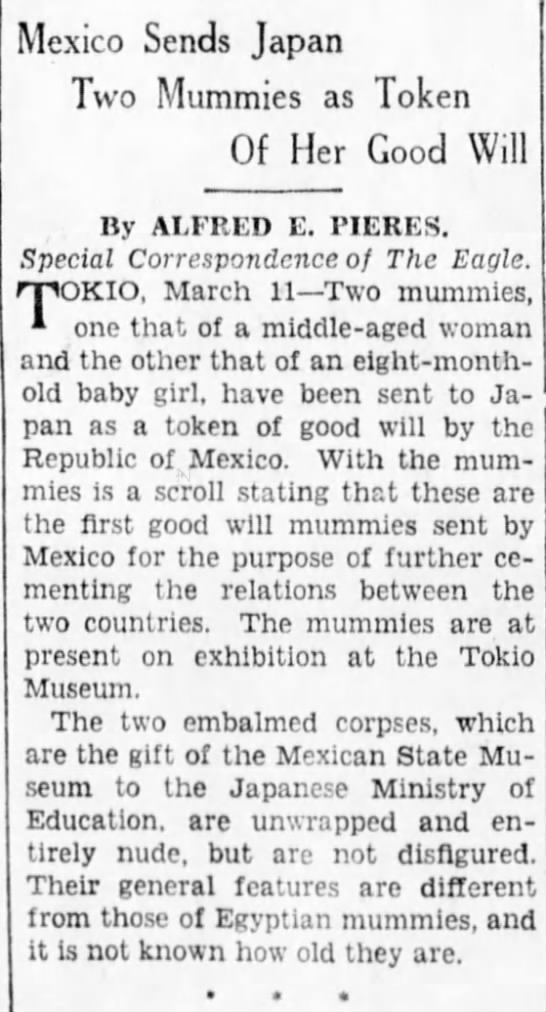

From the April 26, 1925 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

You are currently browsing the archive for the Old Print Articles category.

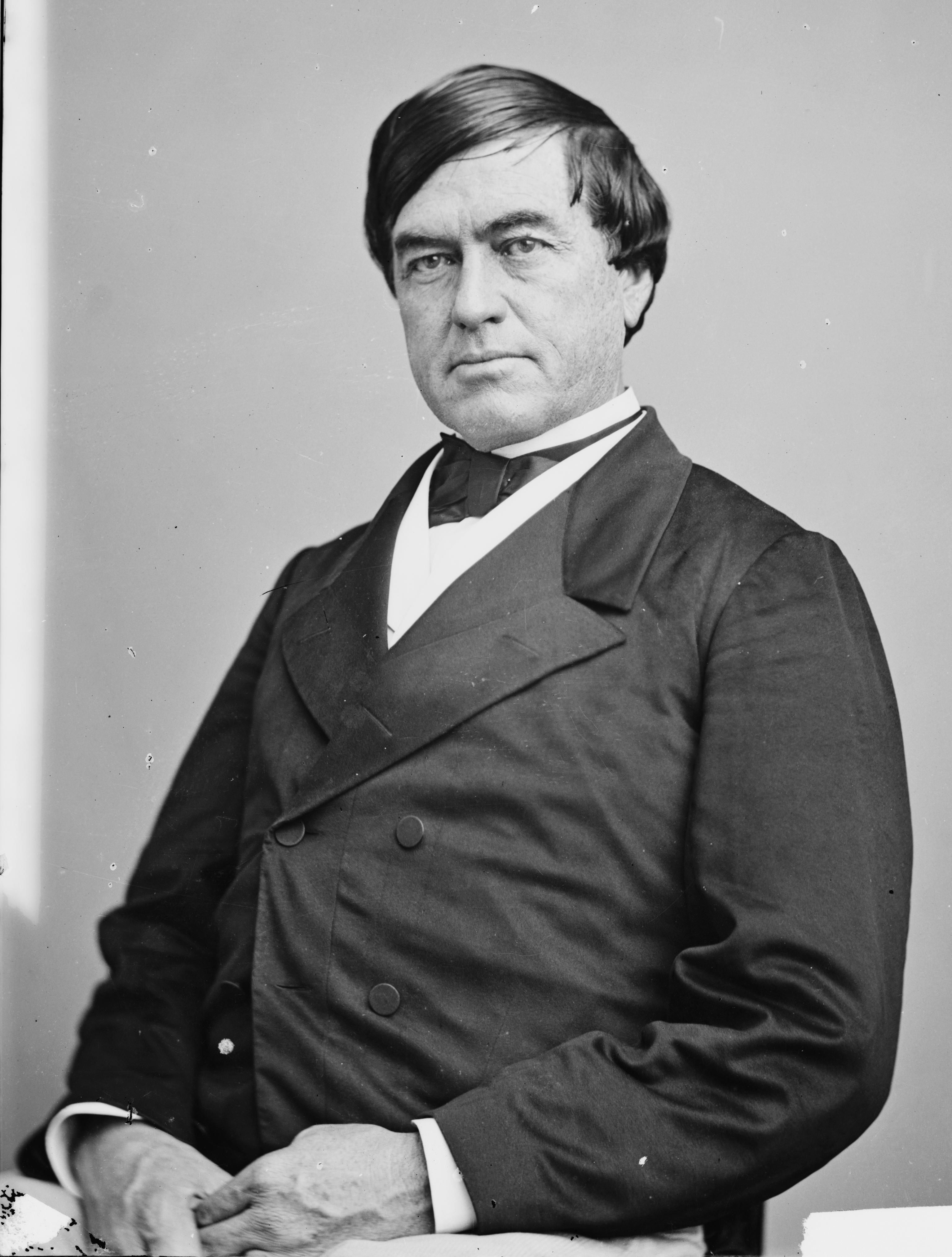

Cassius Marcellus Clay of Kentucky was a liberator, mostly.

A general who served the Union during the Civil War, he was an abolitionist from a family of slave owners who went mental in his dotage, essentially imprisoning a very reluctant 15-year-old wife when he was in his eighties. He was also a politician, an expert duelist, a Yale graduate and the U.S. Minister to Russia under President Lincoln. He was a wonderful and, eventually, terrible man.

It’s his post in St. Petersburg that reminded me of him, as he’s mentioned in a book I just read, Ian Frazier’s Travels in Siberia, which I consider to be part of an unofficial trilogy by the great reporter, along with Great Plains and On the Rez, of volumes by a tourist of sorts who lingers as long as you can without becoming a local.

From an article of the death of the nonagenarian in the July 23, 1903 New York Times:

Gen. Cassius Marcellus was famous for such a multitude of daring deeds, political feats, and personal eccentricities that it is hard to choose any one act or characteristic more distinguished than the rest. As a duelist, always victorious, he was said to have been implicated in more encounters and to have killed more men than any fighter living. As a politician he was especially famous for his anti-slavery crusades in Kentucky, having become imbued with abolition principles while he was a student at Yale, despite the fact that his father was a wealthy slave owner. As a diplomat while Minister to Russia during and after the civil war, he took a prominent part in the negotiations that resulted in the annexation of Alaska.

The act of Gen. Clay’s life that has commanded most attention in recent years was his marriage to a fifteen-year-old peasant girl after he had reached his eighty-fourth birthday. In 1887, he had married his first wife, Miss Warfield, a member of an aristocratic family of slave holders, and years afterward when he had become an ardent disciple of Tolstoi, he came to the conclusion that he ought to wed a “daughter of the people.” In November, 1894, he chose Dora Richardson, the daughter of a woman who had been a domestic for some time in his mansion at White Hall, near Lexington.

When the little girl became his wife, the General proceeded to employ a governess for her. She rebelled. Then he sent her to the same district school she had attended previously. The fact that he supplied her with the most beautiful French gowns and lavished money upon her, she did not consider compensations for the teasing she got at the hands of her fellow-pupils. In two months he had to take her back home, still uneducated.

The old warrior’s eccentricities increased during his declining years, and after his latest marriage he thought little of anything except his dream that some ancient enemy was trying to murder him and his “peasant wife,” as he called her. She, in spite of his kindnesses, kept running away from White Hall, and finally he decided he must get a divorce. This he did, charging her with abandonment. She soon married a worthless young mountaineer named Brock, who was once arrested for counterfeiting. Then the General began to plot to get her back, having already given a farm and house to her and her new husband, only to hear that Brock sold the property. At last Brock died, and a few months ago dispatches from Kentucky stated that the General was trying in vain to prevail upon his “child wife” to return to him. She refused persistently, never having outgrown the dislike for the luxurious life with which he surrounded her and still preferring the simple country existence to which she was born.•

Tags: George Heiser

In the days before telegraph and Morse code let alone radio, TV and the Internet, reports about events that occurred in Europe wouldn’t reach America for several days. A newspaper in New York came up with a novel (and highly irresponsible) way to bridge the information gap: pay a clairvoyant tell them what happened. A story in the April 19, 1860 Brooklyn Daily Eagle recalls the peculiar stunt which unsurprisingly delivered inaccurate information about one of history’s most pivotal bouts.

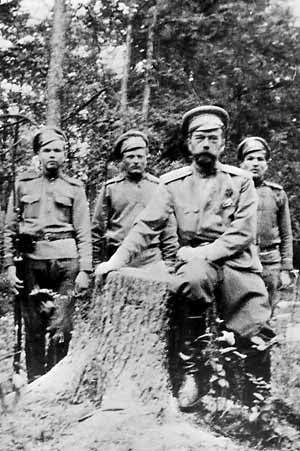

It began auspiciously for Nicholas II, though it didn’t end well.

The last of the Russian tsars assumed power at a youthful age in 1894 after his father, Alexander III, was assassinated. Nicholas II, who at most possessed modest political, economic and military skills, was not the optimal choice to lead a nation even under the best of circumstances, but no one likely could have restrained the sweep of history that was to upturn the embattled nation. It ended for Russia with a successful revolution in 1917, of course, and basement executions in Ekaterinburg the following year for the last emperor, his loved ones and minions.

Even from the start, many thought the new leader wouldn’t last the tumultuous times, as evidenced by an article that ran in the November 3, 1894 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, two days after his father died.

Tags: Alexander III, Nicholas II

Just after David Bowie’s death, Saturday Night Live reran his December 5, 1979 performance, in which he was accompanied by Klaus Nomi and Joey Arias. While singing “The Man Who Sold the World,” Bowie donned a geometrically daring suit that seemed torn from Lewis Carroll’s REM stage. It was all very cutting edge–in 1923.

That’s when the artist Sonia Delaunay dreamed up a similar design for the Tristan Tzara play The Gas Heart. The prolific visionary, who coincidentally died ten days before the aforementioned Bowie appearance, was the subject of a 1924 Brooklyn Daily Eagle profile, thanks to her outré outfits.

Words from a late-life Delaunay, for those of you who know French.

Tags: David Bowie, Sonia Delaunay, Tristan Tzara

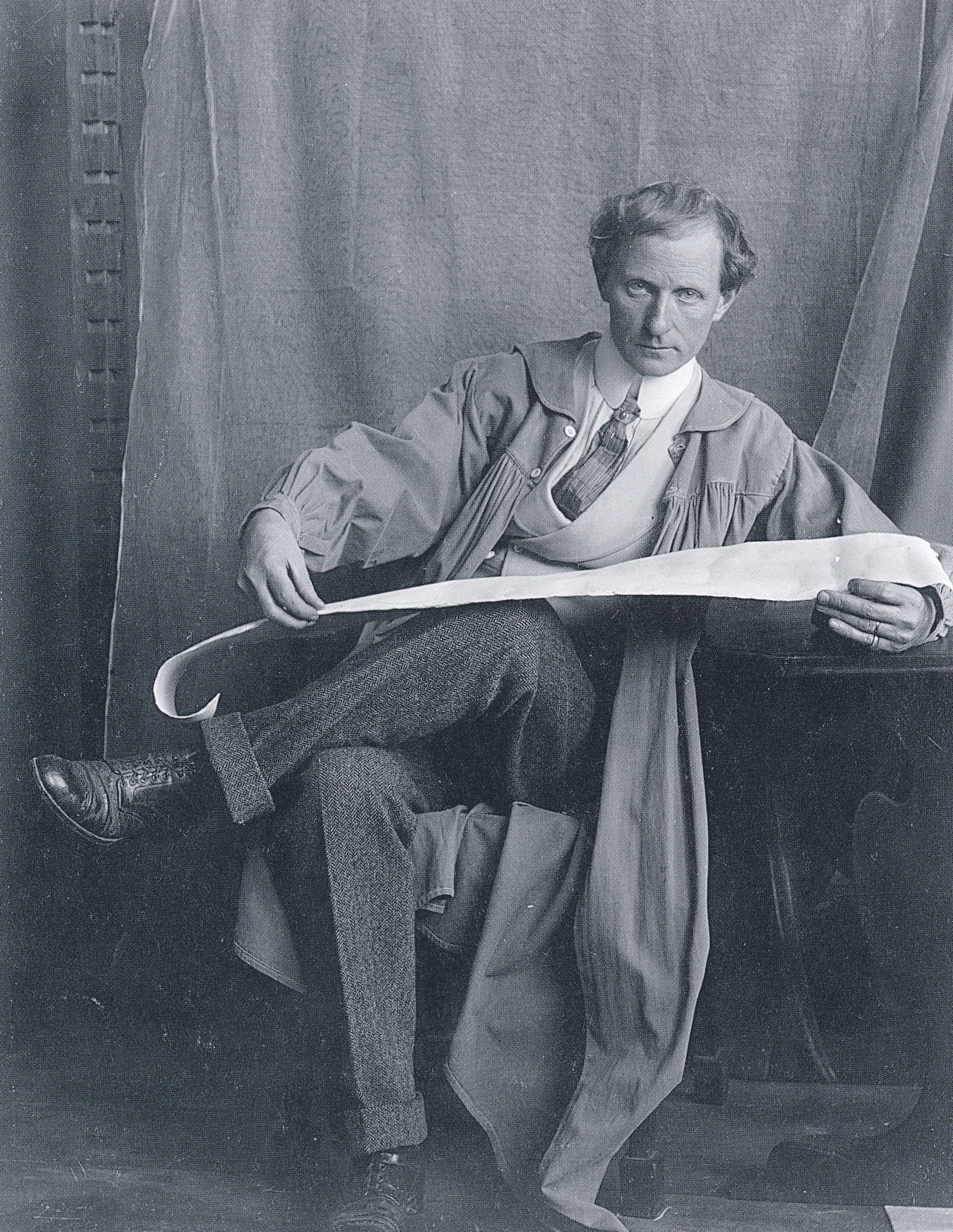

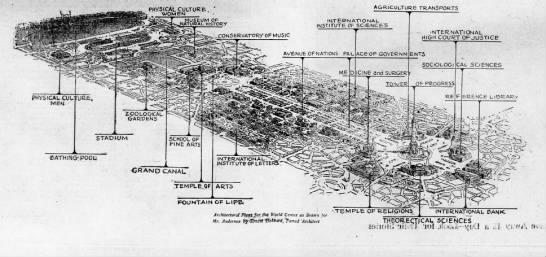

Like most who entertain top-heavy fantasies for reimagining the world, the sculptor and urban planner Hendrik Christian Andersen was a bit of a buffoon.

The Norwegian-American artist truly believed that if he could build a flawless city of beauty and learning that knew no nationalist bounds, the entire world would be inspired to perfection. Not only was it an asinine political fantasy, but it somehow led Andersen into the arms of the vulgar, murderous clown Benito Mussolini, a former drifter and agitator who had horrified the world in the 1920s by coming to absolute power in Italy. Il Duce, no doubt enamored with the pomposity of the project, promised the visionary the land and resources to realize his dream. The Shangri-La was ultimately never built, but the “soft-voiced idealist,” as the artist was described, was still speaking fondly of Mussolini into the middle of the 1930s. Andersen died in Rome in 1940, not living long enough to see his patron deservedly face the business end of a meat hook. An article in the June 19, 1927 Brooklyn Daily Eagle recalls the proposed series of stately pleasure-domes.

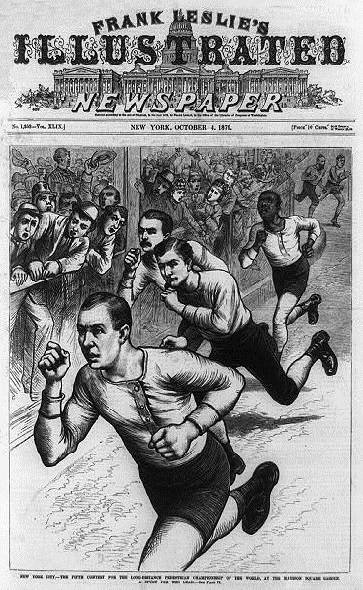

When the world was slower, much slower, a quick gait could produce a huge gate.

Such was the case with pedestrianism, a pre-automobile sensation in which competitors would race-walk cross-country or do ceaseless laps around an arena track as bleary-eyed spectators were mesmerized by the oft-lengthy exhibitions of slow-twitch muscle fiber.

An excerpt from a report in the March 4, 1882 Brooklyn Daily Eagle about one such six-day contest, a blend of footrace and dance marathon, before a large Madison Square Garden audience that alternately yelled and yawned:

Popular interest in the race of the champions touched its highest point to-day. The opening of the last day of the walk was witnessed by over two thousand spectators. Fully one-half of these had lingered in Madison Square Garden all night. Drowsy and unkempt, with grimy faces and dusty apparel, they shivered behind their upturned coat collars, determined to see the battle out. The management’s order of ‘no return checks’ had far more unpleasant significance for them than hours of discomfort in the barnlike building. The permanent lodger in a six days’ match usually makes his bed upon a coal box, in a grocery wagon or beneath the roof of the police lodging room. Accordingly, it is his habit to come to the garden at the beginning of a race and remain for a full week, or until he is removed by the employees to make way for some more profitable customers. This contest had its full share of these persistent individuals. Beside them, many sporting men remained until almost daybreak, attracted by the enormous scores rolled up by the pedestrians and speculations as to what they would do in the way of the beating of the record. It was conceded that Hazael and Fitzgerald would surpass all previous performances. Hazael’s wonderful work was generally regarded as the marvel of the match.

When Hazael, the Londoner of astonishing prowess, retired from the track at 11:37 last night, he had rolled up the enormous record of 540 miles in 120 hours. To his enthusiastic handlers in walker’s row he complained of feeling tired and sleepy. His limbs were sound and apparently tireless as steel. He partook heartily of nourishment and then, throwing himself on his couch, caught a few cat naps. At 1:49:20 he bounded out of his flower covered alcove, and once more took up the thread of his travels. His rest of two hours and twelve minutes had greatly improved him. He had been sponged and rubbed, and grinned all over his quaint face at his enormous score. That he was yet full of vigor and energy was apparent from the work he immediately entered upon. He had not walked more than half a lap when he gave a preliminary wobble. Then he clasped his hands over his ears, pulled his head down until his slender neck was well craned, and shot over the yellow pathway at a rattling pace. The sleepy watcher pricked up their ears at the shout which greeted this performance, and a fusillade of handclapping shook the garden. Fitzgerald was jogging over the tanbark at this time, sharply working to draw nearer to the Englishman’s figures on the scoring sheets. He accelerated his speed as the Londoner resumed the task before him. Within a few minutes both men were running like reindeer. It is doubtful they could have made better time if a pack of famished wolves had been at their heels. Volley after volley of applause thundered after them from the spectators. The runners kept close together. Between the hours of 2 and 8 o’clock this morning, so swift was their movements, that each man had added six miles and seven laps to his score or within one lap of seven miles. The struggle became so intense that the spectators began to realize that something unusual was in progress. A stir was apparent all over the vast interior and wearied humanity pushed itself to the rail to see what was going on.•

Aaron Burr, statesman and murderer, was, as Lin-Manuel Miranda describes him, the “damn fool” who shot Alexander Hamilton. Burr’s own death was less dramatic, though there was some small-scale intrigue which accompanied it.

Burr spent his last days reclusively on Staten Island, New York. He was a decidedly shadowy figure in the borough, and his funeral services were lightly attended. But there was one entrepreneur who kept a close check on the former Vice President during his waning moments. He had his reasons. An excerpt from an article in the September 8, 1895 New York Times:

It is not generally known that Aaron Burr spent the last days of his life and died on Staten Island. A few paces back from the Staten Island Ferry landing, at Port Richmond, stands the St. James Hotel, which is anything but a pretentious structure, and was originally a two-story boarding house in the year 1836, kept by a couple named Edgerton. It was during the early part of that year that Burr took a room there, and Mrs. Edgerton became his faithful servant and nurse. He sought seclusion and peace for his last days on earth, and, to an extent, found his desire within the great city of his choice, where he had realized the greatest triumphs of his life. The town was then composed of but a few scattered houses, and the Jersey shore was covered with a pine forest to the water’s edge, a clear view of which could be had from this old dwelling house. He rarely left his room, which was the front apartment on the second floor, now used as a parlor in the hotel. The furniture was antique and the room about eighteen feet square. The bed upon which Burr died was an old-fashioned, four-post, chintz-curtained one. Over the mantel now hangs a profile steel engraving of Burr, undoubtedly cut from some biography of the man, simply framed, to which, until recently, there was attached the inscription: ‘Aaron Burr died in this room Sept. 14, 1836.’

Upon rare occasions, and when he was confident that he would not be noticed, he wandered a short distance from his place of refuge, but the old man was too well known by the villagers to escape observation, and many eyes were upon him at every step, the villagers being proud of their visitor and observant of every action of so celebrated a man. He was an under-sized, sparsely built old man at this time, but he was also, to the end, erect and soldierly in bearing. His attire was always very fine, and he dressed with the utmost neatness, was quite the aristocratic gentleman of the old school, and the refinement and elegance of his manner were invariably conspicuous. He could be singularly winning and gentle even with the humblest. His complexion was pale and like parchment for years before his death, and at this time he was upward of eighty years of age. The dignity of his face was slightly marred by a thin, aquiline nose, which had a decided bend to one side, either through some accident or by nature’s malformation. Despite his advanced age, his eyes were keen and magnetic to a remarkable degree. He had learned or rather grown to dislike the curiosity seeker, and finding that he could not take his short walks abroad without being gazed at continually by the natives of Staten Island, he became more seclusive as the days went by, and finally refused to leave his room. In this room, rendered historic by his presence, this old decrepit, wornout, once great man passed his time with memories and sought consolation in the love letters of the women who had once loved him, among which were those of Mme. Jumel, filed with affectionate regard and regrets that a cruel fate had separated them. All those letters were scattered about his room, and when he died hundreds of such letters loose and in packages tied with ribbons were scattered upon his bed and upon the floor of the chamber. Among the evidences of his intriguing disposition, not at accusers, but as tokens of the loves of his victims, the old man breathed his last. …

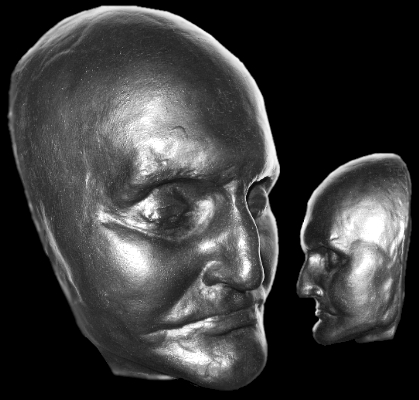

The old man had no attendant. He lived alone, with his old joys and his new sorrows, waiting for death to claim him and take him he knew and seemed to care not whither. A mysterious stranger haunted the house for many days and nights before the death of Burr. He never was admitted to the recluse, but always made interested inquiries concerning his health, and he was supposed to be either a relative or interested friend of the statesman, although he was neither. This man was faithful to the determination, and almost immediately after Aaron Burr’s death put in an appearance, and, without saying, “By your leave,” opened his satchel and proceeded, as if he had a right to do so, to take a plaster cast of the dead man.•

In the 1870s, a little more than a decade before the first of his two non-consecutive terms as U.S. President, Grover Cleveland acted as a hangman in New York State’s Erie County, making sure murderers received the drop. It’s not likely that Cleveland wore a hood since he was the sheriff and everyone knew he was performing the deed. From an article in the July 7, 1912 New York Times that recalls the Commander-in-Chief as an awkward, young executioner:

In the office of Sheriff of Erie County there has been for many years a Deputy Sheriff named Jacob Emerick. Mr. Cleveland’s predecessors had from time immemorial followed the custom of turning over to Emerick all of the details of public executions. So often had this veteran Deputy Sheriff officiated at hangings that he came to be publicly known as “Hangman Emerick.” Although a man of a rugged type and not oversensitive, Emerick after a while realized that this unfortunate appellation was seriously embarrassing to his family. Therefore a feeling of resentment began to grow within him.

During Cleveland’s term as Sheriff a young Irishman was convicted of the murder of his mother, and was sentenced to be hanged. The case of “Jack” Morrissey developed some features that excited widespread public interest and some sympathy for the convict. Efforts to obtain a pardon failed, however, and the final date of execution was fixed.

Then it was that Cleveland surprised the community and his friends by announcing that he personally would perform the act of Executioner. To the remonstrance of his friends he refused to listen, pointing to the letter of the law requiring the sheriff to “hang by the neck,” &c. He furthermore insisted that he had no moral right to impose upon a subordinate the obnoxious and degrading tasks that attached to his office. He considered it an important duty on his part to relieve Emerick as far as possible from the growing onus of his title of “Hangman.”

“Jake and his family,” said Mr. Cleveland, “have as much right to enjoy public respect as I have, and I am not going to add to the weight that has already brought him close to public execution.”

Thus it was Sheriff Cleveland, standing behind a screen, some twenty feet away from the law’s victim, pushed the lever that dropped the gallow’s trap upon which poor Morrissey stood.

A few Buffalo people still live who can bear out the statement that this little tragedy made Mr. Cleveland a sick man for several days thereafter. He was not so stolid and phlegmatic as very many persons have been told to believe.•

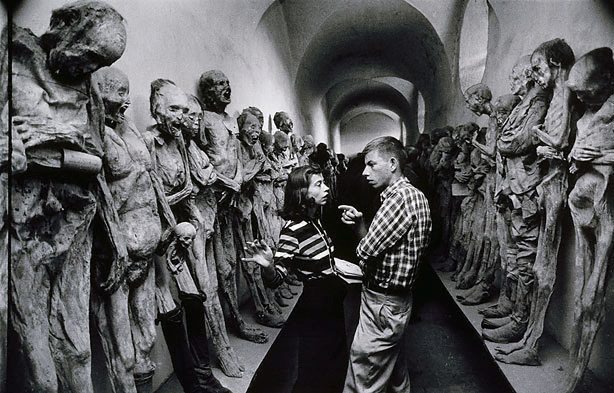

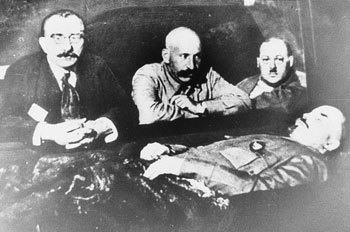

For better or worse, Vladimir Lenin was treated with a powerful embalming fluid when he succumbed in 1924, allowing his body to lay in state for the long-term. (His caretakers, by the way, drank some of the alcohol used in the process and got properly pissed.) It wasn’t an easy afterlife for the remains as they had to be spirited to Siberia during WWII to ensure the Nazis didn’t abscond with them. More than 145 years and many “touch-ups” later, the Bolshevik hero still looks swell.

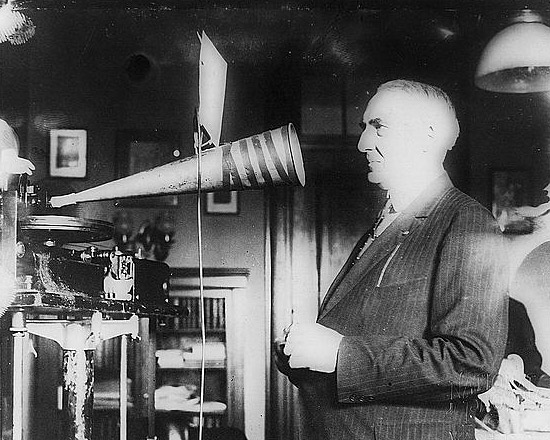

In 1931, the New York congressman-doctor-playwright William Irving Sirovich traveled to Europe and learned of a method for lasting post-life preservation. Upon his return, he suggested the United States use the treatment to follow the Soviet lead and hold onto its heroes long after their last breaths. Since it was just days after the passing of Thomas Edison, Sirovich hoped the inventor would be the first to be maintained in this manner. An article in the October 23, 1931 Brooklyn Daily Eagle had the story.

Tags: Thomas Edison, Vladimir Lenin, William Irving Sirovich

Tags: Pink Sessions

I don’t eat meat, but I don’t understand why people who do tend to recoil at horse flesh. No different than dining on pig, is it?

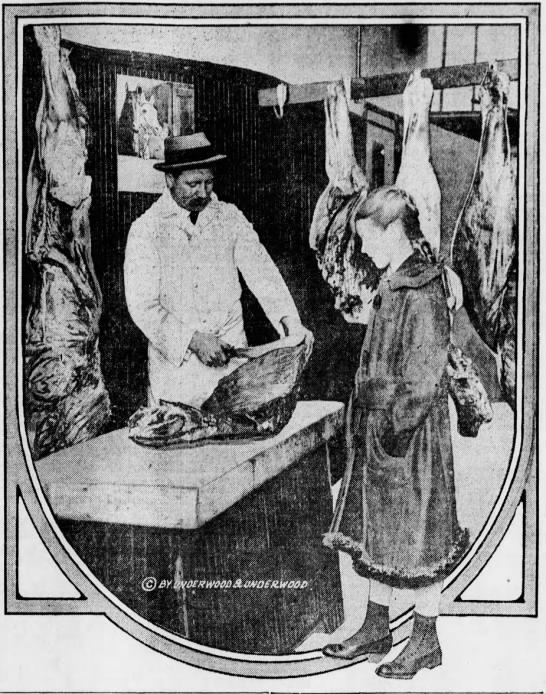

One immigrant in the early 1900s who had a dream of teaching America to love horse meat was John Sulser who opened what was reported to be the nation’s first all-equine butcher shop in Manhattan. For a little while at least, he enjoyed a thriving business. An extended report in the February 18, 1917 Brooklyn Daily Eagle tells his story. Read the opening below.

Tags: John Sulser

Tags: Thomas Sabin

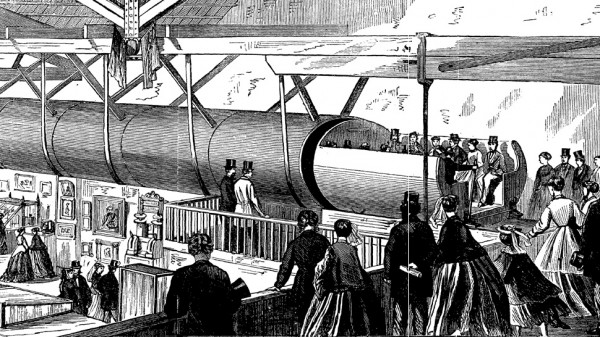

It wasn’t quite the Hyperloop, but some in the Victorian Era has an interest in utilizing pneumatic tubes to transport people. Such systems had successfully moved mail, with some foreseeing a day when there would be tubes conveying messages to every home. (The Internet, of course, ultimately did that idea considerably better.) But travel for humans was another order of difficulty. An article from the March 23, 1867 Brooklyn Daily Eagle hopefully addressed the topic.