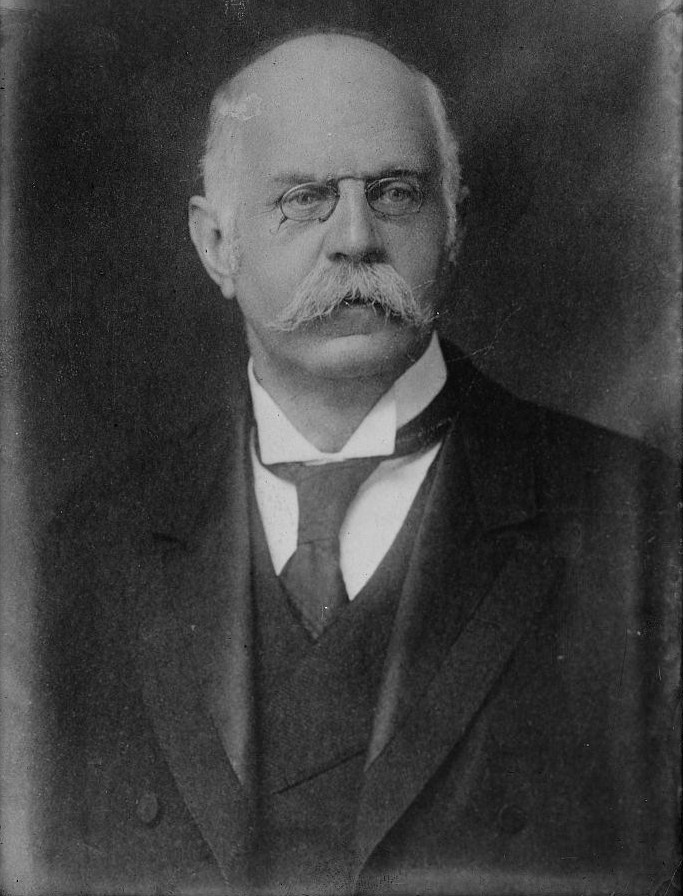

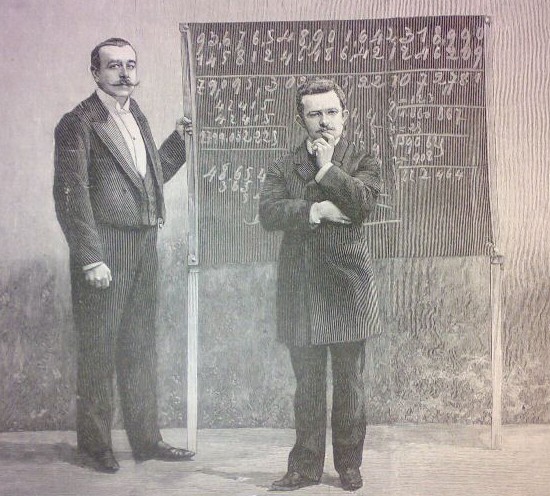

During his lifetime, Leonard Darwin never intended to be a monster.

A son of Charles, Leonard was a staunch supporter of eugenics whose ideas about race, class, criminology, etc., were not just morally reprehensible but also scientifically ignorant. He was really a one-man cautionary tale for how highly respectable people can spout dumb and dangerous hogwash. A 1912 New York Times article reported on a speech he delivered, in which the eugenicist proposed experimenting with X-ray sterilizations and segregating the indolent and anyone else he deemed an enemy of moral progress. The opening:

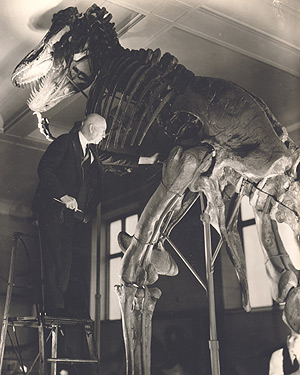

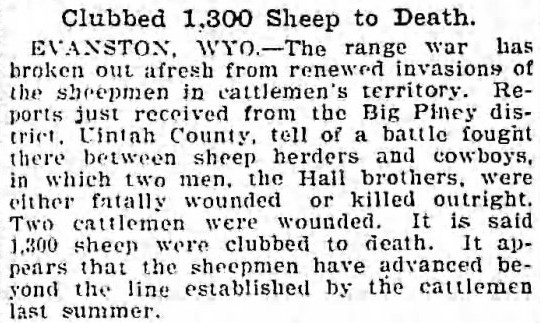

Practical measures advocated by some students to improve races, such as the sterilization of criminals by the X-ray, the promotion of larger families among those of good stock and limitation among others, were discussed at yesterday’s session of the International Congress of Eugenics in the American Museum of Natural History.

Major Leonard Darwin, a son of the author of The Descent of Man, urged the experimental use of the X-ray, with the consent of the subject, to prevent descendants from the feeble-minded and habitual criminals. He suggested segregation for the wastrel, the habitual drunkard and “the work-shy” to prevent the transmission of their traits to future generations.

Major Darwin also urged that the sound and fit and superior people should, by a campaign of patriotism, be induced to raise larger families. Racial deterioration seems evident among all highly civilized peoples, he said, because of the thinning out of the descendants of highly endowed stock and the multiplication of those inferior endowment.

“The result is anticipated,” he said, “that in comparison with the ill-endowed, the naturally well-endowed will, as time goes on, take a smaller and smaller part in the production of the coming generations, with a tendency to progressive racial deterioration s an inevitable consequence. And if we ask whether existing facts confirm or refute this dismal forecast, what do we find? Statistical inquiries, at all events, prove conclusively that, where good incomes are being earned, there the families are on the average small.”

History taught, he said, that races in the past had fallen from high estate because of the progressive elimination of their best types.

“I can find no facts,” he continued, “which refute the theoretical conclusion the the inborn qualities of civilized communities are deteriorating, and the process will inevitably lead in time to an all-around downward movement.”

The only efficient corrective which Major Darwin could think of, he said, was an appeal to patriotism.

Unpatriot to Limit Some Families

“What is necessary is to make it deeply and widely felt that it is both immoral and unpatriotic for couples sound in mind and body to unduly limit the size of their families,” he added.

Major Darwin read this sentence slowly, and at the request of two or three in the audience, read it over again. He said that he believed such a campaign would succeed, when persons of character and good endowment were awakened to the danger threatening their race.

“The nation that wins in this moral campaign,” he said, “will have gone half-way toward gaining a great racial victory.”•