August Engelhardt was at least sincere in his faith and in the observance of its tenets. For days he lived alone, eating nothing but bread fruit and cocoanuts, swimming in the sea or the still lagoon; studying in the fauna and flora of his island by day, or lying on the hot beach; by night sleeping in a hollow scooped out of the sand.

Occasionally he saw, or thought he saw, men moving in the cocoa groves, and once when he went to investigate he discovered for a certainty that he was not alone on the island. A number of lithe, naked, dark-skinned men and women ran hastily away. But the natives were few and harmless; apparently, too, they feared if they did not actually worship this great man with white skin and shaggy yellow hair who emerged glistening from the lagoon, or appeared suddenly in the cocoa groves. They kept away from him and were even more exclusive when his companions came.

It may be supposed that Engelhardt led a dreary life on Kahakua while awaiting the arrival of his disciples, but if one may judge the student’s temperament from his acts it seems more likely that this was the happiest period of his existence on the atoll. He had left the world behind him; he was free. Of the food of his choice he lacked none, and the balmy air of the Pacific, the warm sun of the tropics, and the cool spray of the ‘combers’ were his playthings. At dawn the nature feasted upon his eyes with beauty as the sun, his god, climbed over the horizon, tinted the palm crests with gold, the sea with amber and opal and crimson, and bathed the kneeling figure on the beach with a mantle that was his inspiration. By day Engelhardt’s joy was that of a dream realized. At sunset the lagoon clasped his god in a broil of molten lava; then came the night, with the great dome of stars, the breeze rustling though the cocoa fronds, and the Pacific chanting like a great organ, lulling him to sleep.

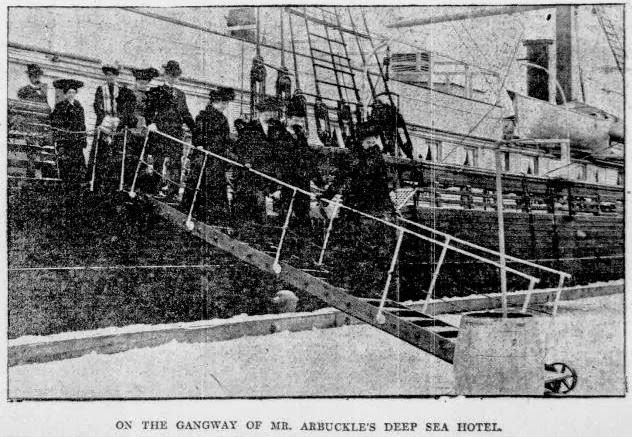

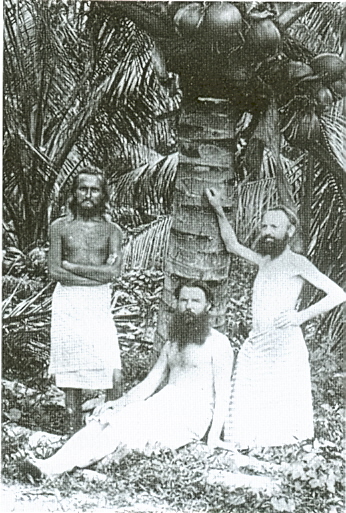

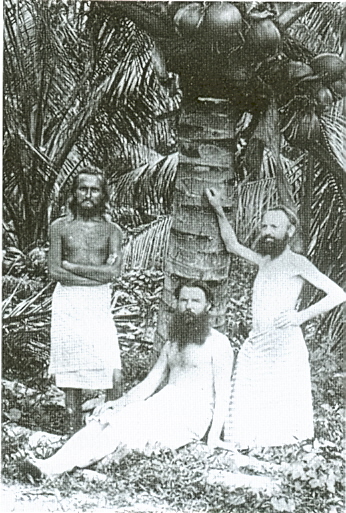

But there was an end to this, and a beginning to disillusion. The vessel which was to have brought his converts dropped anchor in the lagoon. A boat came ashore with four men in it, two of them sailors, the other two Engelhardt’s staunchest disciples. They were Max Lutzow, at one time director of the well-known Orchestra of Berlin, and Heinrich Eukens, a student of Bavaria and a native of Heligoland. The other converts, upon the departure of Engelhardt and his eloquence, had received the attention of other sects, and been convinced that Kahakua was full of cannibals, sweltering with fever miasma; in brief, that Engelhardt was leading them to death.

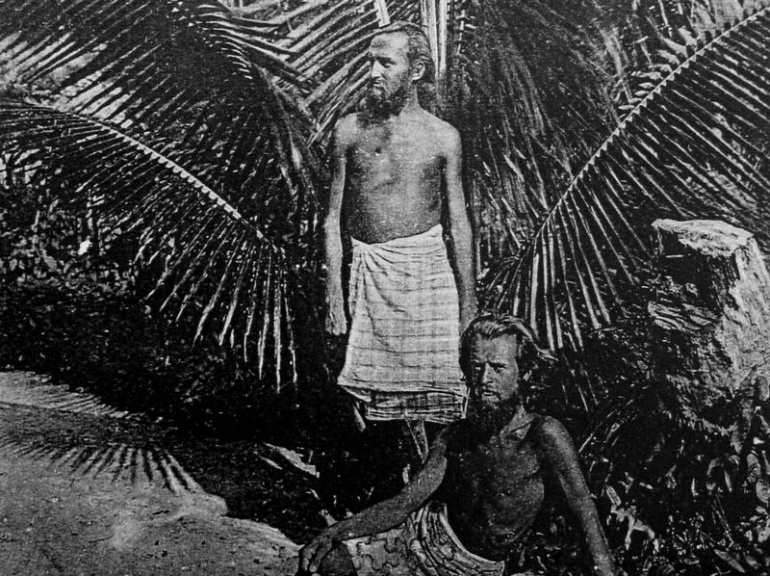

It was a great blow to Engelhardt, but the die had been cast. The vessel sailed away, and he, with Lutzow and Eukens, was left on the island. The two new arrivals were delighted with the appearance of Engelhardt. Weeks of life under the sun, in the salt sea, and living upon fruit, had brought him to a state of wonderful physical perfection. His skin was like copper and against it his yellow hair shone like gold. The two disciples immediately joined him in his method of living. For days theirs was an idyllic state, and they were contented. But an end came. The sudden change had been too much for the less-rugged constitution of Eukens, who contracted a cold, developed fever, and died quite suddenly. He had been given no remedies, as it was contrary to the faith of the sun worshippers.

His companions buried him in the sand. For days they wandered listlessly about the island, the spell of which had been broken. But at length they realized that such an undertaking could not be expected to succeed without suffering.

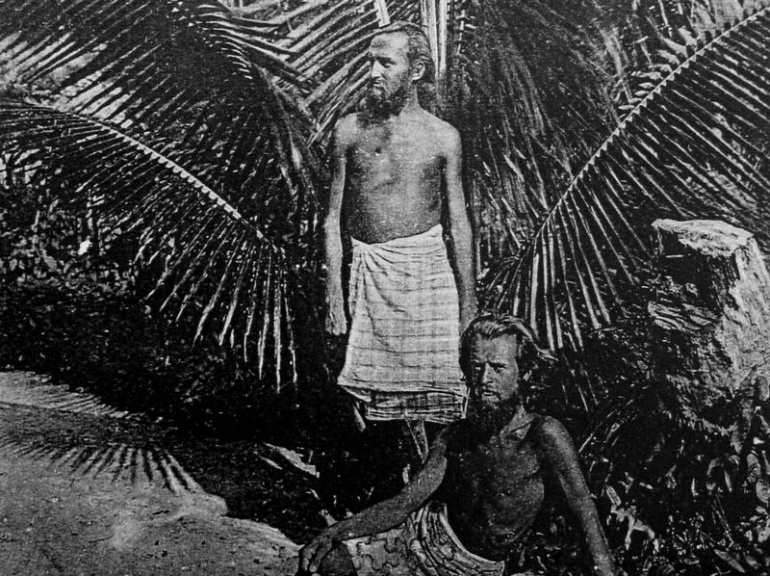

They began again, and things went well, although the gloom attending the death of Eukens never left them. Lutzow, the musician, developed the physical strength which characterized Engelhardt. For a year the two men lived comparatively happily, except for one thing, which is the one ray of humor in the whole history.

It was understood that the world of civilization–art, letters, dress, and diet–had been forgotten, but the genius of Lutzow was something which was all Lutzow and nothing of Engelhardt. Lutzow and his music could not be separated. Donizetti was his favorite, although the long hours of the idle day he did not forget passages from Wagner, Verdi, Mascagni, Bach, Liszt, Beethoven, and others. Engelhardt loved music, but he had a particular aversion to Donizetti and a positive horror of Bizet, who was associated in his mind with “Carmen,” who in turn was the bête noir of his faith.

Engelhardt tolerated the music as long as he could; then, unable to associate with a human musical, he quarreled with Lutzow. It was a bitter quarrel, for the student had hurt the musician to the quick. Eventually the two men became so estranged that Lutzow applied one night for permission to sleep away from the island on the Wesleyan mission cutter from Ulu, which was in the lagoon.

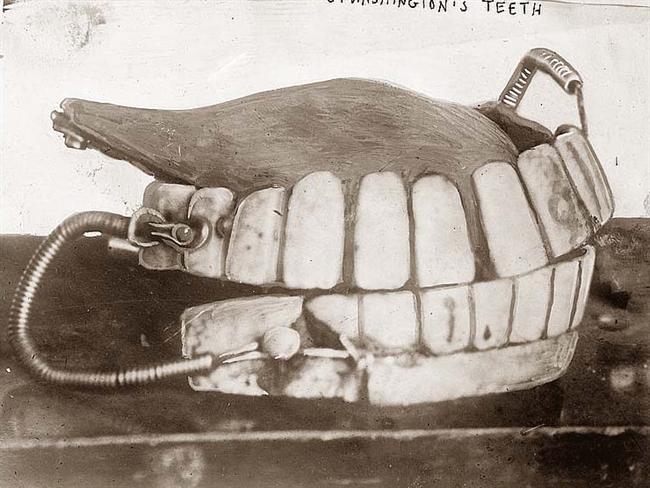

That night the cutter dragged her moorings and was carried on the tide through the narrows to the open sea. Cross-currents prevented the craft from pulling back for two days, during which Lutzow still observant of the sun-worshippers’ faith, refused to take shelter, and also refused all nourishment that was not fruit. There was no fresh fruit on board, consequently he starved. He lay upon the deck of the cutter, too, for two days and two nights, exposed to a cold, wet wind. Shorty after the cutter put back into the lagoon the musician developed a high temperature. He grew worse, lingered for a week, then died.

He was buried in the sand by Engelhardt beside the unfortunate Eukens. The Wesleyan missionaries offered to take Engelhardt back to civilization. He flew into a rage, said he owned the island, and forbade them ever to drop anchor in the lagoon of Kahakua again.

So the cutter sailed away to Ulu and Engelhardt was left alone in the Palm Temple. For nearly two years more he continued to live the ‘pure, natural life,’ but the charm had been completely broken by the death of his two disciples.

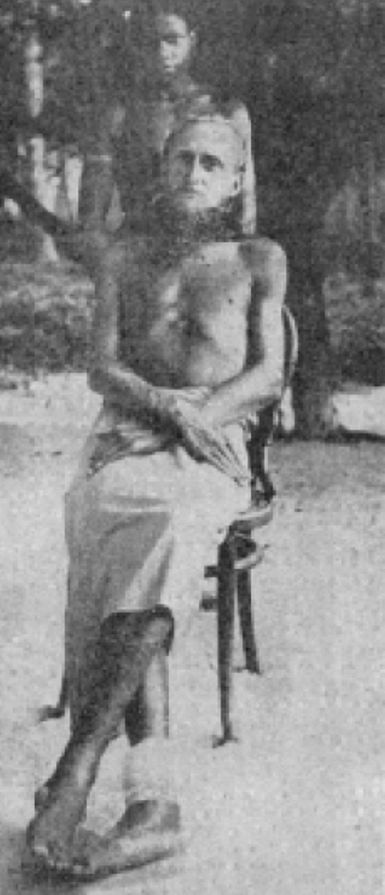

Then in 1903 came a drought which reduced the fruit crop. The little left of it was wiped out in the Spring of 1904 by a storm. Engelhardt had the alternative of casting in his lot with the natives and eating hogflesh, or sending a request for succor to Ulu or Herbertshohe. He did neither in his stubborness, and starvation and thirst did their work.

One day a canoe paddled into Herbertshohe, driven by two natives who said the white man was sick and possessed of devils; wandering about Kahakua preaching his doctrine to the trees and frightening the natives. Would the German officials please come and take him away?

Engelhardt refused all nourishment to the last, refused all medicine, and accused the missionary of interfering with his convictions. He wrought himself up to a great frenzy, fell upon the deck, and was restrained only with difficulty from flinging himself overboard and swimming back to his island. Before the beach had sunk below the horizon the man was dead. Then the launch put back.

Wrapped in a German flag, August Engelhardt, founder and last survivor of the sun worshippers, was laid to rest beside Lutzow and Eukens on the beach at Kahakua.”•