

They get overdose calls for people living inside the Edenton Rural School, a shuttered brick schoolhouse where officers have cleared away signs of meth production and found the flotsam of drug use on the floors.

“I don’t think we’re winning the battle,” said David Moulden, the fire chief. “It gives you a hopelessness.”•

Tags: Jack Healy

Thomas E. Ricks of Foreign Policy asked one of the most horrifying questions about America you can pose: Will we have another civil war in the next ten to fifteen years? Keith Mines of the United States Institute of Peace and a career foreign service officer provided a sobering reply, estimating the chance for large-scale internecine violence at 60%.

Things can change unexpectedly, sometimes for the better, but it sure does feel like we’re headed down a road to ruin, with the anti-democratic, incompetent Trump and company provoking us to a tipping point. The Simon Cowell-ish strongman may seem a fluke because of his sizable loss in the popular vote, but in many ways his political ascent is the culmination of the past four decades of dubious U.S. cultural, civic, economic, technological and political decisions. We’re not here by accident.

· · ·

One of the criteria on which Mines bases his diagnosis: “Press and information flow is more and more deliberately divisive, and its increasingly easy to put out bad info and incitement.” That triggered in me a memory of a 2012 internal Facebook study, which, unsurprisingly, found that Facebook was an enemy of the echo chamber rather than one of its chief enablers. I’m not saying the scholars involved were purposely deceitful, but I don’t think even Mark Zuckerberg would stand by those results five years later. We’re worlds apart in America, and social media, and the widespread decentralization of all media, has hastened and heightened those divisions.

· · ·

An excerpt from Farhad Manjoo’s 2012 Slate piece “The End of the Echo Chamber,” about the supposed salubrious effects of social networks, is followed by Mines’ opening.

From Manjoo:

Today, Facebook is publishing a study that disproves some hoary conventional wisdom about the Web. According to this new research, the online echo chamber doesn’t exist.

This is of particular interest to me. In 2008, I wrote True Enough, a book that argued that digital technology is splitting society into discrete, ideologically like-minded tribes that read, watch, or listen only to news that confirms their own beliefs. I’m not the only one who’s worried about this. Eli Pariser, the former executive director of MoveOn.org, argued in his recent book The Filter Bubble that Web personalization algorithms like Facebook’s News Feed force us to consume a dangerously narrow range of news. The echo chamber was also central to Cass Sunstein’s thesis, in his book Republic.com, that the Web may be incompatible with democracy itself. If we’re all just echoing our friends’ ideas about the world, is society doomed to become ever more polarized and solipsistic?It turns out we’re not doomed. The new Facebook study is one of the largest and most rigorous investigations into how people receive and react to news. It was led by Eytan Bakshy, who began the work in 2010 when he was finishing his Ph.D. in information studies at the University of Michigan. He is now a researcher on Facebook’s data team, which conducts academic-type studies into how users behave on the teeming network.

Bakshy’s study involves a simple experiment. Normally, when one of your friends shares a link on Facebook, the site uses an algorithm known as EdgeRank to determine whether or not the link is displayed in your feed. In Bakshy’s experiment, conducted over seven weeks in the late summer of 2010, a small fraction of such shared links were randomly censored—that is, if a friend shared a link that EdgeRank determined you should see, it was sometimes not displayed in your feed. Randomly blocking links allowed Bakshy to create two different populations on Facebook. In one group, someone would see a link posted by a friend and decide to either share or ignore it. People in the second group would not receive the link—but if they’d seen it somewhere else beyond Facebook, these people might decide to share that same link of their own accord.By comparing the two groups, Bakshy could answer some important questions about how we navigate news online. Are people more likely to share information because their friends pass it along? And if we are more likely to share stories we see others post, what kinds of friends get us to reshare more often—close friends, or people we don’t interact with very often? Finally, the experiment allowed Bakshy to see how “novel information”—that is, information that you wouldn’t have shared if you hadn’t seen it on Facebook—travels through the network. This is important to our understanding of echo chambers. If an algorithm like EdgeRank favors information that you’d have seen anyway, it would make Facebook an echo chamber of your own beliefs. But if EdgeRank pushes novel information through the network, Facebook becomes a beneficial source of news rather than just a reflection of your own small world.

That’s exactly what Bakshy found. His paper is heavy on math and network theory, but here’s a short summary of his results. First, he found that the closer you are with a friend on Facebook—the more times you comment on one another’s posts, the more times you appear in photos together, etc.—the greater your likelihood of sharing that person’s links. At first blush, that sounds like a confirmation of the echo chamber: We’re more likely to echo our closest friends.

But here’s Bakshy’s most crucial finding: Although we’re more likely to share information from our close friends, we still share stuff from our weak ties—and the links from those weak ties are the most novel links on the network. Those links from our weak ties, that is, are most likely to point to information that you would not have shared if you hadn’t seen it on Facebook.•

From Mines:

What a great but disturbing question (the fact that you can even ask it). Weird question for me as for most of my career I have been traveling the world observing other countries in various states of dysfunction and answering this same question. In this case if the standard is largescale violence that requires the National Guard to deal with in the timeline you lay out, I would say about 60 percent.

I base that on the following factors:

— Entrenched national polarization of our citizenry with no obvious meeting place. (Not true locally, however, which could be our salvation; but the national issues are pretty fierce and will only get worse).

— Press and information flow is more and more deliberately divisive, and its increasingly easy to put out bad info and incitement.

— Violence is “in” as a method to solve disputes and get one’s way. The president modeled violence as a way to advance politically and validated bullying during and after the campaign. Judging from recent events the left is now fully on board with this, although it has been going on for several years with them as well — consider the university events where professors or speakers are shouted down and harassed, the physically aggressive anti-Israeli events, and the anarchists during globalization events. It is like 1859, everyone is mad about something and everyone has a gun.

— Weak institutions — press and judiciary, that are being further weakened. (Still fairly strong and many of my colleagues believe they will survive, but you can do a lot of damage in four years, and your timeline gives them even more time).

— Total sellout of the Republican leadership, validating and in some cases supporting all of the above.•

Tags: Keith Mines, Thomas E. Ricks

What should we do if the President is a demagogue, a fascist, and a vicious bigot who surrounds himself with more of the same? What if he tramples on the Constitution, slanders other public figures and makes up bullshit incessantly? What about if it’s becoming increasingly clear that his campaign colluded with the Kremlin to corrupt our election process? What if he’s using his office to greatly enrich himself and his family? What if he’s trying to delegitimize the free press and the judiciary branch so that he won’t have any checks on his worst impulses? What if he’s already committed several impeachable acts and nothing has happened?

What then?

In a Medium essay, Bernie Sanders asks “What Should We Do If the President Is a Liar?” The piece was written in response to ridiculous charges made by Amber Phillips of the Washington Post, who derided the Vermont Senator for “lowering the state of our political discourse” by pointing out that the President frequently lies, which he does.

This kind of knuckle-rapping is exactly what a Berlusconi who dreams of being a Mussolini depends on–it’s what all fascists rely upon. They behave as disgracefully as possible, accepting no basic rules or laws, while decent people are pinioned by polite norms, too afraid to say what’s blindingly apparent. Her comparison of Sanders’ rebuke to Rep. Joe Wilson yelling “you lie!” during an Obama State of the Union address is foolishly disingenuous and false moral equivalency of the highest order for many reasons, the biggest one being Obama wasn’t a serial liar and conspiracy-theory peddler while Trump is. Phillips’ description of Trump’s assertion of widespread voter fraud, which is a complete lie, as an “eyebrow-raising claim,” is one way to put it, just not the honest way.

· · ·

You know what would be good? If the Twitter brain trust announced they were revoking Trump’s account because he slandered President Obama with serious, baseless claims of wiretapping. They could point out that no one has an absolute right to tweet, that it’s a privilege. It’s a very, very easy privilege to earn, but there have to be some rules. If Trump can produce proof his tweets weren’t slanders, he can have his account reactivated. Until then, farewell.

· · ·

In “How Trump Became an Accidental Totalitarian,” Nick Bilton’s smart Vanity Fair “Hive” piece, the writer theorizes the new President’s outrageous and unhinged behavior isn’t the product of a Machiavellian mastermind but the acts of an unintelligent person who “doesn’t know what the hell he’s doing in the White House.” The opening:

Like everyone else, I’ve been thinking a lot of late about Donald Trump and his infamous Twitter meltdowns—trying to deduce exactly what he’s up to regarding his constant, and seemingly never-ending, attacks on the press. The more that Trump has pushed the narrative that all unfavorable reportage of his regime is “fake news,” the more I’ve noticed a leitmotif. Trump, it seems, is using Twitter the way despotic politicians have manipulated the media throughout the past century when they needed a comfortable vessel for their lies.

Just travel back to Weimar Germany, where during his ascent to power in 1920, Adolf Hitler purchased outright a newspaper called The Volkischer Beobachter, which would grow its circulation to more than 1 million readers in the 40s as it became the organ of the National Socialist regime. The Beobachter, as it was often called, facilitated the Nazis’ revolting propaganda and culture of genocidal hatred. It allowed Hitler and Goebbels the opportunity to publish countless fake news stories about adversarial countries, about Jews, and, indeed, the press.

In some ways, Hitler set an early precedent for how to propagate fake news (or call real news “fake”) at the dawn of the information age. Kim Jong Il would control state media to his advantage much the same way. Saddam Hussein and his sons “owned” a dozen newspapers in Iraq, controlling virtually everything that was printed, and what was not. Vladimir Putinmanipulates the press in Russia. (He also allegedly has journalists killed.)

Freedom of the press is a sacrosanct right of Western democracies. But Trump, who has upended so much of what we believe in, has proved that the First Amendment is no longer enough to keep honest reporting unmolested. Indeed, were Hitler or Saddam to operate in our modern times, God forbid, they wouldn’t need to go through the hassle of running a state organ or Beobachter news outlet. They could simply open up their smartphones, sign up for a Twitter account, and start tweeting lies 140 characters at a time, both pushing their own agenda and decrying as false anything that they disagreed with.•

Tags: Amber Phillips, Bernie Sanders, Donald Trump, Nick Bilton

When it comes to technology, promises often sound like threats.

In a very smart Edge piece, Chris Anderson, the former Wired EIC who’s now CEO of 3DRobotics, holds forth on closed-loop systems, which allow for processes to be monitored, measured and corrected–even self-corrected. As every object becomes “smart,” they can collect information about themselves, their users and their surroundings. In many ways, these feedback loops will be a boon, allowing (potentially) for smoother maintenance, a better use of resources and a cleaner environment. But the new arrangement won’t all be good.

The question Anderson posed which I used as the headline makes it sound like we’ll be able to control where such technology snakes, but I don’t think that’s true. It won’t get out of hand in a sci-fi thriller sense but in very quiet, almost imperceptible ways. There will hardly be a hum.

At any rate, Anderson’s story of how he built a drone company from scratch, first with the help of his children and then a 19-year-old kid with no college background from Tijuana, is amazing and a great lesson in globalized economics.

From Edge:

If we could measure the world, how would we manage it differently? This is a question we’ve been asking ourselves in the digital realm since the birth of the Internet. Our digital lives—clicks, histories, and cookies—can now be measured beautifully. The feedback loop is complete; it’s called closing the loop. As you know, we can only manage what we can measure. We’re now measuring on-screen activity beautifully, but most of the world is not on screens.

As we get better and better at measuring the world—wearables, Internet of Things, cars, satellites, drones, sensors—we are going to be able to close the loop in industry, agriculture, and the environment. We’re going to start to find out what the consequences of our actions are and, presumably, we’ll take smarter actions as a result. This journey with the Internet that we started more than twenty years ago is now extending to the physical world. Every industry is going to have to ask the same questions: What do we want to measure? What do we do with that data? How can we manage things differently once we have that data? This notion of closing the loop everywhere is perhaps the biggest endeavor of our age.

Closing the loop is a phrase used in robotics. Open-loop systems are when you take an action and you can’t measure the results—there’s no feedback. Closed-loop systems are when you take an action, you measure the results, and you change your action accordingly. Systems with closed loops have feedback loops; they self-adjust and quickly stabilize in optimal conditions. Systems with open loops overshoot; they miss it entirely. …

I use the phrase closing the loop because that’s the phrase we use in robotics. Other people might use the phrase big data. Before they called it big data, they called it data mining. Remember that? That was nuts. Anyway, we’re going to come up with a new word for it.

It goes both ways: The tendrils of the Internet reach out through sensors, and then these sensors feed back to the Internet. The sensors get smarter because they’re connected to the Internet, and the Internet gets smarter because it’s connected to the sensors. This feedback loop extends beyond the industry that’s feeding back to the meta-industry, which is the Internet and the planet.•

Tags: Chris Anderson

In the latest round of what may be gamesmanship between the American Intelligence Community and Russia, Wikileaks released information about purported CIA spying techniques, which included, among other tricks of the trade, a way to remotely hack smart televisions so that the watchers would become the watched. Such methods should surprise no one.

What does startle me is how receptive Americans are to being watched, as if in this decentralized media age, we’ve accepted, finally and completely, that all the world actually is a stage. It goes far beyond the way we revel in the modern freak show of Reality TV or allow social networks access to our private lives in return for a cheap platform on which to peddle our personalities. As sensors and microchips proliferate, we’re gradually turning every object into a computer from which we can be monitored and quantified. Big Brother will eventually have several siblings in every room. The shock is that we’re so willing to be members of this non-traditional family.

Chance the Gardner was all of us when he said, “I like to watch.” Apparently, we also like to be watched.

The opening of Sapna Maheshwari’s smart New York Times piece on the topic:

While Ellen Milz and her family were watching the Olympics last summer, their TV was watching them.

Ms. Milz, 48, who lives with her husband and three children in Chicago, had agreed to be a panelist for a company called TVision Insights, which monitored her viewing habits — and whether her eyes flicked down to her phone during the commercials, whether she was smiling or frowning — through a device on top of her TV.

“The marketing company said, ‘We’re going to ask you to put this device in your home, connect it to your TV and they’re going to watch you for the Olympics to see how you like it, what sports, your expression, who’s around,’” she said. “And I said, ‘Whatever, I have nothing to hide.’”

Ms. Milz acknowledged that she had initially found the idea odd, but that those qualms had quickly faded.

“It’s out of sight, out of mind,” she said, comparing it to the Nest security cameras in her home. She said she had initially received $60 for participating and an additional $230 after four to six months.

TVision — which has worked with the Weather Channel, NBC and the Disney ABC Television Group — is one of several companies that have entered living rooms in recent years, emerging with new, granular ways for marketers to understand how people are watching television and, in particular, commercials. The appeal of this information has soared as Americans rapidly change their viewing habits, streaming an increasing number of shows weeks or months after they first air, on devices as varied as smartphones, laptops and Roku boxes, not to mention TVs.

Through the installation of a Microsoft Kinect device, normally used for Xbox video games, on top of participants’ TVs, TVision tracks the movement of people’s eyes in relation to the television. The device’s sensors can record minute shifts for all the people in the room.•

Tags: Sapna Maheshwari

Masha Gessen has made it clear she doesn’t believe Russia is responsible for America electing an autocratic sociopath, and in the big picture she’s right.

I don’t doubt Kremlin interference one bit, nor that it was likely committed in concert with high-ranking members of the Trump campaign if not the President himself, but there’s no real excuse for nearly 63 million citizens voting for a candidate who was clearly a habitual liar, vicious demagogue and utter incompetent. That’s on us.

That’s not to say that we shouldn’t aggressively strive for the truth in this gravely serious matter, and that arrests shouldn’t be made and impeachment be pursued if illegal activities can be proven. Certainly Congress would be investigating the matter at full throttle if a Democratic President had behaved in a similar manner, but partisan hackery has become a hallmark of the legislative branch.

In a Gessen piece just published at the New York Review of Books, the reporter wonders why the Russian espionage is a more important lie to many in the media and the Intelligence Community than the avalanche of dishonesty Trump and his cabinet regularly send down the mountain. On this point, I’ll disagree with her.

She’s right that it would be foolish to focus on the Putin connection to the exclusion of the many other assaults on liberal governance we’re enduring nearly daily, but an American President conspiring with an adversarial foreign power to gain office–whether the machinations actually helped him win votes or not–would be a singular shock to the system. Destroying health care and lowering taxes on the highest earners would be awful policy, but it wouldn’t be treason. The suspicious activity proceeding the election may very well be.

From Gessen:

The dream fueling the Russia frenzy is that it will eventually create a dark enough cloud of suspicion around Trump that Congress will find the will and the grounds to impeach him. If that happens, it will have resulted largely from a media campaign orchestrated by members of the intelligence community—setting a dangerous political precedent that will have corrupted the public sphere and promoted paranoia. And that is the best-case outcome.

More likely, the Russia allegations will not bring down Trump. He may sacrifice more of his people, as he sacrificed Flynn, as further leaks discredit them. Various investigations may drag on for months, drowning out other, far more urgent issues. In the end, Congressional Republicans will likely conclude that their constituents don’t care enough about Trump’s Russian ties to warrant trying to impeach the Republican president. Meanwhile, while Russia continues to dominate the front pages, Trump will continue waging war on immigrants, cutting funding for everything that’s not the military, assembling his cabinet of deplorables—with six Democrats voting to confirm Ben Carson for Housing, for example, and ten to confirm Rick Perry for Energy. According to the Trump plan, each of these seems intent on destroying the agency he or she is chosen to run—to carry out what Steve Bannon calls the “deconstruction of the administrative state.” As for Sessions, in his first speech as attorney general he promised to cut back civil rights enforcement and he has already abandoned a Justice Department case against a discriminatory Texas voter ID law. But it was his Russia lie that grabbed the big headlines.

The unrelenting focus on Russia has yielded an unexpected positive result, however. Following Flynn’s resignation, Trump designated Lieutenant General H.R. McMaster, a thoughtful and highly respected military strategist, as his national security adviser. And Fiona Hill, probably the most knowledgeable American scholar of Putin’s Russia, is expected to take charge of Russia policy at the National Security Council. Hill has been a consistent and perceptive critic of Putin, and a proponent of maintaining sanctions imposed by the United States following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Both of these appointments—and the fact that sanctions remain in place six weeks into Trump’s fast-moving presidency—contradict the “Putin’s puppet” narrative (as does the fact that Russian domestic propaganda has already turned against Trump). But such is the nature of conspiracy thinking that facts can do nothing to change it.

Imagine if the same kind of attention could be trained and sustained on other issues—like it has been on the Muslim travel ban. It would not get rid of Trump, but it might mitigate the damage he is causing. Trump is doing nothing less than destroying American democratic institutions and principles by turning the presidency into a profit-making machine for his family, by poisoning political culture with hateful, mendacious, and subliterate rhetoric, by undermining the public sphere with attacks on the press and protesters, and by beginning the real work of dismantling every part of the federal government that exists for any purpose other than waging war. Russiagate is helping him—both by distracting from real, documentable, and documented issues, and by promoting a xenophobic conspiracy theory in the cause of removing a xenophobic conspiracy theorist from office.•

Tags: Donald Trump, Masha Gessen

Margaret Atwood is in an odd position: As our politics get worse, her stature grows. Right now, sadly (for us), she’s never towered higher.

Appropriate that on International Women’s Day and the A Day Without a Woman protests, the The Handmaid’s Tale novelist conducted a Reddit Ask Me Anything to coincide with the soon-to-premiere Hulu version of her most famous work. Dystopia, feminism and literature are, of course, among the discussion topics. A few exchanges follow.

Question:

Thank you so much for writing The Handmaid’s Tale. It was the book that got me hooked on dystopian novels. What was your inspiration for the story?

Margaret Atwood:

Ooo, three main things: 1) What some people said they would do re: women if they had the power (they have it now and they are); 2) 17th C Puritan New England, plus history through the ages — nothing in the book that didn’t happen, somewhere and 3) the dystopian spec fics of my youth, such as 1984, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, etc. I wanted to see if I could write one of those, too.

Question:

Question:

What is a book you keep going back to read and why?

Margaret Atwood:

This is going to sound corny but Shakespeare is my return read. He knew so much about human nature (+ and minus) and also was an amazing experimenter with language. But there are many other favourites. Wuthering Heights recently. In moments of crisis I go back to (don’t laugh) Lord of the Rings, b/c despite the EVIL EYE OF MORDOR it comes out all right in the end. Whew.

Question:

How, if at all, has your feminism changed over the last decade or so? Can you see these changes taking place throughout your literature? Lastly, can you offer any advice for feminists of the millennial generation? What mistakes are we making/repeating? What are our priorities in this political climate?

Margaret Atwood:

Hello: I am so shrieking old that my formative years (the 40s and 50s) took place before 2nd wave late-60’s feminist/women’s movement. But since I grew up largely in the backwoods and had strong female relatives and parents who read a lot and never told me I couldn’t do such and such because of being a girl, I avoided the agit-prop of the 50s that said women should be in bungalows with washing machines to make room for men coming back from the war. So I was always just very puzzled by some of the stuff said and done by/around women. I was probably a danger to myself and others! (joke) My interest was in women of all kinds — and they are of all kinds. They are interesting in and of themselves, and they do not always behave well. But then I learned more about things like laws and other parts of the world, and history… try Marilyn French’s From Eve to Dawn, pretty massive. We are now in what is being called the 3rd wave — seeing a lot of pushback against women, and also a lot of women pushing back in their turn. I’d say in general: be informed, be aware. The priorities in the US are roughly trying to prevent the roll-back that is taking place especially in the area of women’s health. Who knew that this would ever have to be defended? Childbirth care, pre-natal care, early childhood care — many people will not even be able to afford any of it. Dead bodies on the floor will result. It is frightful. Then there is the whole issue of sexual violence being used as control — it is such an old motif. For a theory of why now, see Eve’s Seed. It’s an unsettled time. If I were a younger woman I’d be taking a self-defense course. I did once take Judo, in the days of the Boston Strangler, but it was very lady-like then and I don’t think it would have availed. There’s something called Wen-Do. It’s good, I am told.

Question:

The Handmaid’s Tale gets thrown out as your current worst-case scenario right now but I read The Heart Goes Last a few months ago and I was surprised how possible it felt. Was there a specific news story or event that compelled you to write that particular story?

Margaret Atwood:

The Heart Goes Last — yes, came from my interest in what happens when a region’s economy collapses and people are really up against it, and the only “business” in which people can have jobs is a prison. It pushes the envelope (will there really be some Elvis robots?) but again, much of what was only speculation then is increasingly possible.

Question:

How did your experience with the 2017 version differ from the 1990 version of The Handmaid’s Tale?

Margaret Atwood:

Different times (that world is closer now!) and a 90 minute film is a different proposition from a 10 part 1st season series, which can build out and deep dive because it has more time. The advent of high-quality streamed or televised series has opened up a whole new set of possibilities for longer novels. We launched the 1990 film in West and then East Berlin just as the Wall was coming down… and I started writing book when the Wall was still there… Framed it in people’s minds in a different way. Also, then, many people were saying “It can’t happen here.” Now, not so much….•

Tags: Margaret Atwood

Economist Tyler Cowen just did a fun Ask Me Anything at Reddit, discussing driverless cars, the Hyperloop, wealth redistribution, Universal Basic Income, the American Dream, etc.

Cowen also discusses Peter Thiel’s role in the Trump Administration, though his opinion seems too coy. We’re not talking about someone who just so happens to work for a “flawed” Administration but a serious supporter of a deeply racist campaign to elect a wholly unqualified President and empower a cadre of Breitbart bigots. Trump owns the mess he’s creating, but Thiel does also. The most hopeful thing you can say about the Silicon Valley billionaire, who was also sure there were WMDs in Iraq, is that outside of his realm he has no idea what he’s doing. The least hopeful is that he’s just not a good person.

A few exchanges follow.

Question:

What is an issue or concept in economics that you wish were easier to explain so that it would be given more attention by the public?

Tyler Cowen:

The idea that a sound polity has to be based on ideas other than just redistribution of wealth.

Question:

What do you think about Peter Thiel’s relationship with President Trump?

Tyler Cowen:

I haven’t seen Peter since his time with Trump. I am not myself a Trump supporter, but wish to reserve judgment until I know more about Peter’s role. I am not in general opposed to the idea of people working with administrations that may have serious flaws.

Question:

In a recent article by you, you spoke about who in the US was experiencing the American Dream, finding evidence that the Dream is still alive and thriving for Hispanics in the U.S. What challenges do you perceive now with the new Administration that might reduce the prospects for this group?

Tyler Cowen:

Breaking up families, general feeling of hostility, possibly damaging the economy of Mexico and relations with them. All bad trends. I am hoping the strong and loving ties across the people themselves will outweigh that. We will see, but on this I am cautiously optimistic.

Question:

Do you think convenience apps like Amazon grocery make us more complacent?

Tyler Cowen:

Anything shipped to your home — worry! Getting out and about is these days underrated. Serendipitous discovery and the like. Confronting the physical spaces we have built, and, eventually, demanding improvements in them.

Question:

Given that universal basic income or similar scheme will become necessity after large scale automation kicks in, will these arguments about fiscal and budgetary crisis still hold true?

And with self driving cars and tech like Hyperloop, wouldn’t the rents in the cities go down?

Tyler Cowen:

Driverless cars are still quite a while away in their most potent form, as that requires redoing the whole infrastructure. But so far I see location only becoming more important, even in light of tech developments, such as the internet, that were supposed to make it less important. It is hard for me to see how a country with so many immigrants will tolerate a UBI. I think that idea is for Denmark and New Zealand, I don’t see it happening in the United States. Plus it can cost a lot too. So the arguments about fiscal crisis I think still hold.

Question:

What is the most underrated city in the US? In the world?

Tyler Cowen:

Los Angeles is my favorite city in the whole world, just love driving around it, seeing the scenery, eating there. I still miss living in the area.

Question:

I am a single guy. Can learning economics help me find a girlfriend?

Tyler Cowen:

No, it will hurt you. Run the other way!•

Tags: Peter Thiel, Tyler Cowen

In the Financial Times interview with Daniel Dennett I recently blogged about, a passage covers a compelling idea hatched by the philosopher and MIT’s Deb Roy in “Our Transparent Future,” a 2015 Scientific American article. The academics argue that the radical transparency now taking hold because of new technological tools, which will only grow more profound as we are lowered even further into a machine with no OFF switch, is akin to the circumstances that may have catalyzed the Cambrian explosion.

In that epoch, it might have been an abundance of light that shined through in a newly transparent atmosphere which forced organisms to adapt and led to tremendous growth–and also death. Dennett and Roy believe that society’s traditional institutions (government, marriage, education, etc.) are facing the same challenge to reinvent themselves or else, due to the tremendous flow of information we have today at our fingertips. Now that privacy is all but impossible, what is the best way to arrange ourselves?

The opening:

MORE THAN HALF A BILLION YEARS AGO A SPECTACULARLY CREATIVE burst of biological innovation called the Cambrian explosion occurred. In a geologic “instant” of several million years, organisms developed strikingly new body shapes, new organs, and new predation strategies and defenses against them. Evolutionary biologists disagree about what triggered this prodigious wave of novelty, but a particularly compelling hypothesis, advanced by University of Oxford zoologist Andrew Parker, is that light was the trigger. Parker proposes that around 543 million years ago, the chemistry of the shallow oceans and the atmosphere suddenly changed to become much more transparent. At the time, all animal life was confined to the oceans, and as soon as the daylight flooded in, eyesight became the best trick in the sea. As eyes rapidly evolved, so did the behaviors and equipment that responded to them.

Whereas before all perception was proximal—by contact or by sensed differences in chemical concentration or pressure waves—now animals could identify and track things at a distance. Predators could home in on their prey; prey could see the predators coming and take evasive action. Locomotion is a slow and stupid business until you have eyes to guide you, and eyes are useless if you cannot engage in locomotion, so perception and action evolved together in an arms race. This arms race drove much of the basic diversification of the tree of life we have today.

Parker’s hypothesis about the Cambrian explosion provides an excellent parallel for understanding a new, seemingly unrelated phenomenon: the spread of digital technology. Although advances in communications technology have transformed our world many times in the past—the invention of writing signaled the end of prehistory; the printing press sent waves of change through all the major institutions of society—digital technology could have a greater impact than anything that has come before. It will enhance the powers of some individuals and organizations while subverting the powers of others, creating both opportunities and risks that could scarcely have been imagined a generation ago.

Through social media, the Internet has put global-scale communications tools in the hands of individuals. A wild new frontier has burst open. Services such as YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, Instagram, WhatsApp and SnapChat generate new media on a par with the telephone or television—and the speed with which these media are emerging is truly disruptive. It took decades for engineers to develop and deploy telephone and television networks, so organizations had some time to adapt. Today a social-media service can be developed in weeks, and hundreds of millions of people can be using it within months. This intense pace of innovation gives organizations no time to adapt to one medium before the arrival of the next.

The tremendous change in our world triggered by this media inundation can be summed up in a word: transparency. We can now see further, faster, and more cheaply and easily than ever before—and we can be seen. And you and I can see that everyone can see what we see, in a recursive hall of mirrors of mutual knowledge that both enables and hobbles. The age old game of hide-and-seek that has shaped all life on the planet has suddenly shifted its playing field, its equipment and its rules. The players who cannot adjust will not last long.

The impact on our organizations and institutions will be profound. Governments, armies, churches, universities, banks and companies all evolved to thrive in a relatively murky epistemological environment, in which most knowledge was local, secrets were easily kept, and individuals were, if not blind, myopic. When these organizations suddenly find themselves exposed to daylight, they quickly discover that they can no longer rely on old methods; they must respond to the new transparency or go extinct.•

Tags: Daniel Dennett, Deb Roy

A little more on Cambridge Analytica, which Carole Caldwalla reported on recently in the Guardian. The audience-targeting company is being given significant credit by some for powering the Trump campaign to Electoral College victory. My main hesitation with believing online fake news was an predominant factor in the recent election is that Trump won overwhelmingly with older Americans, who seem to have been more plugged into Fox News than Facebook. It may have played a role, but did it really have a greater impact than, say, a legacy-media company like the New York Times, running an un-skeptical headline above the fold about the FBI suspiciously reopening the investigation into the Clinton emails? Or Russia hacking the election? It’s hard to untangle what just went on, but looking for a single smoking gun will probably always prove unsatisfactory.

From Nicholas Confessore and Danny Hakim of the New York Times:

Cambridge Analytica’s rise has rattled some of President Trump’s critics and privacy advocates, who warn of a blizzard of high-tech, Facebook-optimized propaganda aimed at the American public, controlled by the people behind the alt-right hub Breitbart News. Cambridge is principally owned by the billionaire Robert Mercer, a Trump backer and investor in Breitbart. Stephen K. Bannon, the former Breitbart chairman who is Mr. Trump’s senior White House counselor, served until last summer as vice president of Cambridge’s board.

But a dozen Republican consultants and former Trump campaign aides, along with current and former Cambridge employees, say the company’s ability to exploit personality profiles — “our secret sauce,” Mr. Nix once called it — is exaggerated.

Cambridge executives now concede that the company never used psychographics in the Trump campaign. The technology — prominently featured in the firm’s sales materials and in media reports that cast Cambridge as a master of the dark campaign arts — remains unproved, according to former employees and Republicans familiar with the firm’s work.

“They’ve got a lot of really smart people,” said Brent Seaborn, managing partner of TargetPoint, a rival business that also provided voter data to the Trump campaign. “But it’s not as easy as it looks to transition from being excellent at one thing and bringing it into politics. I think there’s a big question about whether we think psychographic profiling even works.”•

Late to Industrialization, China entered the process knowing what much of the Western world had to learn the hard way in the 1970s: Urbanizing and modernizing an entire nation brings with it tremendous economic growth, but it can’t be sustained by the same methods–or perhaps at all–when the mission is complete. It’s a one-time-only bargain.

A richer nation can’t grow endlessly on the production of cheap exports, so the newly minted superpower is pivoting more to domestic demand, a nuance no doubt lost in the Trump Administration’s ham-handed appreciation of global politics. In “Trump’s Most Chilling Economic Lie,” a Joseph Stiglitz Vanity Fair “Hive” article, the economist highlights the insanity of America engaging in a trade war with China and expecting to emerge the richer. An excerpt:

Trump’s team may be tempted to conclude, naively, that because China exports so much more to the U.S. than the U.S. exports to China, the loss of a huge export market would hurt them more than it would hurt us. This reasoning is too simplistic by half. China’s government has far more control over the country’s economy than our government has over ours; and it is moving from export dependence to a model of growth driven by domestic demand. Any restriction on exports to the U.S. would simply accelerate a process already underway. Moreover, China’s government has the resources (it’s still sitting on some $3 trillion of reserves) and instruments to help any sector that has been shut out—and in this respect, too, China is better placed than the U.S.

China has already shown how it is likely to respond if Trump should launch a trade war. At Davos, President Xi Jinping came out as the great supporter of globalization and the international rule of law—as well China should. China, with its large emerging middle class, is among the big beneficiaries of globalization. Critics have said that China does not always play fair. They complain that as China has grown, it has taken away some of the privileges, some of the tax preferences, that it gave to foreigners in earlier stages of development. They are unhappy, too, that some Chinese firms have learned quickly how to compete—some of them even appropriating ideas from others, just as we appropriated intellectual property from Europe more than a century ago.

It is worth noting that, although large multinationals complain, they are not leaving. And we tend to forget the extensive restrictions we impose on Chinese firms when they seek to invest in the U.S. or buy high-tech products. Indeed, the Chinese frequently point out that if the U.S. lifted those restrictions, America’s trade deficit with China would be smaller.

China’s first response will be to try to find areas of cooperation. They are experts in construction. They know how to build high-speed trains. They might even provide some financing for these projects. Given Trump’s rhetoric, though, I suspect that such cooperation is just a dream.

If Trump insists on an adversarial stance, China is likely to respond within the framework of international law even if Trump puts little weight on such agreements—and thus is not likely to retaliate in a naive, tit-for-tat way. But China has made it clear that it will respond. And if history is any guide, it will respond both forcefully and intelligently, hitting us where it hurts economically and politically—where, for instance, cutbacks in purchases by China will lead to more unemployment in congressional districts that are vulnerable, influential, or both. If Boeing’s order book is thin, it might, for instance, cancel its purchases of Boeing planes.•

Tags: Donald Trump, Joseph Stiglitz

Some things take on a life of their own, even when they’re not actually living. AI will likely slot into this category.

When Bill Gates suggests America tax robots not only to provide opportunities to those squeezed from the middle class but to also slow down innovation, he’s analyzing the situation as it if it existed inside a vacuum. That’s not the way technology proceeds.

Developing new tools is part of a constant competition among and within states and corporations. Innovating is paramount to maintaining a competitive edge in the marketplace or battlefield. Of course, holding your position or gaining an advantage means a nation (or nations) may be careering down a perilous path. Being militarily prepared for danger can, paradoxically, be very dangerous. The same will be true of biotech.

From Morgan Chalfant’s The Hill story about the surprising speed with which robotic soldiers may be reporting for duty:

Peter Singer, a strategist at the New America Foundation, said that artificial intelligence is among potential “disruptions” being developed in the realm of cyber conflict.

“It’s not just when is it going to happen, but we don’t yet know is it going to privilege the offense or defense, what are going to be the affects of it,” Singer said, recommending that Congress hold a classified hearing on where the U.S. stands in comparison to likely adversaries on this capability.

“We don’t want to fall behind,” he said.

Healey expressed concerns about the possibility of artificial intelligence augmenting our adversaries’ offensive capabilities more significantly than the United States’ defense of its critical infrastructure.

“The part of it that particularly worries me the most is that on the defensive side many people are thinking that artificial intelligence, new heuristics, better analytics and automation are going to help the defense, that if only we can roll these things out faster we will be better and the system will be more stable,” Healey explained.

“I think that these technologies are going to aid the offense much more than it aids the defense because to defend against these kinds of attacks, you need your own super computer,” he continued.

Healey warned that while the Pentagon can afford computer systems necessary to defend against adversaries using artificial intelligence, small- or mid-sized enterprises that own U.S. critical infrastructure cannot.

“It leaves much of America undefended,” he said.•

Tags: Morgan Chalfant

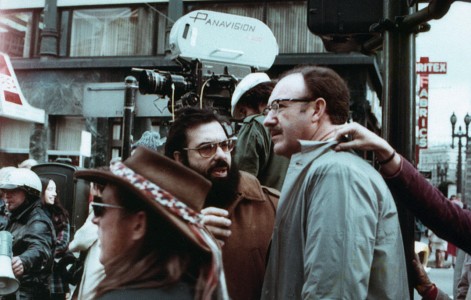

Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation is the “little” 1974 psychological thriller he squeezed in between the first two Godfather films, which fast-forwarded the disquiet of Antonioni’s Blow-Up into the Watergate Era, even if the director has always considered it more a personal than political film. The movie, which hangs on San Francisco surveillance expert Harry Caul’s descent into madness, remains a classic and has actually grown in stature as the Digital Age replaced the analog one. When I wrote briefly about the cerebral movie six years ago, I concluded with this:

Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation is the “little” 1974 psychological thriller he squeezed in between the first two Godfather films, which fast-forwarded the disquiet of Antonioni’s Blow-Up into the Watergate Era, even if the director has always considered it more a personal than political film. The movie, which hangs on San Francisco surveillance expert Harry Caul’s descent into madness, remains a classic and has actually grown in stature as the Digital Age replaced the analog one. When I wrote briefly about the cerebral movie six years ago, I concluded with this:

In the era that saw the downfall of an American President who listened to the tapes of others and erased his own, The Conversation was amazingly relevant, but in some ways it may be even more meaningful in this exhibitionist age, in which we gleefully hand over our privacy to satisfy our egos. As Caul and Nixon learned, and as we may yet, those who press PLAY don’t always get to choose when to press STOP.•

This weekend, we had a sitting American President (baselessly) accuse his predecessor of tapping his phone lines, all the while the Intelligence Community searches for real tapes of this Administration’s officials conspiring with the Kremlin during the campaign. Such evidence would be treasonous.

It’s not shocking that Trump’s viciously ugly brand of nostalgia has forced us backwards into a Cold Way type of paranoia, in which 20th-century espionage is predominant. The greater insight to take from The Conversation may be more about the near future, however, when nobody has to hit PLAY because there’s no longer a STOP.

In an amazing find, the good people at Cinephilia & Beyond published a 1974 Filmmakers Newsletter interview in which Brian De Palma quizzed Coppola about this masterwork. It’s more a discussion of cinema than of Watergate, and there’s a very interesting exchange in which the subject reveals why he doesn’t regard Hitchcock with awe.

Here’s the opening:

Here’s a wonderful making-of featurette about The Conversation, which asked questions about a world where everyone is a spy and spied upon. The surprise more than 40 years later: Few seemed upset as we crept into the new order of the techno-society. We haven’t been trapped after all; we’ve logged on and signed up for it.

Autocracy instills fear and fuels paranoia not only in the people but in the autocrat as well. The walls are always moving in for a better look.

The sickening, silent video-surveillance footage that captured the Malaysian airport assassination of Kim Jong-nam, a possible weapon of mass destruction pressed against his face with a piece of cloth, isn’t even likely the most recent example of the madness of tyranny at work, not with the mounting, suspicious body count of Russian diplomats of the past few months. Regardless of what our current President may say, Americans don’t dispatch of their political enemies like murderous despots.

Long before Kim Jong-un terrorized North Korea, Joseph Stalin did the same to the Soviet Union, and Leon Trotsky was the “brother” who most concerned him, even though he had been exiled long ago and far away in Mexico.

The end came in 1940 for the Marxist theorist. What machine guns failed to do in May, a romantic interlude and an ice ax accomplished before summer’s end. A Brooklyn woman who’d become part of Trotsky’s inner circle unwittingly had an affair with Russian operative Ramón Mercader, which allowed him access to his prey. A single blow, though somewhat botched, proved decisive.

Three articles on the topic from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle follow.

From May 24, 1940:

From August 21, 1940:

From August 22, 1940:

A few excerpts follow.

From Calvin Woodward and Christopher S. Rugaber of the Associated Press:

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Donald Trump boasted in his speech to Congress that new money “is pouring in” from NATO partners, which it isn’t. He also took credit for corporate job expansion and military cost savings that actually took root under his predecessor.

A look at some of his claims Tuesday night:

TRUMP: Speaking of the NATO alliance, “Our partners must meet their financial obligations. And now, based on our very strong and frank discussions, they are beginning to do just that. In fact, I can tell you the money is pouring in. Very nice. Very nice.”

THE FACTS: No new money has come pouring in from NATO allies. Defense Secretary Jim Mattis made a strong case when he met with allied defense ministers at a NATO meeting last month, pressing them to meet their 2014 commitment to spend 2 percent of their gross domestic product on defense by 2024. He and other leaders said the allies understood the message and there was some discussion about working out plans to meet the goal.

Only five of the 28 member countries are meeting the 2 percent level, and no new commitments have been made since the NATO meeting.

In fact, Germany’s foreign minister said Wednesday he is skeptical about his country’s plans to increase defense spending, saying it could raise concerns in Europe by turning Germany into “a military supremacy.” German Chancellor Angela Merkel has said her country will meet its commitment to raise defense spending by the 2024 deadline. In any event, the commitment is for these nations to spend more on their own military capabilities, which would strengthen the alliance, not to hand over money.•

From Micah Zenko of Foreign Policy:

The White House pledged that President Donald Trump’s prime-time joint address to Congress on Tuesday night would “lay out an optimistic vision for the country,” adding that the theme would be a “renewal of the American spirit.” In keeping with his many previous speeches, Trump was incapable of delivering such an address. Instead, he offered repeated encouragement to Americans to show the “bravery to express the hopes that stir our souls,” which resembled nothing so much as the performance of a motivational speaker, only with less specific guidance for how the audience might improve their lives.

One poignant moment, however, unintentionally revealed a great deal not just about what sort of leader the president is but how disengaged America’s political class has always been with the country’s more than 15-year war on terrorism. In an overt and calculated effort to deflect attention from a failed military operation, Trump turned to the widow of Chief Petty Officer William “Ryan” Owens, who was killed in a Navy SEAL raid in central Yemen for which, earlier in the day, the president had shirked all responsibility.

In fact, he went beyond shirking responsibility for the Jan. 28 raid, which killed Owens along with several suspected al Qaeda-affiliated fighters and an unknown number of Yemeni civilians — all while producing no significant intelligence, according to Defense Department officials. On Tuesday morning, Trump took the astonishing step of blaming his subordinates. During an interview with Fox and Friends, the commander in chief declared, “This was a mission that was started before I got here. This was something [the generals] wanted to do. They came to see me; they explained what they wanted to do — the generals — who are very respected. My generals are the most respected that we’ve had in many decades, I believe. And they lost Ryan.”

In other words, Trump laid the blame for a failed military operation that he authorized on the previous administration and on the military commanders who oversaw it. This distancing of authority and redirection of accountability are unprecedented in modern military history. Several active-duty and retired military officers I have heard from in the past two days have (quietly) expressed their deep disappointment with Trump’s comments. Unfortunately, Republican congressional members who lead the oversight committees for such operations will likely defend or tolerate his actions, simply because the president belongs to their political party.•

From Charles P. Pierce of Esquire:

The speech was chock-full of barefaced non-facts regarding crime, immigrants, crime committed by immigrants, the accomplishments of the current administration, and the condition of the country when it handed itself over to his half-baked stewardship last November. I don’t care if you sell your mendacity in perfect iambic pentameter in the voice of Laurence Olivier. It’s still bullshit, and dangerous bullshit at that. And it will sell. That’s the heart and start of it. The people who bought this when it was poured out to them straight up during the campaign certainly will buy it now that it’s mixed with some sweetener lifted whole from every middle-school graduation speech ever given.

There is one portion of the speech that transcended the obvious prevarication and sent the speech spiraling into the near suburbs of outright fascism.

I have ordered the Department of Homeland Security to create an office to serve American Victims. The office is called VOICE—Victims Of Immigration Crime Engagement. We are providing a voice to those who have been ignored by our media, and silenced by special interests.

What media ignored these crimes? What special interests silenced their families? He doesn’t know and he doesn’t care.

Is it even necessary to outline how perilous to democracy this is? You can see it even without being reminded that, a) under Steve Bannon’s leadership, Breitbart inaugurated a section called “Black Crime,” or b) the Nazi regime constructed an elaborate bureaucratic mechanism to catalogue alleged Jewish crimes against innocent Aryan citizens, although you probably ought to keep those two precedents in mind. The Department of Homeland Security never has been a terrific idea, but to invest something like this new propaganda ministry with the power and influence of an actual Cabinet department is like giving Steve Bannon’s old news sewer its own Special Forces.•

From Jeet Heer of the New Republic:

While the more positive parts of the speech were articulated with generalities about working together, the dark passages were presented as vivid narratives with clear heroes and villains.

Immigrants, whether documented or not, commit less crime than other Americans, but Trump talks about these crimes with a melodramatic bluster:

Joining us in the audience tonight are four very brave Americans whose government failed them.

Their names are Jamiel Shaw, Susan Oliver, Jenna Oliver, and Jessica Davis.

Jamiel’s 17-year-old son was viciously murdered by an illegal immigrant gang member, who had just been released from prison. Jamiel Shaw Jr. was an incredible young man, with unlimited potential who was getting ready to go to college where he would have excelled as a great quarterback. But he never got the chance. His father, who is in the audience tonight, has become a good friend of mine.

Also with us are Susan Oliver and Jessica Davis. Their husbands—Deputy Sheriff Danny Oliver and Detective Michael Davis—were slain in the line of duty in California. They were pillars of their community. These brave men were viciously gunned down by an illegal immigrant with a criminal record and two prior deportations.

To address this imagined crisis, Trump said he has “ordered the Department of Homeland Security to create an office to serve American victims” of crimes committed by immigrants—a statistically minuscule problem, as crime in America goes. And in a press release sent during the speech, the White House heralded Trump’s Blue Lives Matter agenda by noting that he directed Attorney General Jeff Sessions to “develop a strategy to more effectively prosecute people who engage in crimes against law enforcement officers”—also a statistically minuscule problem. In short, Trump’s meager policy solutions aren’t commensurate with his graphic portrait of a broken America.

It’s understandable why people want to believe that the Trump of “American carnage” has pivoted into a more inspirational president. But any attention to his words makes clear that an extremely disturbing, distorted vision of America still defines this presidency.•

Tags: Calvin Woodward, Charles P. Pierce, Christopher S. Rugaber, Micah Zenko

Rebuilding the world has to rank at the top of economic low-hanging fruit of the last century. America, its forces marshaled, played a leading role in piecing together the shattered globe in the wake of WWII. Yes, four decades of unfortunate tax rates, globalization, automation and the demise of unions have all abetted the decline of the U.S. middle class, but just as true is that the good times simply ended, the job completed (more or less), the outlier ran headlong into entropy. The contents of this half-empty glass finally spilled all over the world in 2016, provoking outrageously regressive political shifts, with perhaps more states becoming submerged this year.

As An Extraordinary Time author Marc Levinson wrote in 2016 in the Wall Street Journal: “The quarter-century from 1948 to 1973 was the most striking stretch of economic advance in human history. In the span of a single generation, hundreds of millions of people were lifted from penury to unimagined riches.” In “End of a Golden Age,” an Aeon essay, the economist and journalist further argues the global circumstances of the postwar era were a one-time-only opportunity for runaway productivity, a fortunate arrangement of stars likely to never align again.

Well, never is an extremely long stretch (we hope), but the economic-growth-rate promises brought to the trail by Sanders and Trump, which have made it to the White House with the unfortunate election of the latter candidate, were at best fanciful, though delusional might also be a fair assessment. If I had to guess, I would say someday we’ll see tremendous growth again, but when that happens and what precipitates it, I don’t know. Nobody really does.

An excerpt:

When it comes to influencing innovation, governments have power. Grants for scientific research and education, and policies that make it easy for new firms to grow, can speed the development of new ideas. But what matters for productivity is not the number of innovations, but the rate at which innovations affect the economy – something almost totally beyond the ability of governments to control. Turning innovative ideas into economically valuable products and services can involve years of trial and error. Many of the basic technologies behind mobile telephones were developed in the 1960s and ’70s, but mobile phones came into widespread use only in the 1990s. Often, a new technology is phased in only over time as old buildings and equipment are phased out. Moreover, for reasons no one fully understands, productivity growth and innovation seem to move in long cycles. In the US, for example, between the 1920s and 1973, innovation brought strong productivity growth. Between 1973 and 1995, it brought much less. The years between 1995 and 2003 saw high productivity gains, and then again considerably less thereafter.

When the surge in productivity following the Second World War tailed off, people around the globe felt the pain. At the time, it appeared that a few countries – France and Italy for a few years in the late 1970s, Japan in the second half of the ’80s – had discovered formulas allowing them to defy the downward global productivity trend. But their economies revived only briefly before productivity growth waned. Jobs soon became scarce again, and improvements in living standards came more slowly. The poor productivity growth of the late 1990s was not due to taxes, regulations or other government policies in any particular country, but to global trends. No country escaped them.

Unlike the innovations of the 1950s and ’60s, which were welcomed widely, those of the late 20th century had costly side effects. While information technology, communications and freight transportation became cheaper and more reliable, giant industrial complexes became dinosaurs as work could be distributed widely to take advantage of labour supplies, transportation facilities or government subsidies. Workers whose jobs were relocated found that their years of experience and training were of little value in other industries, and communities that lost major employers fell into decay. Meanwhile, the welfare state on which they had come to rely began to deteriorate, its financial underpinnings stressed due to the slow growth of tax revenue in economies that were no longer buoyant. The widespread sharing in the mid-century boom was not repeated in the productivity gains at the end of the century, which accumulated at the top of the income scale.

For much of the world, the Golden Age brought extraordinary prosperity. But it also brought unrealistic expectations about what governments can do to assure full employment, steady economic growth and rising living standards. These expectations still shape political life today.•

The recent Presidential election revealed that U.S. citizens either have a terrible understanding of economics or they’re willing to surrender their security in the name of identity politics. Both are likely true to a significant extent.

Immigrants were blamed for the downgrading of the American worker on the trail while automation was never discussed, and Michigan voters swung to Trump, largely because Washington had supposedly forgotten about them, after the Obama Administration wagered $79 billion on bailing out the Detroit auto industry. Not too long after that salvage job by the federal branch, the state’s populace voted in an anti-union governor in Rick Snyder. The locals may have forgotten about themselves more than D.C. ever did.

Another vital topic of discussion that was never broached during the campaign was the role that contracted work has played in shrinking middle class. For several decades, American companies have been outsourcing mail-room work, maintenance, security and other “non-core” tasks to subcontractors who would save them some money by lowering salaries and reducing benefits to laborers. This shift created a separate class. Executive pay ballooned while those with more modest pay stubs took the elevator downward, further exacerbating wealth inequality.

I’ve written before about this destabilizing phenomenon. More from Eduardo Porter of the New York Times:

…Mr. Trump is missing a more critical workplace transformation: the vast outsourcing of many tasks — including running the cafeteria, building maintenance and security — to low-margin, low-wage subcontractors within the United States.

This reorganization of employment is playing a big role in keeping a lid on wages — and in driving income inequality — across a much broader swath of the economy than globalization can account for.

David Weil, who headed the Labor Department’s wage and hour division at the end of the Obama administration, calls this process the “fissuring” of the workplace. He traces it to the 1980s, when corporations under pressure to raise quarterly profits started shedding “noncore” tasks.

The trend grew as the spread of information technology made it easier for companies to standardize and monitor the quality of outsourced work. Many employers took to outsourcing to avoid the messy consequences — like unions and workplace regulations — of employing workers directly.

“It’s an incredibly important part of the story that we haven’t paid attention to,” Mr. Weil told me.

“Lead businesses — the firms that continue to directly employ workers who provide the goods and services in the economy recognized by consumers — remain highly profitable and may continue to provide generous pay for their work force,” he noted. “The workers whose jobs have been shed to other, subordinate businesses face far more competitive market conditions.”

The trend is hard to measure, since subcontracting can take many forms. But it is big.•

Tags: David Weil, Donald Trump, Eduardo Porter

In the time before centralized mass media, a whole host of traveling cons and medicine-show mountebanks could pull wool and push potions. During the era of centralized mass media, it was occasionally possible to work the masses in a big way, but mostly gatekeepers batted down these lies. In our age of decentralized communications, which began with President Reagan signing away the Fairness Doctrine and became fully entrenched with cable news and the Internet, the sideshow, now residing in the center ring, has never fooled more people who should know better.

One of the Barnums of this bizarre moment is right-wing radio talker Alex Jones, a compulsive eater and apeshit peddler of strange conspiracy theories that usually have an anti-government or bigoted bent. He is the kind of kook who would have been calling into late-night radio shows about UFOs in decades past, only to be hung up on by annoyed hosts. Today his strange fake-news impulses have provided him with a direct line to a White House led by a President who would have been laughed off the campaign trail in any reasonably decent and enlightened age.

All of this has been enabled by a new form of hyper-democracy that resists checks and balances, in which every idea is equal true or not. It’s a scary moment in which anything–anything–is possible.

From Veit Medick’s great Spiegel profile of Jones, a Texas-sized F.O.T. (Friend of Trump):

Jones is stunned that not all Americans share his panicked view of the “jihadists.” Indeed, he believes the threat is so great that it would be best not to allow anyone at all to enter the United States anymore.

“Please forget the Statue of Liberty,” Jones says during a break. “It’s a symbol of propaganda. We should stop worshipping it and bending down to every Third World population that shows up with TB and leprosy.”

‘Foot Soldiers in the Trump Revolution’

Jones now plans to open an office in Washington. He says might hire 10 people to report on the White House, almost like a traditional media organization. He will be getting help from Roger Stone, a radical adviser to the president, who wrote a book in which he described former President Bill Clinton as a serial rapist without providing any proof. Under a deal reached between the two men, Stone began hosting the Alex Jones show for one hour a week a short time ago. “Elitists may laugh at his politics,” Stone says, but “Alex Jones is reaching millions of people, and they are the foot soldiers in the Trump revolution.”

It’s afternoon, and Jones is walking through the studio, his adrenaline level high and his blood sugar low. He needs to get something to eat. Platters of BBQ – chicken, beef and sausages – are set out on a table in the conference room. “Good barbecue,” says Jones. “You tasted it already?”

He piles up food onto a plastic plate, and then he suddenly takes off his shirt without explanation. With his bare torso, he sits there and shovels meat into his mouth, a caricature of manliness, but also a show of power to the reporter sitting in front of him. He can do as he pleases.

Then Jones gets up and holds out a sausage. “Wanna suck?” he asks.•

Tags: Alex Jones, Veit Medick

Futurist Thomas Frey has published “25 Shocking Predictions about the Coming Driverless Car Era in the U.S.,” a Linkedin article which envisions a time in the near future when almost all vehicles are autonomous and individual ownership has become a thing of the past.

Of course the idea that driverless will be imminently perfected and come to dominate the streets, roads and highways in, say, the next 15 years, is the most stunning of all prognostications and certainly not a sure thing. Technological and legislative hurdles most be surmounted and those unpredictable humans must be willing to let go of the wheel, if Frey’s “explosive transformation” is to proceed.

It’s certainly not impossible. Think of the monumental changes the Internet has brought in its 20+ years of wide usage and the way smartphones have rearranged life in only a decade. Driverless may do the same or perhaps we’ll all be talking when we’re old and gray about how the revolution never quite arrived.

If it does materialize, one big headache in addition to the jobs that will be shed too quickly for society to absorb is that we’ll rest inside surveillance devices while surveillance devices rest inside our pockets. We’ll be too deep inside the machine to ever extricate ourselves.

The opening two items:

1.) Life expectancy of autonomous vehicles will be less than 1 year

I’ve been doing some math on driverless cars and came to the startling conclusion that autonomous cars will wear out in as little as 9-10 months.Yes, car speeds will be slower in the beginning, but within ten years as speeds increase and cars begin to average 60-70 mph on open freeways, a single car could easily average 1,000 miles a day.

Over a 10-month period, a single car could travel as much as 300,000 miles.

Cars today are only in use 4% of the day, less than an hour a day. An electric autonomous vehicle could be operating as much as 20 hours a day or 21 times as much as the average car today.

For an electric autonomous vehicle operating 24/7, that still leaves plenty of time for recharging, cleaning, and maintenance.

It’s too early to know what the actual life expectancy of these vehicles will be, but it’s a pretty safe assumption that it will be far less than the 11.5 years cars are averaging today.

2.) One Autonomous Car will Replace 30 Traditional Cars

2028-2030 will be the years of peak messiness for the driverless car revolution. The number of autonomous vehicles will grow quickly but they will be intermingled with traditional driver-cars.

Drivers bring with them a hard-to-quantify human variable, and that’s what makes driving today such problem-riddled experience.

There are roughly 258 million registered cars in the U.S. and replacing them will be a long drawn out process. But here’s what most people don’t understand. One autonomous vehicle that we can be summoned from a local fleet will replace 30 traditional cars.

For a city of 2 million people, a fleet of 30,000 autonomous vehicles will displace 50% of peak commuter traffic.**

During off-peak times, 30,000 autonomous vehicles will handle virtually all other transportation needs. Peak traffic times that will be the hardest to manage.•

Tags: Thomas Frey

Anti-Semitism, racism, sexism, xenophobia, Islamophobia and other evils have been ushered into the mainstream by the opportunists and hatemongers who helped enable Donald Trump into the Oval Office, and it makes no difference that some of them fall into the very groups now being targeted (Jared Kushner, Ivanka Trump and Stephen Miller, namely).

In the early days of the GOP nomination process, when it seemed done deal that Donald Trump would soon fall from the race after disgracefully gaining attention for his idiotic “brand,” Edward Luce of the Financial Times warned that even if the Mussolini-Lampanelli madman fell from the sky, the dark clouds that had formed would not go away. They would spread, becoming more ominous.

Then the worst of all possible outcomes occurred when Trump won the Electoral College, with the aid of Putin, Comey, neo-Nazis and so-called geniuses like Peter Thiel and David Gelernter. Now we have Indian people shot in Kansas, bigoted domestic terrorists arrested for murderous plots and Jewish cemeteries desecrated. Meanwhile, international scholars are interrogated at airports and undocumented workers flee for the Canadian border, willing to sacrifice fingers and toes to frostbite. That’s the nightmare version of America–the un-America.