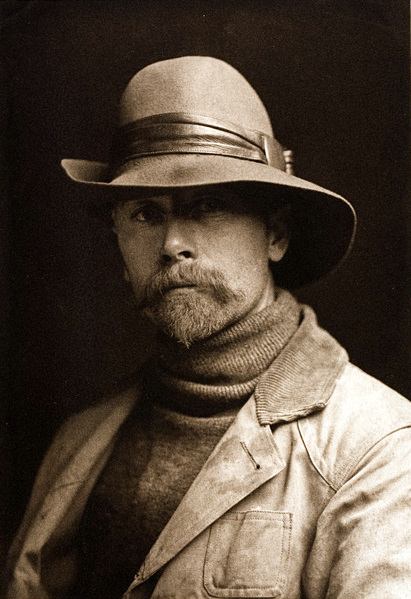

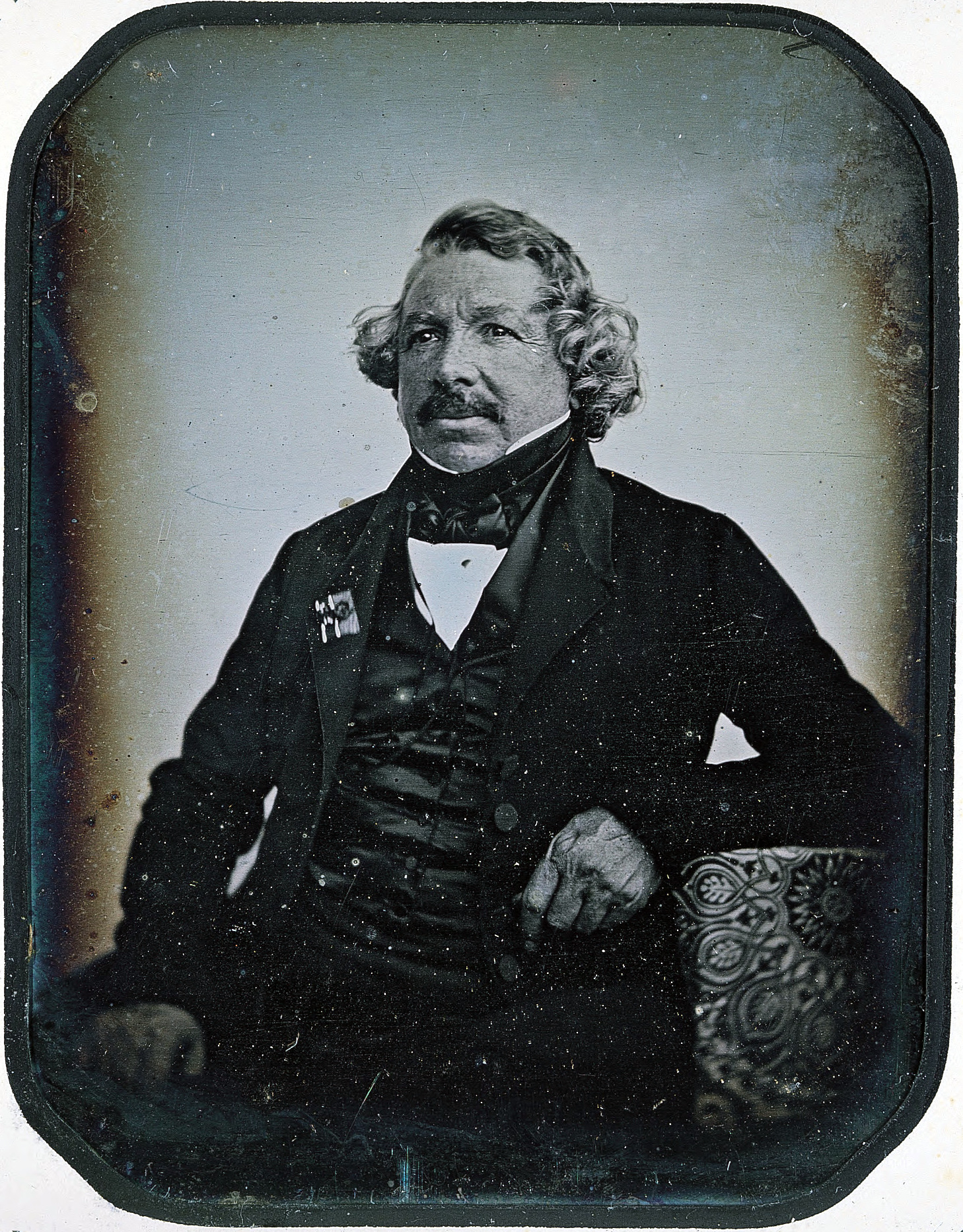

This classic photograph of preacher, politician and fervent abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher was taken at some point between 1855 and 1865 by Mathew Brady’s studio. From an eyewitness account in the New York Times of a speech Ward delivered in Charleston, South Carolina, on April 17, 1865, less than three months after the 13th Amendment outlawed slavery, as countless former slaves who had been sold and sold again tried to reunite with family:

“Feeling was accumulating in the audience, and began to be heard in the low moaning and response, like the sound of the waves upon a distant shore; but when he spoke directly to the blacks before him, of their sufferings in the days gone by, and now of their release; of the loss of their children and of the return of so many, and exhorted them since God had done so much for them to wait with faith and patience for the remainder, and assured them that the morning was on the mountains and the day was at hand, they broke out all over the house in low ejaculations of praise and of thanksgiving. The day was at hand, and they saw it; and the suppressed tone was that of men who could not restrain their joy for the vision. There was no loud shouting, nothing boisterous; it was simply the overflow of deep feeling that could not be restrained. If any of you have open sins, he said, abandon them. If any harbor revenge, rid yourselves of it. I hear good things of you; do better. Mothers in Israel, I expect to hear still more worthy things of you. Fathers, I expect to hear of you counseling better things than ever before. Young men, I expect to hear that you are more virtuous and manly than those that have gone before you.

Many of you old saints will only look over into the promised land, and see it afar off, but your children will enter in. Israel is going to be free. [Cries of ‘Bless de Lord,’ ‘We believe it,’ and one voice near me broke out into a clear hearty laugh of joy.] Intelligence is coming, liberty is coming, virtue is coming.

It is not my joy that this family is down or that one, but this is my joy, that Charleston is free, and every man guiltless of crime can walk her streets unmolested. That our nation marked out for so great things is free. And brethren, consecrate yourselves to the service of Christ, live nobler lives. Bear the cross, it is not for a great white. Some of you are almost down to the river, and it is not half as deep as you think it is. They wait for you on the other shore; you that have showed kindness to the poor white prisoners; you that have borne stripes for it; your reward is waiting you on the further shore.

Sobs and ejaculations of praise swelled through the church.”