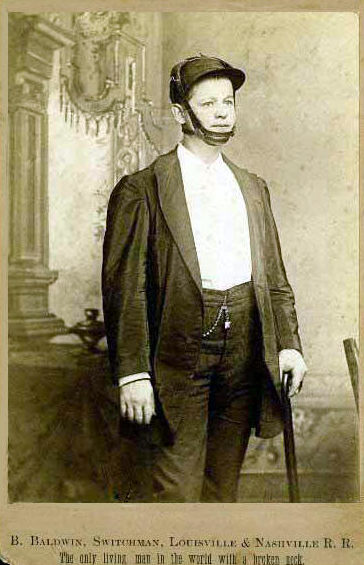

From the September 28, 1891 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

You are currently browsing the archive for the Photography category.

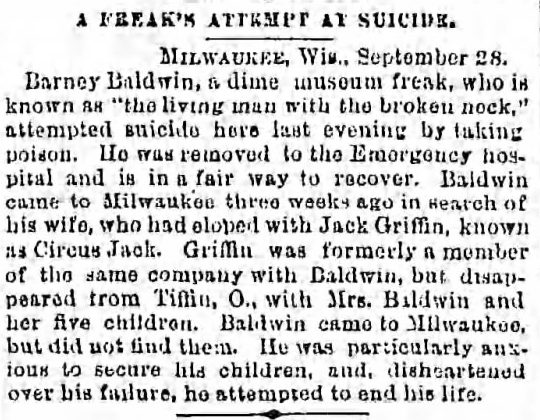

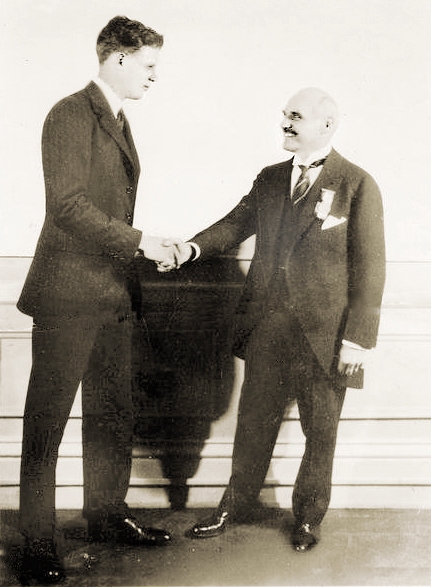

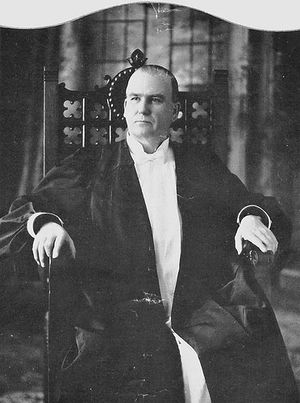

In 1919, New York City immigrant hotelier and restaurateur Raymond Orteig had an inspiring if dangerous idea to speed up the development of aviation. He established a $25,000 prize to go to the first pilot to complete a successful solo flight between New York and Paris. The businessman received a great return on his investment as numerous aviators individually poured time and resources into the endeavor. The first six attempts ended in failure and death, before Charles Lindbergh collected the check from Orteig, who had flown to Paris for the occasion.

I was reminded of Orteig by a recent Vivek Wadhwa column in the Washington Post which compared him to Peter Diamandis, who 20 years ago established the $10,000,000 X Prize to similarly stimulate space travel. Below is a Brooklyn Daily Eagle feature published a few months after Lindbergh’s 1927 triumph, which told of Orteig’s unlikely rags-to-riches story and how he sparked one of history’s great moments.

Tags: Charles Lindbergh, Peter Diamandis, Raymond Orteig, Vivek Wadhwa

It surprises me that most of us usually think things are worse than they are in the big picture, because we’re awfully good at selective amnesia when it comes to our own lives. Homes in NYC that were demolished by Hurricane Sandy are mostly valued more highly now than right before that disaster, even though they’re located in the exact some lots near the ever-rising sea levels, in the belly of the beast. The buyers are no different than the rest of us who conveniently forget about investment bubbles that went bust and life choices that laid us low. When it comes to our own plans, we can wave away history as a fluke that wouldn’t dare interfere.

When we consider the direction of our nation, however, we often believe hell awaits our handbasket. Why? Maybe because down deep we’re suspicious about the collective, that anything so unwieldy can ever end up well, so we surrender to both recency and confirmations biases, which skew the way we view today and tomorrow.

While I don’t believe the endless flow of information has made us more informed, it is true that by many measures we’re in better shape now than humans ever have been. On that topic, the Economist reviews Johan Norberg’s glass-half-full title, Progress: Ten Reasons to Look Forward to the Future. The opening:

HUMANS are a gloomy species. Some 71% of Britons think the world is getting worse; only 5% think it is improving. Asked whether global poverty had fallen by half, doubled or remained the same in the past 20 years, only 5% of Americans answered correctly that it had fallen by half. This is not simple ignorance, observes Johan Norberg, a Swedish economic historian and the author of a new book called “Progress”. By guessing randomly, a chimpanzee would pick the right answer (out of three choices) far more often.

People are predisposed to think that things are worse than they are, and they overestimate the likelihood of calamity. This is because they rely not on data, but on how easy it is to recall an example. And bad things are more memorable. The media amplify this distortion. Famines, earthquakes and beheadings all make gripping headlines; “40m Planes Landed Safely Last Year” does not.

Pessimism has political consequences. Voters who think things were better in the past are more likely to demand that governments turn back the clock. A whopping 81% of Donald Trump’s supporters think life has grown worse in the past 50 years. Among Britons who voted to leave the European Union, 61% believe that most children will be worse off than their parents. Those who voted against Brexit tend to believe the opposite.

Mr Norberg unleashes a tornado of evidence that life is, in fact, getting better.•

Tags: Johan Norberg

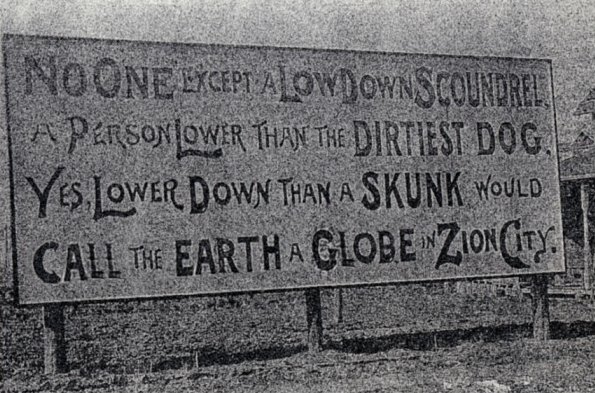

As long as the Earth is around, they’ll be those who wrongly argue that it’s flat.

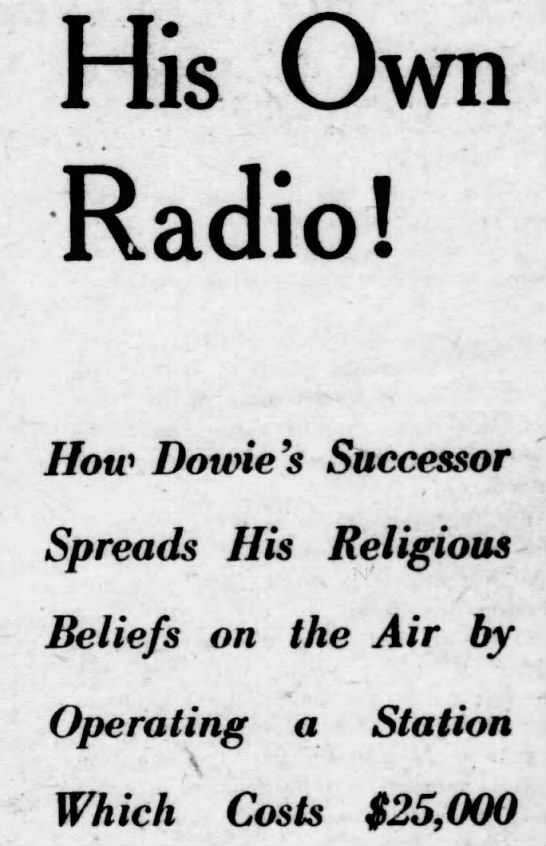

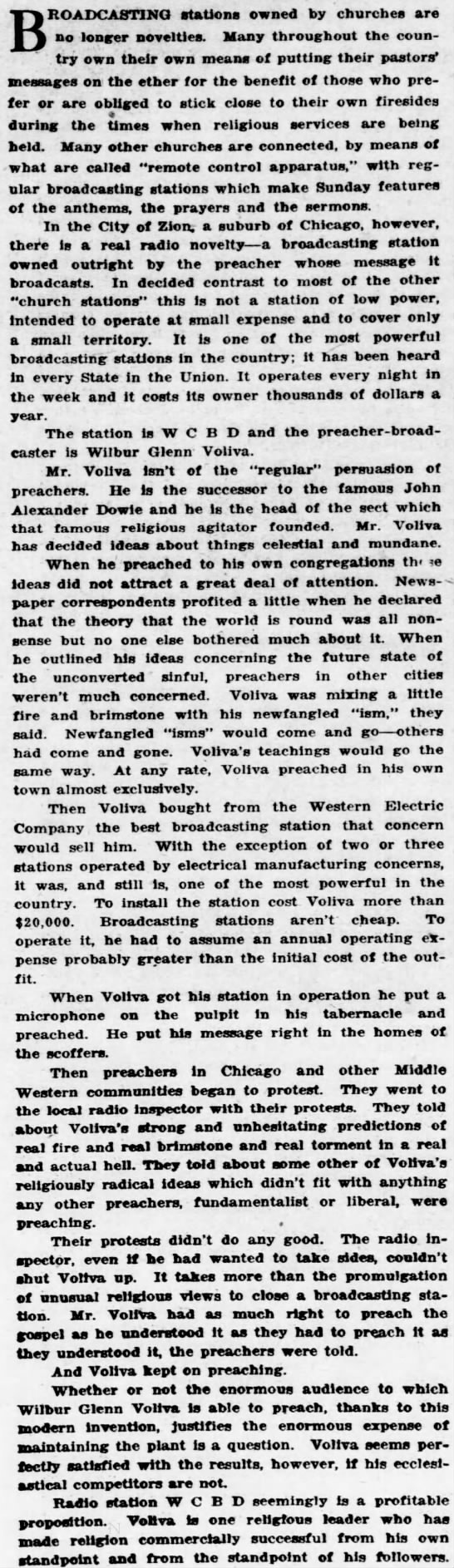

Few did so more vehemently than evangelist Wilbur Glenn Voliva, one of the most famous advocates of Flat Earth theories in America during the first half of the 20th century. In 1906, the preacher gained power over the Christian Catholic Apostolic Church in Zion, Illinois. He turned the community of 6,000 into a multi-pronged industrial concern, taking advantage of the very low wages he paid members of his flock. By the 1920s, Voliva owned one of the most powerful radio stations in the nation from which to preach his anti-science views, a forerunner of the many dicey religious figures to come who would mix mass and media.

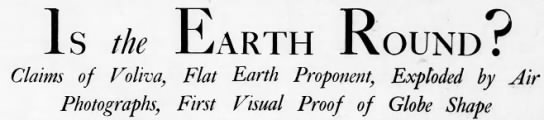

While Voliva despised globes, it was the advent of aerial photography (and his own outsize financial improprieties) that dimmed but did not end his career. After all, despite any proof, some still see what they want to see.

Three articles below from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle follow the arc of his notable life.

From June 22, 1924:

From April 19, 1931:

From October 12, 1942:

Tags: Wilbur Glenn Voliva

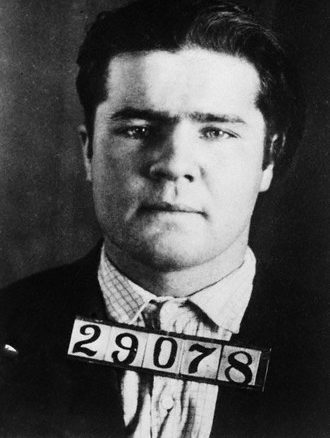

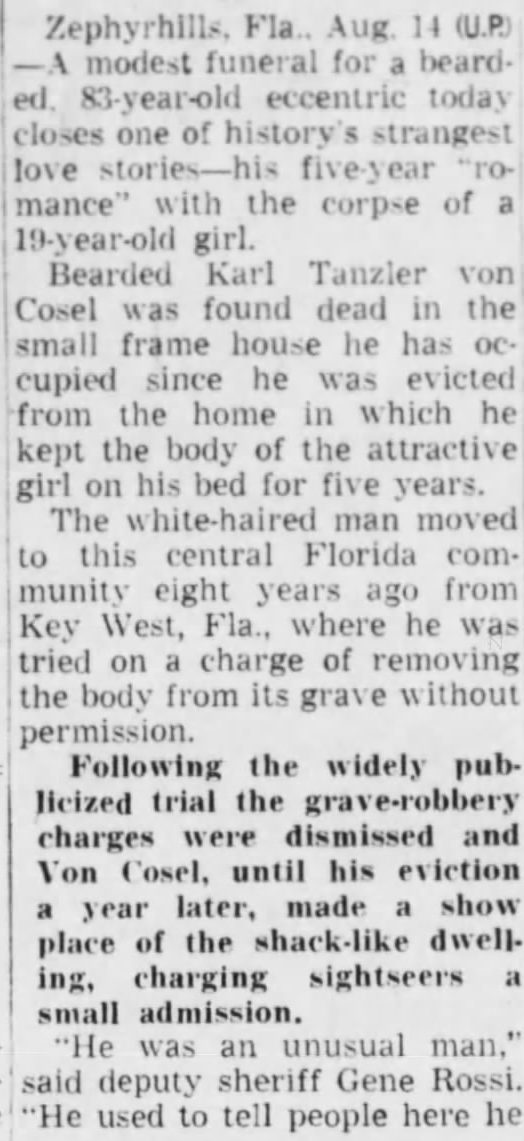

Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd was more famous than infamous, which seems a strange thing.

During the 1930s, the soft-featured felon participated in a string of brazen bank robberies and left behind a body count, but such was the hatred for financial institutions in America during the Great Depression that he was widely considered a Robin Hood if not a saint. Stories circulated that he shredded mortgages of down-and-out farmers while emptying safes and shared his ill-gotten gains with the hungry and disheartened, which was nearly everyone.

Who knows? Maybe he found time for such acts of benevolence in between shootouts and jail breaks, but these legends had more to do with what a desperate people needed than what a lone gunman was delivering. It was Woody Guthrie who put it all in perspective in his great song named after the beloved criminal, writing “Yes, as through this world I’ve wandered / I’ve seen lots of funny men / Some will rob you with a six-gun / And some with a fountain pen.”

Two Brooklyn Daily Eagle articles from 1934 recall Floyd’s wide renown at the end of his wild run.

From October 23, 1934:

From October 29, 1934:

A century ago in France it might have been as apt to refer to Georges Claude as a luminary as anyone else. The inventor of neon lights, which debuted at the Paris Motor Show of 1910, the scientist was often thought of as a “French Edison,” a visionary who shined his brilliance on the world. Problem was, there was a dark side: a Royalist who disliked democracy, Claude eagerly collaborated with the Nazis during the Occupation and was arrested once Hitler was defeated. He spent six years in prison, though he was ultimately cleared of the most serious charge of having invented the V-1 flying bomb for the Axis. Two articles below from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle chronicle his rise and fall.

From February 25, 1931:

From September 20, 1944:

Tags: Georges Claude

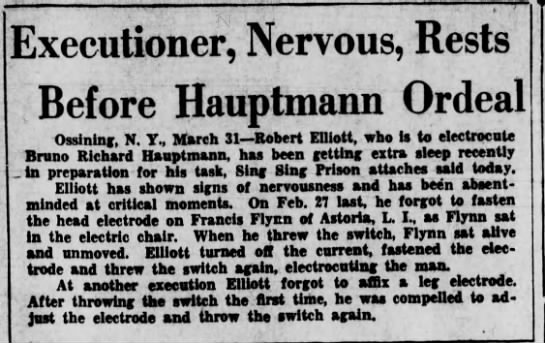

Bruno Hauptmann’s executioner, Robert G. Elliott, became increasingly anxious as the fateful hour neared, and you could hardly blame him. Who knows what actually happened to the Lindbergh baby, but the circumstances were crazy, with actual evidence intermingling with that appeared to be the doctored kind. To this day, historians and scholars still argue the merits of Hauptmann’s conviction. Elliot who’d also executed Sacco & Vanzetti and Ruth Snyder, was no stranger to high-profile cases, but the Lindbergh case may still be the most sensational in American history, more than Stanford White’s murder or O.J. Simpson’s race-infused trial.

Elliott, whose title was the relatively benign “State Electrician” of New York had succeeded in the position John W. Hulbert, who was so troubled by his job and fears of retaliation, he committed suicide. Elliott, who came to be known as the “humane executioner” for devising a system that minimized pain, was said to be a pillar of the community who loved children and reading detective stories. A friend of his explained the Elliott’s general philosophy regarding the lethal work in a March 31, 1936 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article, just days before Hauptmann’s demise: “It is repulsive to him to have to execute a woman, but he feels that, after all, he’s just a machine.” Such rationalizations were necessary since Elliott claimed to be fiercely opposed to capital punishment, believing the killings accomplished nothing.

Tags: Bruno Hauptmann, Robert G. Elliott

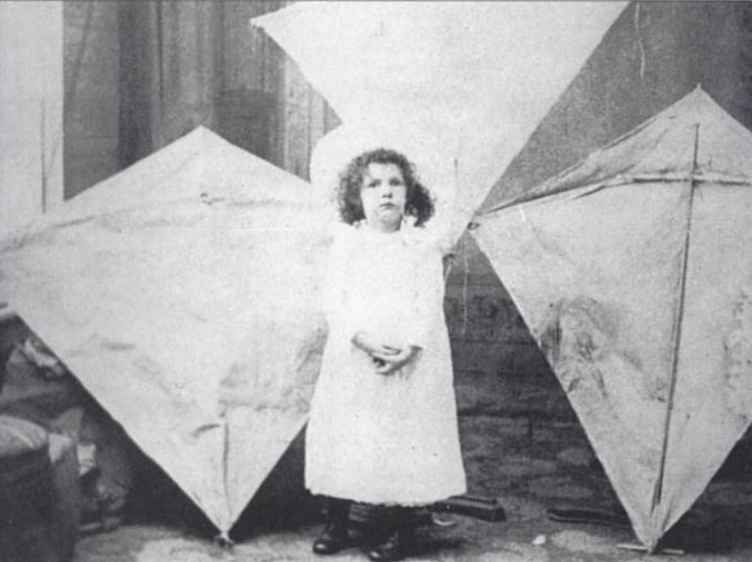

As drones are set to proliferate, being utilized to photograph and monitor and deliver, it’s worth remembering that kites were formerly dispatched to do some of the same duties, if in a much lower-tech way.

The first use of kites for scientific purposes dates back to 1749 and the meteorological experiments of Alexander Wilson, which occurred three years before Benjamin Franklin’s electrifying discoveries. The use of kites in science received a major boost in the second half of the 19th century, when New York journalist William Abner Eddy designed a superior diamond-shaped kite, which enjoyed improved stability and reached great heights, enabling him to take the first aerial photography in the Western hemisphere. Five years after that feat, in a 1900 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article, Eddy speaks of his plans for his airborne innovations, though the piece was abruptly cut off near the end by typesetters.

Tags: William Abner Eddy

“He that fights and runs away, may turn and fight another day; But he that is in battle slain, will never rise to fight again,” recorded the Roman historian Tacitus, though the original coiner of the phrase is unknown. It’s another way of saying: Honor is great, but it can get you killed.

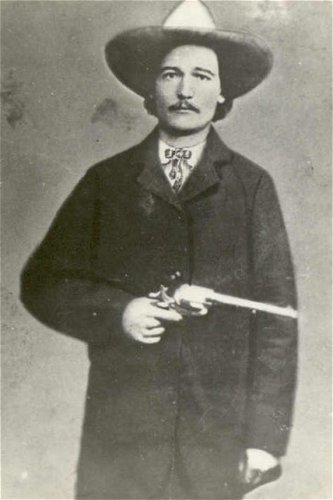

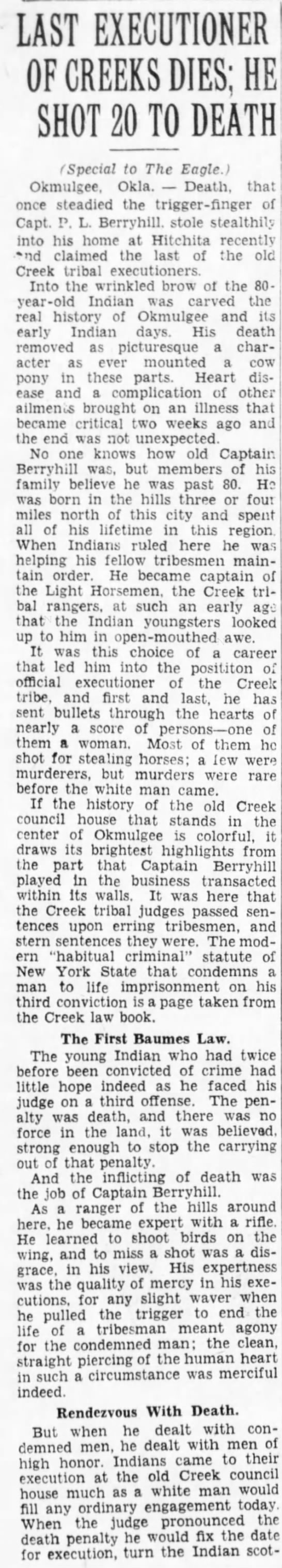

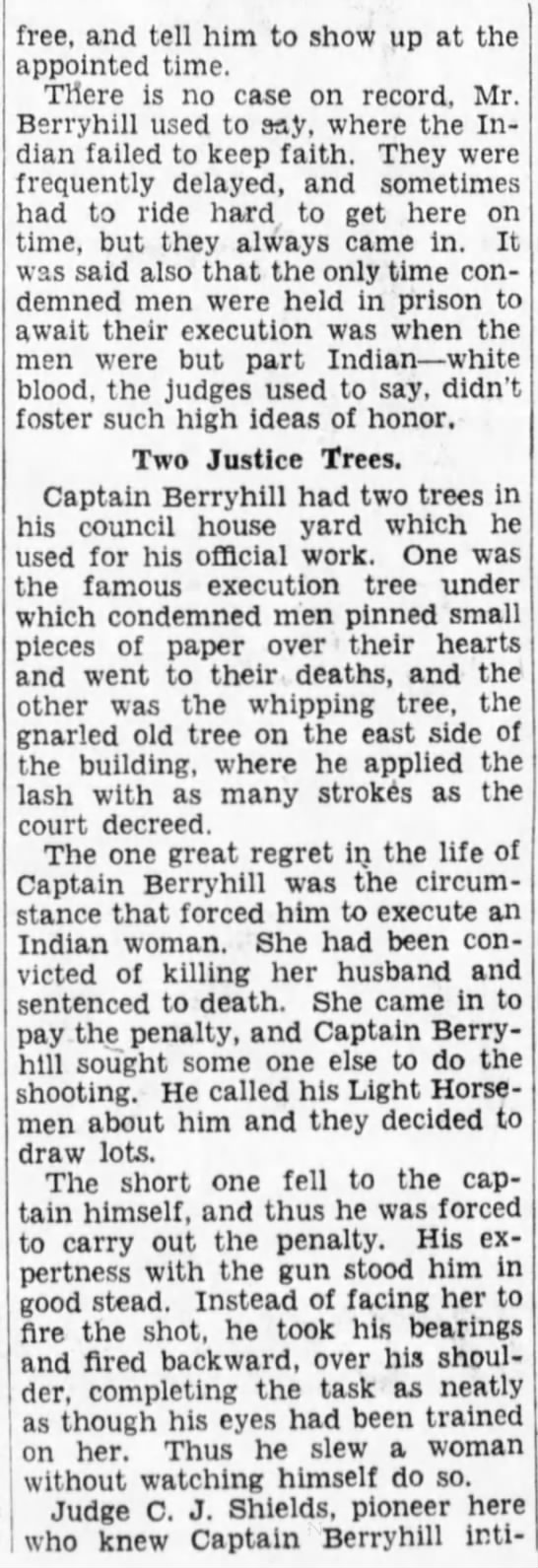

The 1929 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article below records the death of the Creek Nation’s Captain Pleasant Luther “Duke” Berryhill, who somehow balanced the disparate professions of Methodist minister and tribal executioner. He would preach to all who would listen and flog and shoot those who he was ordered to. Berryhill clearly believed in a retributive god.

One interesting note contained in the piece is that those Creeks condemned to die weren’t imprisoned nor were they escorted by authorities to the place of their execution on the fateful day. They were honorable men (and, occasionally, women) and reported dutifully for a bullet to the heart. They probably should have headed for the hills, honor be damned.

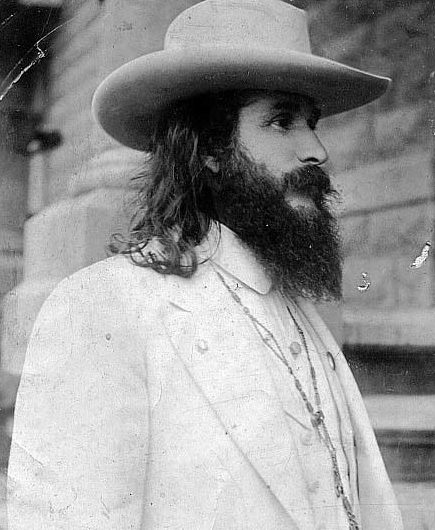

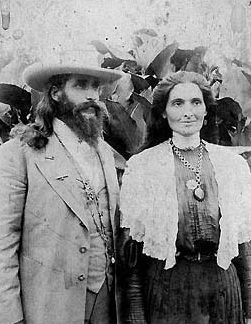

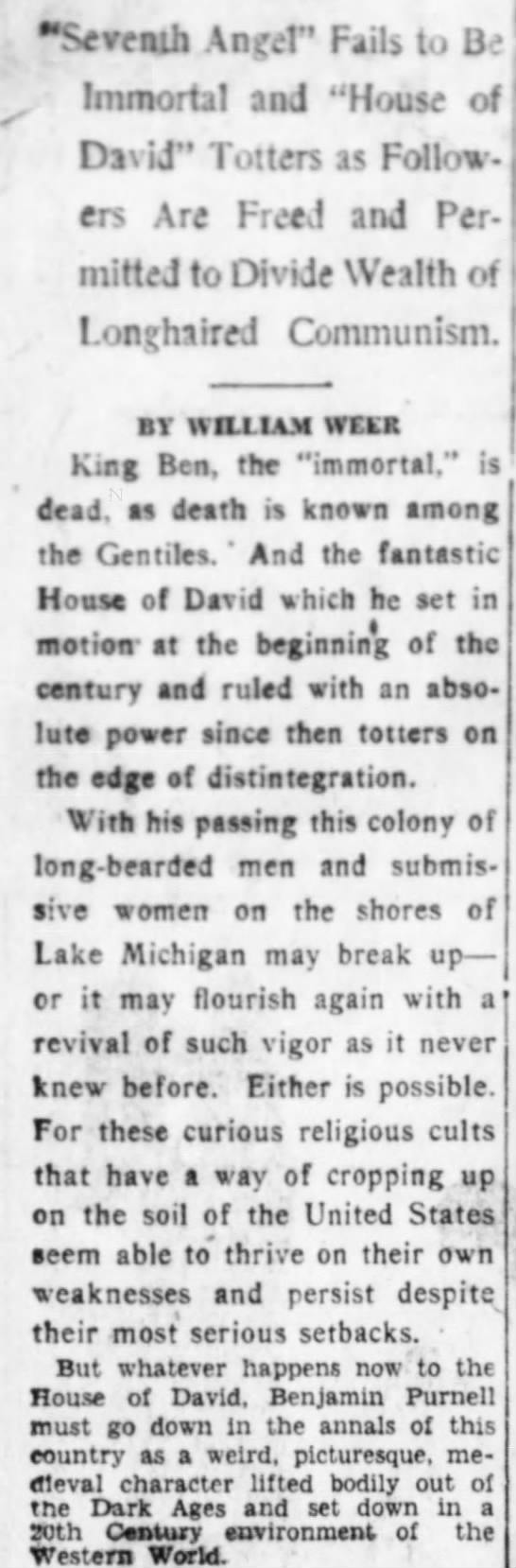

As his sprawling 1927 Brooklyn Daily Eagle obituary put it, cult leader Benjamin Purnell had “executive ability.”

He used native business acumen to escape an impoverished youth in Kentucky through the establishment, in 1903, of a religious cult known as the House of David, which he cofounded with his wife, Mary. They claimed to be the final representatives of God who would be sent to Earth.

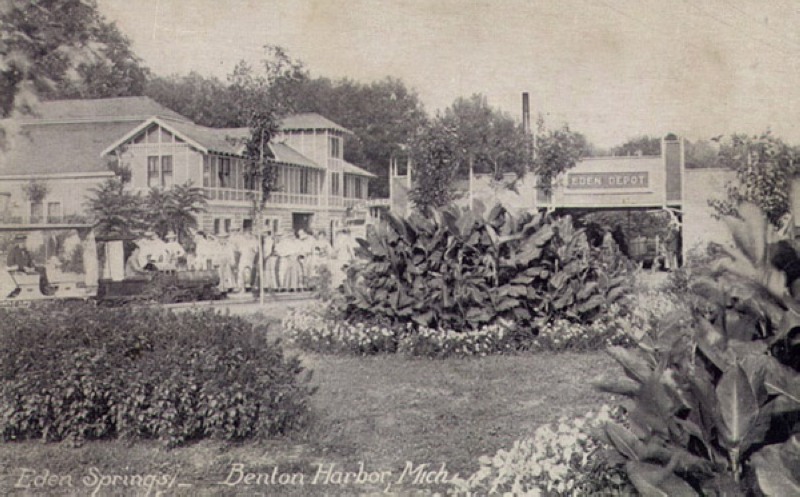

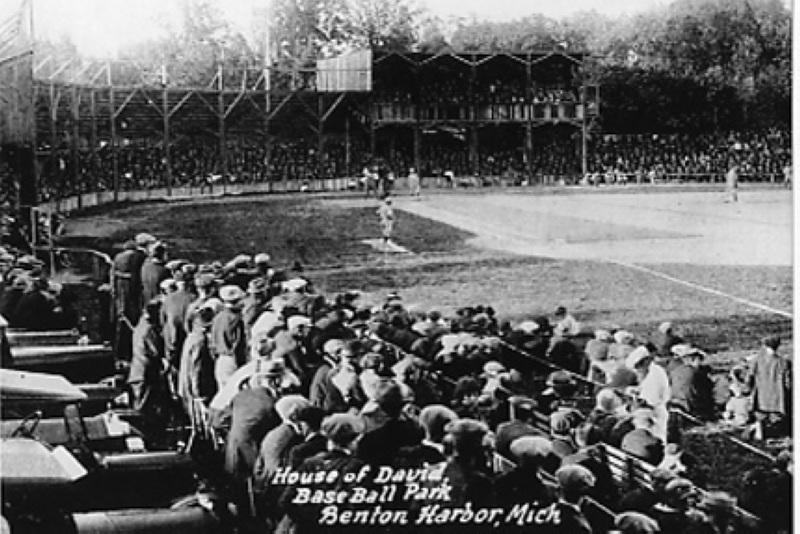

“King Ben,” as he came to be known, built a veritable empire of a commune, which bore fruit literally and figuratively, burnishing his brand by portraying himself as immortal and promising to confer everlasting life unto others who gifted him with their worldly possessions. It worked wonderfully well for a while. The community boasted a cannery, an electricity plant, bands, orchestras, a zoological garden and a barnstorming baseball team of wide repute.

By his last decade, though, Purnell was accused of having sex with numerous underaged girls who lived on the grounds and was also beset by other legal issues. As a royal, priest and CEO, his career was in tatters. He died soon after his fall from grace, mortal as the rest of us, with some followers splintering into smaller groups.

The obit’s opening is embedded below.

Tags: Benjamin Purnell, Mary Purnell

Jeannette Piccard, bold balloonist, is pictured directly above with her husband, Jean, and Henry Ford, the anti-Semitic automaker on hand to wish them–and their pet turtle–well on a daring 1934 trip via gondola into the stratosphere, which turned out to be a bumpy ride. Jeanette is usually credited as the first woman in space; her spouse was the twin brother of Auguste Piccard, the family’s most famous aeronaut. (The siblings would decades later inspire the name of Patrick Stewart’s Star Trek captain.) Jeannette traveled far not only up there, but also in here, following up her aviation exploits and a stint at NASA by being ordained an Episcopalian priest. An article in the October 23 Brooklyn Daily Eagle recorded the fraught moment when she reached the high point of her life, literally at least.

It almost never ends well for a demagogue nor for the demagogue’s people. Fascists are merely vulgar clowns until they’re in a position to do grave damage.

Was reading a passage from a 1925 article that ran in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle which begins this way: “Benito Mussolini is a fascinating character.” The writer wonders why Il Duce’s insane utterings demand rapt attention when others making similar statements would be jeered from the stage. That thought, of course, brings to mind the odious campaign of Donald Trump, a deeply wounded man who works a room like Torquemada as a Reality TV host.

James Baker has asserted he’s unafraid of a Trump Presidency, our checks and balances there to restrain his worst impulses. But a sick, authoritarian mind even scribbling in the margins of the Constitution could wreak havoc. The scariest part of the report below is that it argued the Italian dictator was already in steep decline, but just think how much suffering he caused before ultimately meeting the business end of a meat hook.

Tags: Benito Mussolini, Donald Trump

May Otis Blackburn may not have been the first Los Angeles cult leader, but she did do her voodoo several decades before Krishna Venta, L. Ron Hubbard or Charles Manson. Unsurprisingly, it did not end well.

“The Divine Order of the Royal Arms of the Great Eleven” (aka “The Blackburn Cult”) was established in 1922, after the “Queen and High Priestess” claimed the angels Gabriel and Michael were communicating divine messages to her and her daughter, Ruth Wieland Rizzio. They were assigned to write a book dictated to them by the angels, the publication of which somehow leading to the apocalypse.

Before the decade was through, the group was linked to animal sacrifices, sex scandals, an attempted resurrection of a deceased teen girl, poisonings and a follower being baked to death in a brick oven. When Blackburn was found guilty of grand larceny in 1930, the cult lost its agency. An article in the October 11, 1929 Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported on the grisly undertakings.

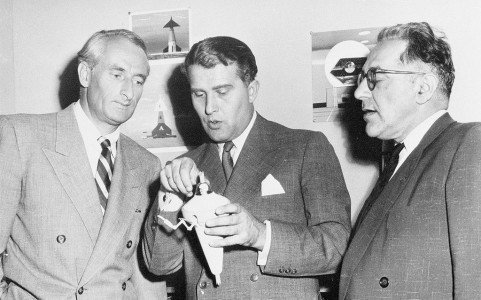

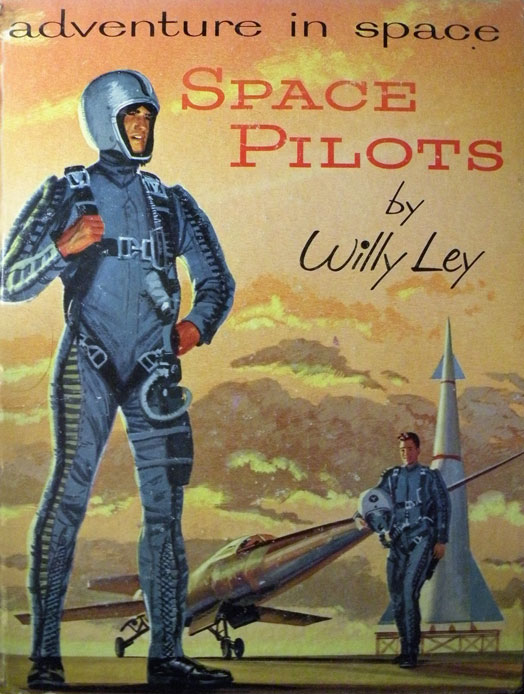

The top photograph offers an odd juxtaposition: That’s Wernher von Braun, a rocketeer who was a hands-on part of Hitler’s mad plan, whose horrid past was whitewashed by the U.S. government (here and here) because he could help America get a man on the moon; and Willy Ley, a German science writer and space-travel visionary who fled the Third Reich in 1935.

A cosmopolitan in an age before globalization, Ley only wanted to share science around the world and encourage humans into space and onto the moon. He knew early on Nazism was madness leading to mass graves, not space stations. When Ley arrived in America for a supposed seven-month visit by using falsified documents to escape Germany, he worked a bit on an odd rocket-related program: Ley led an effort to use missiles to deliver mail. It was a long way to go to get postcards from point A to point B, and an early attempt failed much to the chagrin of Ley, who donned a spiffy asbestos suit for the blast-off. An article on the plan’s genesis ran in the February 21, 1935 Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

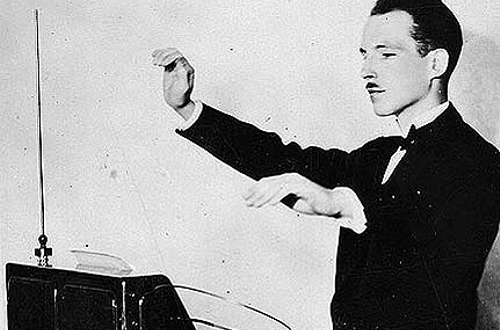

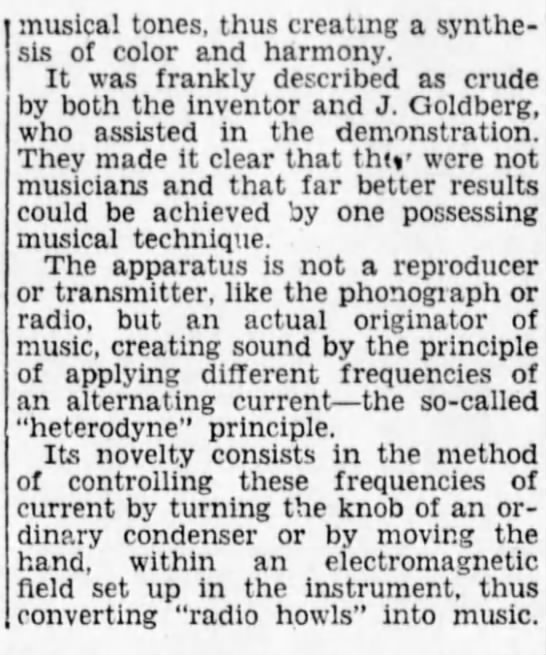

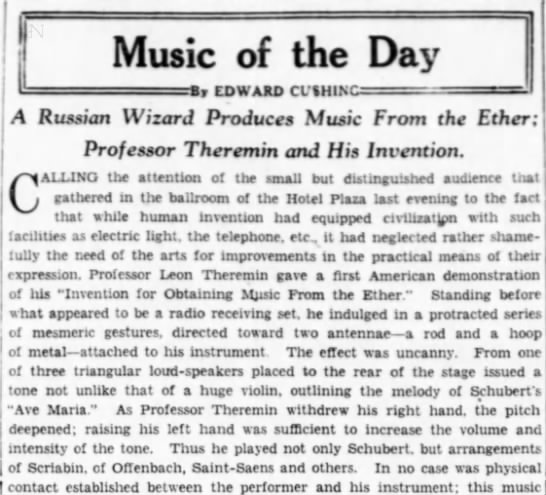

Leon Theremin, who died in 1993 at age 97, was most famously the creator of an electronic instrument in the 1920s that seemingly stole music from the air. Considered the Russian counterpart to Thomas Edison for his innovations in sound and video, he also created ingenious spying devices for the Soviet Union when he returned to his homeland–perhaps he was kidnapped by KGB agents but probably not–after a decade in the U.S. Two January 25, 1928 Brooklyn Daily Eagle articles (here and here) reported on the inventor’s Manhattan demonstration of his namesake instrument in front of a star-studded audience.

Here’s a 1962 demonstration of the Theremin on I’ve Got A Secret. The mysterious machine still needed explaining more than three decades after its invention. Musician Paul Lipman does the honors.

Theremin making music himself.

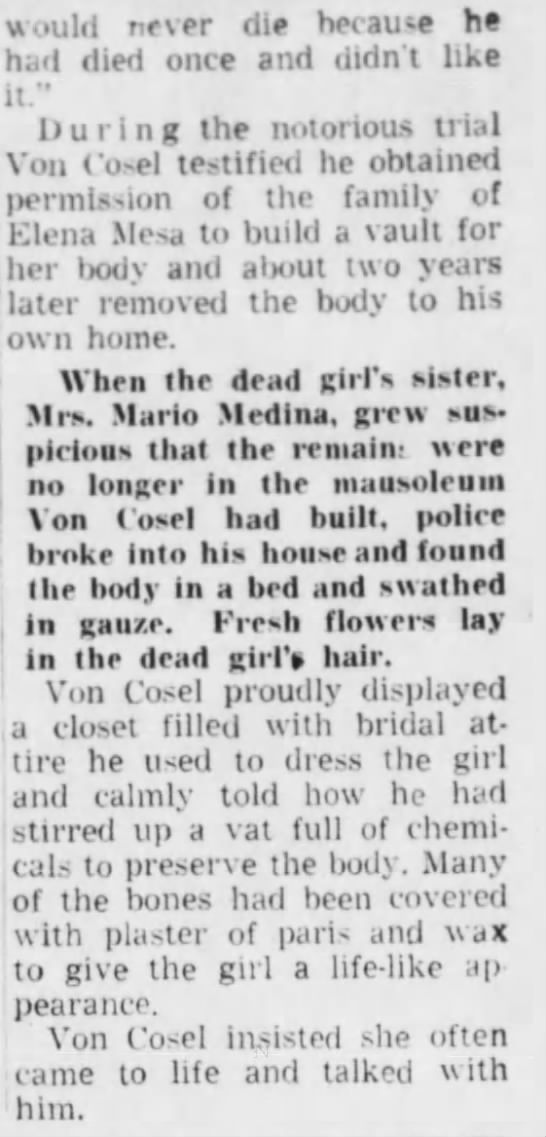

Aga Khan III came from good stock.

Believed to be able to trace his ancestry directly to the prophet Muhammad, the spiritual leader to millions upon millions of Muslims was also a Cambridge-educated, jetsetting, racehorse-owning, tiger-shooting playboy. Considering that many in his flock weren’t exactly ensconced in affluence and he was by all accounts living the highest of high lives, it’s stunning that the Aga Khan inspired not envy but adoration. It was a different time.

A January 19, 1941 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article profiled the Aga Khan when he was 63. It explained the devotion he enjoyed this way: “He works hard for his people and plays hard for himself.” That may have been true, though I can guarantee he didn’t subsist on a diet of peeled grapes as this piece suggests.

Tags: Aga Khan III

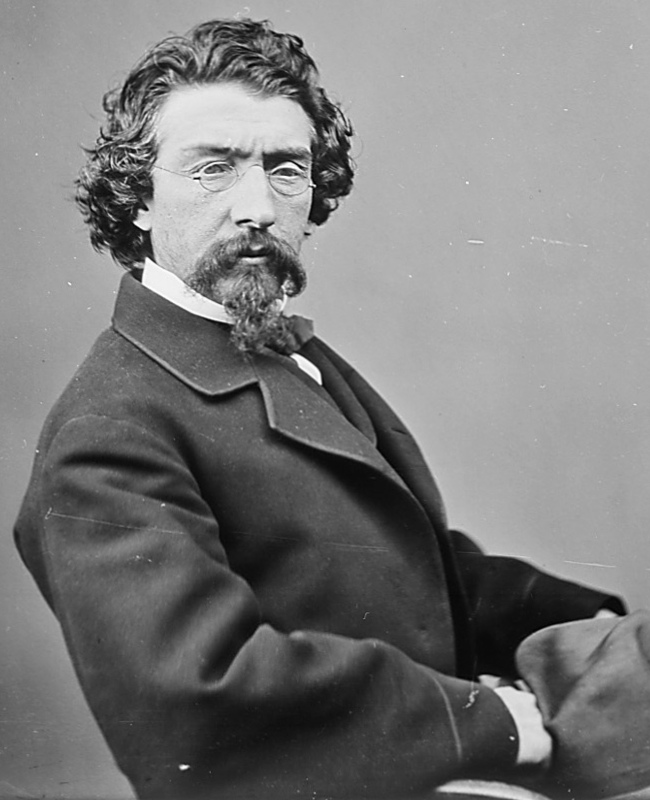

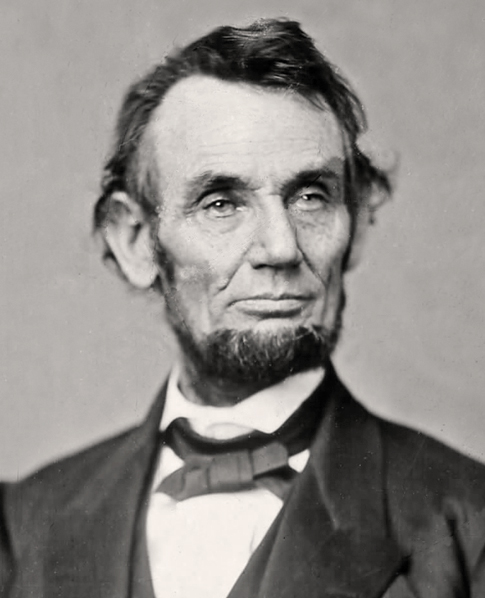

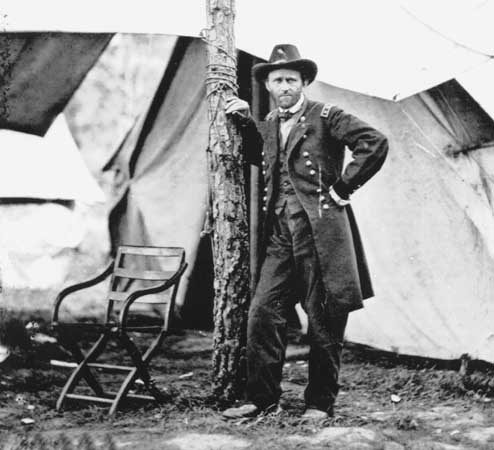

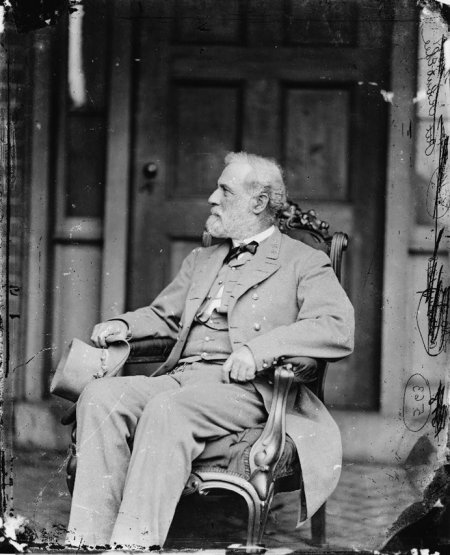

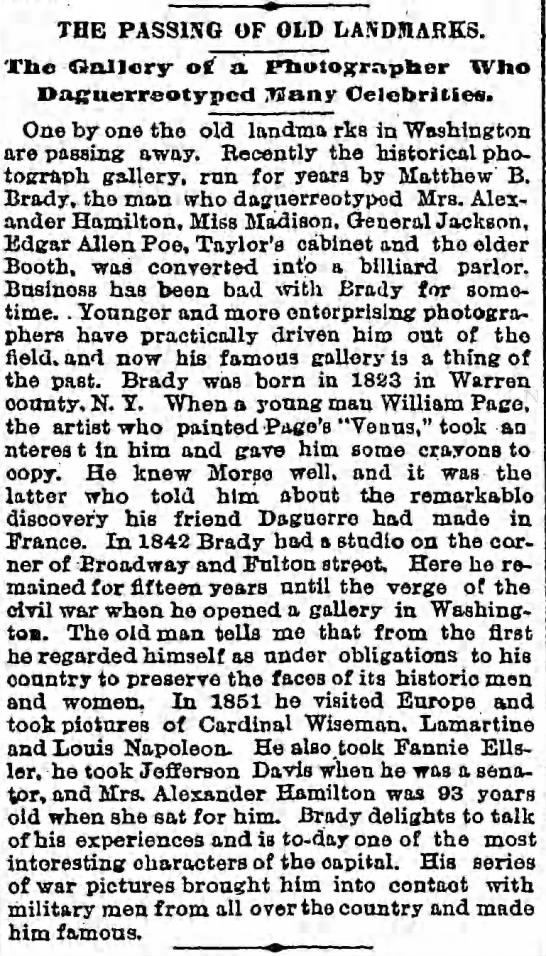

The Civil War would have a name without Mathew Brady but not a face.

Other notable photographers worked in that tumultuous, internecine period, but it was Brady and his pioneering photojournalism that truly captured the visages burdened by the fate of a nation. While Brady was rich in life experience, his relentless attempt to record the Civil War with the expensive daguerreotype process essentially bankrupted him. He expected the U.S. government to eagerly purchase his trove in the post-war period and restore his financial standing, but the money never materialized. Brady died penniless in the charity ward of New York’s Presbyterian Hospital in 1896. Two years before his death, a Brooklyn Daily Eagle article misspelled his first name while chronicling how money troubles cost him his gallery in Washington D.C.

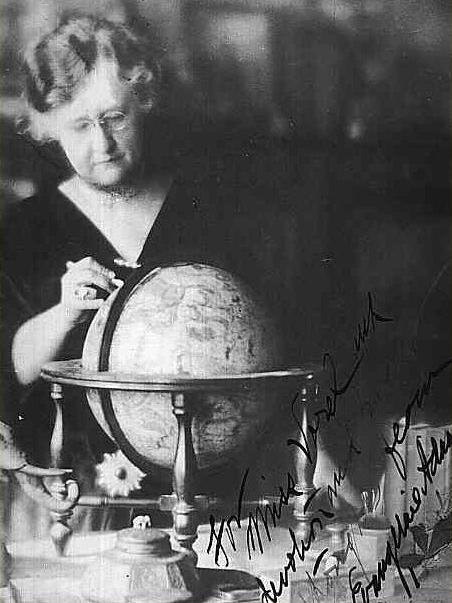

Of all the early 20th-century American astrologers, Evangeline Adams probably did the most to modernize and legitimize the craft, and that’s a shame.

Adams, installed in an apartment above Carnegie Hall at the end of her brilliant career, spent her early years dodging prison sentences for practicing fortune telling before the bullshit was legalized. She differentiated herself from the competition by updating the lexicon for the Industrial Age crowd, sprinkling her predictions with terms like “machines” and “electrical forces.” She was also quite adept at using her powers of persuasion to draw in gullible boldface names (Eugene O’Neill, Tallulah Bankhead, J. Pierpont Morgan, etc.), who gave her a cachet she would not have otherwise enjoyed. But the astrologer’s greatest gift may have been playing the press, aggressively publicizing those occasions she guessed correctly and making her many boneheaded pronouncements go quietly away.

In 1929, she uttered her worst prediction, telling a radio reporter the Dow Jones “could climb to Heaven” just weeks before the bottom fell out. Also interesting is that her most celebrated on-target prognostication, in which she said in 1923 that America would be engaged in a world war in 1942, looks less impressive if you read the fine print. WWII would be provoked, she asserted, when a second American Civil War spread all over the globe. Her 1932 Brooklyn Daily Eagle obituary, embedded below, lauds her “extraordinary record for accuracy.”

Tags: Evangeline Adams

Before media connected us all every second, there was Robert L. Ripley.

The creator of Believe It or Not!–a comic strip in the Hearst papers, then a radio program and finally a T.V. show–traveled the globe beginning in the 1920s in search of oddities and curiosities to entertain and inform Americans, long before travel abroad was something possible for most. His items didn’t exactly go viral–everyone caught them all at once during the Newspaper Age. In Ripley’s own wry way, as a spiritual descendant of P.T. Barnum, he worked to make the world smaller, to establish a Global Village.

As an early King of All Media, he was helped aided in his amateur anthropology and archaeology by his able researcher, Norbert Pearlroth, and helped immensely by his onetime sports editor, Walter St. Denis, who suggested the three-word, exclamatory column title that remains a recognizable phrase even in the Internet Age.

Heart problems ended Ripley’s life young, as recorded in his obituary in the May 28, 1949 Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

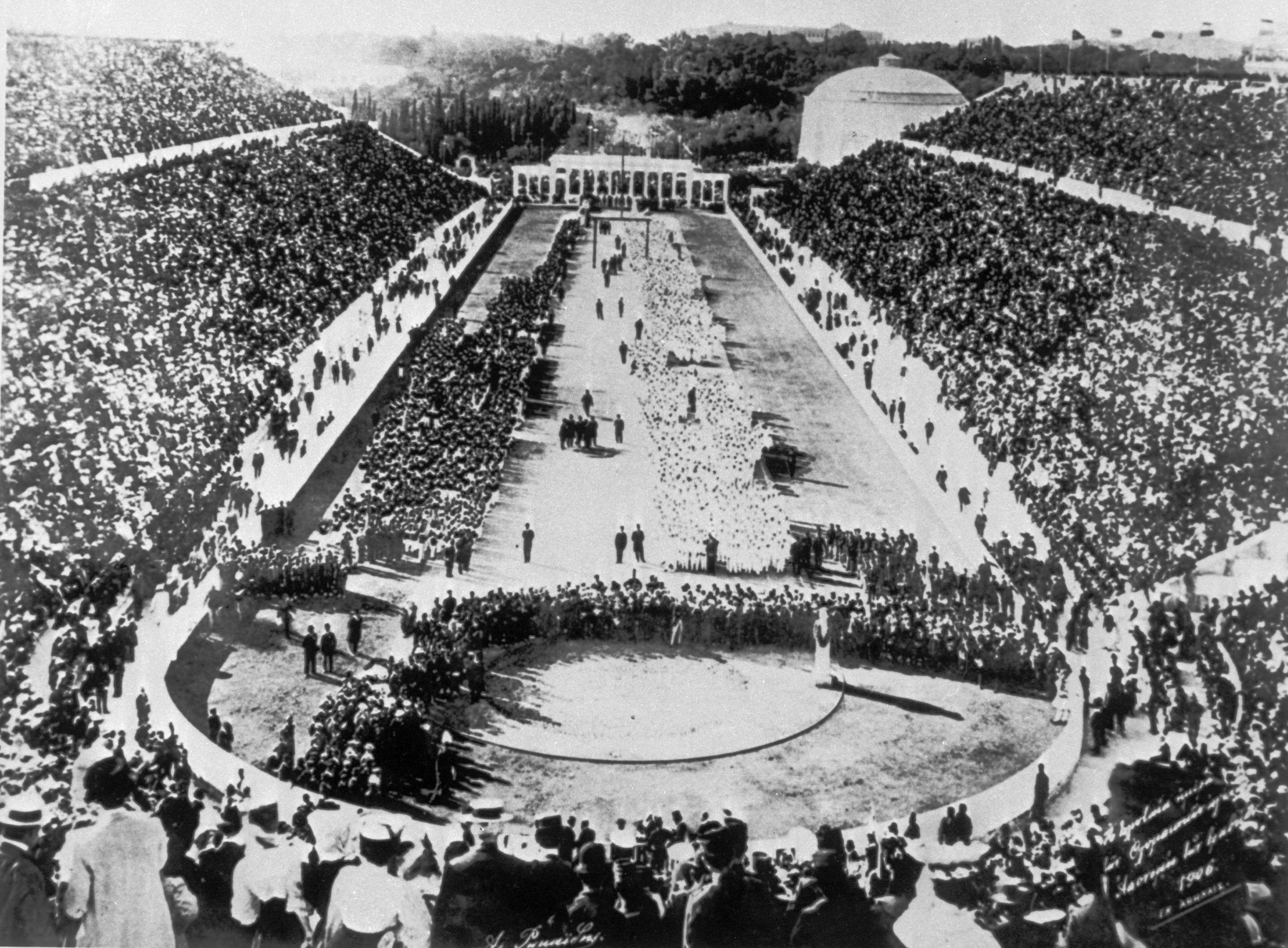

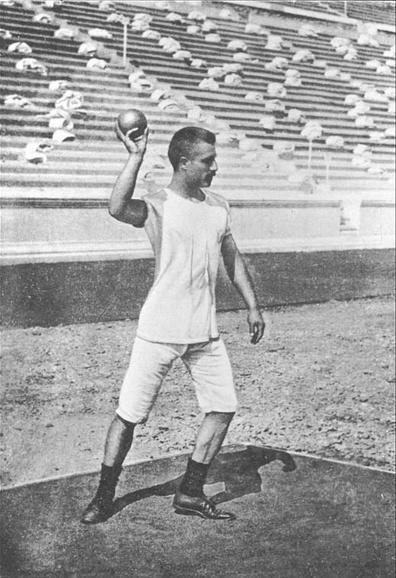

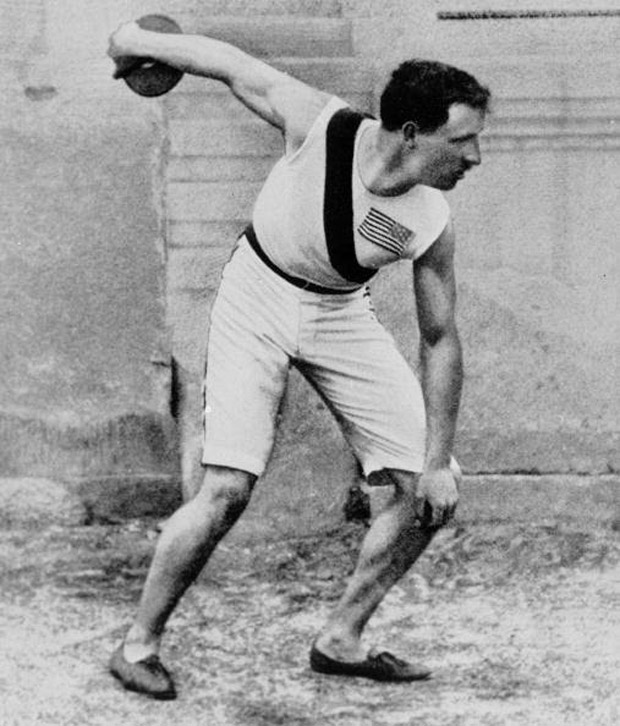

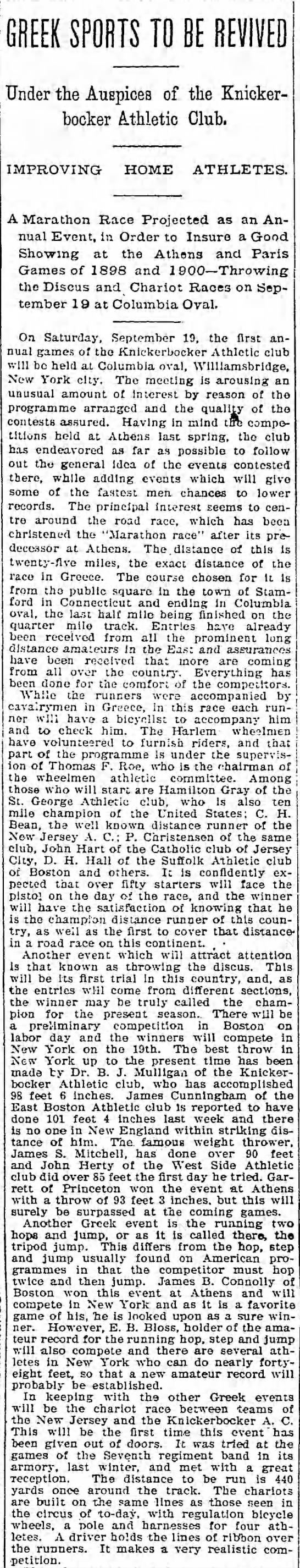

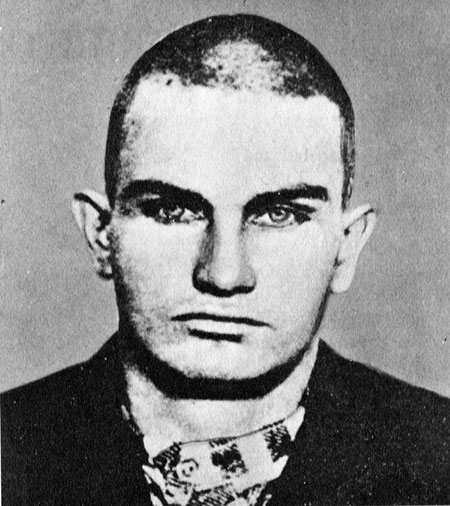

Today is the anniversary of the opening ceremony of the first modern Olympiad, the Athens Summer Games of 1896. While Greece would not host the event again for 108 years, this iteration was paramount for establishing a grandeur, truly globalizing the Games and instituting the Marathon as a major event. Photos above show Panathenaic Stadium, as well as competitors in field events, and unheralded Greek water-carrier Spyridon Louis, who won the Marathon. The particulars of latter event had a surprisingly academic source in French proto-semanticist Michel Bréal, who based its course on the legendary trek run by messenger Phidippides after the Battle of Marathon. Sadly, no women were allowed to participate due to the chauvinism of IOC founder Pierre de Coubertin, but one female still made a mark.

The Olympics sparked interest among American athletes in what had been largely unfamiliar activities, and later that year a collection of U.S. competitors convened in New York City to prepare for future Games. The chariot race was probably not necessary. From a report published in the September 6, 1896 Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

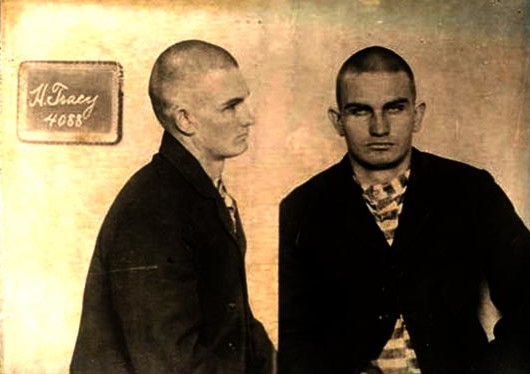

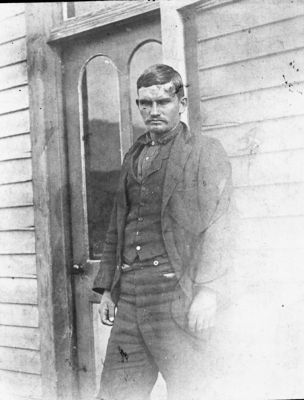

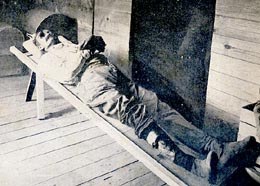

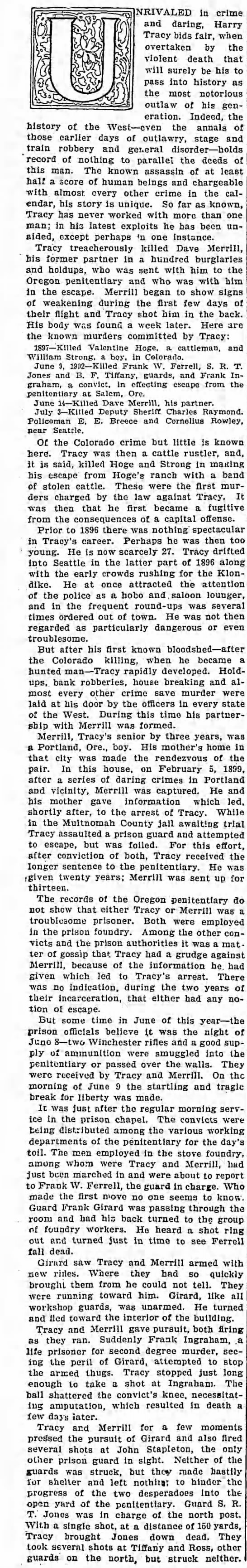

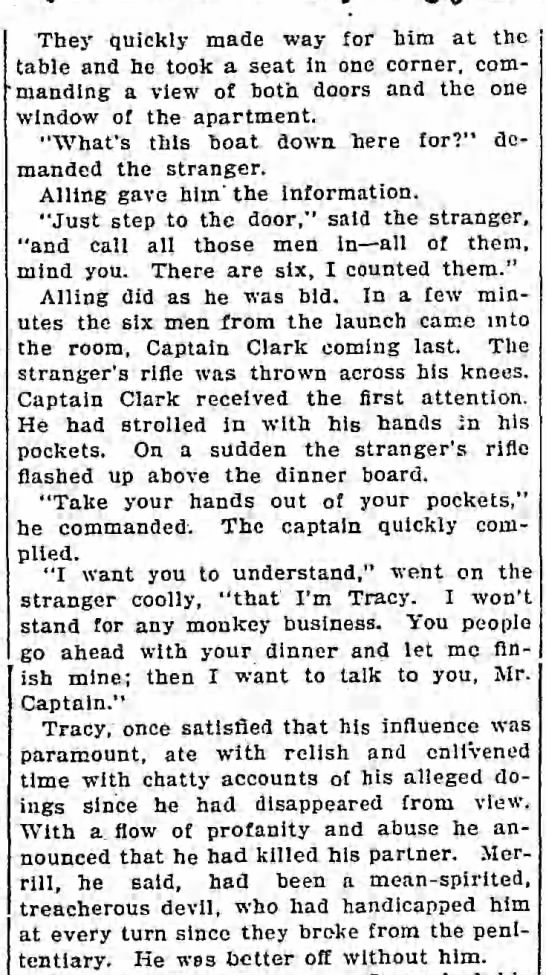

Speaking of law enforcement in pursuit of criminals, the relative low-speed-chase era of the Wild West experienced one of its most infamous prison breaks during its dying days when the outlaw Harry Tracy escaped the Oregon State Penitentiary in 1902, not the first time he’d slipped through bars. The desperado, who had run with Butch Cassidy and the Hole in the Wall Gang, spent nearly two twisty months dodging officers who hunted him while he engaged in a spree of shootouts, kidnappings and ambushes. Ultimately shot in the leg and cornered, he committed suicide to avoid justice at the hands of others. It was his final escape.

While he was in mid-flight, Tracy’s legend was burnished by a very long Brooklyn Daily Eagle article about his life on the lam. The opening follows.

Tags: Harry Tracy

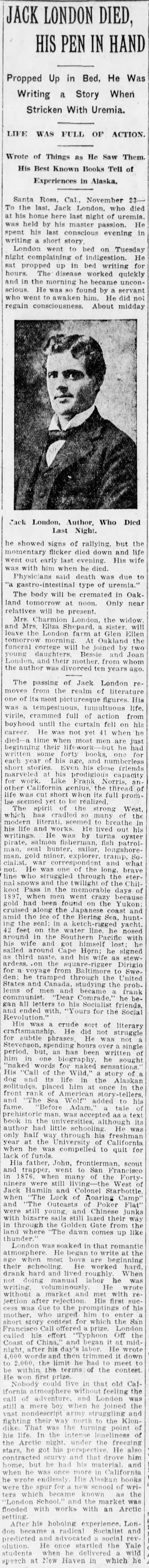

- Jack London had a man’s face when a boy and a boy’s spirit as a man, which probably wasn’t so unusual for a son of California born in 1876. The offspring of a spiritualist and an astrologer, he was a hard-drinking, intrepid adventurer who wrote about masculinity in crude prose and was a template of sorts for Ernest Hemingway, and like most progenitors, he was easily the more authentic item.

- London was not only a writer but also an oyster pirate, salmon fisherman, fish patrolman, seal hunter, sailor, longshoreman, gold miner, explorer, tramp, war correspondent, and, finally, an experimental farmer and rancher.

- I’ve always held a grudge against him for his racism in general, and for the viciousness he particularly aimed at the amazing black heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson.

- Have meant many times to read Iron Heel, his 1908 dystopian novel about the rise of fascism and class warfare in America, and these days I feel especially remiss in not having done so.

- The following article from the November 23, 1916 Brooklyn Daily Eagle announced the writer’s death at 40 from renal failure and more maladies, some self-inflicted and others that invited themselves.

Tags: Jack London