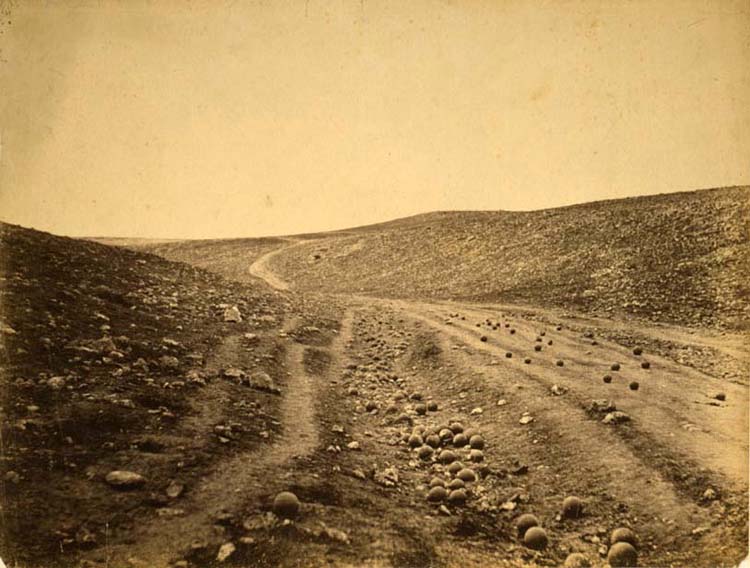

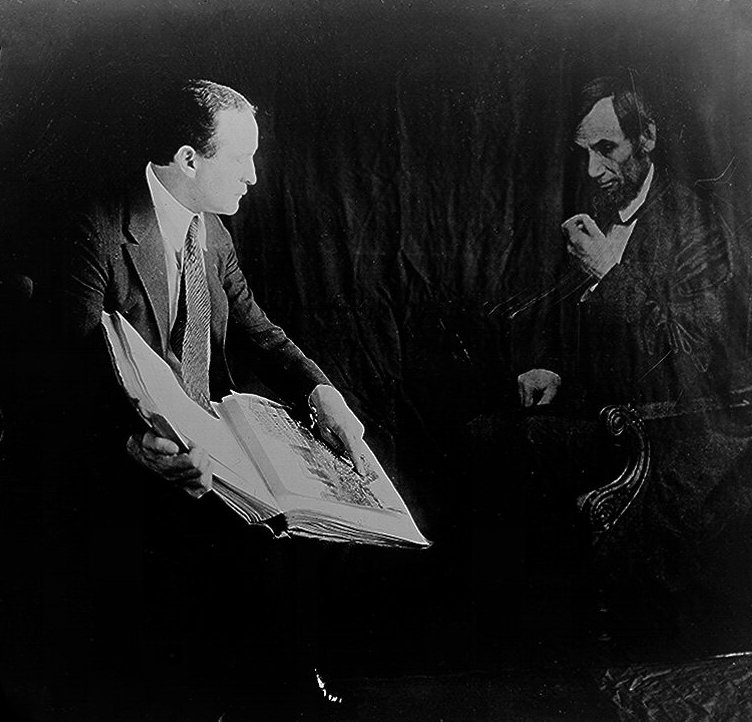

At Public Books, Lawrence Weschler and Errol Morris discuss the latter’s obsession with the meaning of photographs, most recently 1855 pictures of the Crimean War taken by Roger Fenton. An excerpt:

“Errol Morris:

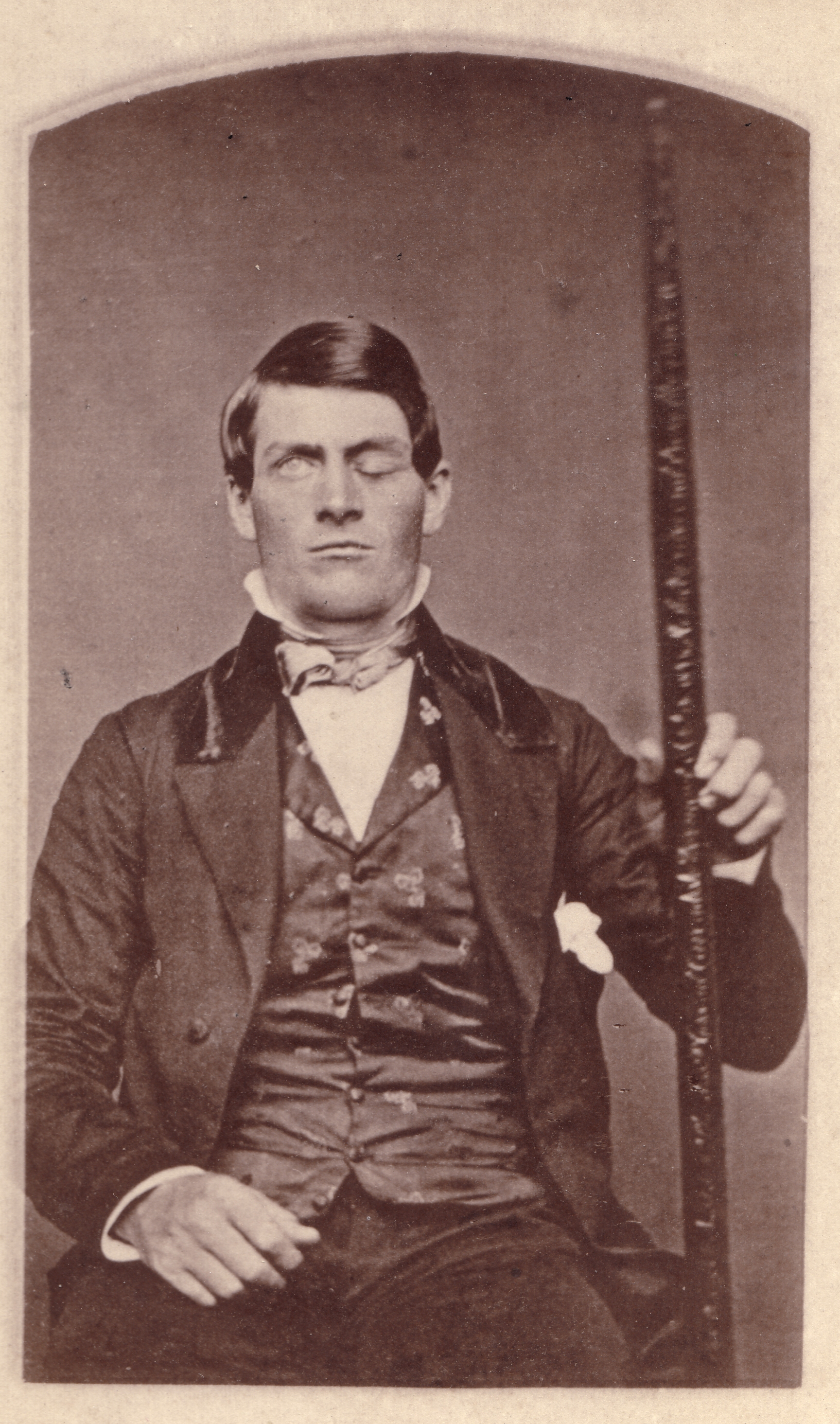

It seems to me that we’ve forgotten a very important fact about photography. That photographs are physically connected to the world. And part of the study of photography has to be recapturing, recovering, that physical connection with the world in which they were taken. Something which has rarely been part of the enterprise of studying photographs. Take a photograph of Einstein, for instance. The point is, it doesn’t matter who I think it’s a photograph of. What matters is, was Einstein in front of the lens of the camera? That man. Was that man in front of the lens of the camera? Is there a physical connection between the image on that photographic plate or the digital device, whatever, and the man standing there? It doesn’t matter what’s in my head. It matters what that physical connection is.

Lawrence Weschler:

What actually happened. But the question remains, why do you care? Or rather, why do you care so much? Because I think you really do care.

Errol Morris:

Ultimately, why do people care about reference? Because… let’s put it this way. If you care what our connection is to the world around us, then you care about basic questions. Questions of truth. Questions of reference. Questions of identity. Basic philosophical questions. So go back to the [Roger] Fenton photographs for a moment. I want to know what I’m looking at. I think photographs have a kind of subversive character. They make us think we know what we’re looking at. I may not know what I’m looking at, even under the best of circumstances here and now. But I have all this context available to me. I know you’re Ren Weschler. I’ve met you before. We actually are friends. And I have this whole context of the world around me. But photographs do something tricky. They decontextualize things. They rip images out of the world and as a result we are free to think whatever we want about them.”